This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

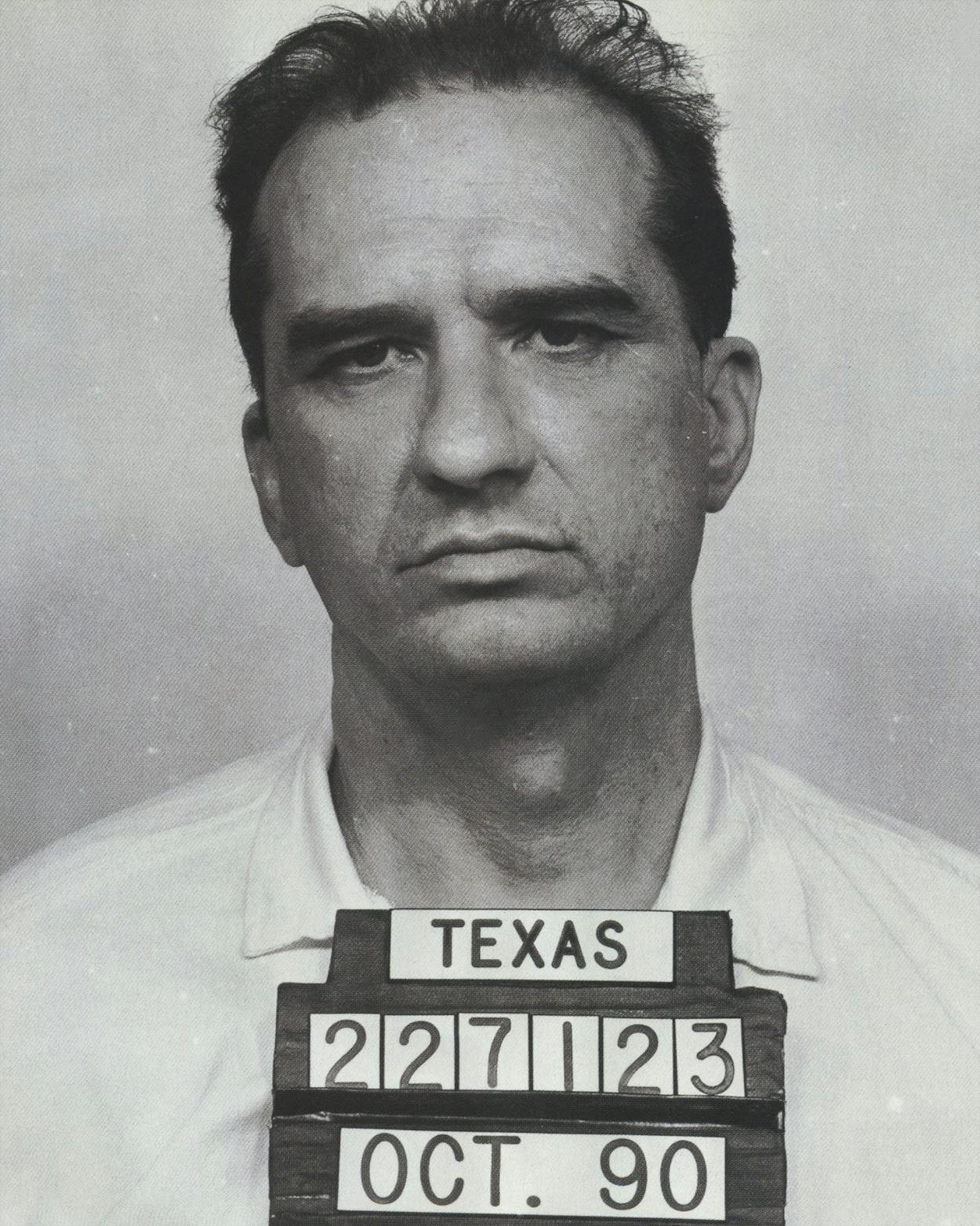

Twenty-one years after he should have died in the electric chair for the savage murder of three teenagers, Kenneth McDuff was back on the streets, as cocky and mean and dangerous as ever. In the small Central Texas community of Rosebud, where McDuff grew up, people pumped shells into shotguns and shoved heavy pieces of furniture in front of double- and triple-locked doors. “This is a walking town,” said John Killgore, the editor of the Rosebud News, “but these days you see very few people on the streets. McDuff’s return has scared the hell out of this town.” At Festival Days in the Falls County seat of Marlin, word spread like wildfire that McDuff had sworn to show up and kill one person for every day he spent in prison. Tommy Sammon, who had humiliated McDuff in a playground fight in the eighth grade, worried about his teenage children. A man who had once prevented McDuff from crushing the throat of a young woman with a broomstick—a dress rehearsal for what McDuff would do to a teenage girl in southern Tarrant County some months later—pushed the button on his telephone answering machine and was greeted with the sound of three gunshots. No question about it: Kenneth McDuff was back in town.

It was October 11, 1989. Falls County sheriff Larry Pamplin telephoned his longtime friend deputy U.S. marshal Parnell McNamara in Waco and told him, “You’re not going to believe what happened, Parnell. They’ve paroled Kenneth McDuff.” There was a brittle silence as McNamara processed this totally illogical piece of information, then McNamara laconically inquired, “Have they gone crazy?” There didn’t seem to be any other explanation. McDuff wasn’t just another killer who had fallen through a crack in the system; he was the most violent, sadistic, remorseless criminal either of these veteran lawmen had ever come across. Their association with McDuff went back more than a quarter of a century, because their fathers, the late deputy U.S. marshal T. P. McNamara and the late Falls County sheriff Brady Pamplin, had seen McDuff’s savagery up close. Brady Pamplin was the lawman who had arrested McDuff in 1966 for the three murders—literally shooting McDuff’s car to pieces as he tried to escape. People had always wondered why Brady Pamplin didn’t kill McDuff when he had the chance; no telling how many lives that would have saved. Larry Pamplin and Parnell McNamara and his brother, Mike—who is also a deputy marshal in Waco—were teenagers at the time, about the same age as McDuff, and the incident had made a permanent impression on them. Parnell McNamara remembered how Brady Pamplin’s voice broke as he described the killings to Parnell’s father: “T.P., he put a broomstick across the throat of that poor little girl up in Tarrant County and broke her neck just like you’d kill a possum.” Brady Pamplin was as tough and as able as any lawman who ever lived, a legendary figure who had been a Texas Ranger before World War II and had served as sheriff of Falls County for nearly thirty years, a man who had stood toe to toe with the worst that society could spit up, but his voice quivered and his hands shook when he talked about Kenneth McDuff.

