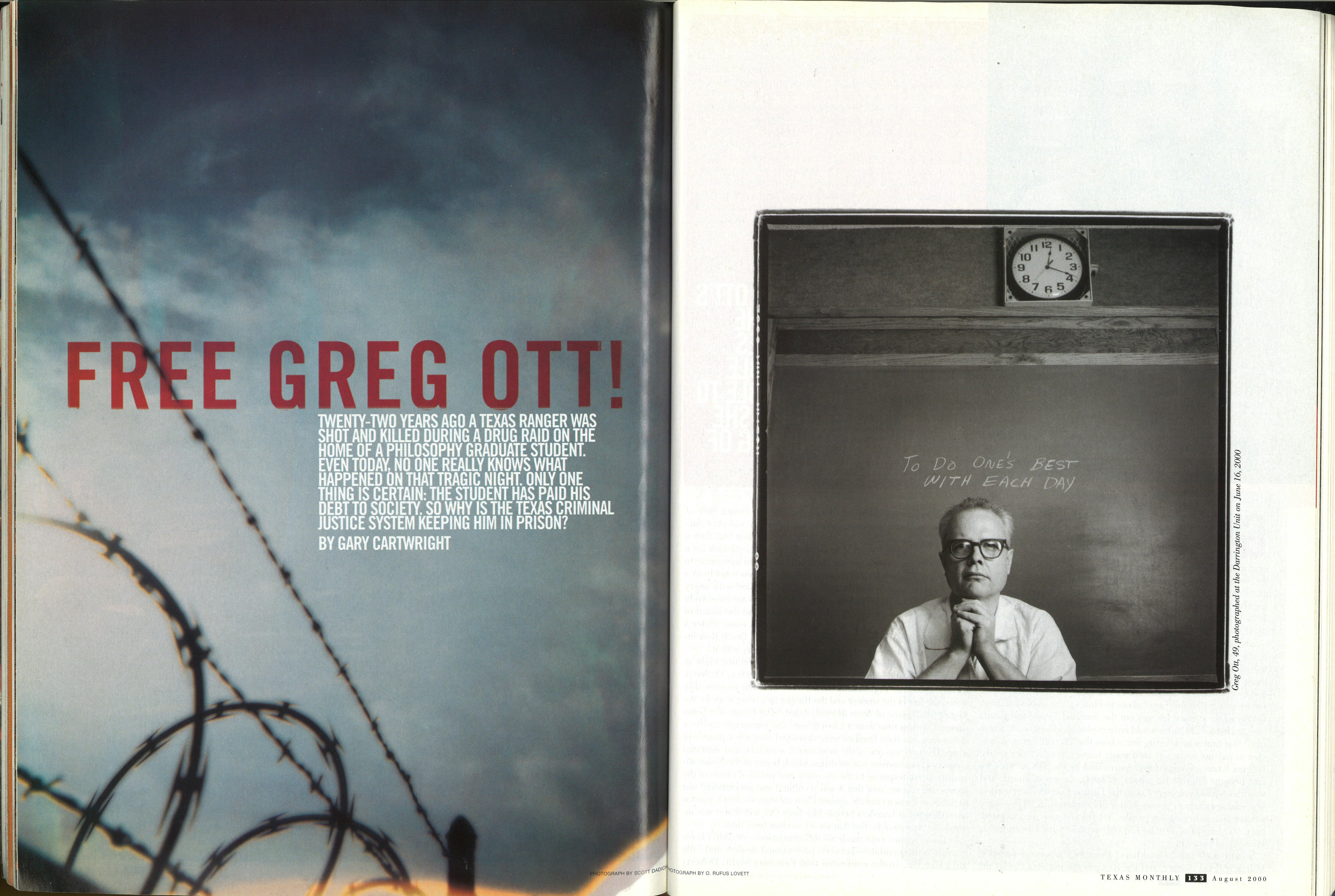

Gregory Ott, Texas Department of Criminal Justice #282372, is the pluperfect inmate, the poster boy for the way a parole system ought to work. For more than two decades the TDCJ has repeatedly taken note of his cooperation, work ethic, initiative, upbeat attitude, and selflessness. As one corrections officer noted in a letter to the Board of Pardons and Paroles, Ott “is almost an alien in this environment, portraying characteristics that would qualify him as a model citizen.” In 1982 Ott risked his life to save a guard who was being attacked by another inmate. “He put his life on the line for that officer,” recalled David Christian, who was the warden of the Darrington Unit at the time. In 1994 he probably saved an entire wing of inmates and guards at Darrington. Ott was the boiler room attendant one night when three prisoners who were staging a breakout beat him and bound him with tape, then killed the power to the boiler despite Ott’s warning that they were about to blow up the whole building. Ott somehow wormed his way out the door and alerted the guards minutes before the boiler would have exploded. His only infraction in all that time was ordering forms from the Internal Revenue Service to pay tax on money he’d made handcrafting leather goods: IRS tax forms are considered contraband by the TDCJ. Since he first became eligible for parole, in 1990, dozens of guards and wardens—and even Jerry Cobb, the Denton County district attorney who sent him to prison with a life sentence in 1978—have written letters urging his parole. Yet Ott remains incarcerated; only .02 percent of TDCJ’s 153,000 prisoners have been inside longer than Greg Ott.

