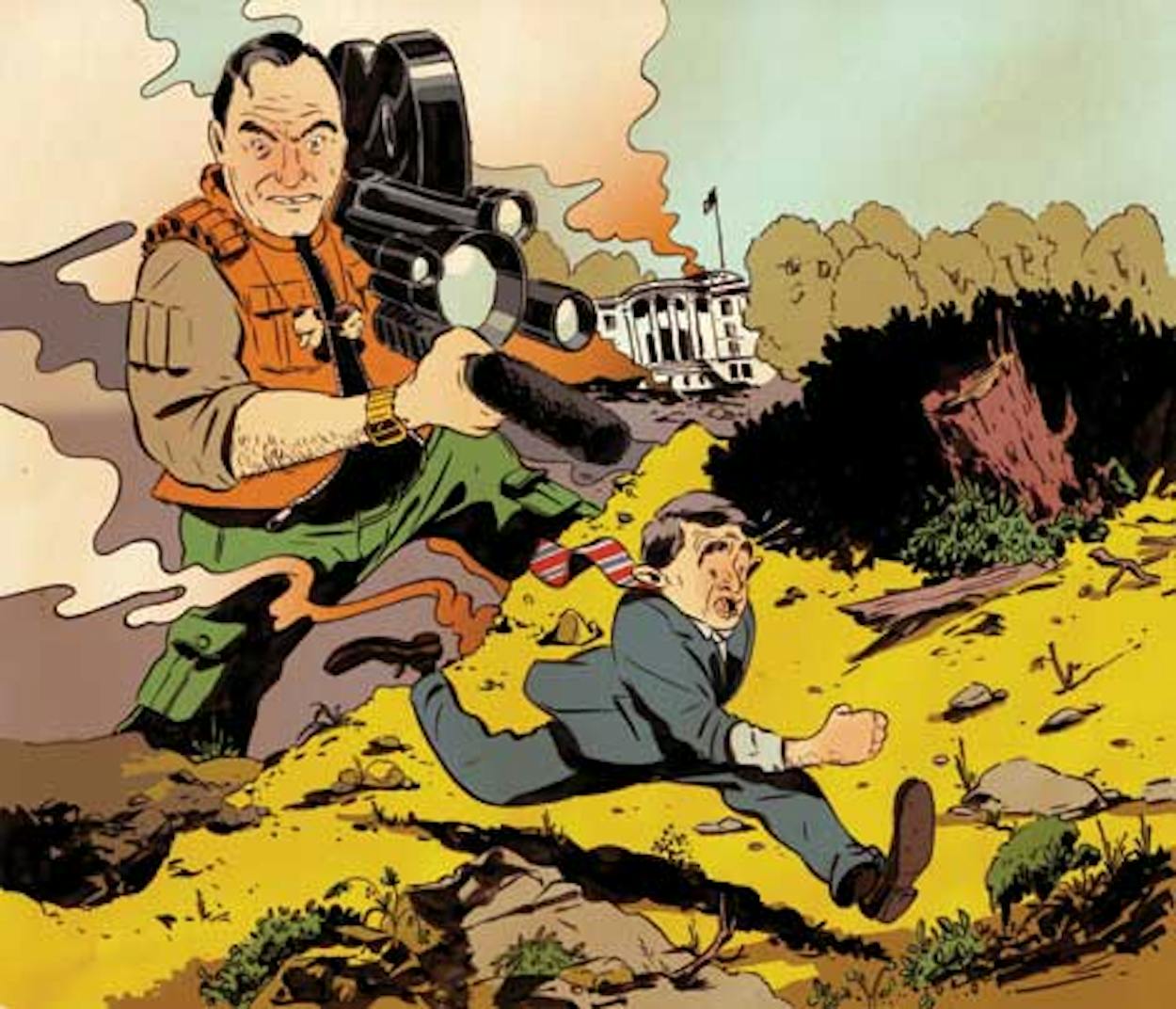

Will W. clumsily stoke the partisan flames, with Bush haters cheering and Bush lovers jeering, or will the infamously incendiary director upend our expectations? Are we in for a conspiracy-laden diatribe along the lines of JFK or something more sober and serious, like Nixon? To discuss all that and much more, editor Evan Smith and senior editor Jake Silverstein convened a diverse group (film critic, campaign strategist, screenwriter, presidential historian, indie film guru) over dinner at Louie’s 106, in Austin. On the menu: fact versus dramatic license, how to tell a story whose narrative arc is ongoing, and what the last scene should be before the credits roll.

Douglas Brinkley

Douglas Brinkley is an author and a professor of history at Rice University, in Houston. He has written biographies of Jimmy Carter and John Kerry, edited Ronald Reagan’s diaries and a three-volume collection of Hunter S. Thompson’s letters, and chronicled Hurricane Katrina’s effects on New Orleans and the Mississippi Gulf Coast.

Matthew Dowd

Matthew Dowd was a senior strategist for George W. Bush’s 2000 presidential campaign and the chief strategist for the president’s reelection bid, in 2004. He currently serves as an analyst for ABC News and is the author of Applebee’s America: How Successful Political, Business, and Religious Leaders Connect With the New American Community.

Christopher Kelly

Christopher Kelly, the chief film critic for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, is one of Texas Monthly’s writers-at-large and the magazine’s Hollywood, TX columnist. He has written for Slate, the Chicago Tribune, Salon, Film Comment, Premiere, and numerous other publications. His first novel, A Push and a Shove, was published last year.

John Pierson

John Pierson, a clinical professor in the Radio, Television, and Film Department at the University of Texas at Austin, played a pivotal role in bringing the earliest work of filmmakers Spike Lee, Michael Moore, and Richard Linklater to the big screen. He is the author of Spike, Mike, Slackers & Dykes: A Guided Tour Across a Decade of American Independent Cinema.

Anne Rapp

