This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

In Baytown, on the Texas coast, they have torchlight parades before big games and snake-dance down Main Street like carnival-goers in Rio, at once affirming and celebrating their faith in the Sterling High School Rangers, four times district champions. In the parish halls of the more sedate but no less successful Highland Park district of Dallas they hold candlelight vigils and pregame suppers, while out in Brownwood they have 4-H Club fairs and special livestock auctions to benefit the team. In Houston’s Spring Branch suburb the students stencil bearclaws all over shopping center parking lots to remind the faithful that THE BEARS ARE COMING, and on San Antonio’s West Side there are neighborhood fiestas with football-shaped piñatas and fireworks.

For whole communities, football offers the surest way to dazzle the neighbors. Especially in rural areas, where dramatic opportunities are fewer, there is no grander way to prove the collective mettle than to win a high school football game. Places like Port Neches–Groves, Nederland, or Hull-Daisetta can easily escape the notice of Rand McNally, but in Texas they are powers to be reckoned with a thousand miles away, to be denounced by distant boosters and politicians, spied on and worried about. For many Texans, football provides the clearest measure of a Texas community’s vitality, self-pride, and sense of identity, and no one is more aware of this than the men most involved with the life of the town.

Each week in the fall, along about Monday or Tuesday afternoon—when the Friday-night football passions are at their lowest ebb in the town at large—certain earnest and farsighted men in a Texas community gather in the rear of a town square coffee shop or a barbecue parlor, maybe in the VFW hall or the bank boardroom. If the local high school is especially rural and small, or its football team is undistinguished, they will likely meet unobtrusively, in the coach’s office perhaps, and talk over old times and declining prospects. However, if the school is large or suburban, or if a promising season is underway, they might well take over the Regency Room at the Holiday Inn and have themselves a regular luncheon, watch game films, and listen to lectures by assistant coaches. The scope of the gatherings varies across the state, in keeping with local tradition and the team’s current fortunes, but by suppertime on Tuesday some one thousand such meetings will have been held in the towns and neighborhoods of Texas, among men concerned with the worth of those places.

In their other roles, they might be deacons and county grand jurors, precinct judges, trustees of the soil conservation board and 4-H Club sponsors, men with responsible habits and a broad sense of citizenship. Generous with their time and money and fervid as a result, they devote themselves six months a year to advancing the interests of the local high school football team. Calling themselves the Bobcat Boosters or the Bay City Quarterback Club, they organize caravans to out-of-town games, welcoming committees for home games, team banquets with guest speakers; they pay for tutors for dull players or surgeons for injured ones, for various kinds of fancy equipment—pro-style Riddell helmets, say, or sideline headphones for the coaching staff—things the local school board can’t find any way to finance or justify.

The boosters mount campaigns to search for a new head coach if they think it’s time, to lobby with the school board or league officials when needed, to sell season tickets or ads in the game program. In the old days they also used to help with the covert recruitment of exceptional thirteen-year-olds, but this got so out of hand after Texans got rich—the classic story is the oil company that was purchased so Sammy Baugh’s daddy could be transferred to Sweetwater—that the state Interscholastic League finally cracked down in the late fifties. Nowadays the booster clubs are all chartered and regulated, required to have bylaws and certain officers, and occasionally have sanctions imposed in a manner that league officials consider to have ended the more outrageous cases of booster club zeal.

The devotion to football is a social sentiment shared all over Texas, in each of its ethnic and geographic enclaves, across all of its classes. The two most elite public high schools in the state—Highland Park in Dallas and Lamar in Houston—have been on-and-off football powers throughout their histories, fielding teams made up largely of oilmen’s sons, lavishly boosted and cheered in style, just as excited as anyone else. For years they would meet in the state eliminations with teams from the oil boom towns of West Texas—places like Abilene, Stamford, Wichita Falls—teams composed of roughnecks’ sons and, often as not, of roughnecks themselves. The oil-belt towns were notorious for their twenty-year-old seniors and their eligibility hassles, for their giant linemen and windswept fields, for beating up referees who weren’t quick to leave. They dominated Texas schoolboy football during the forties and fifties, the years between the discovery of oil and the integration of the schools.

