This article is co-published with ProPublica.

In a newly obtained letter sent to Texas authorities, Genene Jones—the former nurse suspected of killing more than a dozen infants—apologized “for the damage I did to all because of my crime.” This marks the first time that Jones, who has maintained her innocence, seems to acknowledge guilt for her alleged crimes.

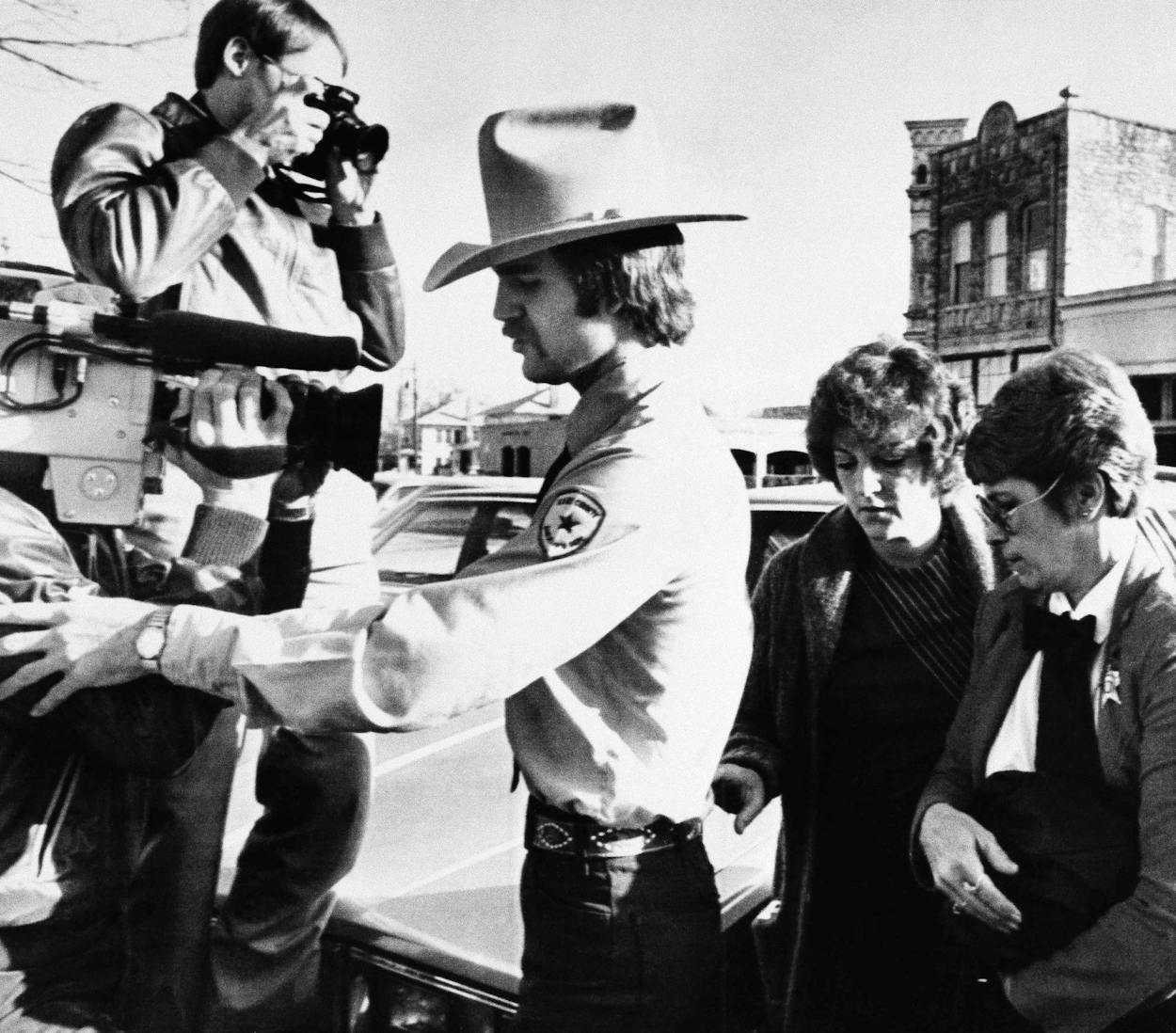

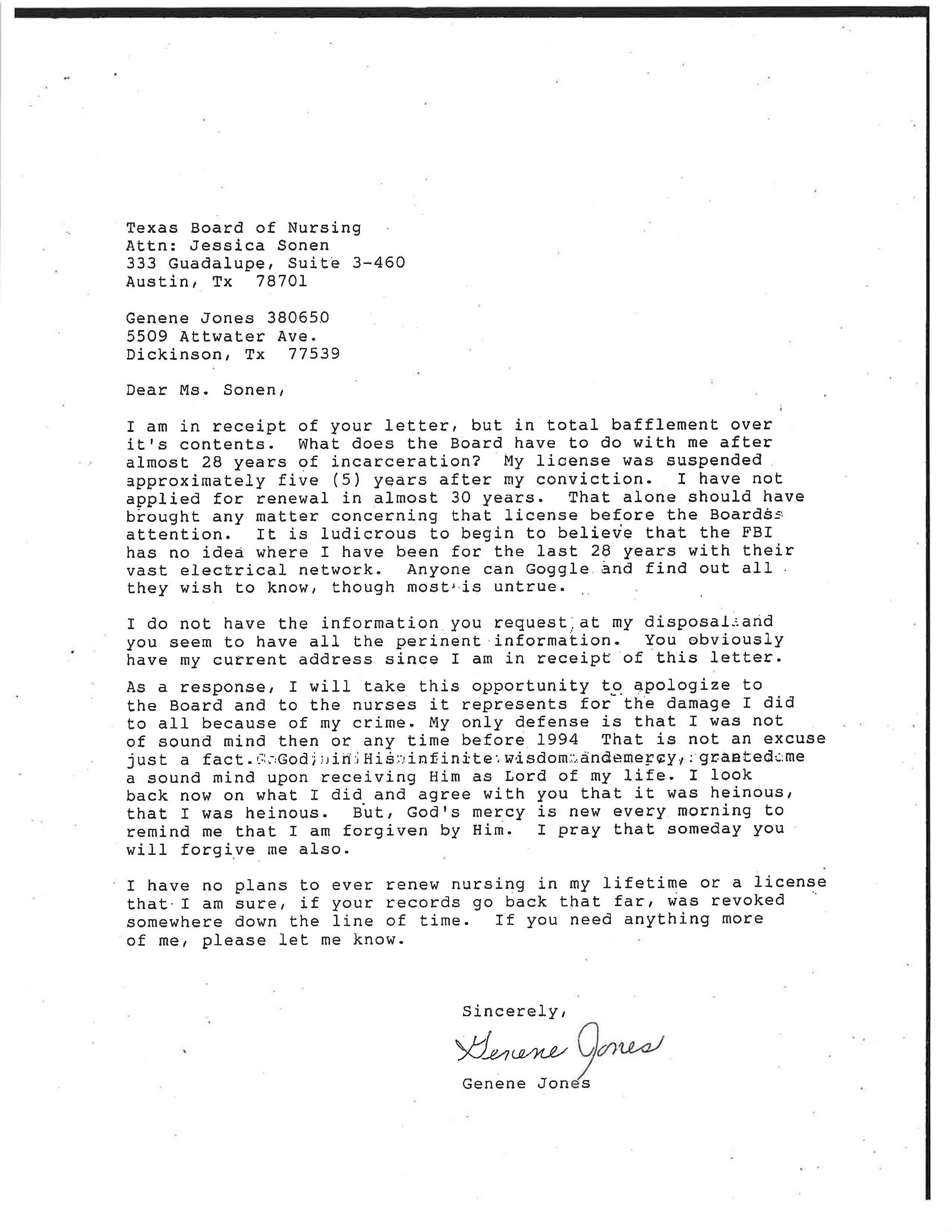

In March 2011, Jones authored a letter to the Texas Board of Nursing from prison. “I look back now on what I did and agree with you now that it was heinous, that I was heinous,” Jones wrote. The letter came as a surprise to prosecutors, who have brought new charges against Jones to prevent her scheduled March 2018 release from prison. Jones, who was convicted in 1984 of murdering a toddler and injuring a month-old baby in 1984, adamantly maintained her innocence during her criminal trials and in two prison interviews in 1987. She has since left standing instructions with prison officials to decline media requests.

“My only defense is that I was not of sound mind then or any time before 1994,” Jones wrote in the letter. “That is not an excuse just a fact. God, in His infinite wisdom and mercy, granted me a sound mind upon receiving Him as Lord of my life.”

The case of Genene Jones, now 66 and once dubbed an “Angel of Death with a needle,” has dramatically resurfaced. Over the past five weeks, a Bexar County grand jury has indicted her for murder in the early 1980s deaths of four children in the pediatric intensive care unit at San Antonio’s county hospital, where she once worked. (Two new murder charges where handed down Thursday.) The indictments resulted from a fresh investigation into more than a dozen suspicious deaths during that period, led by new District Attorney Nicolas “Nico” LaHood.

