“Do you want to go into the Globe of Death?” Victor Flores asked. I wasn’t prepared for the question. I had met Victor, the leader of the Fearless Flores Circus and Thrill show, only a few hours earlier. I scanned his face to determine if he was joking. I glanced toward a corner of the Rio Grande Valley fairgrounds in Mercedes, where a spherical cage, made of black crisscrossing wrought-iron bars, was held upright by a few wires and stakes. The moan of content 4-H cattle drifted into the surrounding onion fields. “You mean now?”

“When we do the act,” Victor said. “we are waiting for cousins to come up from Mexico, but it looks like they will not make it, and we need someone to stand in the middle of the motorcycles, you know, when they go around inside.” He smiled, showing two sparkling gold-capped teeth. “You want to do it!” I shrugged.

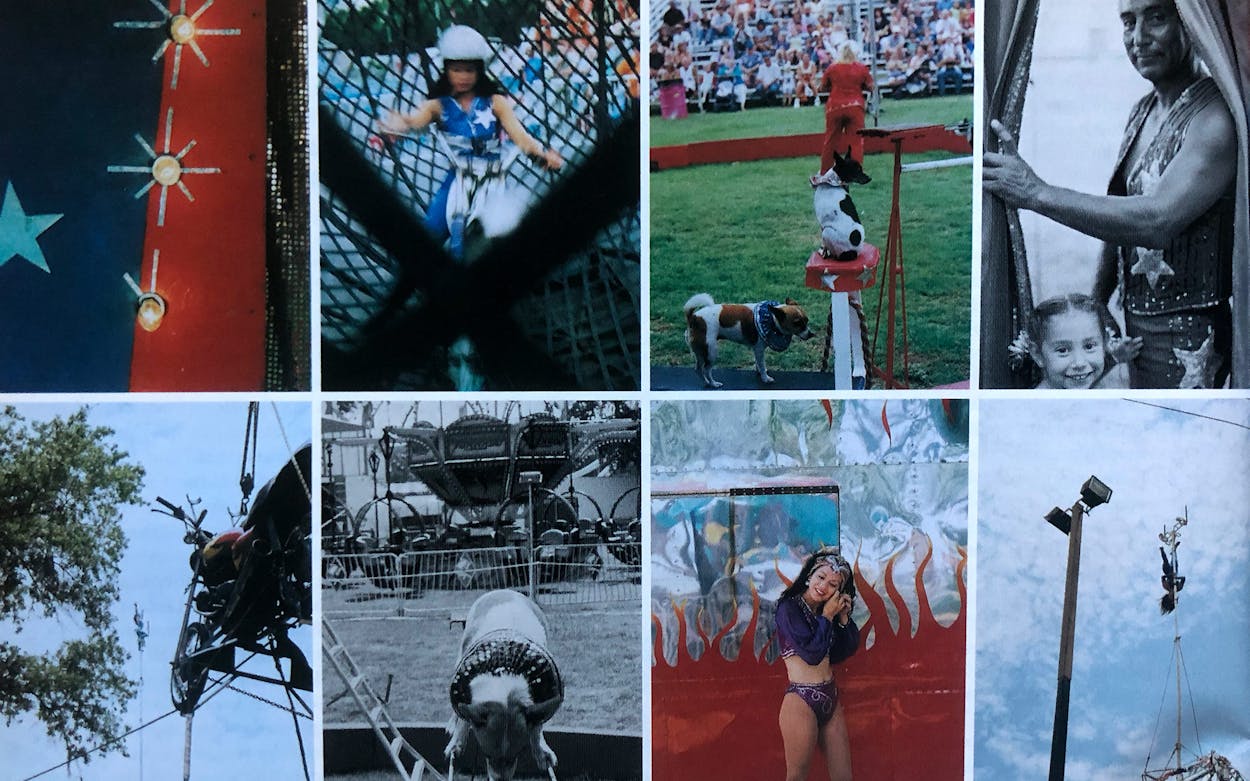

But the next day the cousins still hadn’t arrived from Mexico. By one o’clock on a 90-degree spring afternoon, Victor’s 22-year-old daughter, Frances Flores, was suited up in a polyester, cobalt-blue pant-and-vest outfit that she had made years ago for the Globe of Death act. She surveyed the family’s simple arrangement on the grass-spotted fairgrounds: stage left, a contraption called a breakaway sway pole; a white-and-cherry-red center ring decorated with hand-painted blue diamonds; stage right, the Globe of Death. She ripped off her silver helmet, sprang off her motorcycle, and wiped the sweat from her upper lip as she turned down the heavy-metal guitar music blaring out of two desk-size speakers. Then she took the microphone and faced curious big-brown-eyed boys and girls wearing pressed denims, slouching on hay bales. Some of them dragged their prize-winning goats close to the ring, then led them back to the show barns, where the sweet cotton-candy smell of hay hung in the sunbeams. Wearing a T-shirt and jeans, I stood behind a two-paneled red-velvet-curtain backdrop and waited for my cue.

“Ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, how do you like the show so far?” Frances asked. The crowd clapped and whooped in a singsong of little squeals. “Well, all right, would you like to see some more?” Victor, who was dressed in a cobalt-blue costume similar to Frances’ and sat near the globe on his motorcycle, signaled for the audience to shout. The kids kicked and stomped and leaned forward. A group of boys wearing thick glasses whipped their heads back and forth, wagging their snow-cone-stained tongues, unable to hold still. “Yeeeeah!”

Frances laughed. “All right. Well, we have one more surprise for you. Right now we’re going to bring out somebody who will join Victor and me in the Globe of Death. The motorcycles will race within inches of her body. After that, we will come out into the audience and answer any questions you have about the Globe of Death. We will also sign these souvenir photographs for two dollars a piece.” Victor’s wife, Linda, a blond woman wearing a gold lamé pantsuit, entered the ring with a smile frozen on her face. She marched in a small circle. High above her head she held up the photographs of the Floreses posing in front of the Globe of Death. Frances continued, “All proceeds from these photographs will go into a health insurance fund for the Fearless Flores. You see, no company will cover us. Because they say this,” she paused, “is suicide.” The crowd gasped. “And now please give a warm welcome … “

I heard my name and stumbled out from behind the curtain. Frances pulled on her helmet and sped over to the globe. Linda cranked up the guitar solo, and Victor opened the metal sphere’s door. I followed Victor and Frances inside, slammed the door shut, and stood facing the audience from the bottom of the sphere, which was about two and a half times my height. Victor was sitting on his motorcycle in front of me; Frances was behind, on hers. She was close enough that I heard her say, “Smi-i-ile,” over the roar of the bikes. Victor winked and flashed a brilliant grin. “You ready?” he asked. “Remember what I said? First whistle, arms up, second whistle, arms down. Got it?”

“Got it,” I said.

“Okay.” He nodded at Frances, and they rolled their wheels back and forth in short bursts. Once. Twice.

The third time they took off. In about three seconds they had accelerated to 30 miles per hour, chasing each other around on the sides of the cage so that their bodies were horizontal to the ground.

I gritted my teeth and tried not to move. The deafening high-pitched whine from the motors and the vibrating cage rattled in waves through my stomach. I began to imagine what I would do if one of them fell or if they crashed. Should I jump up and cling to the side of the cage? Could I hold on?

Victor whistled.

I raised my hands, and Victor and Frances rode one-handed, slapping my palms as they rode around the side. Victor whistled again, and I put my hands down. They began to ride higher on the walls of the cage, turning almost completely upside down, passing each other so they wouldn’t hit each other—or me.

I spotted one girl with chubby cheeks and long black hair in the audience. She was sitting close to the cage, but she couldn’t see that I was laughing the way you do when a roller coaster is about to plunge and you’re totally helpless. She looked terrified.

Just about the time I started wondering how long the act would last, Victor whistled again. He and Frances made three more loops and came to a dead stop at either side of me at the bottom of the cage.

Linda shouted over the microphone, “Let’s hear it for the Fearless Flores!” I struggled to get the heavy cage door open. I hoisted it to the side, hit my forehead on it, and skipped over a thin cable, a little dizzy. Frances and Victor raced their bikes to the center ring and took their bows. They turned around and signaled for me to join them. I waved and darted back behind the red curtain.

I wondered how I was going to explain the past twenty minutes to my friends. I had never had any desire to follow a circus. In fact, until the day I found myself in Mercedes with the Fearless Flores Circus and Thrill Show, I had never seen a circus. They had always seemed to be like touring Broadway musicals—huge, slick, mass-marketed, and boring.

Two years ago, however, I read an obituary about a four-foot-tall elephant keeper named Tiny Tim. The circus for whom he had worked his entire life hosted his funeral under a big top in Chicago, and Tim’s casket was drawn into the tent by his elephants. I couldn’t believe such people were still around. I wanted to know more. I called circus museums and talked with archivists. They gave me the names and phone numbers and addresses for small circuses in Texas. I sent out about a dozen letters (which were returned) and made as many phone calls (to many disconnected numbers). A year later I received a call from the Fearless Flores Circus and Thrill Show of Von Ormy. Each year, they said, they were on the road about 320 days, performed at 50 sites, averaging about six hundred performances. They were doing just fine and were offended by the very possibility that they were a dying breed. Who were these people?

“The Fearless Flores, ladies and gentlemen! We hope you enjoyed the show! And may all your days be circus days!” Victor and Frances looked at each other, laughed, and went out into the audience to sign autographs.

IN BROWN COUNTY IN THE late 1800’s, a rancher named Wiley “W. C.” Clark was bitten by the show bug. Using a packhorse, he began to entertain folks at local schools and churches with magic lantern shows and a ventriloquist act that used two dummies (one, named Mike, was Irish; the other, named Snowball, was black). Over time, he ranched less and performed more. Then he got it in his head to do something big. He persuaded his business-savvy younger brother Mack Loren “M. L.” Clark to acquire circus equipment and a few wagons. W.C. hired some performers and roped his four sons into service. Together, W.C. and M.L. founded the Clark Brothers Shows, which went on to become one of the most well-known wagon shows in American circus history. And the destiny of all the following generations was put on course.

