This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

When I first decided to handicap the upcoming primary elections, I went searching for the archetypal ordinary voter to get a reading of early popular sentiment. I found a likely subject in a barbecue emporium in Luling, munching on some ribs doused with a mustard sauce. I handed him a list of names of people running for statewide office and asked for his reactions. He’d heard of Dolph Briscoe, he knew about John Hill—“the doc who did his wife in and then got shot up, right?”—he was a little surprised ol’ Warren G. Harding was still around, and he was pretty sure Reagan Brown had taught his daughter back in the third grade. The rest he’d never heard of.

Such voters have always made up a substantial part of the Texas electorate. Though they usually frequent the aging Main Streets of East Texas market towns and the dusty courthouse squares of West Texas, they can be found in the big cities as well, many of them just a generation removed from the soil. Like Thomas Jefferson, they regard the small farmer as the embodiment of democracy’s perfect citizen. All they have ever wanted from state government is good roads and teachers for their children and, occasionally, protection from banks, railroads, liberals, and other predators. These are the people who elected Ma and Pa Ferguson, Pappy O’Daniel—and Dolph Briscoe.

But there is another side to the Texas electorate. The continuing theme of Texas politics for the last century has not been a battle between conservatives and liberals—that’s of comparatively recent vintage—but a fight between agriculture and business. Industrial/commercial Texas, despite the mythology of laissez-faire, has no desire for government merely to leave it alone. The state’s vast underground treasures could never have been tapped without appropriate laws obligingly passed by the Legislature. The state’s eleven ports might never have prospered without friendly legislation letting them purchase state-owned coastal lands for $1 an acre. Perhaps Texas might not be the home of so many insurance companies if rates weren’t set (and profits guaranteed) by state laws and gubernatorial appointments.

Traditionally farmers have feared government more than businessmen, partly because the latter have been in control more often and partly because the farmer seldom thought about the government unless times were hard. Though Texas has produced governors like Jim Hogg, who in the 1890s chased forty insurance companies and a Standard Oil subsidiary out of the state, it has also produced friends of business like William P. Hobby, Dan Moody, Allan Shivers, and John Connally. And so it has gone through the years, one side calling for less governmental activity, the other more.

The 1978 Briscoe-Hill governor’s race between a rancher from Uvalde and a lawyer from Houston heralds a return to the old battle lines of Texas politics. The liberal-conservative feud that has dominated Democrats since 1944 is hardly a factor in the 1978 elections; the rift has not healed so much as it has been passed by. The old issues don’t matter anymore. The three rallying points of Texas liberalism have been civil rights (the issue that caused the original split in 1944); bettering the lot of the working man; and protesting the cozy relationship between business and government, covering everything from regressive taxation to state agencies that befriend rather than regulate. Today civil rights as an issue is dead, and the new ethnic issues are part of much larger problems, like illegal aliens and the decline of the central cities. Meanwhile minority politicians have contributed to the demise of the old liberalism by being interested chiefly in getting their share of the pie—and pragmatic conservatives are better positioned to do the slicing. Improving the lot of the working man has come to mean more power for organized labor, something the majority of Texans philosophically abhor. Even the putative relationship between government and business seems a little more bearable as it becomes increasingly clear that the Texas economy is (1) the envy of Northern states and (2) the target of same. Instead of the old issues, the 1978 campaign is likely to turn on the way voters perceive the state of the state. Are they satisfied that times are good and taxes low? Or are they uneasy over the energy bill, the waning of Texas’ influence in Congress, the future?

The following capsule evaluations of the major state races (Railroad Commission Chairman Mack Wallace and Lieutenant Governor Bill Hobby have only token opposition, and Comptroller Bob Bullock and Land Commissioner Bob Armstrong are unopposed) were compiled after many discussions with candidates, campaign managers, local politicians, newsmen, lobbyists, and ubiquitous “political observers” around the state. Like the betting line for a football game, the odds representing percentage of the vote reflect the way things are starting out, not necessarily the way they’re going to end up. The campaigns haven’t really gotten the voters’ attention yet; poll after poll shows Undecided leading. (It figures. Seems like he’s been running things for years.) Whichever way the balance tips on May 6, the struggle between agriculture and business, country and city, is likely to go on unresolved, as it has for a century.

