For the longest time, people believed that Godwin Park was one of the safest places in Houston. It nestles quietly in Meyerland, the heart of the city’s Jewish community, a neat square that is, in total, about the size of a city block. A cheery elementary school—named to the state’s honor roll, a banner notes—occupies one side of the park, but plenty of space remains for a soccer field, a baseball diamond, and a covered basketball court. The grass is shorn and green, the playground equipment freshly painted and sturdy. The park is shaded by benevolent oaks that are about the same age as the homes that surround it: cozy ranch houses from the fifties and sixties in Tudor, colonial, and contemporary variations, comfortable but never showy, with gardens lovingly tended. The people who congregate here on weekends—boys on bikes, new moms pushing strollers, elderly couples walking with clasped hands—are the type of folks you would want to be with: kind, contented, seemingly immune from life’s cruelties.

So maybe it was natural that sixteen-year-old Jonathan Finkelman felt safe enough to meet some strangers here late one night last December, just two days after Christmas. A strapping, good-looking Bellaire High School junior with bright eyes, a broad smile, and a casual sweetness, he knew this neighborhood as well as he knew the layout of his own home. Jonathan, the third-oldest of five brothers, had grown up here, as had his father and mother. Within the Jewish community, his grandfather was known for his philanthropy. Close friends were always nearby, as was the conservative synagogue, Beth Yeshurun, where Jonathan’s family worshipped. The Finkelmans had both money and respect, and for Jonathan, then, everything seemed all good—too good, perhaps, because up to this point, he had enjoyed the kind of cosseted life that sometimes stirs teenagers to take risks. This particular night was one of those times: Jonathan had come to Godwin Park to do a drug deal.

He was there to sell two bottles (some two hundred pills in all) of hydrocodone, an opium-based painkiller marketed as Lorcet, for $500, a hefty sum even for a kid from a wealthy family. That drugs were plentiful in a neighborhood as prosperous and placid as Meyerland, and in a school as prestigious as Bellaire—arguably the city’s best public school—would surprise no one. Drugs were everywhere, as socially segmented and niche marketed—bars (Xanax) for the rich kids, weed for the gang bangers, meth for the goths—as the designer sneakers and expensive handbags the students coveted.

A more cautious kid might have avoided this deal and stayed at home that night, watching TV. A more cautious kid might have been suspicious of the boy who law enforcement sources say set up the sale, a reedy, redheaded stoner of fifteen named Warren Payne. Maybe $500 was just too much to pass up, or maybe Jonathan’s trusting nature blinded him to the danger in the familiar. Warren and his sister went to Bellaire, just like he did. They lived in a big house not far from the one Jonathan shared with his father and stepmother. And Warren had bought this kind of painkiller from Jonathan before. That Warren had a Web site featuring gangsta music with violent lyrics, an album cover with a hooded black man pointing a Glock at the viewer, and a description of his occupation as “hustlin” was not exactly a warning sign in this day and age. Maybe Warren was just another kid out for a good time. But Jonathan must have felt that something about the deal wasn’t right, because he took the precaution of bringing along a friend from school, a wealthy party boy who described his interests online as “hott bitches and paintball.”