So why is he still behind bars? Because Ott was convicted of killing a Texas Ranger, and the Rangers are not about to let the parole board forget it—even though this was far from a case of cold-blooded murder. Ranger Bobby Paul Doherty was shot during a poorly planned, sloppily executed drug raid that Ott, then a 27-year-old graduate student at North Texas State, mistook for a robbery attempt. Twice the parole board has been agreeable to Ott’s release, but each time he got the necessary two votes from a three-member panel, the Rangers flooded the board with angry protests and somebody backed down. The Rangers are effectively exercising veto power over Greg Ott’s freedom, and the Board of Pardons and Paroles—the same agency that has come under a national spotlight this year as the last resort before Death Row inmates are executed—is letting the Rangers get away with it.

For 22 years I have thought about what happened that night in February 1978 at the farmhouse outside of Denton where Ott lived. I wrote about the improbable series of events that inextricably linked the fate of the student and the Ranger in a cover story for the August 1978 issue of Texas Monthly titled “The Death of a Texas Ranger.” In less time than it takes to read this paragraph, the lives of two men and their families were destroyed over a few pounds of weed. The raid was one of the most tragic, senseless, and shameful episodes in our endless war on drugs, which began as the Nixon administration’s response to the excesses and political chaos of the sixties. We can see now that it was a cultural and generational war as much as it was a crusade against illicit substances, that it was too often directed at harmless people like Greg Ott, and that it was intrinsically unwinnable. But that wasn’t so clear back then.

In the seventies cops made no differentiation—or didn’t know enough to differentiate—between professional dealers and little guys like Ott. In the confusion that February night, Doherty never saw the man who shot him: The bullet passed through a closed door maybe two seconds after an undercover agent inside the house fired at Ott. Nor did Ott see Bob Doherty. I don’t think Ott even knew this was a drug raid, or that his house was surrounded by police officers. He did know that he had been robbed on two previous occasions; in one a woman friend was beaten with a shotgun. I am certain that Ott didn’t knowingly, willfully shoot a police officer, and so was the jury at his trial, otherwise the sentence would have been death and this story would have been buried years ago.

Still haunted by the memory, still trying to sort through the events and assess the blame, I returned this spring to the scene and talked again to the people involved. A lot of mistakes were made, I know now, some of them by me. I had assumed all these years, just as the cops had assumed that night, that Ott was a major drug dealer. My recent investigation convinces me otherwise. Ott smoked a lot of marijuana and sold lids to friends—usually at cost—but he wasn’t a dealer except in the narrowest sense. This whole tragic affair began with a big lie, and the lies and distortions have escalated through the years. Some of them were inadvertent, people careless with what they reported or bending to preconceptions, but together they have greatly enhanced the campaign to ensure that Ott remains behind bars. The campaign has likewise benefited from a change in our attitudes about crime. Once we used to talk about rehabilitating criminals, but our failed drug policy and failed parole policy have hardened us. Now we think mainly of retribution.

We’ll never know exactly what happened the night Ranger Doherty was killed, but one thing is clear: Greg Ott wasn’t a threat to society until the cops invaded his home, and he hasn’t been a threat since. It’s time to parole him.

Ott lived alone in 1978. he had graduated summa cum laude in psychology from North Texas State and worked five nights a week on his master’s thesis in philosophy, an effort to compare Heidegger’s phenomenology with Zen haiku poetry. “I seek to understand Absurdity’s role in contemporary human affairs,” he wrote, never dreaming that he would experience it firsthand. He was a dedicated ascetic who drove an old Fiat, bought his clothes from the Salvation Army, and bragged about grooving on poverty. Nevertheless, he had a strong work ethic, which he learned from his father, Bruce Ott, a retired Army colonel, and his brother, Bruce Dennis Ott, an American Airlines pilot. Greg Ott had added at his own expense two rooms and a new entranceway to his rent house at Twin Pines Ranch, north of Denton, and he supported himself by making and selling leather goods and raising calves. He was as eccentric as he was brilliant, a familiar figure on campus with his flowing beard and long hair, his leather cap, and a gaudy assortment of rings. “He looked like a big leather Christmas tree,” recalled Elise Jean Knox, who attended NTSU at the time. You’d see him with an armload of books in the student center or in the coffeehouses arguing existentialism. Ott smoked pot all day long, every day—in his view, it made the world “normal”—but he had never been in serious trouble. As a teenager he had spent fifteen months in psychiatric detention at the Timberlawn clinic in Dallas, where he was treated for an adolescent personality disorder. The treatment was the military’s way of dealing with a teenage scuffle at Fort Sam Houston, where Greg had slashed a high school bully with his Boy Scout knife. Since his father’s career was on the line, the family agreed to the detention. But Ott had never used drugs before he went to Timberlawn. Nor did he have a police record.