Anne Rapp is a screenwriter who has spent sixteen years as a script supervisor on more than twenty feature films, from Tender Mercies to That Thing You Do. Her screenplays for Cookie’s Fortune and Dr. T and the Women were directed by Robert Altman. She also co-wrote the musical A Ride With Bob with Ray Benson, of Asleep at the Wheel.

1. Full Disclosures

SMITH: Let’s begin by stipulating that none of us have seen W. We’ve only seen the trailer and read stories about it, but that’s okay. We can still have an intelligent discussion before seeing the film.

DOWD: Well, you can make the argument that the film was made before seeing the end of the presidency.

SMITH: That’s right. So what I want us to get at is the theory of the film. Don’t we know, since this is an Oliver Stone movie about George W. Bush, everything we need to know? Don’t we know, without even having seen a frame of it, what its point of view is going to be?

KELLY: I think that’s a reasonable-sounding statement that Oliver Stone should be taking advantage of, because he’s certainly developed his reputation for being incendiary and left-wing. If he was smart, he would totally upend all of our expectations. The trailer we’ve seen certainly doesn’t suggest that he’s going to do that.

BRINKLEY: It’s almost irrelevant if we’ve seen the film. Oliver Stone is someone we all know. He’s made a series of films that have had a huge impact. At times, they’ve been frustrating for me as a historian, because I’ve found them to be historically inaccurate—but then what film in Hollywood is accurate? I look at an Oliver Stone film the way I look at a Michael Moore film: It’s incendiary. It’s something that’s meant to create controversy. There are people on the right who make similar films. When Mel Gibson does a film about Christ, people who haven’t seen it still get worked up.

PIERSON: Sight unseen, we don’t know if this is satirical or serious. Nixon is not satire in any way, shape, or form. It’s a very serious consideration in a nuanced way of Richard Nixon, someone Stone had been obsessed with for a long time. We don’t know, despite the trailer and the materials that are out there, what the tone of this film is going to be.