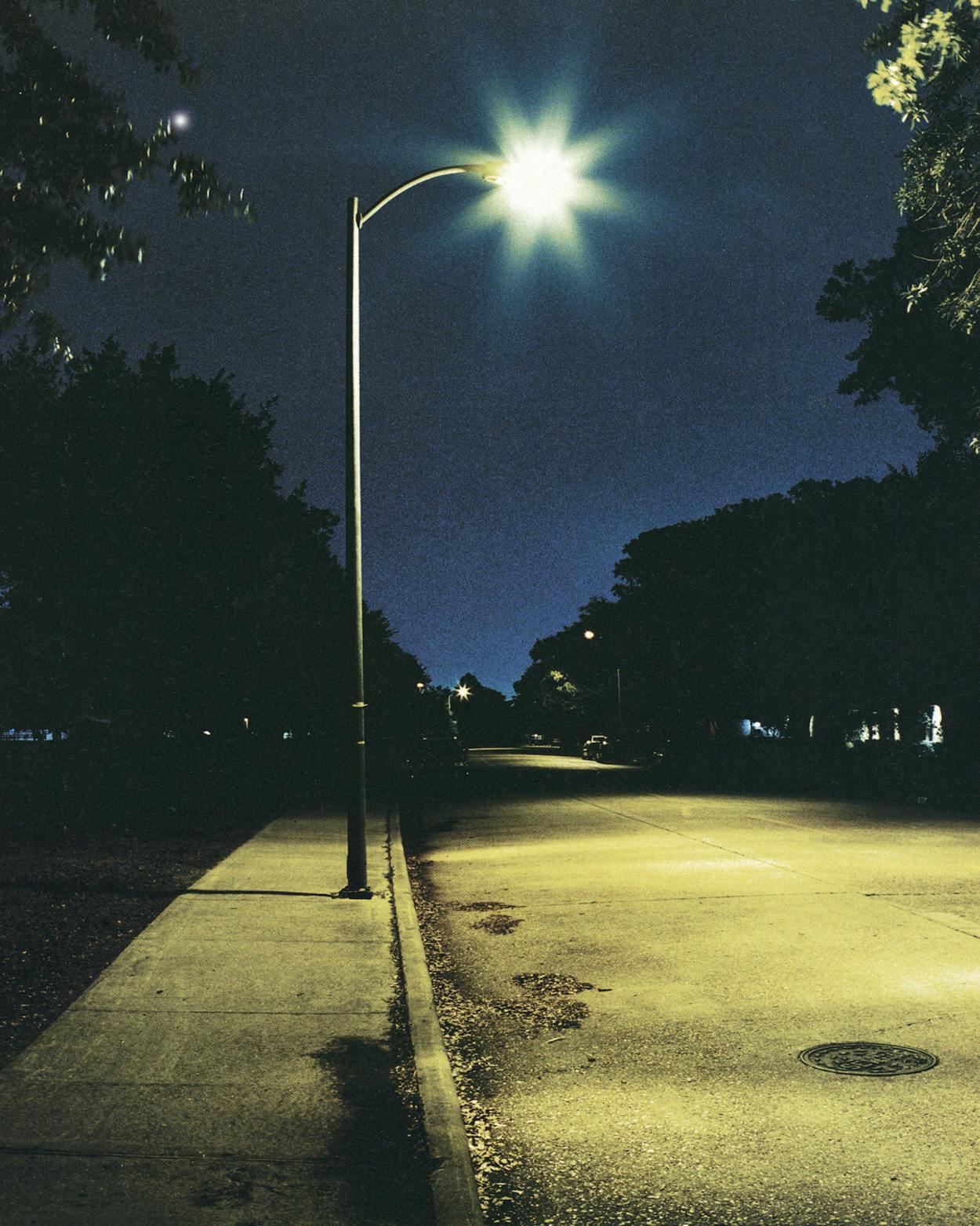

And so, just after eleven o’clock, Jonathan drove to the park in his seven-year-old Mitsubishi Diamante, pulled up on the wrong side of the road by the baseball diamond, and waited. Streetlights glowed dimly along the perimeter, but most of the people living around the park had shut off their porch lights, contributing to the darkness. The day had been unseasonably warm, so the night was cool but not winter cold, with just a hint of clingy Houston dampness.

Perhaps he should have noticed that Warren’s small posse of pals had gathered in the bleachers behind the diamond, restless, like an audience waiting for a play to begin. They were mostly fifteen or sixteen years old, white boys with long, unruly hair and troubled histories (including, in some instances, juvenile records), who pulled showily on their cigarettes. Every once in a while, a laugh cut through the night air.

Later, no one could remember when, exactly, the sedan arrived, driven by a black male, who remains unidentified except for a street name. Also in the car were a heavy, moonfaced Hispanic man, whose younger brother, a friend of Warren’s, was watching from the bleachers, and another black male, an eighteen-year-old high school dropout named Dontae Terrell Moore. Dontae, who had skin the color of rich, black coffee and pensive, thoughtful eyes, lived just a few miles from Meyerland but a world away from its comforts. In the Hiram Clarke neighborhood, the ranch houses were much smaller, the windows had bars, and weeds choked the front yards. Since quitting school the previous spring, Dontae had spent most of his days playing video games with friends and minding all the little kids crowding his aunt’s house on Woodring Drive, where he lived.

The meeting, then, had the feel of a summit between two very different but interdependent nations, with drugs and drug money as the common bond. Maybe if you lived in Hiram Clarke instead of Meyerland, you used the cash to pay the rent or the electric bill instead of buying an iPod, but maybe not. All kids want nice things, no matter what side of town they live on, and nowadays everyone wants them in a hurry.

