At least on the surface of things, it would seem that Wes Anderson should be celebrated as a true homegrown hero. He was born and raised in Houston, where he attended St. John’s School. He famously collaborated with his University of Texas classmate Owen Wilson and Wilson’s brother Luke on Bottle Rocket (1996)—the movie that launched all their careers. His second feature, 1998’s Rushmore (which was shot mostly at St. John’s), earned considerable praise from critics, some of whom envisioned Anderson as the most original comic filmmaker of his generation. By his third movie, The Royal Tenenbaums (2001), the director had also established a devoted cult following, especially among college students and boho types. And even though he has since traveled far beyond the borders of Texas, he’s done so in an ambitious, globe-trotting manner that should only make us proud to call him our own: His fourth film, The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou (2004), was shot at Rome’s Cinecittà Studios, where Fellini made many of his famous works; his latest effort, The Darjeeling Limited (opening in limited release this month), follows three oddball brothers—played by Owen Wilson, Adrien Brody, and Jason Schwartzman—on an elaborate journey across India.

And yet this portrait leaves out one crucial detail: namely, that Wes Anderson is also responsible for perhaps the most dispiriting trend in entertainment today—the run-amok hipsterism that currently saturates our airwaves and multiplexes. With his self-consciously “stupid” jokes; his alt-rock, emo-ish taste in music; and his mannered, hyperstylized images, the filmmaker has certainly created a distinct style—and a bizarrely influential one. You see his fingerprints in movies (Napoleon Dynamite, Garden State), on television (Flight of the Conchords, Arrested Development), and even in Gen Y literary fiction (Joshua Ferris’s Then We Came to the End, Miranda July’s No One Belongs Here More Than You). But the cumulative effect of all this glibness is proving exhausting, not to mention depressing. The über-postmodern aesthetic that Anderson pioneered now threatens to drown out any remaining hints of sincerity in our popular culture altogether.

This is hardly a turn of events you might have predicted watching Bottle Rocket, a caper comedy so loosey-goosey and low-key that it seemed forever on the verge of grabbing a blanket and taking a nap. But Rushmore—about an alienated prep school student named Max (Schwartzman) and his friendship with a lonely millionaire (Bill Murray)—hinted at an idiosyncratic comic temperament, at once ingenious and strangely off-putting; here was a filmmaker who used artifice as a means of never having to dirty his hands with real emotion. With each frame more artfully composed than the next (remember the staccato montage of Max’s extracurricular activities, from fencing to beekeeping to the Max Fischer Players theater troupe?), Rushmore generates its laughs by way of props, costumes, camera placement, and lighting—the stuff film nerds call mise-en-scène. Yet at the center of this lush design are holograms instead of real people; manufactured poses in lieu of recognizable feelings. Anderson deepened his style in The Royal Tenenbaums, about three erstwhile child prodigies (Gwyneth Paltrow, Ben Stiller, and Luke Wilson) who must finally come to terms with their ne’er-do-well, absentee father (Gene Hackman). The movie is gorgeously photographed, in burnished candy colors, with the actors starkly at the center of almost every frame. But each time Anderson strives for deeper resonance—the scene, for instance, where the suicidal Margot (Paltrow) leaves her clueless husband (Murray, again)—the director can’t help but clutter the proceedings with gratingly twee flourishes. How else to explain the fact that, during this supposedly heartfelt sequence, the Vince Guaraldi Trio’s “Christmas Time Is Here,” from the classic Peanuts cartoon A Charlie Brown Christmas, is playing on the sound track?

That’s the rub of Anderson’s works: They seem to exist less as movies than as monuments to the director’s own “refined” and “smart” taste. He strains to collect the “coolest” actors (the perpetually blank-faced Murray turns up yet again in The Life Aquatic), the “coolest” music (the Tenenbaums sound track alone features Bob Dylan, Nico, the Clash, Paul Simon, and Elliott Smith), the “coolest” references to other movies (much of Rushmore plays like a hymn to the geek-chic classic Harold and Maude). It’s like hanging out with your most annoying, name-droppy friend, who insists on reminding you, every fifteen minutes, that his life is way more enviable than yours. (This cool factor also might explain why Anderson hasn’t worked in Texas since Rushmore; why hang around at home when you can impress your friends with far-flung postcards from Rome and Bombay?) And while Anderson is hardly the only young American filmmaker these days who allows technique to triumph over storytelling (see Todd Haynes’s Far From Heaven and David Fincher’s Zodiac) or ironic detachment to obliterate character development (see Spike Jonze’s Adaptation and David O. Russell’s I Heart Huckabees), in many respects his efforts feel the most obnoxious of all. Just try watching The Life Aquatic, with its matrix of impenetrable references to Jacques Cousteau, the French New Wave, and Owen Wilson’s penis size, and see how many minutes elapse before you want to hurl a brick at the screen.

As of late August, The Darjeeling Limited still wasn’t ready to be screened for critics—so perhaps there is hope that Anderson will strike out in an entirely new direction; he’s got too much evident talent and potential for us not to keep rooting for him. (Indeed, any filmmaker capable of getting an understated performance out of Ben Stiller—whose turn as a tightly wound financial magnate is the funniest and most affecting thing in Tenenbaums—is clearly some kind of genius.) For now, though, it’s impossible not to brood. The widespread exaltation of Anderson’s arch sensibility has only served to marginalize the more earnest young American comic voices working today, such as the wonderful Nicole Holofcener (Friends With Money, Lovely and Amazing). With just one recent exception—Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris’s Little Miss Sunshine—the old-fashioned approach of Charlie Chaplin, Frank Capra, and Preston Sturges, and their stories about the touching foibles of lovable underdog heroes, is an increasingly endangered species.