They were unrelenting. They were hustlers. They did what they had to do to get by. They looked beyond the dog and pony show, concocting ways to take bigger, more impressive risks: rings, high wire, elephant tricks, snake handling, bear wrestling. The women were as rugged as the men—and beautiful to boot. They gave birth in tents, and within a week they were back in the show, dressed in sexy costumes. All over Texas and Oklahoma, the men drove the horses and mules, and the women and the elephants walked behind. To avoid bad luck, they never wore yellow in the ring. They broke their backs and their feet and rubbed the skin off their hands and knees. They worked hard, all of them. For a short time, they got ahead.

A little over a century after W. C. Clark’s death, one family of his descendants has amassed four houses (one in Texas, two in Florida, one in Mexico), four flatbed trailers and trucks, an eighteen wheeler, two pickups, two buses, one trailer home, and two working units. The units travel independently to fairs and larger circuses, joining forces when the opportunity is financially advantageous. They are the Fearless Flores Circus and Thrill Show.

The first unit is composed of Victor, Linda, and Frances, who spend most of their time on a sky-blue bus adorned with a little blue-and-white-striped awning stretched out above the back bedroom window as if it were the umbrella in a drink. In a matching blue trailer behind the bus is Linda’s menagerie: a dozen or so pigeons, trained rat terriers, miscellaneous pet birds that constantly squeak like a cassette tape played backward, and an attentive German shepherd runt named Dog.

Victor and Linda’s son, 24-year-old Tito Flores, is the head of the second unit of the Fearless Flores. Tito is trim and muscular, he frequently wears perfectly fitting neutral-colored polo shirts, and his Matt Damon-ish face quickly changes expression from defensive seriousness to a wide-eyed, raised-eyebrow smile, as if he has just heard something simultaneously impressive and implausible. Shortly after raising his eyebrows, he will usually grab or slap a nearby object and let loose an enormous belly laugh. Tito and his gentle 25-year-old wife, Chela, travel in a cream-colored trailer with a canoe tied to the roof and pop-out walls to provide a wider living area for their animated 4-year-old daughter, Cyndel, a seventh-generation circus performer, as well as for future Fearless Flores children. (A baby boy is due September 21.)

Circuses are incurable expansionists. To survive, the small ones join up with big-top shows, either part-time or for good. Most producers these days hire human daredevils to create multi-ring shows, relying on name recognition and box-office appeal to draw massive audiences. The few remaining members of old circus families hitch themselves to one of the handful of touring circuits. If they can’t tour with a big-name group, they subsist on spot dates at large shows with recognizable names or intermittent jobs at fairs. When times get tough, they sell novelties and souvenirs.

The Fearless Flores family is a link to circuses of the past. Yet they spend their days and nights imagining a better future for the upcoming generations of Thrill Shows, which—despite the odds—makes perfect sense, once you get to know them. They are a breed apart. They have become not only the most successful generation of performers in their bloodline of Clarks but the most successful autonomous nomadic troupe of performers working in Texas today. Getting ahead is a difficult task. It requires risk, something that rules their lives like a god.

There are days, though they are rare, when Frances Flores envisions disaster. One day last March, for instance, when the wind was blowing hot as a hair dryer, she imagined flying off the white sixty-foot-tall breakaway sway pole, over the heads of the attentive group of 4-H contestants, and landing face first in the hard, cracked borderland dirt. Normally at around three in the afternoon on a similarly sunny day she would have been performing the stunt for the Fearless Flores, perhaps in a jade outfit, before about a hundred onlookers. She would have stood tall on the top of the pole, striking various gymnastic poses, taking the audience’s attention away from Victor, who would pull a pin that locked the top and bottom pieces of the pole together. She would have surprised the audience by shrieking as the pole snapped in half, the top section collapsing and swinging her down toward the ground as if she were hanging on to a giant pendulum. But on this windy afternoon, her curly black hair acted as a weather vane and she squinted as she eyed the pole. That was the only time I heard her say, “I don’t think I should do this.”

One night at dinner Victor recounted a fatal accident that occurred last year on a breakaway sway pole—one nearly identical to the one on which Frances performs. Linda put her fork down on a plate of chicken enchiladas and asked, “Well. The pin wasn’t set, right?” Victor looked up from his plate and said, “I ask the man, ’Did he die?’ It was a stupid question. He got launched very far.” Linda’s mother, who was sitting at the end of the table, added, “Do you remember the guy who died on the human cannonball? I saw it! I was there. He died right in front of the audience.”

THIS SPRING, AFTER WINTERING IN Sarasota, where they entertain in the off months, Victor drove the blue bus back to a tiny farming community south of San Antonio called Von Ormy, where the Flores children were raised. The familiar gravel road wound past fields where rusting water heaters and shredded tires were adorned with corsages of tiny wildflowers. When the family arrived at their house, they found the property in serious disrepair. Raccoons had torn out some wall insulation, the roof was leaking, and weeds were taking over the flower beds in front of the cement-walled home Victor had built with his own hands 26 years ago. Over the bedroom windows he had secured personalized wrought-iron bars: Tito’s had his name spelled out, Frances’ was shaped like a peace sign, the master bedroom had “I (HEART) U,” and Vicky’s (the first daughter, who married a Colombian circus man with whom she works in a large touring troupe) was shaped like a V into which a set of coin-size rings dangled.