One of the black men—the police say it was Dontae—got out of the sedan and into Jonathan’s Mitsubishi, but not before seeing that Warren had gotten in too. Jonathan may have sensed the pivotal nature of that moment—that his life was about to go tragically, irrevocably awry—but if so, he knew that it was too late to heed that inner warning. The air inside the car was close, thick with possibility. It was something straight out of Requiem for a Dream, a drug movie that was Warren’s favorite.

Only this was real life. The sound of a gunshot shattered the stillness of Godwin Park and sent the boys in the bleachers scattering like panicked pigeons. There was panic in the car too. “Oh, my God! Oh, my God!” Warren screamed as more shots were fired. He managed to shove open the car door and stumble out onto the grass before a bullet caught him in the abdomen. He staggered forward another ninety feet before collapsing. “I’m hit! I’m hit!” he screamed, writhing on the ground while he looked frantically about for anyone who could help. One of Warren’s friends rushed toward him and threw himself over his body, shielding him from further danger. Before the sedan squealed off with its passengers, one last shot took out a tire on the Mitsubishi, just to make sure it wasn’t going anywhere.

It wasn’t, but for a different reason. In the front seat of his car, Jonathan Finkelman lay dying from a gunshot wound that had destroyed the left side of his head. His wallet was missing, and there was blood everywhere, even on the two bottles of pills on the seat beneath him.

The whole thing was over in less than a minute. That was about how long it took to ruin several lives that night, along with the illusion of safety for the people who switched on their porch lights and came upon the carnage in Godwin Park.

Talk to any number of psychologists today who deal with teenagers, and they will tell you that many of the kids they see are not in touch with reality. Parents with a clear memory of their own adolescent years will not regard this piece of information as news. Teenagers have never been in touch with the real world; their job is to rebel against it and forge their own identities, which will allow them to function in the world they will inherit and, one hopes, improve. But when mental health professionals describe being out of touch with reality today, they are talking about something else: a blurring of the real and the unreal, aided and abetted by technology.

If you are the parent of a teenager, as I am, you know what I’m talking about. The sound of a constantly ringing family phone is no more; it has been replaced by the clicking of the computer keyboard or the beep of a cell phone announcing the arrival of a text message. Teenagers have their own virtual universes, which are free from adult supervision at a time when threats to their health and well-being have never been greater. The list of factors to blame is long and obvious: easy access to drugs (many of which Mom and Dad are taking legally), easy access to alcohol (ditto), easy access to sex (either in real life or through cable TV or Web porn), as well as more-familiar pressures such as divorce, rampant materialism, and absurd academic demands. But there is one development that is unique to this generation of teenagers, and that is the omnipresent glorification of violence. Kids are bombarded with it—on television, at the movies, in video games, in music, and on the Internet. Street culture has married technology, and the result is a nightmare for parents and a siren song for kids. The difficulties of being a teenager haven’t changed, but society has, leaving those kids prone to risk taking drawn to ever more dangerous activities. To make matters worse, everything happens at breakneck speed, making rational thought and reflection nearly impossible. (It’s notable that among rich kids under intense academic pressure, the drugs of choice are ecstasy, weed, and prescription painkillers—substances that soften the world and slow it down.)

The easiest way to observe this shift is by logging on to MySpace.com. The Web site was created in 1998 as a place for musicians to promote their bands. (It was acquired last year for $580 million by conservative billionaire Rupert Murdoch, which will be ironic only until it starts making money.) MySpace quickly caught on with teenagers, who began designing their own Web pages with their own photographs, favorite music, personality quizzes, and messages from friends. To protect against Web predators, kids can set up private sites where only people they know can visit (a concept that parents can trust only at their peril).