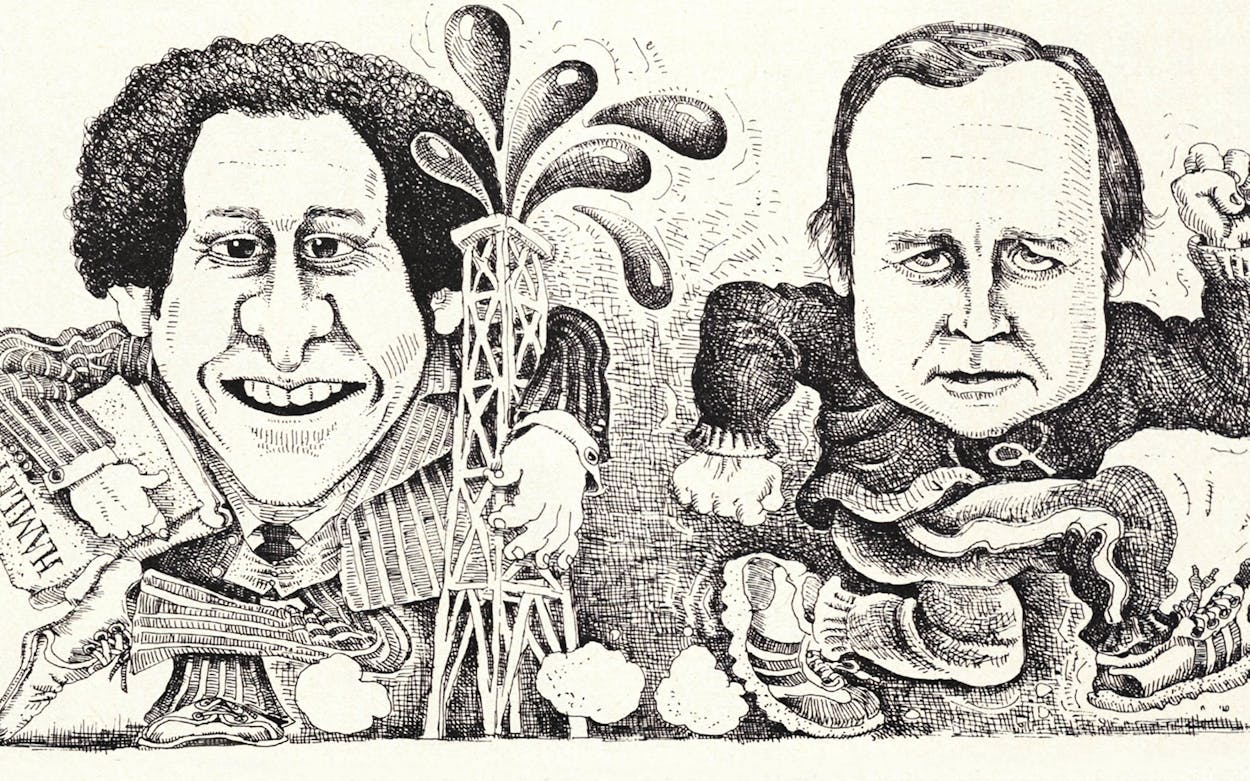

Governor: Democrat

This is the Super Bowl of the political season, the race with the most attention, the most money, and the biggest stakes. As if that weren’t enough, the battle between Dolph Briscoe and John Hill (former governor Preston Smith is in the race too) is potentially a political watershed: one of those races that occurs once in a generation where all the traditional rules of Texas electoral politics are put to the test to see if they are still valid.