When I arrived, Victor was inspecting the roof. He is a modest, handsome, physically fit man of 57 who usually has his hands on his hips. He has glowing chestnut-colored skin and thick silver hair that he wears slicked back in evenly combed lines. He rarely speaks; he is always working. They are all always working. On this particular day, Linda, 55, was sitting at a sewing machine in the kitchen, tugging at the thread on Frances’ gold size-3 belly-dancing costume. Linda wore a pink cotton top and matching pants that brought out the pink in her fair cheeks and her painted toenails. Frances was hand-stitching sequins onto a costume with red flames, her dark hair woven into two braids that hung loosely without fasteners. Neighborhood roosters crowed all afternoon.

Frances looked through the back window at the practice ring encircled by tires. She said, “I was telling Vicky the other day, ’Man we were wild growing up in San Antonio,’ and she goes, ’No we weren’t,’ and I go, ’Yeah, we were. We were all barefoot all the time, and if we wanted to get on a horse, we’d just run over and jump on, bareback. We were fearless.’”

They had the renegade gene, but Linda and Victor were careful not to make the mistakes that past generations had made. They were strict with their children: no dating, no swearing. Every weekday that they were in Von Ormy, Vicky, Tito, and Frances would walk down the long dirt road and pick up a bus that took them to school in San Antonio. In high school they attended an alternative academy for students with special needs where they were allowed flexible classroom hours. They did homework on the road and were tested back at school. Classmates never saw them enough to befriend them; teachers never got close. One day a teacher called Linda for a meeting and told her that Vicky had a vivid imagination. “She thinks you’re in a circus,” she said. “She thinks she does a trapeze act.”

One night in Von Ormy, as the grasshoppers and roosters chattered, Victor sprang open a trampoline and called for Frances to climb on. “Frances, I want you to try to go on your stomach, then forward roll with a twist.” He laughed and patted the elastic. Frances looked unenthusiastic. “Ugh. Really?” she asked as she bounded over the springs. “Yes,” Victor said. She tried it a few times and screwed up, groaning with frustration as she belly-flopped onto the trampoline. Eventually, when the sound of the grasshoppers swelled, Frances covered her face and began to laugh. “How disappointed will you be if I don’t learn this tonight?” she asked. Victor’s expression didn’t change. “I know you can do this, Frances,” he said. “Come.” He whirled his right index finger in circles. Frances sighed and jumped with her hands on her hips. Then she concentrated, held onto a deep breath, lifted her eyes toward the sky, and did it.

When Tito was visiting the Von Ormy house one day, the subject of the upcoming Shrine Circus in Pontiac, Michigan, arose. A huge smile spread across Victor’s face. “Let us show her the trick, Frances,” he said. He headed for the front yard, where he had strung a high wire between a short metal pole and the top of a live oak tree. A motorcycle with grooved rims sat on the wire, secured by two buckles. Victor tugged on the cables that held the rigging in place, then climbed the pole and straddled the motorcycle. Frances hopped on a trapeze bar that was suspended from the pedals. Victor started the cycle, and they raced up to the top of the tree, paused, and coasted backward toward the metal pole. Frances’ weight on the trapeze kept the motorcycle upright. Her hair flew in her face as she leaned back, pointed her toes, and closed her eyes. When they stopped, she sat up straight and looked at me. “See? Easy, right? Want to try it?” she asked. “Go ahead,” Victor shouted above the noise of the engine. I took off my flip-flops and tiptoed over, careful to avoid the stray nails lying in the dirt. I jumped on the trapeze and was surprised by how heavy I suddenly felt, having all my weight on a bar the width of a shower curtain rod. Victor yelled, “Ready?” I extended my arms and legs, pushed my center of weight back, and pointed my toes, trying to imitate Frances’ pose to control the trapeze and counterbalance the weight of Victor and the bike as he drove halfway up the wire and paused. The bike’s metal wheels made a slapping noise against the cable as we slipped back to the starting point. “All right?” he hollered. He sped up to the trunk of the tree, so close I could touch the bark with my toes. “See?” Frances said, smiling as the bike coasted back to the starting position.

We traded places. “Okay,” she said, “now all you have to do is arch your back and do this,” motioning with an extended arm toward an imaginary audience, “then this.” Frances flipped upside down, hanging from her knees. “I normally do the splits, but you can bend one knee instead, like this.” She demonstrated the “stag” pose, then pulled herself back up and sat on the bar. “The only other part is the end, then. Okay?” I nodded. “Hit the high end of the wire and jump up like this, standing up, then hold on to the side bars of the trapeze. When Victor whistles, shift all your weight to the right and quickly push onto your left foot as hard as you can so you and the bike flip over the wire. You do that twice, then sit back on the bar and you’re done.”