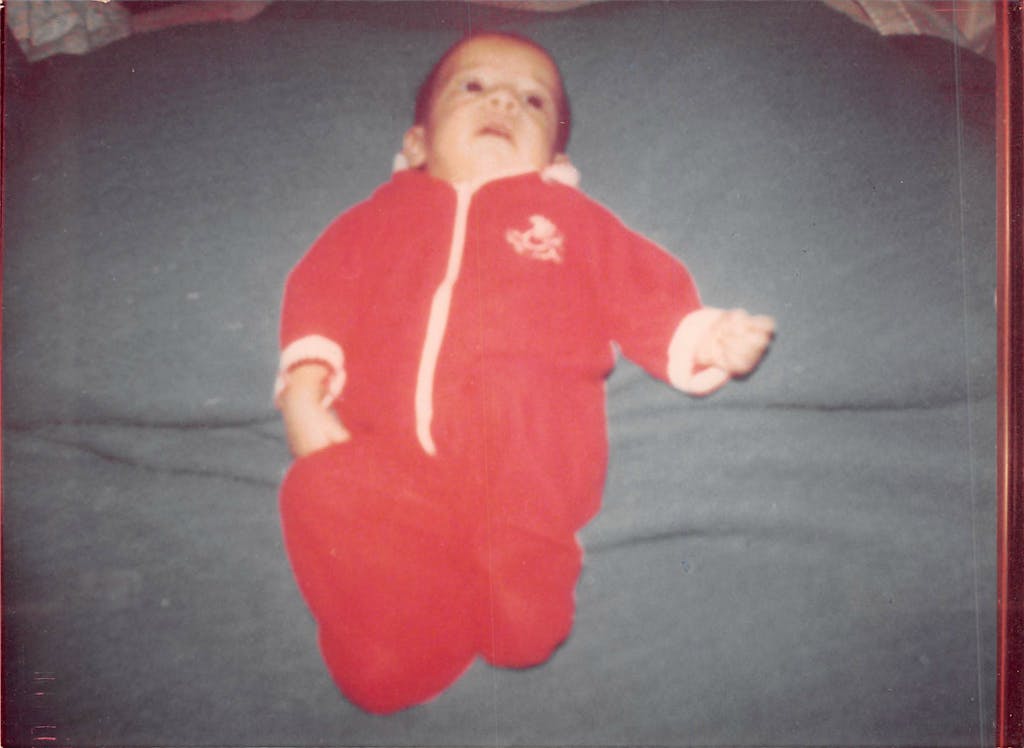

After a jury found her guilty in 1984, Jones was sentenced to serve 99 years for the murder of fifteen-month-old Chelsea McClellan, who died after Jones injected her with a powerful muscle relaxant at a pediatric clinic in Kerrville. Jones had gone to work there after the San Antonio hospital—despite suspicions that she was harming children—sent her off with a good recommendation. Jones later received a second sixty-year sentence, to run concurrently, for nearly killing one-month-old Rolando Santos with repeated overdoses of the blood thinner heparin in the pediatric ICU.

At the time, the Bexar County DA suspected her of involvement in other murders of children but declined to bring charges, reasoning that the cases would be difficult to prove and that Jones’s 99-year sentence guaranteed she’d be spending the rest of her life in prison.

That expectation proved faulty. Thanks to a Texas law aimed at reducing prison overcrowding, Jones is now due to be freed next March, after serving 34 years and eight months.

Responding to a growing public uproar, DA LaHood began bringing new murder charges in late May to prevent her release. Jones will be transferred to Bexar County Jail ahead of March 2018 and held there until trial unless she is able to post the four $1 million appearance bonds set for the new charges.

In the new murder indictments on Thursday, the grand jury accused Jones of killing eight-month-old Ricky Nelson in July 1981 and four-month-old Patrick Zavala in January 1982 by injecting each of the two babies with “a substance unknown.” After learning about Jones’s letter on Wednesday, assistant DA Jason Goss, who leads the DA’s trial team, said he planned to tell the grand jury about it Thursday in addition to presenting testimony from Zavala’s mother.

It is not clear exactly how Jones’s newly disclosed 2011 letter—which was received and quietly filed away—will affect her pending cases at trial. Jones has not yet entered a plea, and she does not explicitly discuss the deaths of any specific children in her letter. But it is not likely to help her defense.

“It’s a confession,” says assistant DA Goss. “That’s a big deal. It’s an incredibly important piece of evidence. We already knew she was guilty. The fact that she’s saying it to this nursing board just strengthens that belief. Just the fact that she’s acknowledging that means she’s not an innocent person in her own mind.”

LaHood, the Bexar DA, said Jones’s profession of faith is not relevant to the question of whether she should face additional charges. “Forgiven and exonerated are two different things,’’ said LaHood, who is himself a vocal Christian. “Can she be forgiven? Absolutely. Should she be exonerated? No. I can forgive her and still want her to take her last breath behind bars. It doesn’t change what we’re going to do.”