What really burned in the guts of the lawmen was how the system had failed so utterly, how at every juncture McDuff had thumbed his nose at authority and sent it reeling. Brady Pamplin and other Central Texas lawmen had been handling McDuff since he was a teenager, had seen flashes of his sadistic nature and his complete contempt for the rules of society. They finally put him away on a series of burglary charges in 1965, or so they thought. McDuff was assessed penalties totaling 52 years, but because he was only eighteen, the sentences were assessed concurrently instead of consecutively. McDuff made trusty in three months and was back on the street in less than ten, the smirk on his face suggesting that the time had been well spent. Eight months after he was paroled, McDuff went on one of his periodic rampages and killed the three teenagers. A jury gave him death, but after a 1972 Supreme Court decision effectively overturned all the death sentences in the United States, McDuff’s sentence was commuted to life. In 1976, ten years after the murders, McDuff had served enough time to be eligible for parole, though the parole board was certainly under no obligation to grant it—and hardly anyone supposed that it ever would.

But McDuff had time on his side. He applied for parole, and when the board turned him down, he kept on applying until he succeeded—and now law enforcement officers say that as many as nine women may be dead as a result. This spring the entire nation learned what the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles couldn’t figure out: Kenneth McDuff is an unrepentant, habitual killer. He was featured on America’s Most Wanted and became the object of a nationwide manhunt. In Texas the story of his twisted career was front-page news, especially along the Interstate 35 corridor, where he had stalked his victims. By the time he was reapprehended, Kenneth McDuff had come to personalize the violent crime wave that swept Texas in the past year—a crime wave abetted by a cynical parole policy whose aim has been to empty the prisons rather than safeguard the streets.

To gain parole from the Texas Department of Criminal Justice—as the superboard that controls paroles, pardons, and the prison system is now called—an inmate needs two votes from a three-person parole board team. In 1979 and again in 1980, McDuff got one of the two votes he needed, falling short by what must have seemed to him just a matter of bad luck. When he came up for parole the following year, McDuff tried to jigger the odds by offering a $10,000 bribe to a member of the parole board. He was subsequently tried and convicted for the bribery attempt. Despite the brutal nature of the murders, the fact that he was a three-time loser, and his bribery conviction, the parole board continued to view him as a good risk for release. In 1984 and 1985, McDuff again came within a single vote of gaining freedom. Finally, he got a second vote in 1988 and was approved for parole, but the approval was rescinded when new information was received: The parole board refuses to reveal the nature of that new information, but normally it would be letters of protest from the judge and the prosecutor at his trial. A year after that, to the shock of those same trial officials—and to law enforcement officers as well—the parole board saw fit to return McDuff to society. No, McDuff hadn’t fallen through the cracks in the system; he had slithered through, cleverly, insidiously, like a rodent in the shadows.

On the day that McDuff was let out of prison and told to report to a parole officer in Temple, where his parents had moved, Sheriff Larry Pamplin made a prediction. “I don’t know if it’ll be next week or next month or next year,” he told Parnell and Mike McNamara, “but one of these days, dead girls are gonna start turning up, and when that happens, the man you need to look for is Kenneth McDuff.” Three days later, the naked body of 29-year-old Sarafia Parker was discovered in a field of weeds in southeast Temple, beaten and strangled.

Aching to Prowl

The McDuffs weren’t the friendliest family in Rosebud when Kenneth was growing up—in fact, they were downright weird—but they weren’t white trash either. They worked hard, saved their money, and regularly attended the Assembly of God church. Kenneth’s father, J. A. McDuff, was a cement finisher who made a lot of money in the business during the building boom in Temple in the late seventies and early eighties. Addie McDuff was a large, domineering woman who ruled over her four daughters and two sons, maintained the family purse, and operated a washateria across the street from the family home, just off Main Street. Newspaper editor John Killgore recalls, “The McDuffs were very dedicated to their children, attentive, protective, making sure they grew up knowing how to work and work hard.”

Some people thought they were a little too protective. Addie McDuff and her three eldest daughters lavished attention on Kenneth and treated him as though he were a young god, somehow above the rules that restrained other children. Though Kenneth had a younger sister, he was regarded as the baby of the family. Classmates remember that Kenneth always had money in his pocket and usually wore new clothes. When he was older, his mother bought him a motorcycle that was probably the loudest machine in Rosebud. Kenneth’s father was a tight-lipped man who went about his business and left family matters to his wife, although apparently he did not share her unwavering devotion to Kenneth: When Kenneth was charged with the three murders in Tarrant County, J. A. McDuff told a lawman: “If I believed he did what you say, the state wouldn’t have to kill him. I’d do it myself.”

In the late fifties, the real troublemaker in the family was Kenneth’s elder brother, Lonnie, who once pulled a knife on the popular (and tough) Rosebud school principal, D. L. Mayo, and got thrown down the stairs for his insolence. Lonnie, who was tongue-tied, liked to refer to himself as Rough Tough Lonnie McDuff—“Wuff Tuff Wonnie McDuff,” it sounded like. While Kenneth was in prison for murder, Lonnie was shot to death by the ex-husband of a woman he was seeing.

