Playing a show at Liberty Lunch was like playing in any other former lumberyard. The stage was wide and sagged in the middle. There was a partial roof over a concrete floor, where people stood or sat at weathered picnic tables. The bathrooms always seemed to be in a state of transition. Across the street was an abandoned warehouse, next door on one side was a boarded-up nineteenth-century general store, and on the other was a homeless center.

It was the coolest club in town. The Lunch had opened in 1975 and started off as a reggae place, which would explain the mural on the wall of a hippie raising his child above the waters of a river that poured from a giant coconut. In the eighties and nineties, bookers Mark Pratz and Jeanette Ward brought in punk, metal, blues, country, folk—whatever. They had Nirvana, Run-DMC, and Oasis on their ways up; Dolly Parton, King Sunny Ade, the Pogues. The Neville Brothers and Joe Ely did live albums there.

I first played there in 1982 with my band the Soul Bashers, and then did dozens of shows there with Wild Seeds, including our final one in 1989 to a packed house of a thousand people. I bartended there, did security, did drugs, had sex down the hill by the river. It was wide, open, shaggy. It felt like Austin. The Lunch was as essential to the growth of the music scene and the city’s identity as a music mecca as any club since the Armadillo World Headquarters, which closed in 1980. As the Fillmore was to San Francisco and CBGB’s was to New York, the Lunch was to Austin.