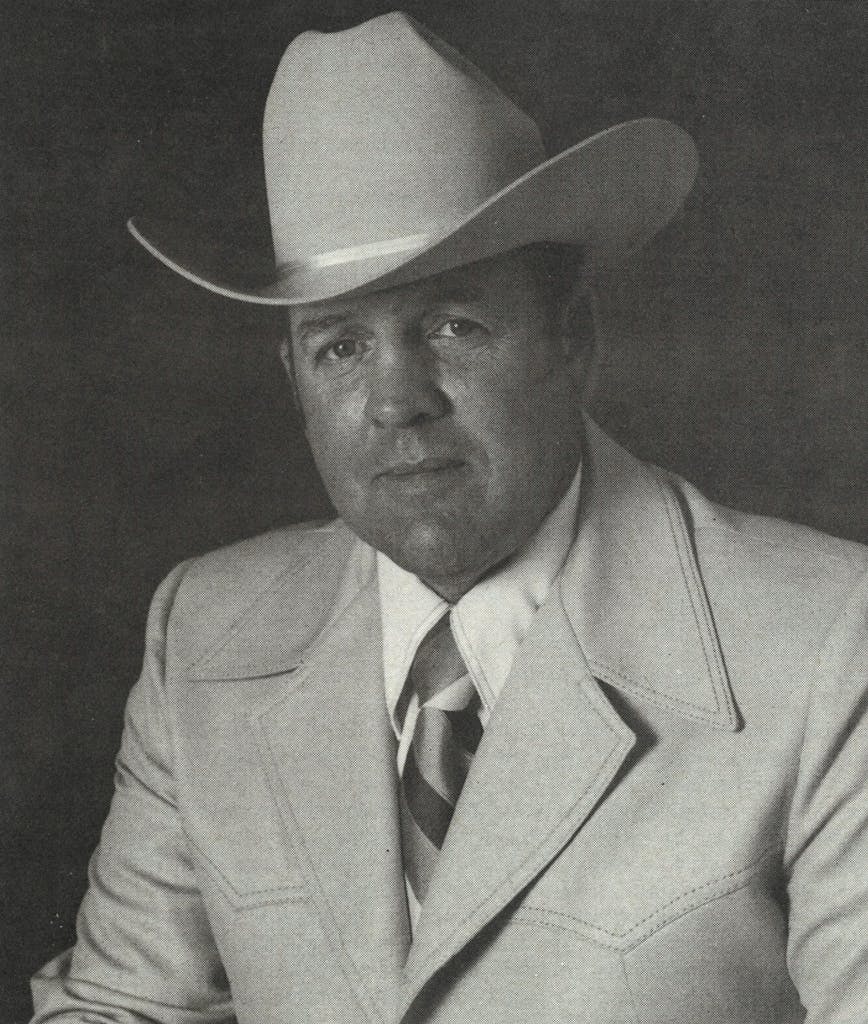

Narcotics officers with the Department of Public Safety had never heard his name until a few hours before the raid, when they busted a dealer named James Leonard Baker. Baker’s bust had been weeks in the planning. Captain Dwight Crawford, an investigator for the Denton County Sheriff’s Department, had been told by a thug who had robbed a hospital pharmacy that Baker and a “local attorney” who was never otherwise identified were part of a major drug ring. Sensing that this was something big, Crawford called his friend Bob Doherty, who in turn notified Weldon Lucas, then the regional supervisor of the DPS narcotics service. In the parlance of law enforcement, Baker’s arrest was a “buy-bust” operation. Buy money was hard to come by in the 1970’s: Buy-bust operations were high-risk because of the unknowns involved but were deemed acceptable because lawmen could recover the money on the spot.

Posing as a gangster from St. Louis, DPS undercover agent Ben Neel arranged to buy fifty pounds of pot from Baker, at which time Doherty, Crawford, and two deputies rushed into the room and busted the dealer and two of his friends. The operation went perfectly, except for one thing: Baker was thirty pounds light. The difference between fifty and twenty pounds was of no legal consequence—the lawmen should have taken Baker to jail and called it a night—but by now they were caught up in the chase more than the crime. Baker was promised certain unspecified considerations if he would name names and help them get the remaining pounds. Baker claimed that he could get a large amount from Greg Ott. He told them that Ott was a “heavy dealer,” which was a lie. Baker barely knew Ott. They had met through a mutual friend, and Baker had smoked dope on several occasions at Ott’s house, which was coincidentally adjacent to a ranch owned by a man named Rex Cauble.