DOWD: I don’t think you need to know the answer. Has any Oliver Stone movie affected, in any kind of real way, how Americans think or what they believe about a president? Do his movies have any historical or present-tense value? They’re popular entertainment vehicles, but they don’t add anything to the historical view of presidents. And in the present day, I don’t think they’ve affected anyone’s view of a president.

KELLY: You don’t think people view the JFK conspiracy differently because of JFK the movie?

DOWD: No.

KELLY: I’m case study number one. I was in high school when that movie came out. It informs my understanding of the Kennedys more than anything I’ve ever seen.

DOWD: The average American already knew there was some weird, crazy conspiracy going on. They already thought, “Yeah, we don’t really know what happened—he gets shot, and there’s Lee Harvey Oswald and Jack Ruby.” I don’t think the movie added anything to that in Americans’ minds.

BRINKLEY: The Kennedy movie has had a profoundly negative effect. Nobody knows what John F. Kennedy’s policies were on foreign affairs or what he did with GATT [General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade]. They just know, “Well, I heard . . .” Stone’s history is often very schlumpy. But I admire the fact that the guy is a bomb thrower who makes us rethink things.

PIERSON: Just as a point of clarification, JFK isn’t really about the Kennedy presidency. It’s about Jim Garrison.

RAPP: There’s a line in Nixon that says everything about Oliver Stone and how he gets into this material and why he makes these kinds of movies. Pat Nixon is asking for a divorce, and the president is begging her not to divorce him, and she says something like, “This isn’t political. This is our life.” And he looks at her with this complete innocence and honesty and says, “Everything’s political.” When I heard that, I went, “That’s Oliver Stone. That’s who he is.” Everything is political to him. That’s why he sometimes pisses me off. But the thing is, he’s so honest in his movies that you have to respect him.

BRINKLEY: That’s what an artist is.

RAPP: Even though it’s the opposite of what I do and the opposite of what I want to do and the opposite of what I sometimes like.

DOWD: I totally agree with you on all that. You walk away from his movies, whether you agree with him or not, thinking you saw something very interesting and telling.

SMITH: So is it unfair, as John suggests, to assume this movie’s going to be negative?

DOWD: I don’t think it’s unfair.

RAPP: I can guess what this movie’s going to be.

PIERSON: I didn’t say negative/positive. I said satirical or serious. That’s a different question.

SMITH: Talk about that.

PIERSON: Nixon was a very serious movie. Many people would think that Nixon was an easy target to satirize. That’s not what Oliver Stone happened to do in that case.

RAPP: I think the Bush movie is far harder for Stone to do well. My guess is that it won’t be as good. Bush has been spoofed and satirized from every angle. No leaf goes unturned in our culture today. Every moment will be like, “Oh, I’ve already heard that one. I’ve already seen that one.” You know they’re going to have the Bushisms we’ve all heard.

PIERSON: The fact that “misunderestimated” is in the tagline would suggest that there’s something fundamentally satirical here.

DOWD: It’s going to be one of two things. It’s either going to make you laugh at Bush or be pissed off at Bush. It’s going to make you say, “This is a joke, and I’m laughing at this guy,” or “It really pisses me off that this guy’s sitting in the Oval Office doing this kind of crap.”

KELLY: What was so affecting about Nixon is that you had neither of those reactions. I don’t think Nixon’s a perfect movie, but the character generated unexpected pathos.

PIERSON: He was played by a real actor, Anthony Hopkins. Josh Brolin’s great—I don’t want to trash-talk him—but he’s not Anthony Hopkins.

DOWD: Nixon was a tragic figure, and the movie portrayed the tragedy of him personally and as president. I think most people had a view of Nixon that way.

KELLY: Nobody expected a tragic treatment of Nixon from Oliver Stone.

DOWD: But I wouldn’t have walked in and said, “I’m going to laugh at Nixon.” I would be shocked if you don’t walk out of the Bush movie laughing at him.