Linda noticed that my expression had changed at the word “flip,” and she began laughing. “They didn’t tell you that part before, did they?” she said. Victor yelled over the motorcycle’s roar, “Is very easy.” Frances agreed: “It really is. It’s totally safe.” Victor nodded at me. “You okay to do it? If not, you do not have to do it. Is very easy, though.” I got back on the bar. After I went upside down into a half-split, I pulled myself back up. Tito had finished eating and came outside to tie my ankle to the trapeze. “One thing,” Tito said. “The most important thing is to keep your feet on the bar. Don’t decide not to do the trick halfway through. That’s the biggest mistake people make, okay?”

Tito was visibly nervous, shrugging and tugging at his lips. Frances looked at him sideways. Victor pretended not to notice. Instead, he leaned to the right and the trapeze rocked to the left. The wire creaked like some ancient torture device. Then he shouted, “Ready?” I yelped and somehow the motorcycle and trapeze began to spin counterclockwise around the wire without falling off. The front yard spun upside down slowly before my eyes, then sideways, while Frances shouted, “Lean left! Now right! Center! I said center!” For the two seconds when Victor and I were passing through the upside down position, the centrifugal force weakened, and I felt stuck and helpless, like a dog on its back. “You’re not centering; push all your weight down! Squat! Dad, she’s not squatting!” When I was right-side up and we came to a stop, Frances and Tito looked at each other and buckled over laughing. Tito grabbed Frances’ arm and looked up at me. “Nice face,” he said.

I wobbled back to a bench. Victor smiled and clapped twice. “Ha! That’s good,” he said. “You did a very good job. I am proud of you.” Frances and her dad continued to practice a few more runs as the torn skin on the backs of my legs began to protest a stinging burn. I looked out to the road, where a man was slowing his car down to stare out his window. His jaw was hanging down so far he could have swallowed the Floreses mailbox. “We get a lot of that,” Linda said.

CIRCUS ACTIVITY IN AMERICA PEAKED between 1890 and 1920. Dozens of troupes of all sizes roamed the country. More than 15 million Americans purchased tickets for circus performances each year. Big-top shows divided and recombined and poured through all the little towns until they were stepping on each others’ turf, wallpapering towns with posters and tearing down the notices of their competitors.

Linda’s mother, Frances Stokes, was born in 1925 into the Honest Bill Circus, and her family soon took up with the Christy Brothers Circus, which was known for grifting and gambling and, according to one newspaper, “some girls with oriental fantastic gesticulations that were inclined to make one sit up and take notice.” Frances Stokes’ mother, Fay, had brown eyes and olive skin, smoked three packs of cigarettes a day, and first married when she was fourteen years old. She was so offended by cussing that the one time she heard her daughter, then an adult, say the word “damn,” she slapped her in the face. Frances’ father, Blonda, was a blue-eyed rodeo man and bear wrestler who drank whiskey and smoked cigars. He was a severe character. Once, when he was drinking in a tavern, a man stabbed him; he turned around and bit the man’s ear off. “My very first memory,” said Frances Stokes, now 77 years old, “is riding along while I was still in bed, and I looked out the window where the men dressed in worn-out suits were all tearing down a tent. When we were leaving town, we could smell bacon sizzling in the towners’ kitchens.”

George Christy, the show’s producer, ran out of money during the Great Depression. One day he gathered the loyal performers, cooks, and workers on the twenty-car rail train for a last-minute announcement: “Beaumont coming up. Anybody who wants to get off, this is your chance.” He didn’t stop the train—he slowed down just enough so that the families could jump off and roll with all their bags they had managed to grab. Frances’ grandparents jumped. Beaumont became an odd town for a while afterward. The dogcatchers and waitresses and city workers had a strange look about them; they were leftover giants, dwarfs, odd-looking twins, muscular men and women, ridiculously attempting to blend in, hoping for brighter days, when they could quit pretending to be towners. For some of them, brighter days never came.

Frances Stokes lived with her grandparents in Beaumont and grew into a blond, stocky woman with small, glassy blue eyes and her father’s tough sneer. When she was old enough, she learned fancy rope spinning and practiced doing a contortion routine while balancing a glass of water on her head. A few years passed, and as the country recovered, the circus talent tore off their towner uniforms and lined up with different troupes. Though Fay forbade Frances to date, she arranged for her to meet a fellow circus performer’s son, George Dixon “Dick” Loter. They kissed in a car in San Antonio. Frances married him, and for a decade afterward, the Loters were based in Hugo, Oklahoma, on the Tex Carson Circus.

The family scraped by. “Step right up,” Frances would announce as Dick played bongos for the hootchie-kootchie girls. Sometimes Frances would stand perfectly still while Dick threw knives within an inch of her body. At other times he ran a sideshow exhibit of fake amphetamines and other drugs. Frances bore seven children who lived on the bus and learned to work the shows at young ages. Independence from a big-top show was an unrealistic option in those days; one needed to impress audiences with freaks and large animals, which a big top on a railroad circuit could supply.