It is salient and glaringly metaphoric that the way one makes a MySpace page is by creating a Web identity—the kind of psychological shape-shifting that teenagers do so naturally, as they change their minds about who they are. So, appropriately, there are kids on MySpace who worry about eating meat, the Iraq war, and global warming, as well as football, baseball, soccer, their golden retrievers, and what they are going to do this weekend. But a sampling of Web pages of kids who go to Bellaire reveals something darker, and it’s certainly not exclusive to that school—an affinity for extreme profanity and degradation of all sorts. Fourteen- and fifteen-year-old girls strike poses they must have learned on MTV, often in bikinis or underwear, with T-shirts that say “I’m a hustla.” The boys use screen names like “PimpiN At Its FinesT” or “Bitch . . . Moneys All I Think Of.” On one questionnaire, a student states as the goal he would like to achieve this year, “bone a mom.” A great many kids list their income as $250,000 a year, though whether this is what their parents make or what they assume they will make one day is anyone’s guess. The patois would give Bill Cosby a coronary: “I always got luv for ya fly ass white boy u ma nigga fa real” one girl wrote to her boyfriend. Drugs are bought and sold as casually and guiltlessly as if they were candy. Q:“do u still want those GG the yellow ones?” A:“yeh I do want them if u got I want em tomorrow.” Though the kids often sound very affectionate, that love is laced with a sharp slap of brutality and anger: “haha i love u 2 babicutass . . . hottgirl,” for instance. If all this is just virtual posturing, as some therapists suggested to me, the rebellious anger behind it seems very real.

Some of the angriest kids were those in Godwin Park that night, most notably Warren Payne and his friend Steven Lopez. The two had been pals since middle school, and it was Steve who would shield Warren’s wounded body in Godwin Park. Warren’s father was a successful patent attorney, and they lived in a McMansion not far from Bellaire High. Steve’s father was a handyman for an apartment complex in nearby Linkwood. Steve shared a cramped apartment with his parents, his sister, her lover, their baby, and, occasionally, his older brother Jeffrey. But the differences in the boys’ backgrounds didn’t matter. What they had in common was a passion for the gangsta life embodied by the hip-hop music they loved. Even though Steve was a teddy-bearish, baby-faced fifteen-year-old who struggled with school in the real world, the photo he posted of himself on his MySpace page showed him smoking a blunt under a profane caption. He featured pictures of murdered rapper Tupac Shakur, Al Pacino in Scarface, and Robert De Niro in Goodfellas.

On Warren’s site, in addition to the hooded man with the Glock, he put up photos of himself shooting the bird, photos of cough syrup bottles and marijuana, and photos of condoms. He listed his hometown as “Screwston.” Both boys liked to refer to their friends, black and white, as “niggas.” As different as they were, the common denominator of their lives was music and the violent anger it expressed. If that anger had more basis in Steve’s circumstances—cramped quarters, no money, an obstructed view of the future—than Warren’s, it nevertheless reinforced in Warren a nihilism that had as its source upper-middle-class ennui.

While the majority of teens will, as always, graduate from high school in one piece and go on to become responsible citizens, those who are vulnerable economically and psychologically are finding it much harder to avoid the proverbial bad choices, coming of age on their own, with too few role models to bring balance to their lives. This fact was brought home to me during an interview with a Bellaire sophomore who suggested, without irony, that making drug deals had helped her to grow up. “When you do drugs, you learn to watch your back,” she told me. “It teaches you how to treat people. When you are around drug dealers, you can’t act stupid. You have to be cool and collected. You learn to sit there and keep to yourself; you learn to say the right things to the right people. I used to be a lot more outgoing. Now I’m more calm and collected.”

Hence, reality and virtuality become the same. Or, as Phillip Guerrero, the homicide investigator in charge of the Finkelman case, told me, “The kids I’ve talked to don’t appreciate the value of life. They think it’s a big game.” The nature of teenage rebellion today—just like that of their parents in years past—reflects the essence of the culture, distilled to a discouraging purity, and the death of Jonathan Finkelman becomes a parable for how easily the bad in American life now drives out the good. Sometimes it happens gradually, almost invisibly, and sometimes it happens swiftly, with the squeeze of a trigger on a dark winter night.

When Jonathan’s friends remember him, they bestow upon him the ultimate high school accolade: He always said hi. Moving through the halls of Bellaire with an eager, big guy’s gait—head down, shoulders a little hunched, smile omnipresent—he was never too busy to throw his arms around a friend. “Even the black girls, which a lot of the white boys will not do,” one remarked. At socially stratified Bellaire, this was no small thing. For many decades after its founding, in 1955, the school was all white and earned the nickname Hebrew High because of its hardworking, ambitious Jewish students, zoned to attend Bellaire from their homes in Meyerland. Today, Bellaire still looks like the only high school in a small town: The architecture is blocky and unexceptional, numerous parks and playgrounds are located nearby, and the local city hall, police station, and water tower (with “Bellaire” written across it, in a gay, cursive swoop) are just a block or two away. The neighborhood carries the same name and is, in fact, an incorporated city surrounded by Houston. Bellaire High, however, draws students not only from Bellaire but also from nearby Houston neighborhoods.