An entry in Kenneth McDuff’s prison file notes that as a youth he was never required to assume responsibilities or observe standards of conduct, adding, “If any problem arose [at school] . . . , the school was to blame and Kenneth was completely innocent.” Any attempt to discipline Kenneth was certain to bring Addie McDuff hurrying to the school in full fury, sometimes carrying a pistol or at least claiming to. Teachers referred to her as Pistol-Packing Mama McDuff. “Every teacher in school was afraid of her,” says Ellen Roberts, a special education teacher. Many people in Rosebud had heard the story about Addie McDuff flagging down a school bus with her pistol, then giving the driver, who had thrown her son off the bus the previous day for fighting, a tongue-lashing. The story may or may not be true, but it illustrates the cloud of intimidation the McDuffs cast over the small town.

Kenneth took pleasure in bullying classmates and intimidating teachers. A classmate remembered how he would goad other kids into flipping quarters—Kenneth loved to gamble—until he had relieved them of their lunch money. Ellen Roberts recounts a strange experience when Kenneth’s sixth-grade teacher sent him to her office for consultation. “He never said a word, no response whatsoever,” she says. “He just sat there in stony silence and refused to make eye contact. That was most unusual in a young boy.”

With an IQ of 92, Kenneth was not the brightest guy in class. He liked to call attention to his negative impulses. “When he scored zero on a test,” a classmate remembers, “Kenneth would make sure everyone in class knew about it, make some kind of joke just to let everyone know he did it on purpose and didn’t give a damn.” What this classmate remembers most is McDuff’s maniacal laughter, usually at something that no one else thought was funny, and how, in an instant—“like turning a light on and off”—the laugh would dissolve into a glare so hard and cold it stopped conversation.

People who grew up in Rosebud with Kenneth McDuff recall with enormous satisfaction that day in the eighth grade when McDuff challenged Tommy Sammon to meet him after school. Tommy was one of the most popular boys in school, a good athlete, modest, unassuming, not easily provoked. McDuff had been trying to goad him into a fight. He finally succeeded one day between classes, bumping against Sammon in the hallway and calling him a chickenshit in front of his friends. Ellen Roberts says, “Kenneth was so hated that when word got around that he was going to fight Tommy Sammon after school down by the drainage ditch, my whole class talked of nothing else.” The fight, such as it was, lasted only a few minutes. Though McDuff was larger than Sammon—or almost anyone else in school—Sammon easily overpowered him. McDuff was big, but he wasn’t strong. Sammon got him in a headlock, and McDuff bit him. The incident went down in Rosebud history as the day Tommy Sammon liberated the town (or at least the eighth grade) from the bully McDuff. Kenneth never bothered Sammon or anyone else in his class after that. A few months later, he quit school for good and went to work for his father.

The only close friend Kenneth had, either before or after he dropped out of school, was his brother, who listened to the stories of how society had mistreated Kenneth and counseled him on the proper response—screw ’em, was Lonnie’s advice. Sometime in the fall of 1964, when Kenneth was about seventeen and spending his evenings breaking into buildings and prowling for sex, he confided to Lonnie that he had raped a woman, cut her throat, and left her for dead in a ditch. Lonnie told him to go to bed and forget it. Not long after that, McDuff was sent to prison for burglary. The rape and attempted murder were never reported; otherwise the parole board might not have looked so casually on McDuff when it decided to release him in December 1965.

Kenneth McDuff underwent a subtle but deadly change following that first parole. The belief that he had committed murder and gotten away with it—coupled with the short, easy prison term he served for pulling more than a dozen burglaries—hardened him, gave him an exaggerated sense of invulnerability. He wasn’t a boy any longer; he was a man, having grown to six feet three inches and two-hundred-plus pounds, his broad shoulders and large hands causing him to look even larger. The evil of his countenance was accented by a crooked smile and a bulblike Popeye nose. Though prison had not taught McDuff how to make friends, it had taught him how to attract smaller, weaker sidekicks who could be controlled through intimidation and counted on to take part in whatever twisted schemes appealed to McDuff’s appetites. Kenneth seemed to enjoy having a witness to his debauchery.

One such unfortunate companion was Roy Dale Green, who lived with his mother in Marlin and worked for Kenneth’s dad. Green was two years younger than Kenneth and was mesmerized by McDuff’s tales—and sometimes exhibitions—of sadistic sex: One of McDuff’s more brutal amusements, which he demonstrated once in a bedroom of Green’s mother’s home, was pinning a girl to the floor and squirting a tube of Deep Heat into her vagina. Kenneth bragged that he had raped and strangled several women in his time. “Killing a woman’s like killing a chicken,” he told Green. “They both squawk.” Green wasn’t certain that he believed McDuff—until the evening of August 6, 1966.

It was a Saturday and McDuff was aching to prowl. He and Green had worked that morning pouring concrete at a construction site in Temple, and after work they cleaned up and headed for Fort Worth in the new Dodge Charger that McDuff’s mother had given him when he got out of prison. Green, who was eighteen at the time, had never been to Fort Worth, but McDuff had worked there a few years earlier and said he knew some girls. They cruised the small town of Everman, just south of Fort Worth, drinking beer and visiting with friends, including a girl that Kenneth knew from church. Later that evening, after they had taken the girl home, Kenneth found what he was looking for—a pretty teenage girl in a red-and-white-striped blouse and cutoff jeans—a total stranger, standing near a baseball field talking to two boys in a 1955 Ford. Purely by chance, McDuff selected his three victims—sixteen-year-old Edna Sullivan, her boyfriend, seventeen-year-old Robert Brand, and Robert’s cousin, fifteen-year-old Mark Dunnam, who was visiting from California. Roy Dale Green watched with fascination as McDuff took a .38 pistol from under his car seat and walked over to the three young people. First, McDuff demanded that the boys hand over their billfolds, then he forced all three into the trunk of the car and locked them in. “They got a good look at my face,” he told Green. “I’ll have to kill them.”