Anderson may never have set out to do any lasting damage to the American comedy tradition—or, for that matter, to inspire legions of artists to ape him. But that still doesn’t let him off the hook.

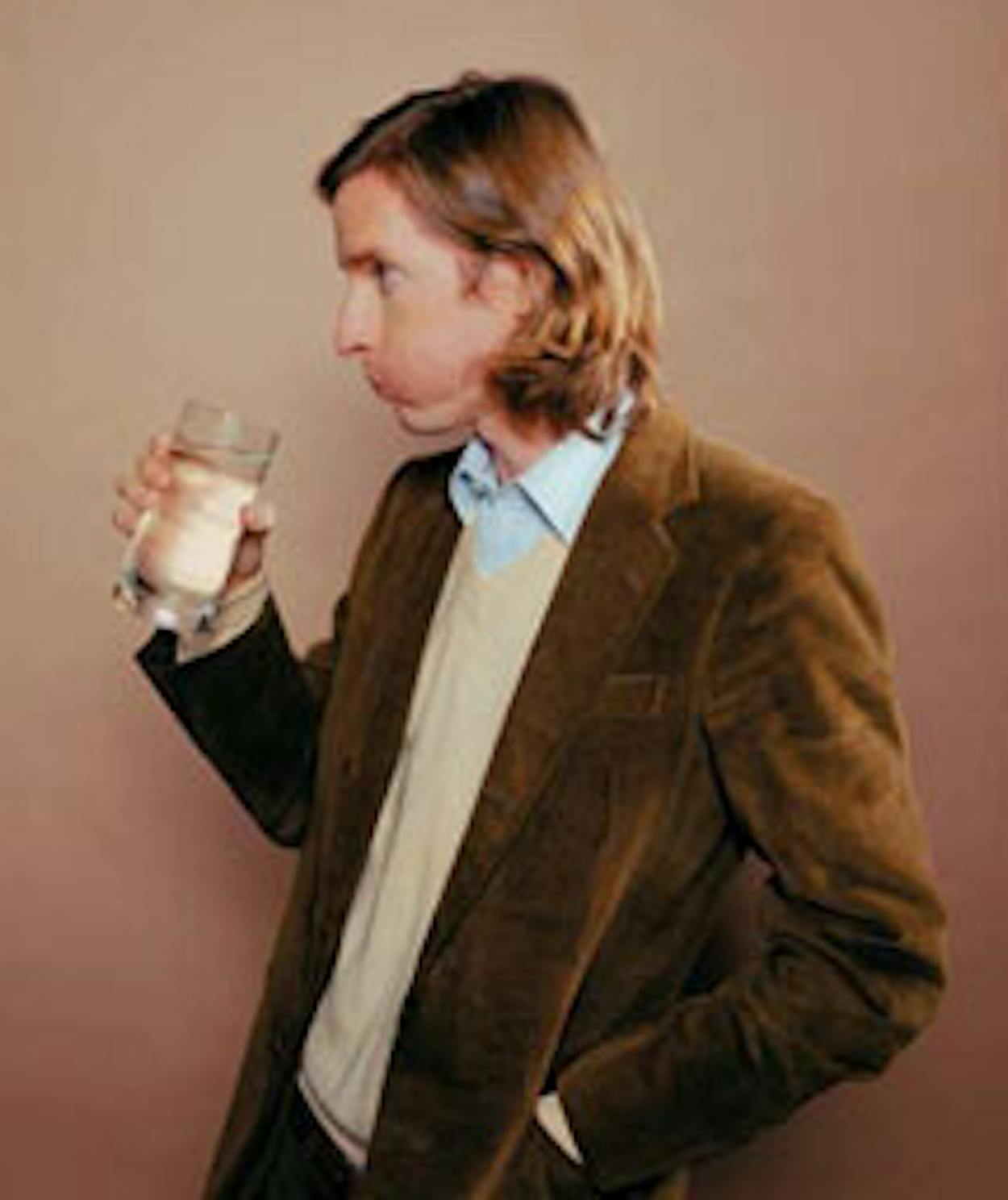

My Life. My Art: The hipster auteur in two minutes flat.

If you want to get an instant sense of everything that’s wrong with the Wes Anderson oeuvre, log on to YouTube and take a look at the director’s 2006 American Express commercial. Part of the “My Life. My Card” series (M. Night Shyamalan and Martin Scorsese also directed spots), it begins on a film set, with Anderson directing a white-suited Jason Schwartzman. Anderson then begins wandering around the set, giving viewers a miniprimer on how films get made, all the while getting distracted by assorted crew people. The style is affected (the clip unfolds mostly in one fluid take), the references are precious (the musical score used here is from François Truffaut’s famous movie about moviemaking, Day for Night), and the quirkiness factor is through the roof (for some reason, there’s a geisha getting her makeup done on set). Anderson may have aimed to poke fun at himself, but the effect is the opposite: This commercial plays like the most obnoxiously self-aggrandizing celebration of Anderson’s “coolness” imaginable.