Over the decades since Frances Stokes Loter was born—the Depression, world wars—the world shrank. People became more sophisticated. Circuses became passé. Some disbanded; others merged to stay afloat. Five of Frances’ seven children dropped out of the business, reappearing in tents once in a while to sell novelties and concessions. The only other circus Loter remaining today, besides Victor Flores’ wife, Linda, is Linda’s brother Barnum, who travels with a Houston-based show called Circus Valentine. Frances Loter barely recognizes most of the big shows anymore. Frequently, she will tell people with aloofness, “Circuses have just about quit being circuses. They’re more like magic acts than the mud shows I used to know.”

Recently, Frances Loter left her trailer in Hugo to travel a little while with the Fearless Flores Circus and Thrill Show. She arrived in the tent dressed in a long animal-print skirt and a beige cotton top. Her hair lay on her shoulders in powder-white curls, and she had touched up her lips with orange gloss. She wore light perfume and an expression similar to the stiff face exhibited by women in pioneer photos. But there was pride in her gaze and posture as she scanned the ring. The event organizer, on this particular day, was a balding man who appeared confused about his role in the activities, and VIP ticket holders were sneaking into the tent early. Frances grew irritated enough to hike up her skirt, stride over to him, and set him straight: “We need to have someone at the door so these big shots stay out of the tent.” The man gave her an impatient smile and explained, “I’m doing the best I can.” Frances turned around, rolling her eyes: “Well, what do I know? I’ve only been doing this for seventy years.”

OUTSIDE A CIRCUS TENT NORTH of downtown Dallas a few months ago, a storm was brewing. A roar unfolded and rolled across the sky. A producer had supplied a big-top tent for a fair and hired the Floreses to arrange a one-ring show. This particular date required a gymnastic ring act—the specialty of Tito’s wife, Chela—and so the second Flores unit joined Frances, Victor, and Linda in the tent along with a few of Linda’s brothers and sisters, who set up concession and souvenir stands. (Though Chela was pregnant and entering her second trimester, she assured me the rings were not a problem.) Since Frances was going to be performing many of the other routines herself, including the trapeze, the Globe of Death, and the trained pigeons, she had planned on wearing different wigs for each act, and she invented various pseudonyms under which she would perform. She scribbled some notes on the lineup sheet near the microphone. “Hey, kid! What’s your girlfriend’s name? Amber? Amber—what do you think? Amber?” she asked, drumming a ballpoint pen on a card table. Then she changed her mind: “No. I’ll be—Elizabeth!” She was heading back to the bus to put on her first wig when the ring announcer, dressed in a red-and-white-striped suit, reported, “Ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, a tornado had been sighted in the area. We’re going to have to postpone the show for thirty minutes.” The visitors were evacuated to a nearby building, grumbling all the way. As the lights were turned off, the Loter clan swapped stories about legendary storms that had wiped out circuses. For the next half-hour the Floreses and the Loters huddled in the leaky tent while a terrifying wind and sheets of rain batted against the canvas that shrouded them in complete darkness.

Victor never could have foreseen moments like these when he was a boy in Mexico. Growing up in Tabasco and Puebla, he had no desire to be a performer. His father was a wholesale meat provider for restaurants and later ran a restaurant himself, and he and his Italian wife encouraged young Victor to go to college. “Be a businessman,” they told him. Victor set out in accord with his parents’ wishes. He got a degree in business. But he had a wild side. In high school he and his neighborhood friends watched The Wild One, bought choppers, and formed a motorcycle club. One day, when he was in college, a friend asked him if he wanted to do motorcycle tricks in a show. After three years with Mexico City circuses, he came to the United States, his belongings packed in a cardboard box, to perform clowning, flying trapeze, and high-wire acts for the big-top Carson and Barnes Circus. It was there that he met Linda Loter.

She was spinning high up in the air on a rope when he spotted her, a fair-haired Barbie-doll beauty. At the end of the show, Victor made sure he was standing next to her so he could hold her hand as the group took their bows. She had a sharp wit and a sarcastic sense of humor. Her childhood had hardened most of the softness in her; she had been the designated “boy,” helping Dick Loter with the mechanical equipment and heavy lifting. In the ring, she performed aerial acts, but she preferred to work with her ponies and dogs. She tended to laugh long and hard until the sound turned into a mischievous chuckle in the back of her throat and her pale, round face blushed bright red. Linda saw that Victor was earnest and smart and handsome, but she married him because of the way he looked at her.

When their kids were young the family traveled with Carson and Barnes, just as Linda’s forebears had traveled with the touring outfits in their day. It wasn’t until the eighties that Victor decided to get ambitious. Freak shows had become extinct, and the giant and dwarf who had been witnesses at Victor and Linda’s wedding had to get jobs behind the curtains; People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals was railing against circuses’ use of animals, and government inspections had become more restrictive. Death-defying human tricks were the wave of the future. For this, the Floreses would be prepared.