It is inside the school that the changes in Bellaire are most obvious. One is diversity; in the halls you see whites, blacks, Hispanics, and East and Central Asians. Another is class: Bellaire is divided by income level in a way it never was before. In the mid- to late eighties, as Houston began to recover from the oil bust, families were drawn to the large oak-and-pine-shaded lots of Bellaire and adjacent Meyerland, where they could tear down modest ranch homes and build mini-mansions. (In 1986 the average cost of a house in Bellaire was $75,000; it is now $500,000.) Even better, they could send their kids to great public schools. If crime rose slightly—a series of violent burglaries swept through the area in 1987—it didn’t really matter. Residents could by then afford to pool their cash and hire private patrols, sending the crime rate back down. Sometimes, too, the rent-a-cops were a lot more lenient than the real thing. “I live in Meyerland” was a common refrain among kids who were caught speeding or with contraband, in hopes they’d get off light.

Meanwhile, the demographics of the nearby apartment complexes that were part of the Bellaire attendance zone were changing too. Built for boom-era white singles, who fled once the economy cratered, the complexes soon became home to struggling immigrants eager to move into better housing and send their kids to good schools and to black families trying to get away from the old inner-city wards. To keep whites from leaving, the high school added International Baccalaureate programs to its Advanced Placement offerings, and as the surrounding neighborhoods changed, more and more affluent Bellaire parents pushed to get their kids into these classes. But these outstanding academic programs created, over time, a school within a school, in which the smartest kids with the most advantages took the IB and AP tracks, while everyone else was relegated to classes that, for various reasons—discipline problems, less talented teachers, lower standards—just weren’t as good.

These changes in the socioeconomic balance of the school have shown up in its once-glorious statistics. Bellaire still belongs among the top high schools in the nation; in Newsweek’s 2005 poll of the best American high schools, it ranked 112, and its 3,400 students produced a raft of AP scholars (323). This year, Bellaire has 40 National Merit Scholars. Seniors are heading, as always, for Harvard, MIT, Princeton, Stanford, Yale, Columbia, and other top schools. Orchestra, debate, science, and baseball programs continue to win national and international honors. The case could be made that the school has triumphed despite being under enormous social pressures. But success has not come without pain. In-school suspensions jumped from 336 in the 1999–2000 school year to 855 in 2003–2004, the last year for which statistics are available. The total number of disciplinary actions soared from 441 to 1,082 in the same period. Then things got worse: In the months between the Christmas season of 2005, when Jonathan Finkelman was murdered, and the end of February 2006, a popular football star, Desmond Hamilton, was shot and killed; a sophomore girl was charged with shooting and killing her mother; and a student was stabbed more than twenty times, leaving a pool of blood in the hallway for other kids to step over. “This year it seems like the place has gone to hell” was the way one sophomore described the situation at Bellaire to me. Today, it isn’t unusual to stroll down the halls and hear kids from all programs—from IB and AP to special ed—addressing one another as “pimps” and “hos.”

Jonathan had the ability and the desire to inhabit all worlds. As a freshman, he was as well liked by the jocks on the football team as he was beloved by his old friends from Camp Young Judea, where he had chosen to hold his bar mitzvah. The black and Hispanic kids envied his myriad Ecko T-shirts, which are manufactured by the company his family bought a controlling interest in back in 1999 and marketed to kids all over the country. But most important to Jonathan was his family, which was so close as to be claustrophobic.

That the Finkelmans settled in the Meyerland vicinity was notable; the neighborhood was a place where Jews could take care of their own and, they believed, could protect their children from negative influences while teaching them to follow religious tradition and embrace the values of family, education, achievement, and community. Jonathan’s grandfather Wolf Finkelman arrived there in 1946, having lost his parents, three sisters, and three brothers in concentration camps. Relocated with the help of Jewish family services, he finished high school, married, and eventually built a very successful import business, which he recently turned over to two of his three sons, Alan (Jonathan’s father) and Steve. Within Houston’s Jewish community, the Finkelmans were admired for their generosity and their intense loyalty to one another.