Texas blacks had always competed in a league formed among their own schools, separate and unequal in every measurable way, short on uniforms and travel budgets but equally devoted to the native passion. In the sixties Beaumont’s Soul Bowl could prompt a week of riotous amenities and draw 20,000 fans to a borrowed college stadium for the crosstown meeting of the Charlton-Pollard Cougars and the Hebert Panthers, both teams that had sent numerous alumni to the pros—Bubba Smith’s daddy was the Cougars’ coach—and both with statewide followings. Scouts from a hundred Yankee colleges would come in for the game; those were the days when foreign conferences like the Big Ten built national football reputations by recruiting Southern blacks, especially Texans. Most collegiate teams in Texas weren’t very noticeably integrated until the early seventies, nearly a decade after the high schools had managed it.

The success of Texas school integration was guaranteed on the Friday evening in 1962 when San Antonio’s polyglot Brackenridge Eagles took the state Class 4A championship—the highest classification—with a sidearm-throwing Mexican American quarterback and a soon-to-be-famous black running back named Warren McVea. Within five years the balance of prowess had shifted from the oil belt to East Texas, where there were blacks enough to make integration meaningful, difficult, and potentially divisive. As many saw it, football was the only thing that made it worthwhile.

The booster clubs were generally where it started: meetings between black and white counterparts, trading hopes and scouting reports, telling the old stories to receptive new ears, sharing their passion. Most of the better restaurants and Holiday Inns of East Texas were first integrated by the local high school football booster club. The rest was inevitable: Texas high school football was a stronger tradition than segregation, broader in spirit and more fun to watch, too innocent for prejudice.

By Wednesday morning all the boosters have signs up in front of their homes, cardboard cheers and admonitions for the upcoming game—LASSO THE MUSTANGS—hand-lettered in the school colors. Retail merchants put out placards and allow their windows to be luridly painted, businessmen pointedly display their booster club sponsor certificates, and team rosters are taped up in restaurants and other meeting places, like the names of favorite sons.

The approaching cares of Friday grow large in many female minds as well, from budding majorettes to mothers and wives, bringing the same sense of purpose and urgency into their lives. Banded together as the Boosters’ Helpers or the Bobcat Moms, or in more genteel parts as the Junior League, the community’s women support its sons with as much assurance as its men encourage them. They hold bake sales to buy team blazers or send the band on trips, they dote on the new coach’s wife to make her feel at home.

By Thursday afternoon nearly everyone has something to practice or plan for, or at the very least to mull over. The local high school’s entire line of extracurricular pursuits—the marching band, the student government, the drill team, pep squad, honor guard, baton twirlers, mascot handlers, cheerleaders—all are rehearsing their parts, substantial or not, in the elaborate ceremony that the game inspires. Talk among fans grows more single-minded by the hour, and generally louder; telephones are kept busy. If the game is to be played out of town, someone reliable is dispatched to paint all the railroad trestles between home and the rival town, and caravans are organized; cars are cleaned up and decorated, dresses are examined, chrysanthemums refrigerated.

If the game is considered important, a public pep rally is held on the square in rural towns, at a neighborhood park in urban areas—either Thursday night or Friday afternoon, possibly both, depending on whether the game is at home or away. The school band plays and the cheerleaders lead cheers; various local politicians, along with the head of the booster club, the school principal, and a minister or two, make speeches; then the team is introduced and the coach says a few tongue-tied, embarrassed words. Everyone joins in singing the school fight song. The crowd cheers at every cue and every opportunity, expressing their support by the fact of their appearance, rewarded by their sense of belonging. At no other point in the year, in most small towns, will as many people gather as appear for a high school football rally. Thus Friday’s business will be excellent in towns where games are to be played, the best all week long for restaurants and motels, most stores, for gas stations and liquor stores.