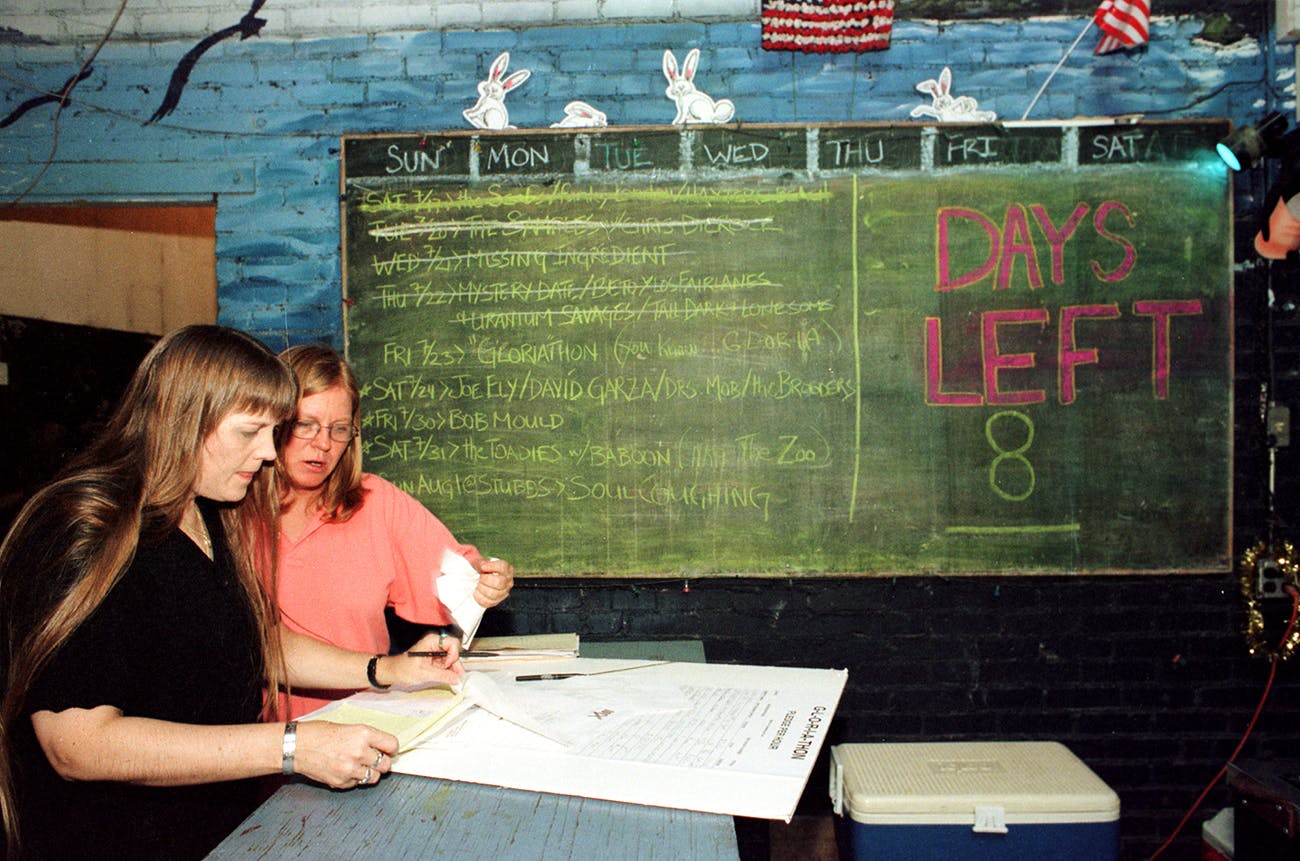

So when owners Pratz and Ward announced the Lunch had lost its lease and would be closing at the end of July 1999, we knew we were losing something special. I came up with a way to celebrate the club and to say goodbye to an era. We would drink, we would laugh, we would cry.

We would play “Gloria” for 24 hours straight.

“We” would be my band the Brooders and as many musicians as we could find who had played the Lunch over the years. We would play the song together, defiantly. “Gloria” is one of the primeval documents of rock and roll, one of the songs every kid with a guitar learns to play, a celebration of youth, simplicity, and the power of three chords. For a goodbye to the Lunch, it was perfect. Plus it has one of the most anthemic choruses of all time: “G-L-O-R-I-A, Gloria!”

The one rule: musicians could come and go onstage but somebody had to keep the beat going. I called up friends and musicians I didn’t know and asked them to come play. It’ll be fun, I said. I’ll see, they replied. Some outright refused (one insisted on doing “Louie Louie” instead) but most laughed and said they’d stop by. Blues bassist Sarah Brown—one of the best players in town—said to sign her up for ten minutes.

We set up two drum kits, several guitar amps, a bass amp, a couple of keyboards, and several vocal microphones. The Brooders started at 9 p.m. on Friday, July 23. We began quietly, with bass, vibrato guitar, no drums for fifteen minutes. After a while I started singing those iconic first words, “Like to tell ya ’bout my baby . . . ” I figured we had a ways to go, so we free-associated for a while on the song’s basic chords: E-D-A. We finally hit the chorus after an hour of dicking around and it felt like a holy release. “Gloria!”

Then we went back to the verse, vamping on those chords: E-D-A. E-D-A. The song burbled along for six minutes or so then began picking up in intensity, the band playing as one, everyone straining for that release again: “Gloria!”