II. The Political Effect

BRINKLEY: When Nixon came out, we had already had All the President’s Men. There had been serious movies that had a kind of dramatic effect. Nixon was Oliver Stone trying to make a Shakespearean story in a modern context. Whereas the Bush movie’s timing cannot help but be seen as Stone trying to have an influence on the election. My fear is that he’s just like Dan Rather: “We’re going to get him with the letter!” For all the accolades he gets, Stone has high negatives with a lot of Americans, and I’m not sure people are going to be excited about seeing this movie. I think a lot of swing voters are going to be angry that the Hollywood left is interfering with an election and trying to demean a sitting American president.

DOWD: The movie is being released three weeks before Election Day. That decision is not accidental, and that’s its importance. Depending on how it turns out, it could have a positive effect for McCain. Laura Bush is actually a key part of that, because the American public loves her—she’s a great woman. If the movie goes off on her, you could have a real backlash.

BRINKLEY: It’s not accidental. He may be thinking he’s helping defeat McCain, but it could boomerang on him. Look how the Ronald Reagan miniseries boomeranged terribly on CBS. When you’re showing an American president, a symbol of our country, in a deeply negative light, there are negative consequences. The hard left and hard right are often blind to that reality.

PIERSON: The release date is not his choice; it’s his distributor’s. Even though it’s a lower-budget movie for him, Stone is not that bankable right now. It’s a $30 million film, and they’re going to spend $30 million releasing it. Obviously, from their point of view, the release date is timed to make the most money. They assume that it will make more money by coming out three weeks before the election. That may or may not turn out to be true.

BRINKLEY: Why would you run it in February or March? The window is now.

PIERSON: This is the hot moment. No debating that. You brought up Michael Moore earlier. The timing of the release of Fahrenheit 9/11 couldn’t have been better in terms of its commercial success. But its impact in mobilizing and catalyzing certain elements of the other side was at least equal to whatever it did to mobilize Democratic voters. That’s why, in the end, the only credit you can give it as a political factor is one that was sort of zeroed out.

KELLY: Michael Moore flat-out said, I have made this movie to get George Bush out of office. Oliver Stone said nothing of the sort.

PIERSON: Right, but his entire career led him to a point where he believed that he was having an impact that he now knows he doesn’t have.

DOWD: If I were Barack Obama and I presented an argument at the end of this election that was similar to what Oliver Stone was saying, it could be easily dismissed. It doesn’t necessarily help Obama to have a movie that makes his argument less substantive.

BRINKLEY: I agree 100 percent. This movie has the potential to ultimately do damage to Obama.

SMITH:Why?

BRINKLEY: Because there’s still a reverence for the office of the presidency in this country. When you start taking a sitting president’s family apart in the way that I saw in the trailer—the drinking, that fratness, the caricature of Bush—people will be upset. The left will love it, but a lot of Middle America will say, “This is disgusting.”

SMITH:So it’s not that Bush is necessarily sympathetic but that the office of the presidency is.

DOWD: Members of his family are sympathetic.

SMITH:Bush the elder.

DOWD: And Laura.

RAPP: Laura’s very sympathetic.

DOWD: What would be interesting or surprising to me is if the movie actually conveys what some people, especially the liberal left, don’t understand about Bush, which is that the guy is a lot smarter than they think. He’s not just some doofus who bumbles around, someone created by Dick Cheney and Karl Rove to do their bidding. If the movie presented a guy who is smarter and more manipulative in his relationships, that would be news to a lot of people. And there would actually be an element of truth to it. The idea has been that you either like Bush or you don’t, that everybody around him is going, “We like him because he’s a simple guy,” or “We hate him because he’s a simple guy.” There’s much more nuance to him than that.

RAPP: I don’t think Oliver Stone will do that.

KELLY: Neither one of you seems to think he’s capable of making that kind of movie, when everything he’s done before would seem to suggest that he is.

DOWD: I don’t think he would have had access to anybody who could have told that story. Everybody he had access to would have been peripheral, would have repeated the talking points.

RAPP: Everyone knows every bit of dialogue in there. He’ll say “nukular” ten times. We’re bored with that. I think the movie flirts with insulting a certain segment of our society: the middle, the on-the-fence voter. “You don’t have to show me Bush chugging vodka at a fraternity. Let me have my own opinion. Let me figure it out myself. I’m a smart person. I can judge this man by what I’ve seen.”

DOWD: It’s interesting you say that, because in order for Barack Obama to win, he’s got to win people who voted for Bush and liked Bush and respected Bush at one point in time, if not twice. Obama has to get to a place where he can say, “I can understand why you would’ve done that and there’s some good things about him, but he took the country in a bad direction.” As opposed to, “You’re an idiot for having voted for this guy. This guy was just a fraud.”

SILVERSTEIN: So if you’re advising Obama, how do you tell him to handle questions about the movie?

BRINKLEY: “I didn’t see it.”

DOWD: I would say, “It’s entertainment. It’s a movie. It’s not a documentary on the presidency. I haven’t seen it. I don’t have time. I’m running for office.”

III. Will It Play In Peoria?

SMITH: If you assume that, according to the most optimistic polls, Bush’s approval rating is in the high 30’s, more than 60 percent of the country thinks, “Enough of this guy. Get him offstage already.” Or should that be, “Get him off the screen”?

PIERSON: If you look at documentary performance since Fahrenheit 9/11—which came out at the perfect crest of the wave, when people wanted a rallying point for feelings of anti-Bushism—anything that has remotely had some sort of anti-Bush position as a starting point has essentially had no audience.

DOWD: How much of a fatigue factor is there? Does this movie really have an audience?

RAPP: I don’t know that it does.

BRINKLEY: It has an audience, and it’s Bush haters and Oliver Stone lovers. The reason I came here tonight, even though I never talk about a movie if I haven’t seen it, is Oliver Stone. Oliver Stone is Robert Rauschenberg when he put a tire around a goat’s midsection. Or Allen Ginsberg in the middle of the Eisenhower conformity saying, “America . . . go eff yourself with your atom bomb.” Or Norman Mailer telling off Lyndon Johnson at a rally over Vietnam. I’m glad we have people like Stone in our society. They fail a lot, they create a lot of bad movies and bad poetry and bad art, but it’s exhilarating. There aren’t that many other filmmakers who would move us to be here.

SMITH: If this were Mike Leigh’s George W. Bush movie, I suspect we would not be having this dinner.

KELLY: I would be here for that. But I still think we’re underestimating Oliver Stone. You’re talking about an artist who’s capable of taking information that everyone knows and transforming it into an utterly transfixing, entrancing three-hour movie that, every time it’s on HBO, I sit, stop, and watch. The rest of my evening’s finished.

DOWD: I’m wondering if the timing for a film about Bush missed it by about two years.

KELLY: I agree with you, except I think there’s a ten-year miss in the opposite direction. I want to see Oliver Stone’s version of W. ten years from now.

BRINKLEY: You could make an argument from Stone’s point of view that in a decade the film won’t have the visceral effect that it will today. When presidents leave office, we tend to give them upward revisionism—even Jimmy Carter or Gerald Ford. Nixon has not experienced this because of the tapes on which he makes anti-Semitic slurs, but by and large, we get a little nostalgic. I think Stone is giving Bush a big boot before he leaves office. “You’re not warm and fuzzy. We’re not going to give you a free pass into the Hall of Ex-Presidents. We’re going to remind people of what a menacing little weasel you are.”

DOWD: It’s very unusual for a president not to have a rise in the polls by now. Reagan’s numbers started rising at the end. Clinton’s numbers rose. Basically, the nominees for the next election are chosen, and the voters think, “Okay, we didn’t like what this guy did, so we’re going to start thinking, ‘Goodbye. It was nice knowing you and all that.’” Bush is stuck. He hasn’t moved for two years.