Texas voters, for example, are supposed to want as few reminders of their state government as possible, and Briscoe has certainly obliged them. He has spent much of his term at his Uvalde ranch, something that has earned him scorn in Austin and praise elsewhere. Except for a law-and-order package that was mostly show and the controversial $528 million highway bill passed by the 1977 Legislature, the average Texan can rest easy that Briscoe’s personal program has been virtually nil—except, of course, for his much-publicized promise of no new taxes. True, he’s had the benefit of inflation and the energy crisis, which have helped fill tax coffers beyond the wildest estimates of the early seventies; and yes, during Briscoe’s tenure the state has embarked on an unprecedented spending binge. But none of that seems to worry anyone very much, even fiscal conservatives. “At least we’re living within our income,” says an old-line Austin lobbyist and power broker; and a well-connected Houston lawyer says, “Sure Briscoe’s been lucky. And I don t go around throwing away good luck charms.”

Hill, in addition to running against an incumbent, is bucking the odds in other ways. Even though more and more of the vote is urban these days, the key to winning elections has always been in the countryside, where people talk politics, turn out in large numbers, and tend to think alike. Jimmy Carter carried Texas by winning the rural vote; Lloyd Bentsen swept to his 1970 senatorial victory over George Bush on the strength of a 174,000-vote margin mostly from counties with less than 50,000 people. Unlike New York or Illinois, which have one huge city that is overwhelmingly liberal and Democratic, Texas has several urban centers that are politically diverse and often cancel each other out, leaving the race up for grabs in the outlands. And that is Briscoe country. To add to Hill’s woes, the standard view of how to beat a conservative governor—sweep the liberals and win the fight for the center—cannot offer the challenger much comfort. Despite all the inside jokes about Briscoe’s incompetence, he is politically more astute and more flexible than most Texas politicians: it is true that he once appointed a dead man to a minor office, but it is also true that he’s appointed Mexican American judges, a black to the Texas A&M Board of Regents, and a number of people friendly to organized labor. He will get substantial liberal support, primarily from labor on the Gulf Coast and Mexican Americans in South Texas.

Hill has other handicaps as well: he has less money (Briscoe raised as much during one party at his Sabinal Ranch—$1 million—as Hill will spend during the entire campaign), and is something less than the quintessential media candidate. Yet, contrary to the conventional wisdom, Hill is very much alive in this race. He compiled an outstanding record as attorney general, winning major courtroom victories in the Howard Hughes will contest and against Houston Ship Channel polluters and Southwestern Bell. A lot of voters are not comfortable with the thought that Briscoe, if reelected, will end up as governor for ten years, longer than anyone in Texas history. The mini-scandal in the Governor’s Office of Migrant Affairs has probably been overplayed—the questionable use of poverty program funds is a nationwide problem—but voters are beginning to make a connection between Briscoe’s absenteeism, the peculiar things happening in his office, and his longevity. Briscoe has done nothing to defuse the longevity issue with a series of appointments from Uvalde and from his personal staff.

Briscoe is also suffering from his mediocre record as governor. Seldom during his three terms has he exercised any leadership with the Legislature. Briscoe has been worthless as a spokesman for the state during the critical national energy debate, and it must have occurred to striking farmers that he is unlikely to be more successful on their behalf. Until Briscoe, Texas politicians have never been so hidebound by philosophy that they’ve ignored the benefits of dealing with the rest of the country: defense contracts, depletion, dams, NASA, and more. During Briscoe’s tenure Texas has lost a superport and is losing the energy battle. So while some conservatives are convinced that the state can’t afford to lose Briscoe, others are equally certain we can’t afford to keep him.

In many ways the election is a referendum on the degree of sophistication of Texas politics: are voters ready for the activist governor Hill would surely be, or is Briscoe really what they want? It is going to be close; much depends on the effectiveness of Hill’s closing media campaign, and on how many—and whose—votes Preston Smith will siphon off. Not since Shivers beat Ralph Yarborough in 1954 has an incumbent governor been forced into a runoff, and only four incumbents have been defeated in this century, including, of course, Smith. This will be a landmark race in Texas politics, one the pros will study for years, but in the end Hill may be a few years too early. Briscoe by 1.