Petti McClellan, the mother of the murdered Chelsea McClellan, was similarly unmoved. “It almost makes me angry that she did this but she didn’t apologize to any of us, not just me, but any of the families in San Antonio,’’ she said in an interview. “She must have thought it was going to benefit her. I don’t think there was anything sincere about it.’’

ProPublica and Texas Monthly obtained a copy of Jones’s letter—which was summarized in an order revoking her nursing license—through a Texas public-records request. We first learned about the letter from a Texas registered nurse, who had found the order on the state nursing board’s website after becoming “fascinated” with the Jones story. She then mentioned the letter in a Facebook comment on a post about the latest murder indictment of Jones.

It is, of course, remarkable, that Jones retained her nursing license until 2011. The Board of Vocational Nurse Examiners—which then regulated vocational nurses such as Jones—didn’t even suspend her license until January 1986, nearly two years after her murder conviction. (“If you have, as you say, investigated my case, you are already aware of my innocense [sic],” Jones wrote in protest before the decision.) Jones lost her criminal appeal that August. Yet no further regulatory action followed over the next 25 years.

The Texas prison system also struggled to make sense of Jones’ status as a nurse. In August 1984, a state prison official wrote to the Bexar County Hospital District to ask if there was any problem with inmate Jones being assigned to work in the prison hospital’s dispensary. After word of the inquiry leaked out, a prison spokesman offered a public assurance that the state would find Jones work that had nothing to do with medicine.

In February 2011, a Huffington Post story about the prospect of Jones’s future release prompted Texas’ Board of Nursing, which now regulates all state nurses, to revisit the issue and initiate revocation proceedings, says board general counsel James “Dusty” Johnston. The goal, says Johnston, was “just basically putting closure to the matter.”

Notice of this proposed action went out on March 18, 2011, to Jones, then in a prison-system medical facility in South Texas, where she was being treated for health issues. In an undated four-paragraph reply the board received on April 1 of that year, Jones expressed “total bafflement” that her nursing license remained an open issue.

“What does the Board have to do with me after almost 28 years of incarceration?” she wrote. “My license was suspended…after my conviction. I have not applied for renewal in almost 30 years.’’ Anyone can search the internet “and find out all they wish to know, though most is untrue.” Jones then went on to offer what amounts to an unsolicited confession:

As a response, I will take this opportunity to apologize to the Board and to the nurses it represents for the damage I did to all because of my crime. My only defense is that I was not of sound mind then or any time before 1994. That is not an excuse just a fact. God, in His infinite wisdom and mercy, granted me a sound mind upon receiving Him as Lord of my life. I look back now on what I did and agree with you that it was heinous, that I was heinous. But, God’s mercy is new every morning to remind me that I am forgiven by Him. I pray that someday you will forgive me also.

I have no plans to ever renew nursing in my lifetime or a license that I am sure, if your records go back that far, was revoked somewhere down the line of time. If you need anything more of me, please let me know.”

Sincerely,

Genene Jones

The board finally revoked Jones’s license to practice nursing on June 10, 2011.

Though separated by decades, Jones’s letter was entirely at odds with her long-held insistence about her innocence. She pled not guilty at both her trials in 1984. In the days after her first conviction, for the McClellan murder, Jones, who had declined to testify, spoke to reporters for hours and happily posed for photographs. “I’m not afraid of jail, because I’m innocent,” she declared. “If I had to spend ninety-nine years in solitary, I could live with myself because I didn’t do anything.”

Prior to the 2011 letter, Jones’s most recent public statements came during two conversations I had with her in 1987 at the state prison in Gatesville for a book I wrote about the case.

Furiously combative while working as a nurse and during earlier interviews, Jones had mellowed considerably by then. The four-letter epithets that once salted her conversation were gone. Once quick to rage, Jones now seemed placid and relaxed, even gentle. She attributed the change to a newfound religious faith. “I’ve been given time to sit down and understand the Lord,” she told me. Jones had replaced the cross she wore on a chain around her neck during her murder trial with a Star of David. “I’m leaning toward the Jewish religion,” she explained.

Yet Jones, in 1987, remained adamant that she’d been railroaded. “The story of my conviction is about big money,” she declared, railing about how much the state had spent to put her behind bars. I finally asked her directly: Did she still believe she bore no personal responsibility—no blame for what had happened?

“That’s not a belief,” Jones insisted. “That’s a definite fact. I know I am responsible in a way for bringing it to the public viewpoint, but as far as being responsible for any death—no, I am not.”

So I asked her another way: Did she think she could perhaps be the victim of a disease of the mind that led her to harm children without her conscious knowledge? “No, I don’t,” she replied immediately. “Not at all. I’ve had a lot of time to think. I don’t have any doubts in my innocence.”

Peter Elkind is a former Texas Monthly staff writer and the author of The Death Shift: Nurse Genene Jones and the Texas Baby Murders.