Back when all I cared about was rock and roll, my weekly forays to the record store inevitably meant buying twelve-inch British singles for the B-sides and hand-numbered indie 45’s. Then I became obsessed with hockey. Ever the obscurist, my more modest haul of pucks also favored limited and little-known editions from extinct Texas teams: the Waco Wizards, the El Paso Buzzards, the Amarillo Rattlers, the San Angelo Outlaws, the San Angelo Saints, the Central Texas (Belton) Stampede, the San Antonio Iguanas, the Lubbock Cotton Kings, the Abilene Aviators, the Fort Worth Fire. Alas, I never did obtain vulcanized rubber with a Border City (Texarkana) Bandits logo.

I also never figured that the many pucks I got while following the Austin Ice Bats for twelve years would fit into that collection. This past March, a franchise that debuted with a sold-out, televised game in front of 7,500 people at the Travis County Exposition Center played what was probably its final contest in front of less than 500 people at Chaparral Ice, a private rink where you can also learn to figure skate or join a late-night beer league.

My love of hockey started in Philadelphia, but it was consummated in Texas, where, implausibly but irresistibly, we have the most pro hockey teams of any state (or province!) in North America. The Western Professional Hockey League helped fuel this boom in 1996, putting five of its “Original Six” franchises within our borders, then adding half a dozen more over the next three years. The rival Central Hockey League was already in Fort Worth and San Antonio; Gordie Howe’s old team, the Houston Aeros, had been resurrected by the International Hockey League; and of course, the Dallas Stars had moved from Minnesota to the Metroplex, bringing the NHL to Texas in 1993. Just before Thanksgiving 1996, I joined the Ice Bats on a fourteen-hour road trip to New Mexico and wrote about them for the magazine (see “The Ice Bats Cometh”); I got back on the bus for the entire second season to research my book Zamboni Rodeo.