Senator

It doesn’t seem fair that the two best candidates on the Democratic ballot should be running against each other. Bob Krueger and Joe Christie are both smart, likable, honest, effective, and independent. Either would undoubtedly make a good United States Senator. But one will be eliminated in the primary, while the other will start out as a substantial underdog against John Tower.

Krueger, 42, is the brightest newcomer to Texas politics, a Shakespearean scholar with a PhD from Oxford who left academia to come home to New Braunfels and run for Congress in 1974. Given little chance at the start, he surprised everyone by rolling up strong margins in the rural areas of the sprawling district that stretches from San Antonio to San Angelo. By the end of his first term he was everyone’s choice as Rookie of the Year on Capitol Hill for his efforts to deregulate natural gas.

Christie was a solid state senator from El Paso who lost a race for lieutenant governor in 1972 to Bill Hobby. Rescued from obscurity by Dolph Briscoe, who appointed him chairman of the State Board of Insurance, Christie changed the SBI from an agency beholden to the insurance industry to one tilted toward the consumer. It is a tribute to Christie’s political skill that he retired on good terms with most of the industry.

A year ago when Christie, Krueger, and a host of others were mentioned as possible Senate candidates, Christie was better known than Krueger and would surely have won a head-to-head race. But while Christie debated whether to run, Krueger made up his mind early and started drawing money, commitments, and staff. Joe Bernal, a state Senate colleague of Christie’s and an influential figure on San Antonio’s Mexican American West Side, committed to Krueger; Bernal has since landed a federal appointment (with Krueger’s help) and is out of the campaign picture, but similar things happened all over Texas. It seems absurd that Christie’s announcement seven months before the election could be too late, but it was. If Krueger has not yet built himself into a formidable candidate, he has certainly thwarted Christie’s effort to do likewise. The danger of starting too soon is that you peak too early, but rather than build him up publicly, Krueger worked behind the scenes to cut off Christie’s money and support.

Krueger’s edge hasn’t really shown up in the early polls, which are inconclusive, but his head start in money and organization will begin to tell as the race enters the stretch. The problem facing Christie is that the average voter finds it hard to distinguish between two attractive, moderate candidates. The only real difference between them is one of style: Christie is a hail-fellow-well-met; Krueger hasn’t a shred of good old boy in him and doesn’t try to hide his intellect. A lot of local politicians are more comfortable with Christie; they think Krueger is a phony, because they’ve never seen anybody like him in politics. But ordinary voters seldom react that way. Krueger has mastered the art of making his sophistication appealing.

Christie has been running a textbook campaign, but it’s an outdated textbook. Instead of buttonholing contributors, he’s crisscrossing the state, seeing people from dawn to midnight in clusters of twenty or forty people. Texas is too big for that nowadays; the only ways to make up for lost time, short of catastrophic mistakes by the opposition (not a Krueger hallmark), are money or a catchy issue. Most political pros say that if Christie could match Krueger’s war chest he could beat him, because, they believe, Christie’s relaxed style is more in tune with the Texas voter than Krueger’s high-brow approach—but it takes money to get that message across on TV. The premise is a questionable one at best—John Tower’s polish has served him well for years—but it is unlikely to be tested. Christie is having a terrible time raising money.

As for an issue, the only one available is Krueger’s close identification with the oil and gas industry. Here too Christie has failed to put any distance between himself and Krueger. He says he would have voted for the Bentsen deregulation bill instead of the Krueger bill. So what? That could get him Lloyd Bentsen’s vote, but who else’s? It might seem risky to run against the petroleum industry in Texas, but more people pay utility bills than receive royalty checks; in any event, when you’re behind, you have to take risks. With half the electorate still undecided, Christie is not so far behind he can’t catch up, but unless he alters his tactics the candidate ahead now will stay ahead. Krueger by 6.

