Editor’s Note: This is the fifth and final installment in a series about the border crisis. Read the first story, about Sister Norma Pimentel and her work with the Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley, here; the second piece examines the crisis through the eyes of Kevin Pagan, the City of McAllen’s emergency management coordinator; and the third story covers Othal E. Brand Jr., one of the few politicians who has directly taken action in securing the border. In the fourth installment, we spend a day with the Border Patrol.

“You can talk with this boy,” an imposing man with a bushy white mustache tells me when I arrive at a church in Brownsville, the name of which I have agreed to keep confidential. I’m there to talk to newly arrived immigrants.

The boy is small for a sixteen-year-old—five-foot-five at most, probably no more than 120 pounds. His face is bony and gaunt. A dark-green windbreaker that he has received from a church volunteer hangs on his narrow shoulders. He name is Edras.

Since Edras left his home in the Jutiapa province of Guatemala a month ago, he has often been without food. “I was a little chubby, now I’m skinny,” he tells me in Spanish as we sit down inside a spartan church classroom. “My stomach was all cramped and I looked like a skeleton. Sometimes I get stomachaches like I have gastritis.”

Edras has been in the U.S. for two weeks, and until very recently he spent most of his journey living with coyotes (human smugglers). He grew to distrust them. “They don’t feed you and they’re always on drugs,” he says. “They’re really high, so they don’t know what they’re doing.” Two nights earlier, he says, the coyotes decided “they didn’t want to be responsible for us anymore.” They dropped him and a group of other immigrants off in a field. It was dark, and they didn’t know where to go. The smugglers, Edras says, didn’t care. “And they kept our money,” he adds.

After the smugglers left, Border Patrol arrived. “Five of us got away [from them],” he continues. “The rest were apprehended. We went out into the street to find help, and thankfully we flagged down two trucks and asked [the drivers] to bring us to the shelter. We were very weak. I was feeling like I was going to fall and not be able to get back up. I could barely walk, and my eyes were sunken.” From the shelter—a local sanctuary for immigrants—he was sent to the church. “I’m here because they’re going to help me get papers so that Immigration doesn’t detain me.”

The man at the church told me nothing about Edras before I sat down to talk to him. A few days earlier, I had met a sixteen-year-old girl from El Salvador traveling with her mother and younger brother. They had been detained by Border Patrol and released in McAllen with bus tickets and a “Notice to Appear” in immigration court. When I meet Edras, I assume that he has traveled in a similar unit and that he has also been processed by Border Patrol or Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). The other members of his family, I figure, are probably off resting in another room. But as he tells me about his escape, it becomes clear that he is very much alone.

“So Border Patrol doesn’t know you’re here?” I ask.

“No, they don’t know,” he replies.

“Where will you go?” I continue.

“To Maryland,” he says. (He has an uncle in Baltimore who is expecting him.)

“Who is going to take you there? Are you going to go alone?”

“I’m going to leave here by myself.”

“Is someone going to tell you when you can leave?”

“Yes, the people here are going to tell me.”

“So you’re going to wait to hear what they say?”

“I’m going to wait and hear what God says. I crossed, and I’m here.”

In fiscal year 2009, Border Patrol apprehended 3,304 unaccompanied minors from Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala as they crossed into the U.S. In fiscal year 2012, the number grew to 10,146. So far this year, the number is 43,933. (An additional 12,614 unaccompanied minors have come from Mexico, but this number has remained stable over the past five years.)

Many explanations have been offered for the surge, from unconscionable levels of violence and poverty in Central America to President Barack Obama’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, from rumors of an amnesty window for undocumented children to lax border security. But all of these explanations seem incomplete on their own (and in some cases are closer to fantasies). Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala rank among the most violent countries in the world, and many young people want to flee the danger, but that was as true in 2009 as it is today. DACA applies only to immigrant children who have lived in the U.S. continuously since June 15, 2007, and it takes considerable speculative leaps to conclude that it somehow drove the surge. Rumors of an amnesty window have run rampant in parts of Central America, but it’s unlikely that’s the principal catalyst for leaving: a comprehensive United Nations report on the undocumented minors published earlier this year found that of the 104 El Salvodoran children interviewed, “only one child mentioned the possibility of benefiting from immigration reform in the U.S.”

With stories of unaccompanied minors crossing by the raft-load, it’s easy to see how someone could characterize the surge as “an invasion,” as Texas congressman Louie Gohmert did, but most of these immigrants are surrendering upon arrival, and undocumented immigration is, on the whole, lower and more aggressively enforced than it has been in decades. (In 1993, 4,028 Border Patrol agents apprehended 1.26 million undocumented immigrants. Last year, a much larger force of 21,391 agents caught only 420,789.) Part of what has made the immigration surge so frustrating and polarizing for policy makers is that there is no single root cause and, thus, no single solution.