That name meant something to Bob Doherty. In the 1970’s Denton was a major drug center. One of the cases Bob Doherty was working at the time of his death involved the clandestine movements of Cauble, a wealthy rancher and prominent antidrug crusader who paid for and personally recorded antidrug messages on a local radio station. Cauble was a friend, a confidant, and sometimes an employer of a number of DPS narcotics agents or former agents. The Texas Rangers’ distrust of DPS narcotics officers was well known in law enforcement circles even though the Rangers are a branch of the DPS. Cauble went out of his way to kiss up to the narcs, hosting barbecues for them, furnishing them with buy money for undercover operations, making his airplanes available. Doherty suspected that Cauble’s real business was smuggling dope. And he turned out to be right. In 1982, four years after Doherty was killed, Cauble was convicted of being the brains and money behind the so-called Cowboy Mafia, a smuggling ring that imported more than one hundred tons of marijuana [see “Rex Cauble and the Cowboy Mafia,” Texas Monthly, November 1980]. Perhaps Doherty thought that Ott and his neighbor Cauble were somehow connected.

Flying now by the seat of their pants, the lawmen instructed Baker to telephone Ott and say that he was desperate to find some dope for an important client from St. Louis. Ott allowed that he had a couple of lids to spare. “No, man,” Baker pleaded, “I’ve got to have a lot. Isn’t there anything you can do?” Ott promised to make some phone calls, foolishly placing himself in the middle of a major dope deal. Another North Texas State student, identified only as “Larry,” delivered twenty pounds of marijuana to the barn behind Ott’s house later that night, at which time the raiding party went into action.

The raid was an accident waiting to happen. It was now after ten o’clock and none of the lawmen were in uniform. Some had been drinking beer earlier in the evening, and undercover agent Ben Neel had been seen smoking pot, or at least pretending to, in his undercover role. While Neel and the informant Baker went inside Ott’s house to make the buy, the five members of the raiding party, which now included a young DPS narcotics agent named Don Jones, hid under a blanket in the back of a camper. Neel followed Ott to the barn to get the marijuana, and when they returned to the house, he left the back door open, a signal that the buy was complete.

Only God knows for certain what happened in the next few seconds. Neel testified that Ott went back to close the door, and he observed Ott wearing a holster and gun. Neel drew his .45 and shouted, “Police officer! Freeze!” Ott acknowledged to me that he had been wearing a holster—one that he had just made and was molding to his belt before delivering it to a customer—but claimed the holster was empty. He said he didn’t hear Neel identify himself as an officer or realize that other police officers were outside. Fearing that he was being robbed again, Ott bolted for the walk-through closet where he kept a .38, along with a .22 rifle and a twelve-gauge shotgun. Neel fired and missed. As Ott grabbed his .38 from the shelf, Ott maintains, the gun became entangled in a beaded curtain and went off accidentally.

No one actually saw Ott fire a shot—and, for that matter, no one can prove that the shot he fired was the fatal one. The bullet that killed Doherty passed through the closed door of the new entranceway, which the Ranger was apparently about to kick down when Ott’s gun discharged. The bullet was so badly fragmented that it was impossible to say that it came from Ott’s gun. Witnesses told conflicting stories. In his original statement, the informant Baker confirmed Neel’s version, but in a deposition taken later by Ott’s attorney, Baker changed his story, claiming that Neel fired not one but two shots. Captain Crawford claimed that he shouted, “Police officers!” twice before a shot was fired, but Neel didn’t hear him, so it’s safe to speculate that Ott didn’t either. The postmortem investigation was as inept as the raid. One investigator rammed a pencil through the bullet hole in the door, making it impossible to tell whether the hole was caused by a .45 or a .38 slug. Neel didn’t surrender his .45 until at least an hour after the shooting of Doherty; if he had indeed fired more than one round, as Baker claimed, he would have had ample time to reload.