One of Victor’s circus bosses wanted him to learn the Globe of Death, which the man had seen in Mexico City. So Victor went down to Mexico and had a globe custom-built, then he hired a man to teach him the trick over the course of a year back in the United States. Victor learned to ride the globe on a bicycle. In a few months his legs were as bulky as bags of mangoes. Once he was familiar enough with the feel of the bicycle in the globe, he switched to the motorcycle and taught eight-year-old Tito. Victor stood in the middle of the globe and held onto Tito’s shirt as he circled around him. When Tito got too high and fell, Victor caught Tito and the bike. When Tito had the Globe of Death down pat, he taught his older sister, Vicky. Once Vicky was riding, Victor taught Frances—the wildest of the children—and in 1987 they were introduced in the ring as the Fearless Flores Family.

Over the next few years, Victor decided to take a bigger risk. He had seen the direction circuses were taking. In a short period of time, he acquired a set of gymnastic rings, a trapeze, a human cannonball gun, a space wheel, one of four breakaway sway poles in the country, a tent, a truck, a canvas backdrop, and a sound system. He arranged dates for the family as an independent show, performing at carnivals and fairs. They would do a few short dangerous tricks. He made phone calls and kept lists. He did the math to make sure each trip was worth his family’s while. They were disciplined; they lived simply. They shopped at Wal-Mart. They wasted no food, creating soups out of leftovers. In the summertime, instead of turning on an air conditioner, they kept the doors wide open. In the wintertime, they heated the house by using two fireplaces. Victor began to teach Frances and Tito his rules of business: Be straight with people, never mix friendship with business, and never mix family matters in business. Their reputation grew; the investment was paying off. And gradually they began to get ahead.

The storm calmed as quickly as it had developed and at the half-hour mark—just as promised—the show went on. Tito, dressed in black jeans, stepped up to the microphone on the south side of the ring, out of the spotlights. He began his preparation announcements and looked at the sheet onto which Frances had scribbled her pseudonyms. “On the aerial trapeze, please welcome,” he said, glancing down, “Eee-lizabeth!” Frances, wearing a black wig, high heels, two pairs of tan tights (one opaque, one fishnet), and a red satin two-piece costume, pranced into the center ring and vamped. Tito cued threatening synthesizer music. Frances slipped out of her shoes and crawled up a rope, then sat on the trapeze, flipped upside down, and began to strike about two dozen poses. One woman in front of me whispered to her friend, “This is just like the Puerto Rican circus,” and they both nodded happily. Frances posed some more, sat up, and then began to swing, and in one motion she wound the side trapeze cords around her ankles and slid upside down. The crowd was quiet. In a matter of seconds, she pulled herself up, slid down the rope, and posed with her chin up, her arms above her head, her fingers spread, her feet in a balletic third position. “Please give her a warm round of applause, ladies and gentlemen,” Tito said. “Elizabeth!”

After a few more acts—a freelance foot juggler, a clown and balloon act, and “Miss Linda and Her Terrific Terriers!” in which roughly a dozen shivering, wide-eyed rat terriers wearing ruffles around their necks jumped through hoops, danced, crossed high wires, dove off platforms, and slid down slides to the tune of “Sweet Georgia Brown”—Chela sauntered to the center of the ring, her two-and-a-half-foot-long hair wrapped up in a bun surrounded by silk flowers. Dressed in a white-and-beige-sequin leotard, she swayed and flipped on the rings effortlessly. Again, the crowd applauded. She left the ring. Then Frances came out as “Miss Sendel Sebrine.” She wore a belly-dancing outfit this time, with a red veil that hid her face, and she posed while Linda opened a cage of pigeons. The pigeons, it turned out, didn’t want to perform, and so Frances improvised a belly dance. Tito waited for her choreography to lose its verve, then shouted, “Let’s hear it for Sendel!”

“And now,” Tito said, “please welcome, for your circus entertainment, the Fearless Flores in the Globe of Death!” This was the part of the show the Floreses loved. It was a stunning finish. Tito cued up dance-club music. The spotlight on the globe in the darkened tent gave the appearance of a small space and heightened danger, and when the act was finished and the Floreses pulled the motorcycles into the center ring for their bows, the crowd stood and cheered wildly.

As soon as the audience had left, the Floreses packed up their gear. The warm air had turned thick with humidity, retaining the smell of dirt washed with rain. They ate buckets of fried chicken that had been laid out in the bed of a parked pickup. Tito’s daughter danced with Frances to “You Sexy Thing” and “Respect Yourself.” Tito was joined by Bill Loter, Linda’s 45-year-old brother from Farmers Branch. For a living, he sells cotton candy and delivers cakes. He is a skinny man with wild blue eyes, a freckled and sunburned face, and small teeth strung across a wide, open smile. “Well, Tito, you did a great job in there,” he said. “This is one of the best shows I’ve seen this year, and that’s really saying a lot.”

“We had a good audience here,” Tito replied. “It’s getting harder and harder to draw people out to shows, though. People see a circus tent now and they say, ’Oh, a circus,’ and keep driving. We should have concert lights and techno music. That’s what I play for my globe act. People always compliment me on that.”

“Yep,” Bill said. “It’s just not like it used to be. It’s a dying art.” Tito nodded. “Seriously,” Bill said. “All those folks in Hugo are on oxygen tanks now; you’re the next generation. There was a time when—you know how you used to be able to get into a circus tent for free? Go in and say you were a Loter. Not anymore. The Loters are all getting out of it. Loter blood is down to a trickle.” He stared at Tito hard, almost threateningly, but Tito stood unruffled, perfectly postured. “You’re about all that’s left.”