Attorney General

Through the years few Texas politicians have advanced their careers by running against people named Price Daniel. The only one who comes to mind is none other than John Connally, who thwarted Price, Sr.’s bid for a fourth gubernatorial term back in 1962—aided by Daniel’s reluctant acceptance of the state’s first sales tax a year earlier. Now it’s Price, Jr.’s turn. Only 36, he has already been a state representative, Speaker of the House, leader of the post-Sharpstown reform movement, and President of the 1974 Constitutional Convention. Even though not all reviews of his performances have been raves—he is known as “Half-Price” to his detractors—few doubt that he’s destined to be Texas’ next attorney general.

One of the dissenters, of course, is Mark White, Dolph Briscoe’s secretary of state from 1973 to 1977 and Daniel’s opponent. The race hasn’t generated much interest in the early going—mainly because White hasn’t generated much action—but many old political hands believe this is the most important race on the ballot. “I’d damned sure rather see Mark White attorney general than Dolph Briscoe governor, if I had to choose one,” says an influential business lobbyist. “We’ve got to stop Mark White here and now, or we’ll be plagued by him for years,” says Billie Carr, majordomo of Houston liberals and a national Democratic committeewoman.

Though Texas Democrats are notorious for acrimonious infighting, this is the only race on the ballot this year reminiscent of the liberal-conservative ideological struggles of years past. Daniel is not a classic national Democratic liberal, but he is a reformer, a successful reformer at that, and that’s enough to make him anathema to much of the Texas political establishment. White, on the other hand, while not an establishment conservative in the John Connally mold, is a genuine philosophical conservative—the sort of person who believes that voting should be regarded as a privilege. Indeed, as the state’s chief elections officer he did his best to undo the state’s liberal permanent voter registration system (only to be rebuffed by the federal courts), carried the fight against single-member districts to the Supreme Court of the United States (unsuccessfully), and bitterly opposed the extension of the Voting Rights Act to Texas (also unsuccessfully).

An active attorney general can wage war on polluters, vigorously uphold the rights of consumers, and keep cities and state agencies in line through tough interpretations of open-records laws. Daniel would undoubtedly follow in John Hill’s footsteps as an aggressive attorney general; White would be more like Hill’s predecessor, Crawford Martin. Daniel, for example, enthusiastically endorses allowing consumers to collect triple damages for fraud; White, while saying he would enforce the law as written, has indicated so little enthusiasm for triple damages that several Austin-based lobby groups are supporting him in hopes he’ll cooperate with legislative efforts to repeal the law.

If the Austin political community were the only ones voting in the race, White would be a strong favorite. Daniel has a bad reputation for not shooting straight with fellow politicians—and a worse reputation for not admitting it. “I don’t like getting lied to,” says one former legislator who claims Daniel violated an ironclad promise, “but I can’t stand getting lied to about getting lied to.” Daniel got crosswise with labor during the 1974 Constitutional Convention by reneging on a long-standing pledge not to let a right-to-work provision into the proposed constitution; then when his compromise failed to pass, Daniel lambasted his former labor allies for contributing to its defeat. Four years later labor leaders are still so furious that White actually has a chance to get the labor endorsement.

Lobbyists also have no love for Daniel, who led the fight for reform of financial disclosure and campaign contribution laws, so White should be able to raise big money from Austin-based trade associations. But surprisingly Daniel was raising more money in the early going—a sure sign that conservatively oriented contributors are following the advice of their heads rather than their hearts. Even White’s supporters in Houston and Dallas concede that Daniel is far ahead in support, name identification, and organization. Daniel may well be the most widely disliked person in Texas politics, but as one White supporter lamented, “Everybody who knows Daniel is against him and everybody who doesn’t know him is for him—and there are a whole lot more people in this state who don’t know him.” Daniel by 14.