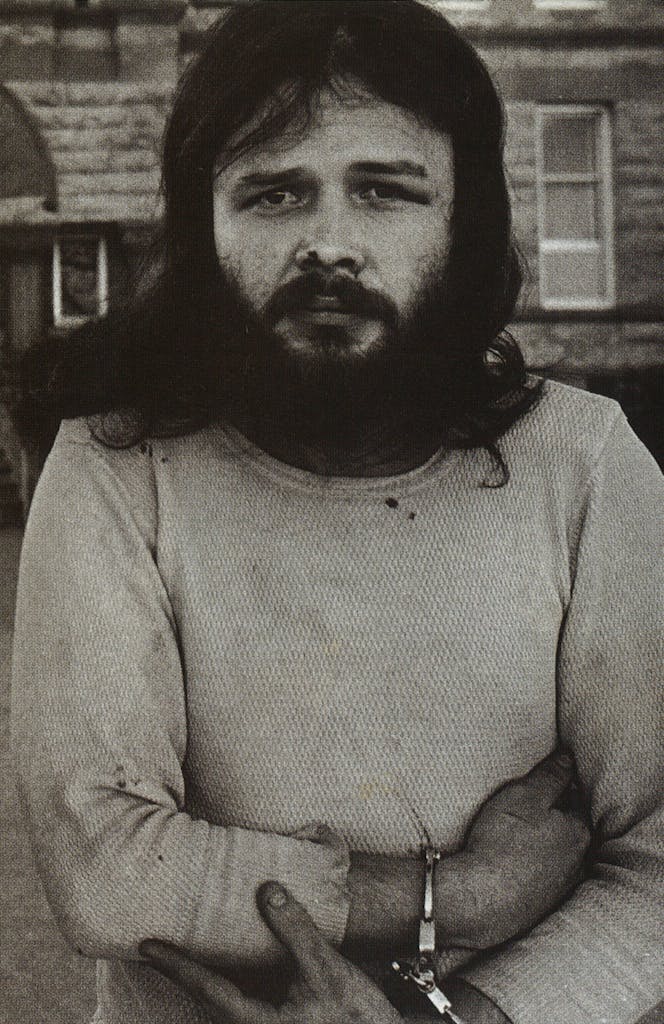

Doherty was the first Texas Ranger killed in the line of duty in 47 years, and the story attracted national attention. It was aired early the following morning on ABC’s Good Morning America, and for days afterward newspapers and television stations featured the photograph of the killer. Carolyn Doherty, Bob’s widow, told me at the time about her reaction to it. She and Bob had been high school sweethearts when they married 21 years earlier, and they had two teenagers, Buster and Kelly. Though Carolyn had joked to friends that she and Bob were “Mr. and Mrs. Redneck,” I found her to be a gentle and thoughtful woman, and I fought back tears listening to her describe that frantic ride to the emergency room, where the Ranger was dead on arrival. Then she told me about seeing Ott’s picture in the paper the next morning. The defendant’s hands were cuffed across his chest and his eyes burned with a terrible light through his wild nest of long, black hair and scraggly beard. It was impossible to look at that picture, she said, without thinking, “Charles Manson.”

The defendant’s hands were cuffed across his chest and his eyes burned with a terrible light through his wild nest of long, black hair and scraggly beard. It was impossible to look at that picture, she said, without thinking, “Charles Manson.”