Sitting in the church in Brownsville, Edras offers his own personal answer for why he departed. Like many children fleeing from Central America, his family has experienced senseless violence: “Two of my uncles worked straight; they didn’t mess with anyone. So the bad guys killed them. That’s how things are there.” But typical of an immigrant from Guatemala—where the murder rate ranks fifth in the world but is less than half of what it is in Honduras—crushing poverty was an even greater factor in his decision to leave.

In Guatemala, Edras worked as a farm laborer, planting corn and beans and chopping firewood “from sunrise to sunset,” making only $5 a day. His father was sick with gout and couldn’t work, and Edras couldn’t earn enough money to buy him medicine. His mother suffered from debilitating headaches. When I meet Edras in Brownsville, the World Cup is entering its knockout rounds, and I ask him if he likes soccer. “Since I worked from five a.m. to five p.m. to try and make some money, I never had the chance to play,” he says. “I didn’t get to study much either, just a little bit.”

Edras had several friends who had made the journey to the U.S., and while he had no illusions about amnesty (he didn’t surrender to Border Patrol, after all), he had a sense of how to navigate the process. He borrowed 48,000 quetzales ($6,000 U.S.) in Guatemala and paid a smuggling network for guided passage to the U.S. A coyote brought him from Guatemala to Mexico City. Another took him farther north. Along the way, he says, the police stole his savings. “The federales in Mexico would take all our money or else they wouldn’t let us pass,” he says. “They took off our shoes to see if we had [money] hidden there.” He turned over 1,000 quetzales to the Mexican police—all the cash he’d brought with him.

Upon reaching Matamoros, the Mexican city across the Rio Grande from Brownsville, the journey further devolved into a nightmare. “We were locked up inside a warehouse for eight days,” he says. “They fed us a little bit and didn’t give us much water. From there they moved me to another warehouse where they didn’t feed us. We crossed the river on empty stomachs.”

Before crossing into the U.S., the smugglers gave Edras three options: “Option one was to give myself up to Immigration. Option two was to cross and not give myself up. Option three was not to cross.” He chose option two based on what he had heard about the process. If he surrendered to Border Patrol, he thought that he would be detained for “two or three months” at a state prison in Miami, a fate he wanted to avoid. (Though Miami does have a facility for undocumented minors, it is not a state prison, and it’s unlikely—but not impossible—that Edras would have been sent there.) Edras knew that he would eventually end up in the custody of a family member or suitable guardian—in his case, his uncle. He thought that he’d need to spend an additional $2,000 on the plane trip between Miami and Baltimore. (His uncle would need to come pick him up at a facility, but it’s unlikely the voyage would cost close to $2,000.) And he knew that he’d be wise to hire a lawyer—he estimated the cost at $3,000—before pleading his case for asylum or Special Immigrant Juvenile Status. (Asylum seekers are four times more likely to win their cases when represented by an attorney.) If he skirted the whole process, he reasoned, his passage to the U.S. would be considerably cheaper. Going through the system, he tells me, “would be like paying for two trips here.”

But evading capture comes with its own consequences. The smugglers decided to bring Edras across at a point in the riverbed called la Puerta (the Door). (The Rio Grande is a mere trickle north of Matamoros.) Border Patrol spotted his group and chased them. Edras tells me that they caught him and beat him but that he and some others managed to escape.

From there, still in the custody of the coyotes, he was transferred from warehouse to warehouse, eventually ending up at a cartel-controlled ranch in the Valley. “It’s a piece of land that has a house and everything,” he says. “There were several luxury cars. Only people with drugs hang out there. There were all sorts of things there—weapons, cuernos de chivo [AK-47s], all that. They would get really high and start shooting when we were there. We would hide in the fields. I was afraid I was going to die there.”

He was eventually taken off the ranch before being abandoned by the coyotes, chased by Border Patrol, and finally picked up by the two trucks that brought him to the immigrant shelter in Brownsville. There he called his uncle in Baltimore and his parents in Guatemala to tell them he was okay. His parents, he says, had grown sicker worrying about him over his month-long journey, but now they were happy. He was “at God’s house. Better than in the field, starving with the mosquitos.”