Governor: Republican

The Republicans have their own version of political football: Bill Clements in the air against Ray Hutchison on the ground. Clements, a Dallas millionaire industrialist and Deputy Secretary of Defense in the Nixon and Ford administrations, will be spending up to $500,000—an unheard-of sum for a Republican primary—as part of a massive TV and direct mail campaign to get his message across. And the money is the message. Three times in the last decade—Paul Eggers in 1968 and 1970, Hank Grover in 1972—Republicans have made serious runs at the governorship, only to fade in the stretch when money ran short. That won’t happen to Clements—if he gets that far.

If this were a Democratic race, where the problem is penetrating a vast electorate, Clements’ money might even make him the favorite. Fortunately for Hutchison, a Dallas lawyer who can’t come close to matching Clements dollar-for-dollar, Republican politics are different. Despite the GOP’s image as a silk-stocking aggregation that holds party meetings at the local country club, the party’s strength—and Hutchison’s—lies in the middle class. For the last four years, while Clements was off in Washington, Hutchison has built a following among the party’s rank and file. After serving two terms in the Legislature (where he was the consensus choice as the best member of the House), he stepped down—or up—to become state Republican party chairman. He has spent the last two years carefully tending the grass roots; he knows the precinct chairmen and party workers who make the difference in Republican elections. Not all grassroots Republicans are fond of Hutchison; some see him as a country club Republican, too, and many Houstonians haven’t forgotten that he backed Gerald Ford against Ronald Reagan and defeated Reaganite Ray Barnhart for the party chairmanship. But a top Ford bureaucrat like Clements is in no position to exploit that issue.

At first the race looked like a test of strength between two Texans who covet the 1980 GOP presidential nomination: George Bush, a longtime friend of Clements, and John Connally, Hutchison’s mentor in winning the chairmanship. But Connally virtually endorsed Clements when he let it be known he wished Hutchison had run for something else. Many Hutchison followers feel betrayed, but former Democrat Connally has little clout with the Republican rank and file, who regard him as a John-come-lately. Several key Dallas Republicans, knowing the importance of money in a close race against Dolph Briscoe, have also cast their lot with Clements. But Briscoe may not make it to November and Clements probably won’t either; in what is supposed to be the party of the rich, money is not enough. Hutchison by 12.

State Treasurer

One of the state’s most downtrodden minorities has had only one of its own elected to statewide office. But if Harry Ledbetter can unseat incumbent Treasurer Warren G. Harding, a second Aggie will break the ice. Ledbetter, a former Texas A&M quarterback (1965 to 1967), carefully built an Aggie network during a recent term on the alumni board. He’s gotten contributions from people who have never been involved in politics and has enough money and support to make the race interesting.

He also has an issue. No agency in Texas has been managed as badly as the state treasury. For years as much as half the state’s money languished in bank accounts that drew no interest. (California has 97 per cent of its money in interest-paying accounts; Louisiana 99 per cent.) Simply by doing some cash-flow forecasting the state could save millions.

What Ledbetter doesn’t have is the support of the big banks. When Dewey Presley, president of Dallas’ First International Bancshares, decided to support Harding, who was a longtime Dallas County treasurer before Dolph Briscoe appointed him to the office left vacant by Jesse James’ death, the race was all but decided. Why should the big banks care? Well, four of them (First National and Republic in Dallas, First City National and Texas Commerce in Houston) have, on the average, about 40 per cent of the interest-free money in their coffers.

Harding is an improvement over James, which wouldn’t be hard, and under the pressure of the campaign has raised the state’s ratio of interest-bearing accounts and the required rate of interest. But he has disclosed no flicker of interest in modern money management techniques. Texas is a state with a long history of distrust of big banks, and if Ledbetter can raise enough money to get that issue across, he has a chance. He is articulate and smart, but he’s fighting an uphill battle against voter apathy and a familiar name. He deserves better. Harding by 7.