In the visiting team’s hometown, a kind of mobilization occurs. For a crucial game, the booster club may coerce the city council and the chamber of commerce into calling half-day holidays, and stores and offices will close by noon to let everyone get ready. Schools may let out early so the various supporting casts can go home to get uniformed, find their instruments and pom-poms, and return in time to board the buses. Cars and pickups run around on last-minute errands, collecting dates and families, gassing up, heading eventually toward the town square, where one of the boosters is keeping a list of vehicles and passengers to insure that everyone arrives together and safely. Girls and women visit between cars to confer on postgame plans, men boast and reminisce and ice down beer, children pass out streamers.

Squad cars arrive to lead the procession—local policemen or sheriffs, highway patrolmen if county lines must be crossed, or, most prestigiously, a Texas Ranger if an off-duty volunteer can be rounded up. On an autumn Friday evening some three hundred Texas communities will migrate in this way; on stretches of the High Plains they might travel two hundred miles or more, and towns reaching the state finals will go twice that far for play-off games. Convoys of thirty or forty beribboned cars and pickups are common, often several following at intervals, honking and whooping, waving crazily at bystanders, shouting out the names of their town and team.

In the vanguard of this rowdy entourage, in a regulation school bus wrapped with banners and trailing streamers, ride the young Football Heroes on whom all are depending to uphold their honor. Notwithstanding a few brief outbursts of nervous bravado, it is a very quiet and somber bus. The prospective heroes are mostly fifteen and sixteen years old, unused to being depended upon for anything at all, justifiably haunted by the fear that they’re really just children.

Men and Boys

A sixteen-year-old football player is not, even in Texas, a natural-born Football Hero. He is merely an immature man—a volatile mixture of boyish ardor and manly dreams, still awaiting self-discovery. If in Texas more commonly than elsewhere he first tests his manhood on a football field, it is only because in Texas this gives him a clear indication of what sort of man he might be. It is a testing that all boys seek and require, by whatever standards their people most loudly applaud. So in Texas this crucial passage is often made, for better or worse, under the guidance of a high school football coach.

The first two people to perceive and abet the man within a Texas boy are the first girl who loves him and his high school coach; at least that’s how he feels at sixteen, when he is certain that no later man or woman can ever affect him as deeply again. A coach with the vision and sensitivity to live up to this role can build winning teams in the most obscure of places, year after year, from whatever boys are on hand, by making them believe they are Football Heroes. If he has the gift, he can transform a Texas town more dramatically than John Wayne: booster clubs will rise from the doldrums, school boards will cooperate and bond elections pass, crowds will begin appearing at afternoon practices. The actual winning becomes almost inevitable, at any rate predictable, as long as they all believe in their boys.

A coach who stays with the game must love it enough to live it through his boys, as dependent upon them as they are upon him; only then can he truly see them as Football Heroes instead of boys. And if he can’t believe in them, they surely won’t be able to believe in themselves. Houston Oilers head coach Bum Phillips, who had built a remarkable record as a small-town Texas high school coach before stepping up to the pros—a step that could take place only in Texas—has often said that he treats his players no differently now than he did back then, which says less about how he treats his men than it does about the way he saw his boys.

Back in the forties and early fifties, when Bum Phillips first started coaching in the Golden Triangle, many small-town high school coaches in Texas weren’t even paid a regular salary. They worked instead for a percentage of the gate, like tent-revival preachers, relying for a living on the force and success of their inspiration. Moving every few seasons to a new and slightly bigger town—or at least to a larger school—they progressed if they could from the B leagues up to the 4A ranks, where the best high school football in America is played before the biggest crowds. Indeed, up until the mid-fifties a Texas 4A championship game could draw bigger crowds than most pro teams saw in those days, and Texas schoolboy coaches were widely considered the best in the game.