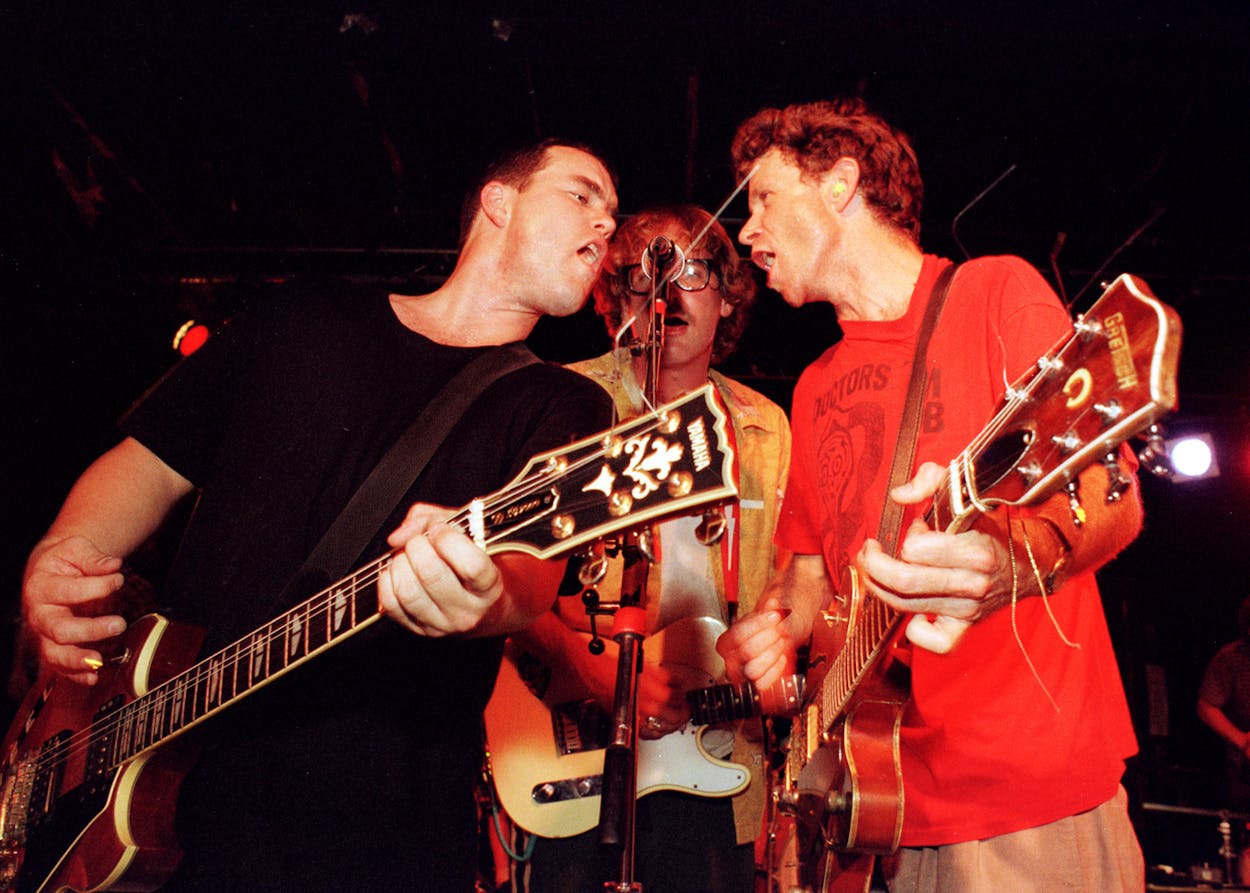

Then back to the verse. Soon we were lost in the hypnotism of repetition. It was like trance music. E-D-A. E-D-A. E-D-A. After a couple of hours, various Brooders began leaving the stage as replacements arrived to take our places. They would play for thirty minutes or an hour—and not want to leave the stage. It was addictive, playing the same thing over and over, feeling the rush of anticipation as we moved toward the chorus, hitting it—and then starting all over again. Sarah came and started playing and stayed up there for a half hour. Others got up and stayed for two or three hours. Guitarist Kevin Carroll would play for six.

Different players gave different feels. Barbara K, one half of indie pop stars Timbuk 3, took the song in a reggae direction. Terri Lord, a drummer for local punk bands since the early eighties, played completely differently than Mark Patterson, the drummer for Kelly Willis’s band. Kevin McKinney was a groove guitarist with Soul Hat while Steve Collier was a pop guy with the Sidehackers. Guitarist Carroll was a lyrical lead player, while Brent Grulke bashed the strings of my Gretsch so hard he cut open his fingers, spraying the guitar with blood.

Various vocalists sang Morrison’s words or made up their own verses. Folk singer Gretchen Phillips channeled Patti Smith; punk rocker Tex Edwards channeled Jim Morrison. There would be long stretches where no one sang and we just played the same three chords: E-D-A, feeling the simplicity, the repetition. Then the singer would start picking it up and so would the players, and everyone could feel the anticipation build, he or she would get more agitated, leading into the spelling out of her name and the band would start playing louder, culminating in the glorious cathartic chorus, a dozen musicians screaming on stage and a couple dozen people in the audience singing along. It didn’t matter how many times the chorus came around—every time it was fresh, wild, transcendent. Every time it was new.

Musicians began leaving around closing time, but others showed up. There were some bleak hours before the dawn, but the skeleton crew pushed on. E-D-A. E-D-A. A guy from India played drums for three hours from 2 a.m. to 5 a.m., then passed out backstage. Singers were especially scarce, and occasionally an audience member would jump onstage and sing a few verses. Brian Zoric, the Brooders’ bass player, left around 4 a.m. and I took over. I loved the simple repetition of the basic riff. Around 5 a.m., music journalist Ken Lieck stood onstage and played a tape of English alternative rock guru Robyn Hitchcock, whom he had interviewed the day before. “You are eight hours into the Gloriathon,” Hitchcock said. “You have sixteen to go. Thank you.”

A few people who ran another club in town showed up high on drugs and took over the stage, singing and screaming and energizing us. At about 6 a.m., I lay on my back and looked up through the open roof past the red and green stage lights. I watched the sky slowly begin to lighten, birds flying past. Time was passing, the Lunch was dying, we were still playing. A few minutes after 7 a.m., Ward walked onstage with a tub of Lone Stars. Bar’s open! We toasted each other with one free hand and kept playing.

I had hoped to stay all 24 hours, but beer for breakfast pushed me over the edge. At 8 a.m. I drove home to take a nap. I slept hard for a few hours and rushed back at 11:30 a.m., sure that the whole thing would have died without me there to watch over it. As I drove north, crossing the river on the South First Street bridge, I heard the familiar chords and melody bouncing off the empty warehouses, like the city itself was playing the song. It was one of the most beautiful sounds I had ever heard. I walked in and there were ten people in the audience, slumped on the picnic tables, and ten people on stage, locked into those chords. E-D-A. E-D-A.