McDuff drove the Ford, with the teenagers in the trunk, down dark and narrow country roads, and Green followed in McDuff’s Dodge, still not convinced that McDuff intended to harm his hostages. Presently, McDuff turned into a field and stopped. He opened the trunk and said, “I want the young lady out,” pulling her by the arm. He instructed Green to lock her in the trunk of the Dodge, which Green did. Still in the trunk of the Ford, the two boys were on their knees, begging for their lives, when McDuff brought the gun up to chest level and shot them both in the face. He shot Brand twice and Dunnam three times, then lifted Dunnam by the hair and shot him again. Green saw the fire from the gun and covered his ears, looking away from the horror but not before seeing the look on McDuff’s face, an expression of inner peace that seemed to say, How do you like it so far, Roy Dale? For some reason the trunk wouldn’t shut, so McDuff backed the Ford, with the trunk open, against a fence, then McDuff and Green drove away in the Dodge, the terrified Edna Sullivan still a prisoner in the Dodge’s trunk.

With McDuff driving, they headed south, crossing the Johnson County line, eventually stopping along a dirt road about eleven miles from where they had left the Ford with the boys’ bodies. McDuff took Edna Sullivan from the trunk, made her undress, then threw her in the back seat and began raping her. He raped her two times, made Green rape her, then he raped her again. In all this time, Green heard the girl say just one thing: “I think you ripped something,” she cried out as McDuff brutalized her for the third time. His sexual appetite momentarily in check, McDuff drove them to another location, down a gravel road. Stopping, he took the girl to the front of the car and told her to sit down on the road. Green wasn’t sure what McDuff had in mind. Then he saw McDuff force the girl’s head to the ground and begin choking her with a section of broomstick. “He mashed down hard,” Green told lawmen. “She started waving her arms and kicking her legs, and he told me, ‘Grab her legs.’” While Green held Edna Sullivan’s legs, Kenneth McDuff crushed the life out of her. Then they threw her body over the fence and headed home, stopping along the way to bury the boys’ billfolds and discard their own bloody underwear.

Roy Dale Green never fully recovered from the horror of that night. The next afternoon, while he was taking a Sunday ride with friends, news of the killings came over the radio and suddenly Green was blurting out the whole story. “My God, I’ve got to tell somebody!” he cried. He became the prosecution’s star witness in the case against Kenneth McDuff, served five years for his part in the crimes, and returned to Marlin, where he lives to this day. “He stays out at the old family home and spends most of the day in his sister’s beer joint, the Town Door,” says Sheriff Larry Pamplin, who has known Green all his life. “To say he’s messed up is a real understatement.”

Vowing Kenneth’s innocence, Addie McDuff hired a lawyer from Waco and sat in the courtroom with her daughters throughout the trial. McDuff denied any knowledge of the killings, of course, suggesting that Roy Dale Green was probably responsible and, in an aside to the jury, whining that Falls County sheriff Brady Pamplin had had it in for poor Kenneth McDuff for years. During one recess, Mama McDuff told reporters that Kenneth had been with a girl from his church at the time the three teenagers were murdered, that her son was willing to risk death in the electric chair to spare the girl’s reputation. “He’s too good for his own good,” she said.

Justice for McDuff, Inc.

Two times in 1969 and again in April 1970, Kenneth McDuff came within a few days of his execution date, and each time he was granted stays. McDuff probably wasn’t sweating it. Only a handful of executions had taken place in the United States in the two years before he was convicted and none in the time he had been on death row. And the case of Furman v. Georgia was working its way through the system. In 1972 the Supreme Court handed down its landmark decision, ruling that the unlimited discretion given to juries in capital trials—the ability, for example, to sentence someone to death without first focusing on the particular nature of the crime and the particular characteristics of the accused—amounted to cruel and unusual punishment and thus was unconstitutional. In effect, all the capital convictions in the country were overturned. Within a few months, the death sentences of all 88 inmates on death row in Texas were commuted to life.

McDuff was transferred to the Ramsey Unit and assigned to work in the fields, which was where prison officials put inmates who needed the tightest supervision. “We considered McDuff to be extremely dangerous and a high escape risk,” says David Christian, who was an assistant warden at the unit in the seventies.

In 1977, Addie McDuff hired a new lawyer, and the Kenneth McDuff story took on the trappings of a Hollywood melodrama. A Dallas attorney named Gary Jackson began a long and costly effort to prove that McDuff had been framed and that the true killer was his evil running mate, Roy Dale Green. Over the next decade, Kenneth McDuff became more than merely a client for Gary Jackson; he became an industry, incorporated in 1989 under the name of Justice for McDuff, Inc. There was, until recently, talk of book and movie deals. Jackson, who refused to be interviewed for this article and no longer represents McDuff, seemed a curious candidate to lead the McDuff crusade—he and his wife were both active in the Republican party of Texas, and Jackson had a career in the U.S. Army Reserve, where he now holds the rank of colonel. He didn’t usually practice criminal law. Nevertheless, Gary Jackson became a zealous advocate for the convicted killer. Poring through old trial records and newspaper accounts and crossing the country to interview witnesses, Jackson devised a new scenario for the events of August 6, 1966.