Texas high school coaches have long been famous for their innovations and refinements, their trick plays and new formations. Old Pop Warner’s revolutionary single wing was first exploited by the Waco High School Tigers under his friend Paul Tyson, inventor of the spin play and the lonely end; Tyson was the coach Knute Rockne said knew more about football than anyone else in America. The Lubbock Westerners were playing from a slot T offense in the late forties, several years before the Chicago Bears overwhelmed the NFL with it, and such major modern alignments as the wishbone and the veer, the four-five defense, were all first put to use and proven by Texas schoolboys, devised by coaches who never doubted their boys were up to it.

And doubt is something the best coaches never feel. Jim Norman, head coach at Big Sandy, says: “Now I’m forty-three years old and I been in the business of coaching and teaching for nineteen years. But I can’t put my heart into teaching, only into coaching, Right here, in football, I can say, ‘Now, son, this is life. We’re gonna go out there today and this is your assignment. And if you don’t survive it today you’re gonna get fired and lose your position. But if you do survive it, you’re a starter. You’re on your way.’ That kid comes out here at two-thirty after classes. He’s tired, drowsy. I feel like if I can teach him to reach down and give me some real go-get-’em then he’s got a chance. He’s learned something he can use all his life. I teach him to keep challenging. If some kid knocks him on his butt, he can’t accept it. He’s got to learn to get up and go at him again. And again. That’s football and that’s life. I got kids come out and can’t cut it. We all have ’em. And I can tell you from experience what’ll happen to ’em. They’ll be hauling pulpwood like their daddy. Or be working all their life as a laborer. They’re gonna be satisfied to go right back to doing that. But I have other kids I can teach to challenge, to keep coming back, and they are the kids that’re gonna go somewhere.

“I remember when I was playing high school football, and I was running in the backfield, my coach called me in one day and said I was gonna have to be doin’ a little bit better if I wanted to keep my first-string position. Well, that bothered me, of course, because I was being told I needed to improve. But he did it in a way that I kept my pride and went on to improve. In the past I’d been told, ‘You can’t do that. Get over here. Let a man do that.’ You know, my daddy dealing with me as a kid. But the coach told me the situation man to man.

“Nowadays I go to a football game and you know what I think about? Gladiators. I don’t see a football game at all. I picture myself out there in a toga, and everybody’s shouting ‘Kill the bum! Kill him.’ Right here tonight, you watch what happens. These fans go crazy. And yet, it’s the one time in life for that little hometown kid that he’ll ever be known. He’ll strut out there with that jersey and helmet on like a damn racehorse coming to run. The band’s striking up and he’s ready to go. God, it’s the greatest thing in the world. He couldn’t fight his way outta a wet popcorn bag, but I guaran-damn-tee you right then he can whip anybody. His momma is up in the stands clapping and yelling for her boy, and soon as he gets a good lick he comes a-limping off showing his battle scars.

“You ask that kid why he likes the game and he says, ‘I don’t know, just like it.’ But it’s so clear, so plain to see. We all want to be out there facing the challenge for our town, for our people. We’ll never get that chance again. And if we get whipped five times in a row, we learn that you don’t necessarily get whipped six. We learn to face the challenges one at a time. I mean that kid might get hit and roll up like a nickel window shade. But he learns that if he keeps getting up he’ll be admired, he’ll be loved, he’ll be a man, by God. It’s something he may not get at home, and for sure not in the classroom.”

The Boy Hero

There are places in Texas where a boy can start playing tackle football in the fourth grade with his parents’ permission, which enough of them get to populate a league of 450 teams around the state, complete with their own playoff tournaments and nine-year-old cheerleaders. They usually adopt the local high school’s colors and mascot and gain the support of the local booster club, which regards them as a valuable farm team, so that before reaching puberty they have already grasped the game’s basic scheme and style of play: run hard, hit low, never stand still. Weighing less than a hundred pounds apiece, looking awkward in their giant shoulder pads, they practice at aggressiveness three days a week, running and hitting, only to forget it all and act like children—hesitant and fumbling—in the actual game itself, which grade school teams play on Thursday afternoon.