MOST AMERICANS THESE DAYS ARE nomads. Once they pass high school age, they frequently leave the neighborhood, town, or state in which they were raised and they begin anew. Years ago, when generations of large families populated towns, circus people were considered dangerous: They weren’t tied to one spot where repercussions and responsibilities governed behavior. But the tables have turned. These days, people who were born into circus life have easily adjusted to the road, floating across the states like a roaming neighborhood, while the rest of the country separates and relocates to alien territory, uprooting once every few years to begin all over again. But there is a price to being a resident of a roaming neighborhood. One night on the road, Frances needed some privacy. She called her sister on her cell phone while sitting in the Globe of Death. After she hung up, she stayed perched on the side of the cage and invited me to come in. The metallic glow of a fairground light was just far enough away that the black metal of the globe blended with the dark blue sky. She checked the messages on her green-glowing phone to see if any of her cousins had called. Once in a while, she explained, a towner guy was charmed enough to ask her out on a date, but she knew they’d just hang out a few hours and then she’d never see him again: Circus people date circus people. “My family is dear to me,” she said, “but … my best friend is my sister, Vicky, okay? Once in a while I’ll just fly over to see her because I miss her, and we just hang out. We don’t go out. I like it.” She picked at the calluses on her hands. Her face fell and she shrugged. “I guess … you know. I’m a little lonely.”

IN PONTIAC, MICHIGAN, THIS PAST May, Frances and Victor stayed in Tito’s trailer while the trio performed at the Shrine Circus. Tito watched his wife—by this time six months pregnant—fold baby clothes while Cyndel fell asleep under the soft yellow light of the kitchenette table. Though it was eleven o’clock at night, Victor had just gotten around to eating dinner—chalupas. He balanced a plate on his knees and ate on a couch in the trailer’s shadowy living room. Frances stood in front of the bathroom mirror and brushed her hair. She was excited because the Tarzan Zerbini Circus, in which Vicky and her husband perform, was setting up on the other side of the U.S.-Canadian border that night. Frances had heard that a few of the circus guys her age were going to hit the Canadian casinos, and she wanted to be ready in case they called and offered her a ride.It had been a long week. The family had been performing the Globe of Death and the high-wire motorcycle acts several times a day for a huge, five-ring show in the Silverdome, alongside other group and solo acts, which included two flying trapezes, tigers, elephants, ponies, horses, chimps, baboons, sway poles, magicians, a high wire, three Globes of Death, a space wheel, a human cannonball, and a man who doused himself in a flammable liquid, lit himself on fire, and jumped off a fifty-foot pole. To give the $10-a-head show more pizzazz, the Shriners gave it a modish title: Circus Xtreme.

At the Shrine date, the Floreses were able to chat with other performers between acts, after shows, in the dressing room hallway (which smelled, at various times, like elephant dung, cotton candy, and sweat on metal), and during an elephant keeper’s sixteenth-birthday party, a potluck cookout held in the elephant barn. Almost all of the performers spoke both English and Spanish, even though only half of them were Hispanic. Most of them worked for bigger circuses. Everyone asked questions about who had been traveling with what circus and where they had purchased equipment; they flattered each other’s children, each other’s performances, each other’s homemade outfits. Victor didn’t say much to anyone. He picked up a hamburger and quietly ate in a chair, seeming as content as the elephants that were snorting and swaying in beds of hay five feet away.

Earlier in the day Tito and I had sat in the stands during a lightly attended matinee show. He told me that his dad has passed the baton to him, teaching him how to produce the Fearless Flores Thrill Show at fairgrounds. Soon he would learn to produce even bigger events. “Next year, that’s my goal,” he told me. “To produce a Shrine date. In two years I’d like to have that going all the time, then my dad wouldn’t have to perform if he didn’t want to. Of course, I’d still perform. I mean,” he paused to find the words. He started to laugh, his hands on his chest. “I’d perform if I won the lottery. Okay?”

That night, back in the trailer, his confident half-squint had softened from exhaustion, and he stroked Chela’s arm. He began to talk about what it might take to get by and wondered about the risks of getting ahead. “I want to be consistently good,” he said, “not inconsistent and risky. Fame is not worth it to me.”

Frances yelled from the bathroom, “It is to me.”

“Right,” Tito said gently, with a shrug. “It is to Frances.”

She walked into the living room of the trailer, gesturing with the hairbrush as she got serious, and said, “I want to be the old woman who walks into a show and everyone turns around and says,’That’s Frances. She used to do this and this.’ I work hard. Shouldn’t I let people know it? I want the glory.” Tito looked at her affectionately, and she began to laugh. “Well?” she said. Then she walked back to the bathroom. Victor and Chela said nothing.

“All I want to do is support my family,” Tito said. He thought about it, then he grabbed the table and a smile opened on his face. “No. All I want is a dynasty. Is that too much to ask?”