In a 26-page, single-spaced letter written to the chairman of the Board of Pardons and Paroles in 1979, Jackson presented what he considered dramatic new evidence. At the trial thirteen years before, McDuff had testified that on the night of the killings he handed over the keys to his new Dodge Charger to Green so that Green could go on a date. In the revised version, Gary Jackson claimed that Green needed the car to pull a robbery—the implication being that McDuff wanted no part of the robbery but had no objection to loaning his car to Green. In both versions McDuff had waited for Green in a burned-out shopping center in Everman, napping while Green satisfied his lust for murder. The problem, of course, was how Green could have driven both the Dodge and the Ford.

To get around this apparent impossibility, the lawyer developed a theory in which Green rendezvoused with the teenagers, whom he had met earlier that evening, to do some “underage drinking” in the field where the boys’ bodies were later discovered. Running out of beer, Green and his new friends left the Dodge in the field and took the Ford to buy more, which they consumed at the second location—the spot in Johnson County where Edna Sullivan’s body was found. There, Green made his move. Forcing the boys into the trunk at gunpoint, he proceeded to rape Edna Sullivan. While Green was occupied, the boys forced open the trunk. Realizing the impending danger, Gary Jackson wrote, Green “jumps out of the car and, without thinking, shoots the boys . . . using all six shells in his pistol.” The six shots were a nice dramatic touch—it always is in the movies—because it meant that Green was out of bullets and had no choice except to strangle Edna Sullivan with a broomstick. He leaves her body there and returns the Ford, with the two dead boys in the trunk, to the first location, where he picks up the Dodge and heads for the shopping center where McDuff has been waiting. This scenario had the added advantage of placing all three murders in Johnson County, out of the jurisdiction of the judge and jury that found McDuff guilty in the first place.

Gary Jackson’s letter impressed at least one member of the parole board enough to vote for McDuff, but it did not result in a parole for his client. In 1980 the Dallas attorney came up with additional evidence, alleging in a writ of habeas corpus several incidents of jury misconduct and tampering. Rumors of improper conduct had first surfaced back in 1966 in a newspaper report that one of the jurors had carried a flask of “needful intoxicant” into the dorm where the jury was quartered and in a story in the old Fort Worth Press, alleging that the sheriff of Tarrant County had come to the dorm and told jurors about another crime that he believed McDuff had committed. This one involved a rape and disfigurement, and the sheriff supposedly told jurors that because of “stupid” laws, they hadn’t been permitted to hear about it. The story had been leaked to the media by a bailiff named Rose Marie Anderson, who had vanished after the trial, claiming that she had been threatened by the sheriff for speaking up. Gary Jackson tracked the ex-bailiff to Arizona, where she repeated her allegations in an affidavit. Jackson was able to get McDuff an evidentiary hearing in Fort Worth in 1982, but the court found the allegations not worthy of belief. During that same time period, McDuff wrote several letters of his own, one of them to the Court of Criminal Appeals in Austin, reporting a rumor that his trial judge in Fort Worth had taken $750,000 from the Mafia.

“My Family’s Got the Money”

In his six years on death row and his seventeen years among the general prison population, Kenneth McDuff wasn’t necessarily a model prisoner, but he knew how to keep his shirt clean. Hard cases like McDuff are given maximum leeway: As long as they are not putting a knife into someone or openly smuggling drugs, they can do almost what they please. After transferring to the Retrieve Unit, near Angleton, McDuff became boss of his tier of cells. In that position, a man of McDuff’s talents would have enjoyed not only the blessing of the wardens but substantial clout among inmates, meaning, among other things, that McDuff was able to influence which inmate was assigned as his cell mate. While McDuff was at Retrieve, his cell mate—or punk, to use the vernacular—provided whatever McDuff required in the way of sex and drugs, which he squirreled away in a red balloon inserted up his rectum—keistering drugs, they call it. Not your garden variety punk, this particular one was large and cold-eyed, with an excess of body hair and tattoos, but his menacing appearance was handicapped by the fact that he had offended the Aryan Brotherhood and faced the daily threat of assassination. It was a measure of McDuff’s prestige that he was able to protect his punk without tarnishing his own good record.

Mastering the angles came naturally to Kenneth McDuff. The parole board looked favorably on inmates who tried to better themselves—so this eighth-grade dropout enrolled in correspondence courses. If there was a shift in policy, or a subtle trend among parole board members, McDuff was one of the first to sniff it out. The procedure for considering which inmates deserved parole was—and is—for one of the three members of the parole team to interview a batch of inmates (usually fifteen to twenty in a single day) as they become eligible, then vote yes or no on each one and pass the files to the second member. Most of the time the members don’t even bother to discuss the cases with each other. In the early eighties, during Bill Clements’ administration, the governor had to approve paroles, which is no longer the case. Scuttlebutt among prisoners held that if a Clements appointee voted yes on an applicant that he had personally interviewed, at least one of the other members was likely to go along and so was the governor.

When McDuff’s name came before the parole board in 1980, he received the vote of one member, Helen Copitka, who had been a parole commissioner since 1975 (before 1989 both commissioners and board members voted on parole). Copitka was swayed by the material that attorney Gary Jackson had sent to the parole board. Copitka was still on the board in 1981, but McDuff asked to be interviewed by Glenn Heckmann, who had been appointed by Governor Clements in January 1980. As soon as he was alone with Heckmann in the chaplain’s office, McDuff said, “If you can get me out of this pen, I guarantee that $10,000 will be left in the glove compartment of your car. I know you’re the governor’s man. Word is, I get your vote, I’m out of here. My family’s got the money.” Heckmann mumbled that he would take McDuff’s offer under advisement and went straight to the office of the Brazoria County district attorney, who filed a charge of bribery against McDuff.