On Friday afternoon the junior high games are played. Boys too young for acne will be pumping iron by then and, if their parents can afford it, attending summer football camps, specialized clinics run without league approval under the name of some famous pro and staffed by off-season collegiate stars. The famous pro will occasionally visit to pep-talk the boys, often bringing a few less famous teammates who enjoy telling football fables to all those eager, still uncorrupted young believers. They invariably find it refreshing and rewarding—the men do—and proceed to hang around for days. On a separate tour another famous pro will come along to proselytize for the Fellowship of Christian Athletes, and most boys readily step forward to accept this message also. Feeling bold in the company of professional heroes, and instructed by only slightly less professional college heroes, the boys attack blocking sleds and tackling dummies with startling zeal, they do endless sit-ups and wind sprints, they work on impressing each other with fables of their own. They begin to think of themselves, too, as Football Heroes.

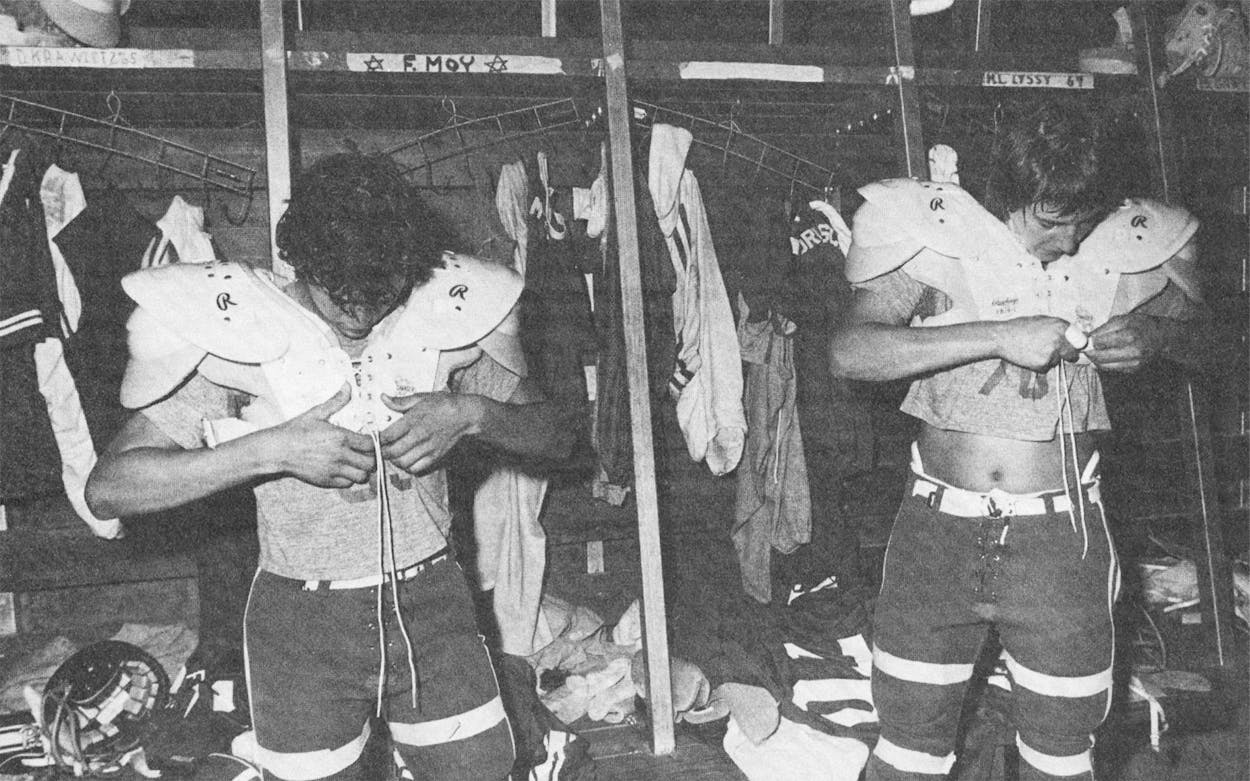

By the time they reach high school, if they’re still playing, they should have reason to be confident, having passed considerable winnowing already. They feel accomplished and even natural in their cleats and pads, in those claustrophobic helmets. The fraternal argot of football—the terms and nicknames, historical details and current standings—comes easily to them. For hours and hours they have drilled at fundamentals, honing their timing on trap-blocks and pass patterns; they are familiar with multiple offenses and shifting defenses; they have mastered the contents of two-hundred-page playbooks—larger than most small colleges employ—they know how football is supposed to be played. What doubts they have are simpler, deeper.

They are still just boys, after all, fifteen or sixteen years old, seventeen at most, still too young to really shave or legally drink, to vote or enlist or give formal consent to anything at all. They have strong and healthy Texas-bred bodies but children’s eyes—clear, wide, vulnerable eyes that reveal more than they see. There is often still a little baby fat as well, pudgy ankles and cheeks that not even summer-camp workouts could tighten up. Their youth and fecklessness are obvious. Officially classified as minors, they are the wards or dependents of virtually every adult they encounter, and they are inclined to bridle a bit. They are at that age when a boy must begin to believe in himself if he hopes to be a man, and all that supervision can be awfully discouraging.