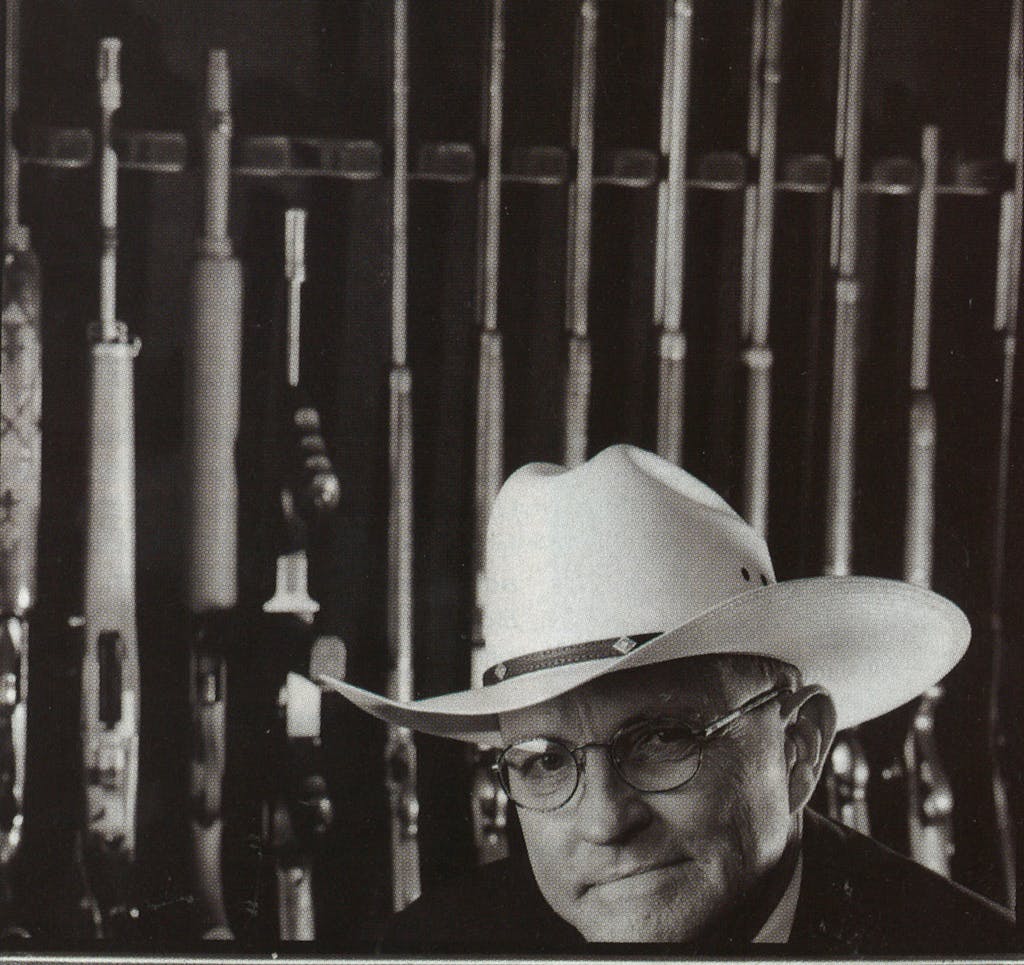

The board of pardons and paroles was ready to release Ott ten years ago. In 1990 he was transferred to the Walls Unit at Huntsville to process out. He was a few hours from walking free when a prison official who had never met Ott tipped off the Rangers, who immediately launched a blizzard of faxes protesting the parole, at which time the board changed its mind. Since then they have kept up the pressure. The Rangers as an organization are not opposed to Ott’s parole, or at least that’s the claim of the Ranger commander, Captain Bruce Casteel. Casteel acknowledges that he protested directly to the chairman of the parole board last year, but that was merely his personal policy. “I don’t speak for the Rangers individually,” he told me. “I wouldn’t ask them to file a protest if they didn’t feel it was the right thing to do.” Many Rangers too young to remember Doherty or the events that led to his death have nevertheless protested. “They know that a Ranger was killed and that’s inexcusable,” Casteel said.If and when Ott does get paroled, it is understood that he must be paroled out of the state, probably to Florida, where his sister and aging parents live. One member of the parole board told me that the Rangers were contacting law enforcement officials in other states and advising them against accepting Ott. “They’re cutting off any possibility he can ever be set free,” the board member said. Casteel denies knowledge of an orchestrated attempt to shut off Ott’s parole avenues but concedes: “Many retired Rangers could be making contacts—it would not surprise me.”

Orchestrated or not, the campaign to keep Ott behind bars is powerful and effective and has gone mostly unchallenged by the media. When Ott’s case comes up for its annual parole review, newspapers often republish the photo that reminds people of Manson. Sometimes they run companion pictures of Carolyn Doherty holding a photograph of her dead husband and flanked by her family. In March 1995 the Denton Record-Chronicle published a front-page story reporting that the law enforcement community was distributing petitions (they had already gathered 870 signatures) and urging people to write letters protesting Ott’s possible release. Inserted at the top of the story was a box giving the address of the Board of Pardons and Paroles. People who had never heard of Ott and knew nothing of the circumstances of his crime were writing letters or lining up in supermarket parking lots to sign the petition. The Record-Chronicle story was full of misinformation, some of it, I’m ashamed to admit, taken from my piece in Texas Monthly. At the time of the trial, I had read a copy of Ott’s psychiatric record, compiled while he was at Timberlawn. Using the report as my source, I reported that Ott had once attempted to stab his mother and his brother and that he had been a h

eroin addict. None of this is true, I’ve learned since from his family.

The lawmen who took part in the raid have gradually obscured the record in a way that makes Ott look like a cold-blooded killer. A story in the Record-Chronicle last year and a similar one in 1995 included several astonishing recollections that are not in the record or the trial transcript. Dwight Crawford of the Denton County Sheriff’s Department, whose phone call to Doherty about James Leonard Baker started the tragic affair, was quoted as recalling: “Ott opened the door, saw [Ranger Doherty] and slammed it shut in his face, firing at the same time.” If Crawford had so testified at the trial, Ott would have been executed long ago. I asked Crawford about the quote when I visited Denton this spring. “I don’t remember saying that,” he told me, shaking his head. “I think maybe I read something along those lines in one of the reports.” Crawford, who is now a forensic investigator for the county medical examiner, had kept his case file and allowed me to read it. There’s nothing remotely like that recollection in any of the documents. Other lawmen have taken similar liberties. When Ott’s case was up for review last year, Denton County sheriff Weldon Lucas, the former DPS supervisor of narcotics for the area and a former Ranger, told the Dallas Morning News: “Twenty-one years ago [Ott] was willing to shoot a police officer to protect his drug investment. [My opposition to the parole] is not blind loyalty to the Rangers. I am thinking of the danger he would bring to the police officers out there today. I don’t think he’s changed.”

The supposition that Ott killed to protect his stash became a handy rationale after Doherty was killed and has remained a rationale for keeping him in prison. It neatly explains why the raiding party went after a hippie weed-head as though it had cornered the French Connection. One of the most interesting things I read in Crawford’s file was a previously undisclosed second statement from Baker, taken seven hours after his initial statement. In this revised remembrance, the informant told of buying twenty or thirty pounds of marijuana from Ott over the previous year and spoke of Ott’s extreme paranoia and his vow to “kill anybody that tries to steal my stuff.” This statement was so at odds with what I knew about Ott from his family and friends that I checked with them again, reading them Baker’s comments. “That’s ridiculous. Greg wasn’t a dealer by any stretch of the imagination,” said James Althaus, a college friend who has visited Ott regularly in prison. “He was philosophically nonviolent. He was very intelligent, and with that went a lot of arrogance, but he never talked about killing anybody.” Ott did have the three guns, but he kept the shotgun loaded with rock salt to protect his calves from coyotes, and the .22 was for target practice and hunting rabbits. He purchased the .38 after the second robbery.