The charge resulted in McDuff’s third conviction, which meant that the jury had an opportunity to give him life under the state’s old habitual felon act; another life sentence would have pushed McDuff’s eligible parole date into 1992. Instead, McDuff (with help from Gary Jackson) once again displayed his uncanny talent for slithering through the system. Over the objection of prosecutor Ken Dies, the judge granted McDuff considerable latitude to tell the jury about his criminal past—not the details of his murder spree in 1966, but his own fantasy of how the system had conspired against him, time after time, injustice heaped upon injustice, the good name of “McDuff” besmirched by charlatans. It was a soliloquy of soap opera proportions, and McDuff carried it off with a straight face.

Under the provisions of the habitual felon act, the jury first voted on McDuff’s guilt or innocence in the charge of bribery; that part was easy. The law then called for a separate deliberation, one that was strictly technical, in which the jury was required to find that the Kenneth A. McDuff they had just found guilty was the same Kenneth A. McDuff that two previous juries had found guilty. But the jury misunderstood the instructions. “They got confused by McDuff’s testimony, which was partly my fault,” Ken Dies admits. “They thought that they were supposed to rule on McDuff’s guilt or innocence in the two previous cases.” Of course, the jury couldn’t be sure, since it didn’t hear the evidence in those cases. So instead of giving McDuff life, the jury opted for two years—a meaningless punishment, since McDuff had accumulated more than two years of good time merely waiting for his trial. In effect, McDuff offered a bribe to a parole officer and got away with it.

So why did a 1989 parole board—fully aware of McDuff’s criminal history and cognizant that the jury that found him guilty of murder also found that he was likely to kill again—decide to put him back among us? The quick answer is that by 1989 Kenneth McDuff was no longer a name or even a case history; he was just a number. Two years before, Bill Clements, the parole board, and the prison system had decided that to prevent Texas prisons from becoming overcrowded in violation of court-imposed ceilings, 750 inmates a week had to be paroled. That meant the fifteen members of the parole board (the number was elevated to eighteen in 1989) had to interview and study the files of at least 1,000 inmates every five working days. Old-timers like McDuff, convicts whose names came up year after year, weren’t even interviewed anymore but were lumped with similar inmates in special review groups. Their files—if board members bothered to study them at all—contained only the most basic and banal information, hardly anything to suggest the true nature of an inmate. By the time McDuff was paroled, eight of every ten parole applications were being approved, and the system was still falling behind. All the good risks for parole had been exhausted; the parole board was getting down to the bottom of the barrel. And then the bottom was lowered: Time was awarded so liberally that an inmate could get credit for serving one full year in just 22 days. In a prison system with a capacity of 60,000 inmates, more than 36,000 received paroles in 1989, the year Kenneth McDuff went free. The goal of the state became not to keep the streets safe but to keep the tap flowing and the federal courts at bay.

Chris Mealy, the parole board member who cast the deciding vote that freed McDuff, recalls that when McDuff came up for special review in September 1989, he was impressed by two things. First, McDuff had begun to improve himself by taking college-credit courses, and second, the file showed that in six of the fifteen years since he had become eligible for parole, McDuff had received one affirmative vote. In hindsight, Mealy admits that maybe he made an error: “If any of what we know is true, then obviously a mistake was made. It’s a human system. Errors will be made. Some of them will be very costly. I wish that I could take it back.”

But in the case of Kenneth McDuff, the parole board blew it not once but twice. In July 1990, nine months after he was released, McDuff was charged with a new crime, making a terroristic threat—a misdemeanor, but also an offense sufficient to put him back behind bars for the remainder of his life, because it was committed while he was on parole. The charge grew out of a racial incident in downtown Rosebud. McDuff directed some slurs at a group of black teenagers who were minding their own business, then chased one of them down an alley with a knife and threatened to kill him. At his preliminary parole revocation hearing, McDuff spewed forth his loathing for blacks with such intensity that Gary Jackson had to shout at his client to prevent him from doing additional damage to his claim of innocence. McDuff was returned to TDCJ in September, but once again the system faltered. After conferring with Sheriff Larry Pamplin, Falls County district attorney Tom Sehon made the fateful decision to drop the misdemeanor charge—most of his witnesses were too frightened to testify, anyway—and allow the parole board to deal with McDuff. To make sure the board understood that the people who knew McDuff best considered him a continuing menace, Sehon wrote a letter in which he called McDuff “the most extraordinarily violent criminal ever to set foot in Falls County” and advised the board against ever reinstating McDuff’s parole.

Nevertheless, Gary Jackson filed a motion to have McDuff’s parole reinstated. He made the point that the charge that had caused it to be revoked had been dismissed. What happened next was bureaucracy at its worst. The board had long considered the revocation and reinstatement process a waste of time and, for years, had delegated to its staff (known as hearings officers) the power to revoke and reinstate paroles, even though some lawyers believe that the practice is illegal. There was no hearing, no testimony, no advocacy of any kind. The board made no formal decision to reinstate McDuff’s parole. Some anonymous hearing officer simply decided that there was no reason to keep Kenneth McDuff locked up. On December 6, 1990, Kenneth McDuff went free again.

“Please, Not Me!”

Sheriff Larry Pamplin and his friends in the U.S. marshal’s office in Waco, the McNamaras, sensed that McDuff was back on the prowl long before they could prove it. “The most frustrating part,” says Pamplin, “is that we knew he was going to kill someone. We just didn’t know when or where.” In any case, it wasn’t clear what they could do about it. Unless McDuff committed a crime in Falls County, Pamplin wouldn’t have jurisdiction, and the only way the McNamaras would be able to investigate would be if McDuff became a federal fugitive. Still, the three lawmen did what they could to keep track of McDuff. In the beginning, at least, McDuff was cool enough to keep on the good side of his parole officer, and no other law enforcement agency seemed at all interested in his activities.