Which is the biggest reason they come to football. On Thursday night, if they play on the varsity, they are assigned no homework. On Friday morning they wear their game jerseys to school and not only their classmates but also their teachers accord them respect, as if they were important persons. The entire school assembles to acclaim them in the gym; the band clamors martially while girls yell and leap about; the principal speaks for everyone, he says, when he tells the team they’re all behind them 100 per cent. At public pep rallies, every politician for thirty miles around will flatter them, prominent businessmen rise to salute them, ministers bless them and pray for their success. Finally their coach stands up and with prosaic but ardent sincerity he proclaims his pride and faith in them, predicting victory that night; banners wave, trumpets blare, everyone cheers. Through it all the young Football Heroes sit quietly taking it in, scarcely acknowledging the hoorah, very self-conscious, trying to convince themselves that they aren’t really children.

As always with would-be heroes, the strength of their conviction will help determine their success. They are not so ready to hit one another as they like to pretend. Most schoolboy football injuries occur during practices rather than games—the reverse of college and professional injuries—for the simple reason that they find it hard to be mean and serious at the same time. Bolder in their dreams than they know themselves to be, they are easily intimidated, so they usually hit the way children do: with their eyes closed. The most frequent admonition from a high school coach to his boys is “Open your eyes!” As if it were easy.

Friday-night football is all wish and grit, stalemate and miracle; every play requires the collaboration of adolescent minds and wills, all in a hurry and under pressure. Typically this produces vigorous confusion, misdirected plays and desperation hand-offs, horrendous pileups, frequent penalties.

From the stands it’s hard to tell brilliant improvisations from the simple accidents; everything looks ad-libbed, ill-advised, stalled by hesitations. After every play there are long pauses as the boys recover their illusions, tramping slowly back to their huddles with downcast eyes and clenched fists. The game appears a tedious series of team collisions and shrill whistles, yellow flags, official time-outs while bodies are unpiled, shoes retrieved, players located. Public-address announcements concerning all manner of local activities—American Legion dances, firemen’s benefits, choir rehearsals—fill the gaps in the very intermittent play-by-play. The crowd’s attention wanes and wanders to the cheerleaders, to the band, to one another. It is a time of community ease and togetherness, a time demanding patience. Then in an instant they can all be on their feet and shouting—even the announcer shouts—unified by an act of grace.