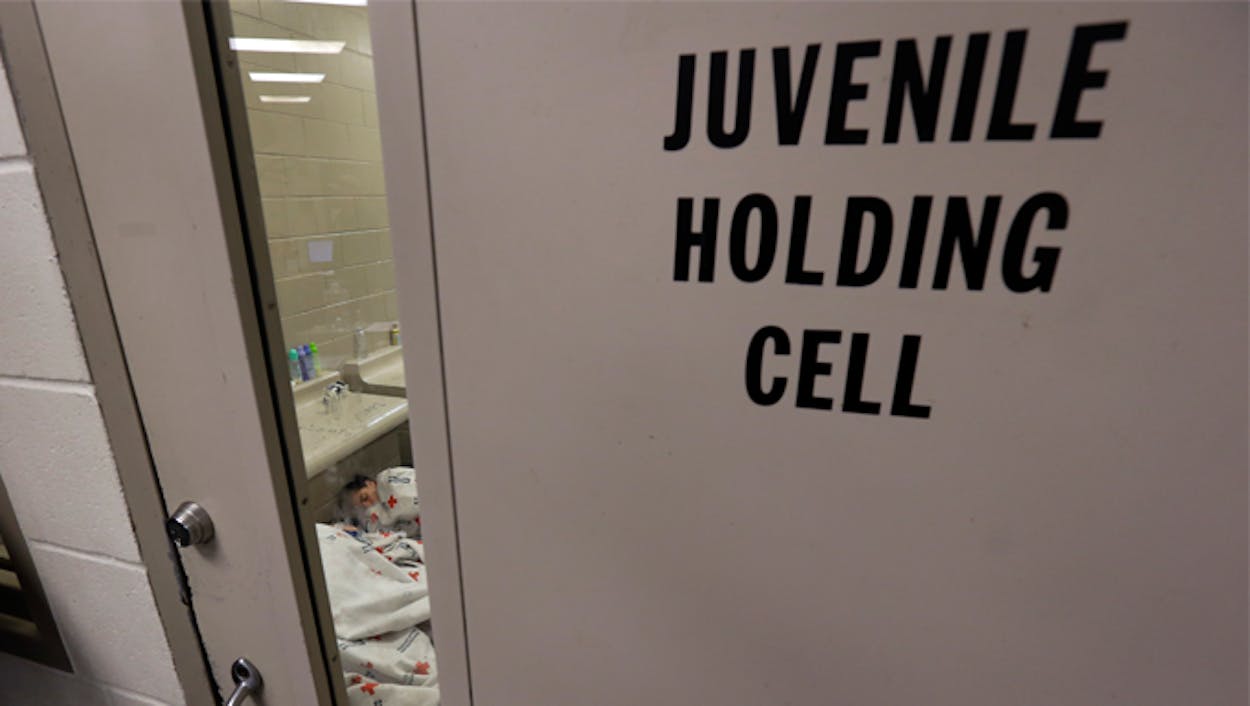

As we sit in Brownsville, Edras is safe for now. He has gotten food to eat and new clothes, but he still faces daunting obstacles. If the church finds him a lawyer and a guardian, he can likely stay out of detention while applying for affirmative asylum. If Border Patrol or ICE picks him up, they will process him and send him to an Office of Refugee Resettlement facility with other unaccompanied and undocumented boys and young men. After a stay of a month or more, he will likely be released into the custody of his uncle with a “Notice to Appear” for his hearing. When the date of that appearance arrives, he will have to plead his case, first in front of an asylum officer, and then, if the asylum officer rejects his claim, in front of an immigration judge.

Based on the story he told me, Edras may face an uphill battle in immigration court. He is not fleeing a direct threat of violence. He is not a victim of abuse. And he is not reuniting with his nuclear family in the States. He is honest about what he and his family face in Guatemala. They aren’t starving, he says, but they are poor and they lack access to basic medicine. Those reasons might not be enough to get Edras asylum, especially if the political push to expedite, and thus increase, deportations of Central American minors—led by Texas senator John Cornyn and Texas congressman Henry Cuellar—becomes law.

Edras doesn’t view deportation as an option. He owes 48,000 quetzales to the people in Guatemala who fronted his coyote fee. “If I go back,” he tells me, “I won’t be able to pay it back. Then they’ll take my dad’s land and leave him on the street.” He doesn’t have big dreams about his life in America; he just hopes to keep his head down and get by. “I don’t want to get into anything bad, any vices,” he says. “I want to work legally.” If he gets asylum, he’ll have more work to do. First he’ll need to pay off his creditors. Then he’ll send money home “so my [mom and dad] can get better, eat better, and build a good house, because we don’t have a real house, we have a shack.” Then, if all goes well, probably several years hence he’ll turn to his own needs. His goal is simple: “I’m going to make a better living for myself in the United States.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy