Chapter 1

THE FIRE

Her first memory is of heroism and stardom, of great accomplishment and acclaim, even in the midst of ruin.

She was five years old, firmly in the nest of her family, at her aunt and uncle’s cabin. The adults were in the front room, sitting in front of the drafty fireplace. Maxine was sleeping in the back room on a shuck mattress, Jim Ed was on a pallet, and Bonnie was in her cradle. Maxine awoke to the sight of orange and gold flickerings the shapes and sizes of the stars, and beyond those, real stars.

The view grew wider.

Stirred by the breezes of their own making, the sparks turned to flames, and burning segments of cedar-shake roofing began to curl and float upward like burning sheets of paper.

She lay there, waiting, watching.

It was not until the first sparks landed on her bed that she broke from her reverie and leapt up and lifted Bonnie from her cradle and Jim Ed from his pallet, a baby in each arm, and ran into the next room, a cinder smoking in her wild black hair, charging out into the lantern-light of the front room as if onto a stage, calling out the one word, Fire, with each of the adults paying full and utmost attention to her, each face limned with respect, waiting to hear more.

They all ran outside, women and children first, into the snowy woods, grabbing quilts as they left, while the men tried to battle the blaze, but to no avail; the cabin was on fire from the top down, had been burning for some time already while they played, and now was collapsing down upon them, timbers crackling and crumbling. In the end all the men were able to save was the Bible, their guns, and their guitars, fiddles, banjos, mandolins, and dulcimers.

There are a thousand different turns along the path where anyone could look back and say, If things had not gone right here, if things had not turned out this certain way—if Maxine had not done this, if Jim Ed and Bonnie had not done that—none of all that came afterward would ever have happened.

Only once, looking back, it would seem that from the very beginning there had been only one possible path, with the destination and outcome—the bondage of fame—as predetermined as were the branches in the path infinite.

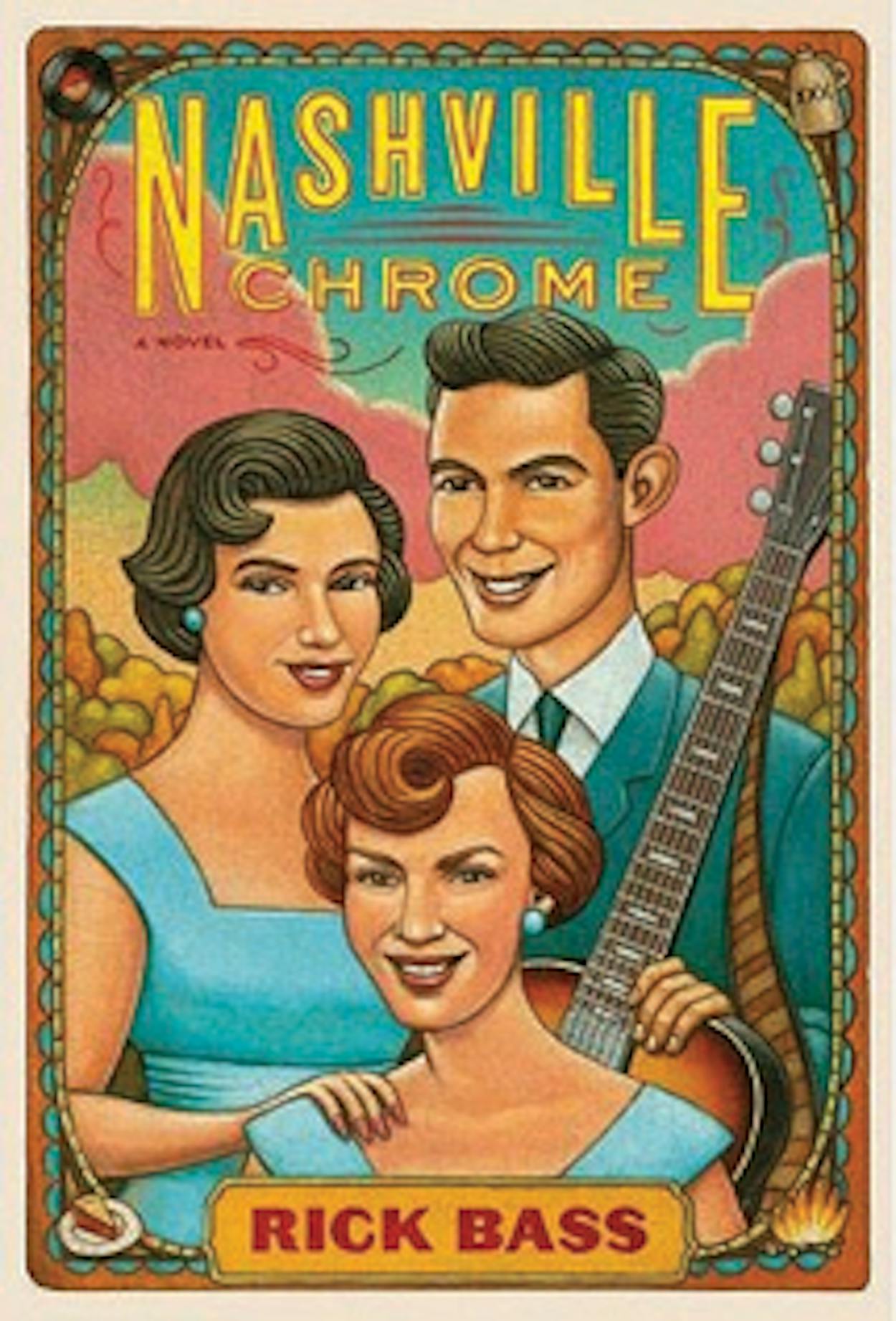

That the greatest voices, the greatest harmony in country music, should come from such a hardscrabble swamp—Poplar Creek, Arkansas—and that fame should lavish itself upon the three of them, their voices braiding together to give the country the precise thing it most needed or desired—silky polish, after so much raggedness, and a sound that would be referred to as Nashville Chrome—makes an observer pause. Did their fabulous voices come from their own hungers within, or from thrice-in-a-lifetime coincidence? They were in the right place at the right time, and the wrong place at the right time.

There was never a day in their childhood when they did not know fire. They burned wood in their stove year round, not just to stay warm in winter but to cook with and to bathe. In the autumn the red and yellow and orange leaves fell onto the slow brown waters of the creek, where they floated and gathered in such numbers that it seemed the creek itself was burning. And as the men gnawed at the forest and piled the limbs and branches from the crooked trunks, they continued to burn the slash in great pyres. The smoke gave the children a husky, deeper voice right from the start. Everyone in the little backwoods villages sang and played music, but the children’s voices were different, bewitching, especially when they sang harmony. No one could quite put a finger on it, but all were drawn to it. It was beguiling, soothing. It healed some wound deep within whoever heard it, whatever the wound.

The singers themselves, however, received no such rehabilitation. For Jim Ed and Bonnie, the sound passed through without seeming to touch them at all, neither injuring nor healing. They could take it or leave it; it was a lark, a party trick, a phenomenon.

Where had it come from, and when they are gone, where will it go?