Jonathan’s parents divorced when he was seven, however, and Alan remarried soon after. Alan was strong willed and opinionated, as were Jonathan’s older brothers, David and Joshua. Indulged and praised at every turn, the older boys fell out of favor with Bellaire parents as they grew up and developed a reputation as troublemakers. According to law enforcement sources, a few parents went so far as to ask Alan to try to control his older sons, but nothing changed. “The boys were raised with unconditional love,” recalled a parent whose children grew up in Bellaire. “It was ‘circle the wagons,’ because they were right and everyone else was wrong.”

Both boys had encounters with the law that involved drugs, and both received deferred adjudication. Alan intervened to protect his sons when he could: When Joshua was sentenced to fifteen days in the county jail on a drug charge in 2004, for instance, his father asked the court for leniency. “He has changed the majority of his past acquaintances,” Alan wrote the judge. “On many occasions I have heard Joshua say to someone that he is unable to play football or attend an out-of-state university because ‘I screwed up.’ ” His request was turned down.

Alan’s behavior was in tune with that of many prosperous parents who are desperate to save their children from all threats large and small. The young men in Godwin Park were described by friends and family as “good boys,” regardless of their involvement with drugs and crime and violence. “I see denial every day,” the principal of a Houston alternative high school told me. “Parents don’t want to see what’s out there.”

For Jonathan, strong family ties were both a blessing and a curse. He idolized his older brothers, but their reputations preceded him at Bellaire. Though he was more like his mother—quieter, gentler—the kids and the teachers looked for a wild streak, and he felt compelled to fulfill their expectations. The trouble was, Jonathan wasn’t particularly tough. He didn’t really enjoy playing football, and in an extraordinary school he was an ordinary student. He needed an identity to keep himself afloat in the social sea of affluent Bellaire, where, one of his old friends told me, “Everybody knows every brand. They do expensive. That’s what makes you at Bellaire: your car, your clothes. You won’t see the same outfit twice.” Jonathan retained his camp friends—the good kids who, like him, raised money for Ukrainian orphans—but he also found a place among the school’s faster, richer students, the ones who had been in rehab, who were familiar with Mexican beach resorts, and who touted Lacoste shirts on their MySpace pages as if they were bespoke. Jonathan had the money to join in: He took friends to the World Series and to expensive restaurants. Selling drugs, casually, just to people he knew, kept money in his pockets and made him even more popular. And Jonathan had backup: “Nobody messed with him because they were afraid of his brothers,” said the same friend. “If he had a problem, his brothers would take care of it.”

He spent a portion of one summer at Houston Learning Academy, an alternative school, trying to beef up his academics alongside other kids who were trying to improve their grades and test scores, and he spent a year at a yeshiva in New Jersey, trying again to figure out who he was. “He never really said no,” a close friend of his, a pretty girl still struggling with his death, remarked. “He didn’t have a problem with people telling him what to do, and he’d do it.”

To Rice University sociology professor Stephen Klineberg, the changes occurring in west Houston, in and around Bellaire, where Jonathan Finkelman grew up, and the encroaching poorer sectors like Hiram Clarke, around six miles away, where Dontae Moore grew up, reflect “a double revolution that is taking place nationwide.” In places like Meyerland, the rich continue to get richer—“the class structure is increasingly rigidified,” in Klineberg’s jargon—while in places like Hiram Clarke, poorer minorities, moving into neighborhoods vacated by middle-class whites, have the proximity to witness but not share in the bounty of those who have done very well. On the one hand, this generation of kids is more comfortable with diversity than any other in the history of the United States. But at the same time, class divisions widened by poor schools and limited opportunity threaten that harmony. Immigrant parents might be proud that they are doing better than relatives back in the home country, but their children compare themselves with American kids and find their lives wanting. Some kids work hard to pull themselves up, but it takes a very strong child—with supportive, attentive, driven parents (something in short supply these days, even on the right side of the tracks)—to succeed in this environment, which often requires long bus rides to and from school, working at minimum-wage jobs afterward, and finishing homework after that.