Somehow out of the clumsy teenage struggle come astonishments of poise, a daring run, a decisive tackle, a breathtaking pass. Inspired by possibilities, a boy rises to the moment, commits himself, lives his dream. This is football at its most ecstatic: there has never been a pro who could run with more abandon than a sixteen-year-old boy with a goal in sight. They are momentary glories, to be sure, at least for most boys, but they are all the more intense for being so fleeting, so totally unexpected. They are moments so proud and compelling that whole Texas towns will turn out to wait for them. This was one of those moments as a former player remembers it:

“I grew up in a small town in East Texas, a 2A town where we usually had a real good football team. From the time I can remember my dad was the football coach. He was baseball and basketball and track coach, too, but that was sort of on the side. He was the football coach mainly. I learned to play when I was only about six or seven years old, going with Dad to the team practices. Even for my age I was very small, but I was quick and fast, and I loved competing with guys much bigger than me. I loved the physical contact, too. There was something about football—the hitting, and being hit—that appealed to me. I also developed very good coordination when I was very young. I guess it was mostly because Dad paid me in the summers and after school to go into the gym and shoot basketball, or hit baseballs, or throw a football. He said it would be worth it in the long run—to him and to me—for him to pay me to do that, rather than me being paid by somebody else to work for them at some meaningless job.

“By the time I was ten, I could outrun a lot of guys on the varsity football team, which they didn’t like very much because if I outran them in the wind sprints, then Dad made them do laps. I was called ‘the Rabbit’ back then because I was so little and fast. By the time I was a freshman in high school I thought I was ready to be the starting varsity quarterback. But there was a senior who had played two years and he started the first two games of the season, which we won because we had a very good team that year. The third game of the year we were playing the district champions and we were behind three to nothing in the last quarter. We hadn’t been able to move the ball at all. Time was running out, and the fans—and I mean the whole town was there—were getting fed up with our team. I wanted in the game so bad I was about to go nuts, but I knew Dad wouldn’t put me in until he thought the time was right. With about two minutes left in the game, we got the ball on our own ten-yard line, just about where we’d had it all night. Dad looked around and said, ‘Where’s that damn Rabbit? Get in there. This is it. Run that option right. And don’t look back.’

“I remember that I wasn’t a bit nervous, like I thought I’d be. I took the option right and I didn’t look back. All I remember is running down that sideline as fast as I could go and hearing a voice right behind me. It was yelling, seemed like right in my ear, ‘Run, you little son of a bitch, run.’ I tried to outrun him, but he stayed with me, seemed like one step behind me, yelling ‘Run, you little son of a bitch, run.’ When I crossed the goal line for a touchdown the crowd was going crazy. Then I saw Dad, red in the face, huffing and puffing. He had chased me the last sixty yards down the sideline, right behind me, yelling in my ear.’’

Cherchez la Femme

Not until Frankie Groves came along did a girl play Texas high school football. The remote northern Panhandle farm town of Stinnett, where she lived, had a population of just nine hundred in the postwar forties, so Coach Truman Johnson—like any good football coach—was always on the lookout for promising recruits. He spotted Frankie at a school picnic: she was sixteen years old, 105 pounds, and a ruthless tackier. “I was a rough kid,” she recalls. Johnson added her to the roster in time for the 1948 homecoming game against archrival Groom. Frankie suited up at home, like the rest of her teammates, since the Stinnett field had no locker room. “She was just sensational,” said her coach, but the Groom team, no doubt bestirred by the boyish nightmare of losing to a girl, played their best game of the season to win by a touchdown. “They tried pretty hard to run over me, but they never made it,” says Frankie good-naturedly, even proudly, sounding like any old veteran recalling a tough one. “I was hit, slammed, punched, and even double-teamed. But they weren’t so tough. Heck, I didn’t even get my lipstick smeared.” Immediately after the game the state Interscholastic League ruled that girls were henceforth ineligible, ipso facto, for football. Coach Johnson was summarily fired by an indignant school board.

Thus was Texas high school football made officially pure and simple: a man’s game, reserved for boys. Any feminine involvement would be strictly supportive, in accordance with Texas tradition. It was a decision made, of course, by Texas men.