BRINKLEY: He has a chance at revisionism because his biggest foreign policy accomplishment is going to be, “After 9/11, I created Homeland Security and we weren’t attacked on my watch.” You don’t want to say that now, because it’s a knock-on-wood situation, but they’re going to try to sell it.

IV. Does It Tell the Truth?

SMITH: I don’t think we’ve answered the question of factual accuracy. Anne, as a screenwriter, how much license is it permissible for Stone to take in the telling of this story?

RAPP: Oliver Stone has already set his precedent, and we accept it. I don’t think we’re going to hold him to the same standard as another filmmaker. I don’t know if this is a good thing or a bad thing, but we could write down twenty great directors right here who could have done this movie and I might not see it. I’ll go see it because Oliver Stone did it.

KELLY: Isn’t he like Michael Moore in that everything he’s put in every movie has some basis of truth somewhere?

RAPP: I think so. I think he’s operating from some honest place in his own gut.

BRINKLEY: The whole time we’ve been talking, I’ve been staring at a picture of Tom Mix on the wall. Now, is that really what a cowboy was? Don’t you read the real history of Texas, with the slaughtering of Comanches? Yet we accept Tom Mix movies or John Wayne movies.

RAPP: Every western.

BRINKLEY: So why can’t we have room for movies that dissent against presidents with literary and artistic freedom?

RAPP: There’s a movie that I’d like to have seen Oliver Stone make, and I’m sorry Robert Altman’s not here to make it. Did you guys see Secret Honor? It was Nixon, after the fact, back home. He walks into his office one day in the middle of all this paranoia, with monitors everywhere, and he sets up a microphone and a tape machine—he didn’t even know how to work it. It’s as if he’s recording his memoirs. And he just regurgitates every ounce of hatred and anger, and then he falls on his knees and cries and talks to his mother and plays the piano. And it’s ninety minutes. Philip Baker Hall did it onstage first, and Altman put the material on film. To me it was the perfect bookend to Oliver Stone’s Nixon, because it’s almost like watching a sequel, but it’s a completely different style. I would love to see somebody get into Bush’s head like that. I would like someone to do Bush in his office and in Crawford for an hour and a half walking around and talking to himself and recording his notes to whoever’s going to write his memoirs. That would be interesting.

DOWD: I would love to believe that a movie like that could be made about Bush.

RAPP: Yeah.

DOWD: He’s not that type of individual. He’s not the type who has hours and days of self-doubt. That’s not him.

SMITH: What about the trailer for W.? I actually think that Bush 41 comes across, to the degree that we can judge his character on the basis of that clip, as rather sympathetic.

RAPP: I was shocked at that trailer. It’s almost like somebody else did it. I can’t imagine that that is the core of this movie.

DOWD: The trailer looks like a made-for-TV movie.

RAPP: It looks like a Judd Apatow movie.

KELLY: There are some very serious actors here. Jeffrey Wright is playing Colin Powell. Thandie Newton’s playing Condi Rice. For the most part, these are actors who wouldn’t get involved in some sort of drive-by hit job, who want to play characters that are a little more complicated.

PIERSON: But it doesn’t seem to be master thespian time.

BRINKLEY: Based on the trailer, I think the movie is meant to embarrass the Bushes. Matthew, how do you believe the White House will respond to it?

DOWD: If the movie mistreats people that the public loves, they’ll make it about that. “We hate the movie, we hate the liberal left, this is what they think.”

RAPP: I think the movie’s going to be as much about Cheney and Rove and Rumsfeld as it is about George Bush.

SILVERSTEIN: There’s a chance that the film will attempt to be a tongue-in-cheek celebration of the journey Bush has taken from drunken, humble origins.

KELLY: Stone is genuinely fascinated by that journey.