Throughout his early years, Dontae Moore kept himself afloat on a child’s natural optimism. The Hiram Clarke neighborhood did not automatically encourage looking on the bright side. It had once been settled by middle-class whites, many of whom worked in the growing Medical Center area. Nearby Windsor Village Methodist Church, which is now among the largest black churches in the nation, was populated almost entirely by whites as recently as the late seventies. The Houston Independent School District bused white kids to a predominantly black high school to try to maintain racial balance, but to no avail. The whites left, and blacks moved from decaying inner-city neighborhoods like the Fifth Ward to these once-suburban homes. So too did Hispanic immigrants, who could save enough money by sharing cramped apartments to eventually move up to freestanding houses. Over time, the median household income of the neighborhood declined to its current $36,000 a year, with 17 percent of families below the poverty level. For young black men, the unemployment rate is a disaster: Only 20 percent of black male teens are employed today, versus 52 percent in 1954. Hiram Clarke is not a place to dawdle; 76 percent of the deaths in the neighborhood have been linked to destructive habits, which can include alcohol and drug addiction and abuse of various kinds.

Dontae’s family was part of this diaspora. After living in several crumbling black neighborhoods around the city, an aunt named Joyce Hill landed here in 1995, settling in a worn, four-bedroom, 1,300-square-foot house, taking in any family members who needed her help, a group that already included the solemn, dark-skinned son of her brother.

In his room at Aunt Joyce’s house, Dontae stored the keepsakes of a difficult life: an album with a faded photo of his mother, beaming and beautiful in her Sunday best, and a picture of the grandmother who took care of him after drugs took his mom away and she gave up her children, including Dontae, who was then three years old. (That grandmother died in front of Dontae, collapsing in the driveway of their home one day, leading to his life with his father’s sister.) There are pictures of brothers and sisters, who are today scattered around the city, and of his father, who on summer weekends took Dontae and his younger brothers fishing in Clear Lake or Galveston. “It was like a man meeting,” Dontae told me during one of our two interviews at the Harris County jail. There is also an old report card tucked into the album, from Windsor Village Elementary in 1996, when he was in the third grade; with an overall average of 71, Dontae must have been proud of the 80 he got in spelling.

He was a good boy for whom bad luck had a serious attraction. When Dontae was in the ninth grade, his dreams of playing high school football abruptly ended when he was struck by a car while crossing the street after getting off a Metro bus. He woke up in the middle of the street, one leg broken in five places. After doctors installed steel rods and a plate in the leg, he spent a year in bed, cut from the football team, watching TV, a cousin or two curled up next to him for company. “Once I got in the accident,” he said, “I felt like half my life was over.” He bounced in and out of a few more schools, got in a fight when provoked, but generally stayed out of trouble. At home he was the chief child tender, watching the ever-growing number of babies who came with the other relatives his aunt took in. At one point, at least four adults and eight kids lived in the rent house on Woodring. “I used to walk the kids to school and pick them up—make sure nothing ever happened to them, make sure nothing ever happened to my people,” Dontae explained.

“He looked at himself as the man of the house,” Aunt Joyce told me, and this was true in the extreme, in that he almost never left. Even his girlfriend, a pretty, studious eighteen-year-old who is now at Texas Southern University, knew better than to invite Dontae to her high school prom. For his whole life, until he was charged with capital murder for allegedly shooting Jonathan Finkelman, Dontae Terrell Moore never spent a night away from his family.

By fall 2005, the beginning of Jonathan’s junior year at Bellaire, both of his brothers had left for college. The pressure intensified to choose between kids from nice homes who occasionally used drugs and alcohol and kids from even nicer homes who habitually used drugs and alcohol. The girls he knew from camp and his friends from the football team urged him to slow down, to cut back on the hard partying and the marijuana, but he didn’t. That his behavior was self-destructive was not lost on him. “I like hanging out with you because you make me feel like a good person,” he told one of the many girls who wanted to be close with him. “I feel like there’s something missing in my life,” he told another. It didn’t help that he was not academically inclined. As a student who sometimes helped him with his work explained, “Bellaire is a very competitive school. I have a 3.0, and I’m in the third quarter of my class.” Jonathan wasn’t like the driven kids who pushed to get into the top 10 percent of their class; he just wanted to graduate, go to college, and join the family business so, he told friends, he could stay home with his kids.