Texas girls wishing to participate have their work cut out for them. They are expected to lead cheers and twirl batons, to make music, to provide entertainment and coy motivation, to stand by their boys in their hour of need, uncritically, enthusiastically. It is a role straight out of masculine fantasy—like the role of Football Hero—and many Texas girls take to it with the same naive eagerness as the boys do their role. Beginning in the sixth or seventh grade, even earlier in some cases, they start painting banners with the junior pep squad, practicing baton or learning jumps, commencing a diligent apprenticeship that may carry them, four or five years later, to a kind of self-fulfillment.

The role gives shape and direction to their pliant teenage lives, a first sense of their own distinction. It has relatively little to do with the actual game, really, more to do with boys. High school romance is all role-playing and melodrama anyway, and football is merely the setting that creates the roles. Many a first date is to a Friday-night football game. Boys get the car for the first time and girls receive their first corsages—huge gaudy mums with foot-long ribbons, their date’s name spelled out in glitter, heavy enough to stoop their shoulders. It is the girls, too, who wear the letter jackets most proudly and conspicuously, indoors, all day, everywhere; most boys don’t wear them much until after graduation, when they’re trying to recapture that sharp sense of adolescent glory or laugh about it. But by then it’s an empty symbol and the girls are unimpressed.

Even after they grow up, though, there is still some girlish part of many Texas women that responds to the would-be heroes of schoolboy football. The crowds at Texas high school games invariably include as many women as men—hardly the case at college or professional games—and the women are always the most uncritical, the most enthusiastic. The men, spoiled by Monday Night Football and instant replays, often find the Friday-night version clumsy and slow; they may grumble and pout, harass the coach and the referees, sometimes yelling epithets at their own team, their own boys. Only the women are completely loyal and supportive, as if they, too, were trying to recapture something old and fondly remembered, when they still had men they could truly believe in.

Winning and Losing

High school football is an obvious rite of passage for the boys who play it. Flexing their muscles for the first time in public, instead of merely around each other, they bear down manfully, trying to open their eyes and look convincingly cool and determined, sure of themselves: like Football Heroes. The role has the same bold features and dimensions as Texas’ traditional image of manhood, and tradition-minded Texans are quick to respond to it. More than the actual game itself they come to applaud the values that football expresses—Texas values of land and will, of mutual effort—encouraging their boys to embrace and adhere to them. Most of the young Football Heroes will never play organized football again after high school, and by the time they are seniors they usually realize it. Some never manage to accept it, of course, thus crippling themselves, but most find other pursuits that suit them better or seem more rewarding, more likely of fulfillment.

Fulfillment is often confused with winning by many Texans, who tend like Darwin to regard living as a competition, and this, too, is neatly exemplified by football. This is especially so at the high school level, where the boyish Football Hero sees himself, first and foremost, as a team member. He wins for his school, his girlfriend, his mother and father, brothers and sisters, for his town or neighborhood, for his coach and his teammates. These are truly unselfish victories, celebrated accordingly. On the winning side of a Friday-night football field there is more boyish hugging, touching, and unrestrained affection than most Texas males will permit themselves for the rest of their lives.

On the losing side the desolation can seem overwhelming: the boys are all grief-stricken, with tears and averted eyes, children again. Even the most sensitive coaches admit there is no consoling a team that drops the big game—unless maybe their girlfriends can do it, and the coaches are divided on whether even that is possible. Nonetheless, all coaches firmly believe that their boys will be back at practice come Monday afternoon; resilience is one of the major virtues of the Football Hero, after all, perhaps the most important one. As they cross the field to shake each other’s hand, formally sealing the end of the game, the two opposing coaches represent their teams and towns in accepting its conclusions—final conclusions until next week, or next season, or the next, when new heroes, just like the old, play to another, separate conclusion that isn’t final after all.

- More About:

- Sports

- TM Classics

- High School Football