Understandably, the subject of Ott’s parole arouses considerable emotion among law enforcement people in Denton. DPS narcotics agent Don Jones, who was on the raid, told me angrily, “The jury gave Ott life. I don’t think that a writer or a parole board ought to arbitrarily decide he should get out. If that’s the case we should do away with the writer and the parole board.” Jones expressed no regrets over the tactics used that night, and neither did any of the others. “It should have been a simple deal,” Ben Neel told me. “I meet Ott, I make the buy, we make the bust. I didn’t know he had a gun.” Neel described Ott as a “cold-blooded murderer” and said, “There’s no place in society for a man who shoots a police officer.”

A few years after the Ranger was killed, Neel got caught up in the Rex Cauble investigation. He was subpoenaed by Cauble’s attorney and testified that Cauble was a good friend of the DPS narcotics service and violently opposed to any type of drugs. When he denied that he knew that Cauble was the target of an investigation before it became public, federal prosecutors indicted him for perjury. Weldon Lucas and other lawmen testified against him. Though Neel was acquitted, the cozy arrangement between Cauble and DPS narcotics continues to arouse bitter feelings. Dwight Crawford believes that the Rangers ended the Ott investigation too soon. If they’d kept digging, he speculates, they may have connected what happened that night at Ott’s house to Cauble and his association with narcotics agents.

One of the most passionate crusaders against Ott’s parole is Denton County’s current district attorney, Bruce Isaacks, who first learned of the case by reading my account in Texas Monthly in 1978. Isaacks was a student at the University of Texas at Arlington at the time and remembers being surprised “that anyone would have the gall to murder a Texas Ranger.” His ambition was to be a highway patrolman—he’d been a reserve policeman in his hometown of Joshua—but later he decided to become a prosecutor. In 1990, when district attorney Jerry Cobb declined to protest Ott’s parole, Isaacks used it as a campaign issue and defeated him. Isaacks has filed an annual protest and solicited protests from other law enforcement officials and politicians. Last year he wrote a letter to fellow Republican George W. Bush, warning the governor that Ott “is a violent and dangerous criminal.” He urged Bush to “take the time right now” to write a protest letter and to encourage his friends to do the same.

I asked Isaacks what he knew about Ott’s case. Had he read the trial transcript or the case file? “I looked at the file,” he replied, “And I talked about it with Weldon Lucas, Dwight Crawford, and Don Jones.” Ott’s fate is open and shut, in the opinion of this DA: “Anyone who kills a police officer shouldn’t be let out until they carry him out in a pine box.”

When Ott comes up for parole in late August or early September, his fate will be in the hands of the same three-member panel that considered his case last year. Linda Garcia, a former Harris County prosecutor, and Cynthia Tauss of League City, who has long been involved in juvenile justice issues, both gave him favorable votes last year, but when the protests poured in, Tauss withdrew her vote. The third member of the panel, Houston attorney Dan Lang, gave Ott thumbs down. State law prohibits board members from discussing protests or any information in the file. “All I can tell you is that additional information was received,” Tauss said. Since Garcia presumably received the same “additional information,” I asked her, why didn’t she change her vote? “Reasonable minds can differ,” Garcia replied. Because parole is a privilege, not a right, inmates have no due process protection. Not even the inmate’s lawyer can see his file. It is impossible, therefore, to defend against any “additional information” a protester may proffer, however inaccurate or malicious. What Tauss, Garcia, and Lang received was not additional information, of course, but opinion—an atavistic reaction aggravated by more than a century and a half of Texas Ranger myth. A Ranger was killed in the line of duty, and it’s the Rangers’ opinion that Ott should be deprived of the rest of his life too, even if that means to die in prison.

Attorney Bill Habern of Riverside, who specializes in parole matters and has represented Ott before the board, told me of incidents in which pages of criminal histories ended up in the wrong inmates’ files. “The process has become highly politicized,” Habern said. “I don’t mean that the governor influences the outcome of parole votes, but so long as board members serve at his will, they are limited in voting their conscience.” All eighteen members of the current board are Bush appointees. The parole rate has dropped steadily, from a high of 79 percent during the prison-overcrowding crisis of 1990. By the end of Ann Richards’ term, it was down to 28 percent; under Bush it has hovered around 20 percent. Legislative changes have contributed to the drop in parole rates: For example, inmates who commit violent crimes must serve 50 percent of their sentences instead of the previous 25 percent.

Board members have little time for deliberations: A prisoner’s file can contain hundreds of pages. Last year more than 100,000 cases came up for vote, which computes to about seven or eight minutes of attention to each file per board member based on a forty-hour week. In most cases inmates don’t get an opportunity to appear before the board. Jack Kyle, the chairman of the board under Ann Richards, believes that the flaws in the process could be largely corrected if the Legislature would do away with the secrecy requirements. “They are unfair,” Kyle told me, “not only to the inmates, but to the board as well. People who know nothing about a case can protest by signing a petition in a Wal-Mart parking lot.”