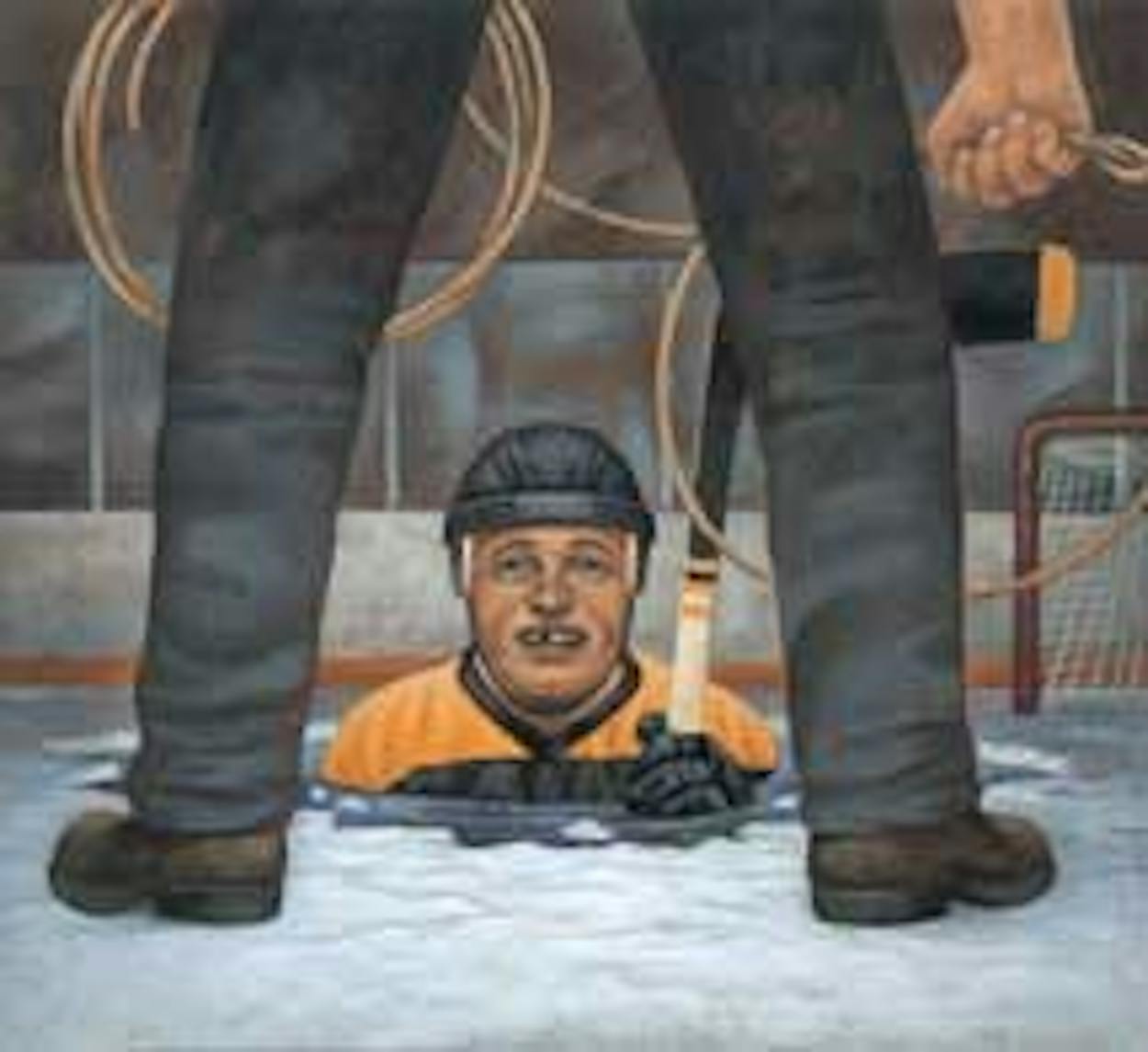

As the most appealing market—thank you, Sixth Street— Austin was the crown jewel of the WPHL, even if the jewel was sometimes made of paste. The Expo Center lacked reliable climate control, paved roads, and during one lengthy renovation, indoor plumbing. What it had was tickets people could afford and the same community dynamic as fall Friday nights; referring to your favorite team as “we” carried a lot more weight when you served the players dinner as they boarded the bus to Shreveport. The Bats’ poster boy was 21-year-old rookie Ryan Anderson, an impish, loose-fisted roofer’s son from Manitoba who was revered more for his heart and penalty minutes (1,283 over six seasons) than his skill. But he became a better player every year, and in an itinerant business, the fact that he still calls Austin home means more than his limited goals and assists. A bush-league franchise has the luxury of emphasizing fan relations and intangibles because there’s nothing that exceptional about exceptional achievement if you aren’t in the Show.

Some of the Texas teams that didn’t make it shouldn’t have existed in the first place (Abilene, for instance, could not sell beer at the arena); others fizzled due to meddling, underfinanced, larger-than-life owners (after declaring bankruptcy, El Paso owner Billy Davidson was accused of sneaking into the locker room and stealing his former players’ skates). But many were done in by the sport’s evolution. Since the WPHL merged with the CHL, in 2001, it has been dominated by expansion teams that play in new arenas and share in the accompanying revenue, including parking, concessions, and corporate boxes. Thus the Rio Grande Valley Killer Bees and the Laredo Bucks (both established in 2002) became more viable than the Ice Bats, which had long hoped to get their own building in suburban Cedar Park. Instead, they were hip-checked from the market by the Dallas Stars, who plan to put their American Hockey League affiliate there as early as 2009.

The move is not without precedent. When San Antonio voters approved the funding for the AT&T Center, the Spurs started their own AHL team, the Rampage, in partnership with the NHL’s Florida Panthers. This killed off the CHL’s Iguanas, Austin’s biggest rival at the time. There are still fans in San Antonio who refuse to watch the Rampage play, partly out of a genuine preference for more-fan-friendly and rough-and-tumble lower-level hockey and partly because they hold a grudge. So it’s no surprise that some loyal Bats fans see the big bad Stars as something like the Marriott hotel that’s forcing out beloved downtown Austin restaurant Las Manitas.

But the Stars are ill-cast in that role. They remain an underdog in their own market compared with basketball, football, and baseball, and they remain an underdog in their own sport compared with cities like Toronto and Philadelphia. Other than Colorado, which already had a lengthy collegiate hockey history (to say nothing of real ice and snow), Dallas is by far the most successful team outside the hockey belt, and at press time, the Stars were playing Detroit in the Western Conference finals. And there probably would have never been an Austin Ice Bats if there hadn’t been a Dallas Stars. They were even for a time co-owned by several people with Stars ties, including original owner Norman Green.

Howe’s Aeros and a few older, short-lived teams aside, the Stars are hockey in Texas, and their base is not just Dallas—it’s everyone who speaks the secret language in the state and, especially, everyone who plays the game. With the Stars’ support, youth and high school hockey have been booming (Stars president Jeff Cogen has referred to the team’s eight recreational StarCenters as “fan factories”). The Stars-sponsored midget major AAA team for college prospects was recently cited by Canadian bible The Hockey News as one of the five best in the country, right up there with the Minnesota prep school that NHL star Sidney Crosby played for. If you happen to see the roster of the University of Wisconsin— Eau Claire’s women’s hockey team, among the sixteen Minnesotans and one player from Utah you’ll find Lauren Havard from San Angelo. Pro hockey didn’t last in her hometown, but it surely had an impact.

So, soon hockey fans in Austin—I mean, Cedar Park—will be cheering for AHL prospects, guys who hope to follow in the footsteps of Modano, Turco, and Morrow. Guys who are expected to develop into the best few hundred hockey players in the world, or maybe even the best dozen. But they learned to love the game by watching guys who weren’t even in the top thousand. As a franchise that’s both mindful of big-picture history—three numbers from the Minnesota era hang at the American Airlines Center—and nurturing of all the frozen-water roots that they first planted fifteen years ago, perhaps the Stars ought to do something the Bats never managed: Retire Ryan Anderson’s number 11. That would tell the city’s hard-core fans that their Ice Bats weren’t driven out of business. Instead, they finally got called up.