McDuff moved frequently—Temple, Rockdale, Cameron, Bellmead, Tyler, Dallas—usually staying close to his mother or one of his sisters, most of the time with no apparent means of support, driving new cars, spending freely, robbing crack dealers on the street. The randomness of his movements made connecting him with specific murders almost impossible for Pamplin and the McNamaras. They didn’t even learn about several of the killings McDuff is now suspected of committing until weeks after the fact.

In the spring of 1991, McDuff enrolled in Texas State Technical College in Waco and moved into a dormitory on campus. Starting then, and in the months that followed, several Waco-area prostitutes were reported missing, a fact that didn’t appear to alarm Waco police or prompt them to ask hard questions of McDuff. A woman named Regenia Moore was seen kicking and screaming in the cab of McDuff’s red pickup truck as it ran through a police checkpoint, and though the police did look up McDuff several days later and question him, nothing came of the incident. He seemed to be living a charmed life; he beat up and nearly blinded a fellow student at TSTC and threatened several others, and still nobody reported him to the police. It was a cool life: student by day, drug-crazed prowler by night, nobody asking questions.

Then, a week before he was scheduled to take his final exams, McDuff abandoned all pretense of cool. Sometime late on the evening of March 1, 1992, he parked his tan Thunderbird at the New Road Inn just south of Waco and vanished into the shadows. That same night, less than a block away, 22-year-old Melissa Northup was kidnapped from a convenience store where she worked. Her body was found weeks later, bound and floating in a gravel pit in Dallas County, near the spot where the killer had left her car. A few weeks after Northup’s disappearance, police discovered the naked and badly decomposed body of Valencia Kay Joshua in a shallow grave in a wooded area behind TSTC. Joshua was one of the missing prostitutes. She was last seen alive on the night of February 24, on the TSTC campus, looking for McDuff’s dormitory room. McDuff’s sudden disappearance caught the parole board and everyone else by surprise. Addie McDuff was so worried that she filed a missing persons report.

Knowing McDuff’s history, the McNamaras realized they had to act quickly, and for once, the system cooperated. McDuff had made a mistake that played into the hands of the law: He had sold drugs to an informant. Using information provided by two informants, assistant U.S. attorney Bill Johnson of Waco charged McDuff with possession of firearms and distribution of drugs. McDuff had unwittingly become a federal fugitive, which was all the McNamaras needed to get on his trail. The U.S. Marshals Service had already assigned 250 investigators to Operation Gunsmoke, a nationwide effort to target violent offenders and get them off the streets. McDuff fit the mandate of Operation Gunsmoke right down to his evil smirk.

By early March, a formidable Kenneth McDuff task force had been assembled in Waco. It consisted of lawmen from several county and local police departments, agents from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms and the Drug Enforcement Agency, Texas Rangers, an investigator from the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, and about two dozen federal marshals from Operation Gunsmoke, including two of the agency’s international supersleuths, Mike Carnevale of San Antonio and Dan Stoltz of Houston. Capturing McDuff was becoming a national priority. “Until I actually got on the scene down in Texas,” says Mike Earp, a supervisory inspector of the Marshals Service’s enforcement division in Washington, D.C., “I didn’t realize what an impact McDuff had had on those small communities, that people were absolutely terrified of the man.” Earp, a distant relative of the most famous marshal of all, Wyatt Earp, dispatched one of the service’s mobile command centers, a double tractor trailer rig called Red October. Parked on the lot behind the federal building in Waco for the duration of the search, Red October put the task force in communication with every law enforcement agency in the country. It seemed somehow appropriate that the job of tracking down one of the worst killers in modern times should fall on the Marshals Service, the oldest law enforcement agency in the country, founded in 1789 by George Washington. It seemed appropriate, too, that Parnell and Mike McNamara (assisted by another Waco-based deputy, Alonda Guilbeau) should take the point in this deadly race against time.

Many of McDuff’s ex-convict running mates lived in Temple and nearby towns, so that’s where the task force focused its search. Layer by layer, McDuff’s sordid past was overturned. In the community of Holland, they questioned some people whose family album consisted almost entirely of photographs taken at TDCJ. One marshal said matter-of-factly that one of the boys told them that after his daddy killed his mama, “the old man had only stabbed him once and beat him twice with a tire tool.” A major shock was the discovery that Kenneth McDuff had a daughter. The woman that he raped and left for dead in 1964 not only survived but also had his baby. The daughter, Theresa, was 21 when she learned that her real father was a convicted killer named Kenneth McDuff. Theresa told the marshals that she had visited McDuff in prison and became fascinated by him. He tried to persuade her to smuggle drugs. After his parole, McDuff offered to take her to Las Vegas and be her pimp. She also told the marshals that McDuff’s family had paid $25,000 to a former member of the parole board to secure his release from prison in 1989, an accusation that has led to an ongoing investigation of several former parole board members. Disenchanted with the man she once found so fascinating, Theresa has moved out of state, as far from Kenneth McDuff as possible.

At first McDuff’s associates were too loyal—or maybe they were simply too frightened—to give up much information. The McNamaras developed a technique for softening them up. They would launch into a bloody description of McDuff’s murder spree in 1966, watching the reaction as the story spilled out. Sure, his friends knew from being in prison that McDuff had killed some people, but nobody inside went into details: They didn’t realize that there were three of them, that they were kids, for Christ’s sake, that the boys had begged on bended knees as McDuff blew off their faces, that Edna Sullivan’s eyes had filled with terror as McDuff leaned his full weight onto the broomstick pressed across her throat. The story always got a reaction, even from the sorriest of criminals.