SILVERSTEIN: There’s a way that that arc could be presented that is not inherently negative but sort of fascinating.

BRINKLEY: There are a lot of people in America who have drinking problems and are trying to lick ’em. I grew up in Ohio, and my friends in Ohio might say, “I kind of relate to that. I relate to Bush.”

KELLY: But the Friday it opens they’ll all be watching Intervention on A&E, not going out to see this movie.

BRINKLEY: I’m listening to this conversation and thinking that there’s one thing we might be able to agree on. If you’re going to write Oliver Stone’s biography, this is another home-run chapter. He’s inserted himself in the consciousness of our times whether we want to talk about him or not, whether we want to see his film or not. He has a genius for doing that. He has an ability to kind of throw his own vision into big national dialogues, whether it was Born on the Fourth of July or Nixon or JFK. Very few filmmakers have his talent for doing it. Some people call it narcissism run amok, some say it’s artistic genius, but Oliver Stone is a factor in our lives. I’ve always admired him for that.

DOWD: I want to speak to that, because I am all for Oliver Stone. I am all for people who want to present an argument. Oliver Stone has a truth to tell. He’s had a truth to tell in almost every movie that he’s in, and I think that’s a great thing. Regardless of what I think of this movie, it’s Oliver Stone’s version of what he believes the truth to be. It’s not just entertainment, it’s not just about making money. More power to him.

PIERSON: His most ridiculous movie was the one with the greatest historical perspective, the one on Alexander the Great. Across the centuries, the biggest chance for research, and it’s just silly.

BRINKLEY: If a student asked me about it, I would tell him not to think of Stone’s movies as history. We’re watching Oliver Stone’s mind at work. We’re walking into Oliver Stone’s movie. It’s not a story about George W. Bush.

KELLY: Isn’t every piece of history the historian’s version of the history?

BRINKLEY: But you try to be judicious with the facts. That Kennedy movie you love is bad history. That doesn’t mean it wasn’t stimulating. It may have even had a side effect of making people want to relook at the Kennedy assassination. But it was an awful piece of history. Maybe Stone can’t help himself. He may be a true believer in an ideological fervor that says America is an imperialist society that’s keeping down the world. He may have this vision from his Vietnam experience.

RAPP: The definitive Stone movie is Platoon.

DOWD: Actually, Platoon is one of his few movies that really added to the perspective of the American public. It was one of the first movies about Vietnam in which people had a chance to see the war in a different way.

RAPP: Even when I come out of an Oliver Stone movie and think, “That kind of sucked,” I can’t lose respect for him. I like the way he does his thing. I’ll see W. because he did it.

BRINKLEY: That line makes me think of “Brownsville Girl,” the song Bob Dylan co-wrote with Sam Shepard. Dylan is talking about Gregory Peck’s films, and he sings, “He’s got a new one out now/I don’t even know what it’s about/But I’ll see him in anything so I’ll stand in line.” There are people who will go see an Oliver Stone film because it’s Oliver Stone, and he’s created an America, and a world, of dissent. Too often we act like dissenters aren’t patriotic. I think Oliver Stone loves this country greatly. It’s just he expresses it in a way that sets some people off because it comes out of a deep distrust for our government.

RAPP: That’s why World Trade Center was lame compared to all of his other movies.

KELLY: It’s an utter bore. Dead on arrival from the first scene.

PIERSON: Certainly the least bomb throwing and the most mild-mannered.

BRINKLEY: He had to be decent for once.

RAPP: Let’s say you had a great relationship with your father and a horrible relationship with your mother, and they die. You write a book about your father and a book about your mother. The book about your father will be worthless. The book about your mother will be great. That’s why Oliver Stone couldn’t make World Trade Center.

KELLY: He was cowed by the subject in a way that no one would have expected from Oliver Stone.

RAPP: He probably tried too hard on that movie. He loved it the most—and he’ll go to his grave with that being one of his worst. It’ll be the baby with the disability.

DOWD: What’s going to be interesting about this movie is that it will be given extreme weight by the two sets of audiences whose minds will not be changed by it. Neither the left nor the right will be transformed by this movie, and it won’t have any real effect on anybody in the middle.

PIERSON: Once again this takes us back to Fahrenheit 9/11.

SILVERSTEIN: So how would you make this film in a way that would hit the middle?

DOWD: I’d focus on an angle that is either counterintuitive or adds something new. Everybody knows that he messed up in office and made bad decisions and fired people. He can’t speak right. There’s a part of him that’s simple and a part of him that’s lazy and a part of him that’s calculating. But there’s also the story of what happened in his youth with his father not being there and his mom losing the daughter and his becoming the person who kept his mother going. He entertained her, told her stories, made her laugh. His formative time was in there. That would be an interesting psychological tale. Not many people know it—how it led him to mess up, how it led him to do good, how that led him to the bullhorn moment. All those things would give you a window into this person, as opposed to hearing the same retread Comedy Central lines.

SMITH: If you read the leaked pages of the script that circulated on the Internet, you see that a lot of significance is given to the psychological dynamic between Bush and his dad, which plays out as a motivation for his behavior.

BRINKLEY: The left can’t give too much sympathy to the psychic life of poor W., because Dad was an ambassador and away all the time and he had to deal with home life as a rich kid when these young working kids are dying in the war. To indulge in that full human portrait of W., it dilutes the anger that is out there on the left over the war in Iraq. What if you’re a mother who lost your son in Iraq and now you’re starting to watch this Oliver Stone film, and you think, “My kid lost his life because he had a daddy problem”? It’s awful. We’re trying to elect people that are grown-ups, that are psychologically—

DOWD: You know what? That is awful. But that may be the truth. I mean, honestly. I have a son who’s sitting over in Iraq; he’s serving over there now, and I ask why. And that is god-awful. This is not the Oliver Stone movie, but maybe it is. Maybe he’s actually asking the question of how we ended up in a war that we shouldn’t have been fighting. I hope part of it tells that story in a way that’s just not the same old retread that we know but is sad and true.

V. The End

KELLY: I don’t know if anyone remembers a scene near the end of JFK, in which Kevin Costner turns to the camera and—speaking directly to Doug, no doubt—says, “It’s up to you.” That, to me, is one of the most primal moments of the last 25 years of moviemaking, because it’s the rare case of a moviemaker engaging head-on with the audience and asking them to become part of his inquiry. That’s why I’m so excited about this. I feel like Bush is a worthy subject.

SMITH: So what’s the last scene in this movie?

RAPP: This has got to be the hardest movie ever to write the ending for. I cannot stand it.

BRINKLEY: I’d go for a combination of John Ford and Dr. Strangelove. President Bush and Condi Rice riding off into the sunset on separate tanks but holding hands.

PIERSON: Jeffrey Wright getting Tasered and beaten up by the Shreveport police. That would be a good ending.

RAPP: It ends with Colin Powell walking away from the camera, shaking his head.

KELLY: Another movie everybody hates, Marie Antoinette, ends not with her getting beheaded, like you expect, but with her leaving Versailles and expressing utter sadness that this wonderful world she lived in is over.

SMITH: So it’s Bush back in Crawford looking at the mail that the post office held for the last eight years?

BRINKLEY: I think it’s with the unraveling of America under Bush’s watch: the Katrina debacle, losing our grip on Iraq, and all that. You’ll be captivated by his personal journey, and in the end, you see that all this dysfunction has led to a morass. If I were scripting it for Oliver Stone, it would be a large statement.

DOWD: That, or you go the exact opposite direction and make “The Incredible Shrinking President.” He leaves office and nobody’s listening. He’s trying to talk and nobody cares. He started out with the bullhorn and he ends up with nobody even giving a crap what he has to say.