As the day progressed more musicians showed—some returning from last night, others for the first time. Sometimes I was playing with total strangers, other times with people I had known for years. Singer-songwriter Jimmy LaFave got up and sang. Joe “King” Carrasco did too, bringing his dog with him. A guy got up and sang the chorus backward: “A-I-R-O-L-G, Airolg!” (“I’m from Wisconsin,” he explained.) Drummer Garrett Williams brought his young son up and each played a drum kit. Somebody read some Yeats, somebody else some Flann O’Brien. Singer-songwriter Beaver Nelson read from a pamphlet on irritable bowel syndrome. The guy from India woke up, stumbled onstage, and began to take a leak behind the drum riser. John Ratliff, who was playing the piano, asked him what he was doing. “Looking for my tools,” he replied.

The highlight came that afternoon, when Van Morrison himself joined in. I had contacted his management a few weeks before, letting them know we were doing this, but I also asked if Van wanted to participate somehow. His manager told me that Van hated the song and didn’t do it anymore, but he was playing a festival in Chester, England, and maybe we could work something out. I gave him the club’s phone number; he said if Morrison chose to do or say something, it would be between 3 p.m. and 4 p.m., Texas time. I talked with Rich Malley, a drummer and techie, who borrowed a homemade gizmo from a guy he worked with that would transfer a phone signal to an audio one that could then be played over the PA system. The gizmo looked like something from Plan 9 From Outer Space and Rich plugged it into the soundboard.

At 3:45 p.m. we were playing away, exhausted but aware that something cool could happen at any minute. All of a sudden I saw Rich running out of the Lunch’s office holding the club’s portable phone over his head. He connected it to the gizmo and we all quieted down. We could hear something through our stage monitors, guitars but no drums, coming from five thousand miles away, where the road manager was crouching onstage, holding a cell phone to another stage monitor. It was E-D-A all right, though Morrison was doing it a lot faster than we were. We sped up to his tempo, all of us aware that we were performing one of the great rock and roll songs of all time with the guy who wrote it. We heard him talking, introducing the song by saying that a bunch of people in Texas were playing “Gloria” for 24 hours. We heard the roar of the crowd. Then he began, “Like to tell ya ’bout my baby . . .” Onstage, we all looked at each other, grinning. He got to the chorus and we deliriously sang along.

After about two minutes of this, though, all of us in Austin started to get the same feeling, that we were losing our momentum, losing our song. We looked at each other, now with a different kind of knowledge: It was time to go back to the way we had been doing the song for seventeen hours. Tex Edwards took charge, yelling “G-L-O-R-I-A” and we all came in: “Gloria!” We drowned out Morrison and went back to doing the song our way.

The last few hours were a glorious mess, the stage packed—four people playing two drum kits, four guitarists, a piano player, an organ player, a trumpet player, a half-dozen people banging on cowbells and tambourines and singing. The last hour got louder and more frantic, and there was now finally a huge crowd for our huge energies—we were basically the opening act for the Saturday night lineup of Doctors’ Mob, David Garza, and Joe Ely. We held back the last chorus as long as possible, finally hitting it a few minutes before 9 p.m., crossing the 24-hour mark screaming “Gloria!” into the night.

For years friends and strangers have come up to me and gushed about playing the Gloriathon. I think back. Really? Were we onstage together? Have we all been swallowed up by the communal memory? The song ate us up that night, the memory might as well have, too. I have no idea how many of us played. It could have been fifty, it could have been one hundred. I like the haziness of that—it’s very, uh, Austin.

Ten years later, the site is part of the booming Second Street District. The square Silicon Laboratories structure that was built on the Lunch site is as much a part of the city skyline as any other modern building. Next door, in the space that held that general store 150 years ago, is upscale restaurant Lambert’s; across the street is the Minx boutique and BoConcept design consulting company; down the block the W Hotel is under construction. It is a very different world from 1999, and that’s fine. I’m not bitter. Cities evolve, and so do people. Hell, my latest band, the Savage Trip, played at Lambert’s during South by Southwest in March. We played a completely normal forty-minute set.

But sometimes, when I drive north across the South First Street bridge, I look at the landscape and remember those chords echoing off the long-gone buildings, and I try to remember what it felt like driving back to Liberty Lunch that morning.

This story has been updated to correct the opening lyrics of “Gloria” and to credit photographer Kevin Virobik-Adams.

- More About:

- Music