The search was as arduous as it was intense, requiring the lawmen from the various agencies to pull eighteen-hour shifts, usually without a day off. Sometimes they didn’t bother going back to their motel room to sleep, curling up instead on the floor of the marshal’s office in Waco for a few hours. But piece by piece, they began putting things together. The first big break came when they cornered McDuff’s onetime punk in the parking lot outside of Por Boy’s Lounge in Temple. After some persuasion, he told them about a woman drug dealer in Harker Heights, who in turn directed them to a thug in Dallas, who told about spending Christmas Day with McDuff in Austin. This was an especially interesting revelation because it established that McDuff had been in the Capital City five days before 28-year-old Colleen Reed was abducted from a car wash west of downtown. Witnesses had reported that two men in a tan car with rounded taillights—a good description of McDuff’s Thunderbird—had grabbed Reed and sped off, going the wrong way on West Fifth Street. Driving the wrong way on one-way streets was a McDuff trademark, one of the many ways he demonstrated his contempt for the rules of society. The Austin police were under enormous public pressure to solve the Reed case, but they had dismissed McDuff as a suspect because, according to their sources, McDuff hadn’t been in Austin since October.

But the McNamaras were sure that McDuff was their man. They began running through a list of McDuff’s buddies, looking for someone who fit the description of the second occupant of the tan car—a Hispanic or dark-complected white male. They stopped at the name of Alva Hank Worley. A 34-year-old concrete worker who hung out with McDuff, Worley fit the description fairly well, but more than that, he was a textbook example of the kind of weak-willed sidekick McDuff liked to have around. They saw Hank Worley as a nineties version of Roy Dale Green, a man haunted by what he had done, a man ready to talk.

Worley lived with his fourteen-year-old daughter at Bloom’s Motel, south of Temple, and late one night the McNamaras, along with a deputy from the Bell County Sheriff’s Department, knocked on his door. The late hour was calculated for maximum psychological effect. They didn’t expect much out of Worley on the first visit and that’s what they got: He claimed that he barely knew Kenneth McDuff. When Mike McNamara went into his bloody account of McDuff’s murder spree, Hank Worley didn’t blink. “That was not a normal reaction,” Mike told his brother as they drove away. “He knows something.”

Over the next two weeks, the marshals and the deputy dropped by Bloom’s Motel at odd hours, always taking Worley by surprise—what lawmen call “driving a suspect up.” One thing Mike McNamara had learned in his 21 years on the job: Criminals are basically lazy, you drive them up by outhustling them, by working while they’re sleeping (or trying to), by imprinting on their brains the relentlessness of your pursuit and the hopelessness of their attempts to outrun or outlast it. On the fifth visit, several marshals found Worley barbecuing and drinking beer with some friends. Over Worley’s shoulder, Mike McNamara could see Worley’s young daughter, and he kept his eyes on her as he began his litany: “Hank, you’re hiding a kid killer, you know that? You’re protecting a man who raped and brutalized and strangled a girl not much older than your daughter over there. Picture her on the ground, a broomstick across her throat, crying out to you for help, begging you to speak out, to do what’s right, to save the life of some other young girl, to . . .” About that time Hank Worley began to scream.

When Worley had calmed down, this is the story he told: Four days after Christmas, he rode with McDuff to Austin to look for drugs. They cruised the university area and scouted the bars on Sixth Street; then they crossed Lamar and turned south on a side street to double back in the direction they had come. That’s when McDuff spotted Colleen Reed, washing her black Mazda in one of the bays at the car wash on Fifth. She was a random choice, just as Edna Sullivan had been in 1966. McDuff parked his Thunderbird in the adjacent bay and disappeared for a moment. When he returned, he had Colleen Reed by the throat, holding her up so that just her toes touched the cement floor. “Please, not me,” she cried. “Not me.” McDuff threw her in the back seat and put Worley back there to control her.

A few miles out of Austin, McDuff pulled over and changed places with Worley. While Worley drove along I-35, McDuff stripped Colleen Reed naked, stubbed out a cigarette between her legs, and began raping her. When Worley stopped again to change places, he noticed that her hands were tied behind her back. While McDuff drove, Worley took off his own clothes and forced her to perform oral sex. Then he raped her. North of Belton, McDuff turned off the interstate onto Texas Highway 317, close to the house where his parents lived. He stopped on a narrow dirt road and raped Colleen Reed again.

When she was able to stumble to her feet, the young woman put her head on Worley’s shoulder and said in a quivering voice, “Please don’t let him hurt me anymore.” McDuff grabbed her by the back of the neck, shoved her into the trunk of the Thunderbird, and slammed it shut. When McDuff dropped Worley off that night, Worley asked what he intended to do with the woman. “I’m gonna use her up,” McDuff grinned. That was one of McDuff’s pet phrases: It meant that he intended to kill her. Police believe that McDuff buried Colleen Reed in a field a few hundred yards from the frame house where J. A. and Addie McDuff live, but her body hasn’t been found.

Worley’s statement was released to the media, giving the McDuff task force what it needed most—national attention. On May 1, America’s Most Wanted featured the search for Kenneth McDuff, generating fifty tips. Three days later, Kansas City, Missouri, police received a call from a viewer who had suddenly realized that a womanizing garbage truck worker known as Fowler was in fact a killer from Texas named McDuff. A few hours later, at the city dump, McDuff surrendered without a struggle.

While the investigation continues, authorities believe that McDuff may have killed as many as nine women, going back to Sarafia Parker, whose body was found near Temple three days after he was paroled. He has been charged with capital murder in Waco in the deaths of Valencia Kay Joshua and Melissa Northup, and almost certainly will be charged with the kidnapping and murder of Colleen Reed. Federal and state prosecutors are discussing the appropriate way to deal with McDuff, but they are in general agreement that the prosecutor who can make the best capital case should get the first chance at him. This time, God willing, the system will do the right thing. If there has ever been a good argument for the death penalty, it’s Kenneth McDuff.

- More About:

- Longreads

- Crime

- Gary Cartwright