Agriculture Commissioner

The best Texas politician since Lyndon Johnson is named John—not Connally but White. The veteran (26 years) commissioner of agriculture still holds the honor of being the youngest person ever elected to statewide office in Texas. He ran the smoothest functioning state agency and was an innovative administrator who reshaped a caretaker bureaucracy into an aggressive promoter of Texas agriculture. And he did something no one else has been able to bring off: win the confidence of both conservative and liberal Democrats. Who but White could head the Texas presidential campaigns of both George McGovern and Lloyd Bentsen? Only one thing is clear about the next commissioner of agriculture: he will not be cut from the same cloth.

The choices are the incumbent Reagan Brown, a former Dolph Briscoe aide appointed by the governor when White left for Washington last May, and Joe Hubenak, a good-natured but less than spectacular state representative from Rosenberg. Neither has managed to persuade anyone who isn’t a farmer or a rancher why they should care who runs the agriculture department. Surprisingly, the agency does have a lot of functions that affect people who think milk comes from cartons instead of cows. It regulates pesticides and is something of a bureau of standards, checking everything from gasoline pumps to grocery scales. But the candidates have spent most of their time in the countryside. It may occur to one of them that there are a lot of votes to be won in big cities these days, but then again it may not.

Although Brown has the huge advantage of incumbency and has done nothing to mess up the administrative machinery he inherited from White, Hubenak has a few things going for him. As chairman of the House Agriculture and Livestock Committee, he is well-known in rural areas; he even made a modest splash statewide several years ago by declaring war on fire ants. (Hubenak’s pronunciation of far aints has passed into legislative legend.) Hubenak has scored some points with claims he knows more about farming (Brown taught at A&M, while Hubenak is a farmer); and Brown, who has never run for office before, shows signs of overreacting and making other campaign mistakes. One portent of a close race is that the incumbent has had trouble raising money—Hubenak has too, but that is a fact of life for challengers. If Hubenak had a common name like, say, John White, or was like John White, the race would be a toss-up, but by the time city voters get to this point on the ballot, they’re in a mood to go with whatever sounds familiar. Brown by 8.

Railroad Commissioner

Though he didn’t campaign at all, Jerry Sadler led the field for railroad commissioner in 1976 simply because voters remembered his name. Unluckily for Sadler, in the runoff they remembered why they’d remembered. As state land commissioner in the late sixties, Sadler gained notoriety for trying to choke a newsman and a state representative. Though cynics suggested that choking reporters and legislators might turn out to be a political asset, Sadler’s antics cost him his job.

Now Sadler is running again, and just to refresh voters’ memories, so is Jake Johnson, Sadler’s legislative victim back in 1969. It is worth noting that he was one of two Jake Johnsons in the House simultaneously; colleagues differentiated them by calling one Fat Jake and the other Crazy Jake. The one on the ballot this year shows no sign of corpulence.

As usual, there is an incumbent in the race; only once since 1941 (in 1976) has an open seat been available. The oil and gas industry—which either regulates or is regulated by the commission; sometimes it’s hard to tell which—has been well-served by a tradition of early resignations followed by sympathetic appointments. The anointed candidate this year is John Poerner, a former Hondo legislator who, like Agriculture Commissioner Reagan Brown, was on Dolph Briscoe’s staff at the time of his appointment.

In fairness to past commissions, a healthy oil and gas industry has obviously been good for the state. But the agency has only recently begun to perceive that the interests of the public and the industry may not always be identical. Poerner hasn’t been on the commission long enough to establish a record, but he has shown no indication of being the shameless apologist for the industry that his predecessor, Jim Langdon, was. Ordinarily money and incumbency would make Poerner a prohibitive favorite, but he is a complete unknown, and with so many other races attracting attention, it will be hard for his rather awkward name to penetrate public consciousness. Anything could happen, but in the end the industry usually has its way. Poerner by 10.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Austin