Some of Ott’s supporters hope that the vote will be delayed until after the election. Tauss and Garcia both assured me that politics will play no role in how they vote. I believe them. They have clearly agonized over this case. “My reputation is at stake,” Tauss told me, confessing that she has had nightmares over her previous Ott vote. Garcia told me, “It’s hard to take the position that he hasn’t earned parole, but the million-dollar question is, Has someone been punished enough?” The board is not an appellate court; it doesn’t decide guilt or innocence or whether a trial was fair. It does look at such factors as whether an inmate has been punished enough or is a continued threat to society.

Carolyn Doherty still lives in the same white brick home in Azle where we met 22 years ago. Her daughter, Kelly, is married now and lives next door with her own pair of teenagers. Buster lives in another part of town and works at the local hospital. He wanted to go into law enforcement but worried how his mother would react and found a safer occupation. Buster’s wife delivered twin boys last year, named after a grandfather they will never know—Bobby Tavish Doherty and Brodie Paul Doherty. “Doherty is an Irish name,” Carolyn reminds me. “‘Tavish’ is the Gaelic word for twin, and ‘Brodie’ means brother.” Though another protest crusade is imminent, she dreads it. “Every time this comes up, they want me to write a letter,” she says, her voice strained from an ordeal that cannot be avoided. “It happens every year, and every time, it opens old wounds. I’ve always gone along because I owe it to Bob. But now I have two one-year-old grandsons in the house and they are a handful.” Carolyn tells me, as she has told others, that she knows that Ott will eventually be paroled. When that happens, she will be relieved, not because he is free but because she will know that she did everything she could to honor her husband’s memory.Ott’s family lives with its own tortured memories, praying that Greg will be released while his parents are still alive. “What hurts is how they portray him as less than human,” says Bruce Dennis Ott, who still flies for American Airlines. We are seated at his dining room table, at his home in Plano, sifting through letters and newspaper clippings. He points to a newspaper photograph of the Doherty family and tells me, “People don’t accept that Greg also has a loving family that suffers every day for what happened. I understand their grief, but if the lawmen had done their job right the first time, none of this would have happened.”

Bruce is two years older than Greg and, in some ways, his brother’s spiritual opposite. Greg was the nonconformist, always seeking new answers to old questions, but Bruce knew exactly what he wanted—he wanted to fly. Bruce, his wife Cynde, and their sons, Dennis and Chris, speak of Greg not as someone who has been away but as a living presence in their home. “He never misses my birthday,” says Chris, who wasn’t born when his uncle went to prison.

I leaf through dozens of letters detailing the shattered dreams of the Otts. Greg’s favorite phrase is the French expression “c’est la vie”—an ironic reflection on life from a lifer. James Althaus, the old college friend who used to argue existentialism with Greg, tells me: “I’ve come to realize that his belief in existentialism is what got him through all these years.” The most agonizing letter is one from March 1990, written a few days after Greg’s parole was first approved and then rescinded mere hours before he expected to go free. “Drained by a demise of a thousand lacerations I struggle to find words,” he tells his family. “A new birth . . . a new death . . . a new emptiness—yet each day must be met with a best effort, if only because it is all that remains.” In a letter to Helen Copitka, a former member of the parole board who took up his cause years ago, he wrote of the terminal illness of one of his few inmate friends, Steve Broom: “You see, I don’t enjoy my peers, especially those of my race that fill these halls. Never have. Always, for nearly twenty years, I’ve done these days alone. Along comes Broom and he is likable and he becomes my friend and now I watch him dying—dying with an inner strength that I’m not sure I would be able to muster. I guess this is how we grow old.”

On September 14 Greg Ott will turn fifty, an age when most people begin to think of retirement. He thinks only of freedom. Looking at him through the mesh cage of the visitors’ room at Darrington, I am struck by how he has changed since I last saw him, in 1978. He’s heavier, and his hairline is receding, but there is something else, something cerebral and yet chilling—an attitude numbed down. I sense the deep-seated submission that you see in people whose future is their past. The arrogance of youth has slipped away without disturbing the philosophical imperative that sent him in search of the nature of absurdity. “After all these years I accept my share of the blame for what happened,” Ott tells me, his voice so soft I have to strain to hear. “I wasn’t actively engaged in marketing illegal substances. I was going to college. I smoked marijuana, and I freely chose the road that led me here, but I didn’t knowingly, willfully shoot anybody.”

Ott didn’t testify at his trial, but before sentencing, he was allowed to address the court. He said, “You can put me in a tiny cage, but you can’t take the goodness of my being away from me. You cannot make me bitter or hateful. You have done what you needed to do; I will remain good and in so doing, honor the orders of the courts.” That’s exactly what he has done. Mistakes were made years ago, both by Ott and by the lawmen. It is time for everyone to concede that. This time, I truly pray, that the parole board will do the right thing and set Greg Ott free.