A family cruise over the winter break seemed to provide the needed respite from all these pressures. Alan’s second wife had just had a baby, so it was only his father and his brothers, together in a way they hadn’t been for quite some time. The Caribbean cruise on the Grand Princess went to Belize, Cozumel, and Grand Cayman; the boys spent most of their time in the casino, slipping comfortably into old roles. When a steward on the ship tried to keep the underage Jonathan from gambling, his brothers were there to make sure he got in. A friend from Bellaire was also onboard, and the two spent time together taking pictures with her cell phone camera, which she would later post on MySpace.

But back home for the rest of winter break, Jonathan returned to business as usual, which meant dealing. According to law enforcement sources, a Bellaire freshman named Warren Payne was looking to buy some drugs, and he called Jonathan, who mentioned Lorcet, part of the panoply of prescription painkillers that had been growing in popularity over the past few years. (Enterprising Texas kids had realized they could drive to the border, cross into Mexico, and legally buy drugs that produced highs equal to or better than the illegal drugs they had to sneak around to buy in the U.S.) Jonathan told Warren the price would be $20 for nine pills. The two agreed to meet later in the afternoon for the pickup.

Jonathan didn’t really know Warren, but the fact that Jonathan had a class with his older sister must have given the younger boy a pass. Warren’s predilections, however, should not have been hard to miss. At fifteen, he was deeply invested in the gangsta life. If you didn’t know that he was white and redheaded and lived with his father and stepmother in a $462,000, 3,733-square-foot house in Bellaire—plus swimming pool—you might think he was another bad boy from the hood. His MySpace page was a virtual paean to drugs and sex: It included a quiz titled “What thug drink are you?” (Answer: “You love just gettin f—ed up for the hell of it . . . your not drinkin to score because ur the ultimate thug . . .”), a parody of a handicapped sign featuring a man in a wheelchair receiving oral sex, and a photo of a woman’s buttocks adorned with what appeared to be a deep red slap mark. His friends seemed to love it: Female classmates were always sending him messages with hearts and smiley faces, and boys wanted him to chill with them.

What happened next makes sense only in the context of the essential irrationality of teenage life: Police investigators say that Warren met Jonathan on the street to buy the drugs, and Jonathan objected to the denomination of the bills. After an argument, he gave Warren fewer pills than he wanted. Later in the day, the police say, Warren called Jonathan and said he was working on a deal for a large number of pills. Jonathan could make $500. Was he interested?

He was. According to law enforcement sources, Warren called Jonathan’s phone several times that day. “The only reason Jonathan went through with the deal,” one of his friends explained, “was because it was a ridiculous amount of money.”

“It was getting kinda complicated at the house” is the way Deonti Rice, one of Dontae’s friends who was living with the family, describes what he saw as a worsening economic crisis on Woodring Drive late last year. Joyce Hill, who had worked at a McDonald’s near Loop 610 for several years, had hurt her back on the job and was on medical leave. She had been living from paycheck to paycheck. Earlier, she had found Dontae a job there, and he had worked alongside her, packing fries and doling out Happy Meals, even though he remained in almost constant pain from the accident. While Aunt Joyce worked hard to make ends meet, some of the boys in the house felt duty bound to help out. Dontae, never the best student, had dropped out of school the previous spring, when he was a junior; he had been having trouble with his leg and was hoping to have more surgery. He and his best friend, a boy named Chris, looked for better-paying jobs but had no luck. “We filled out applications at hardware stores, fast-food joints,” Chris said. “It would take a long time to call back or people wouldn’t call back.” Deonti had a job as a men’s room attendant at a hip club called Toc but lost it. “A two-story house. The light bills had to get paid. Nobody had a real steady job, and it was coming down on us,” Deonti said. “You gotta pay the bills, the lights—you gotta step up. You can’t just sit back and let things fall apart.” Aunt Joyce knew the neighborhood; she warned the boys in her house that she didn’t want them doing anything illegal to help pay the bills. “I tried to keep them out of trouble, but you can only do what you can do,” she said.

It was around that time, however, that Jeff Lopez—the brother of Warren Payne’s friend Steve—started showing up at Woodring on a regular basis. “He seemed like a cool person,” Dontae told me. “That’s why I hung around with him.” Dontae had met him at a house in the neighborhood, a place where a guy did tattoos for money. White kids showed up there too, usually high; Dontae could tell they had money by the things they had and the cars they drove.

Jeff was doing all right too. He was a couple of years older than Dontae and was paying his way through TSU. “Jeff was always about money,” Deonti said. “He carried himself like a person with money.” He dressed well, and he had a gold grill flecked with red that he wore over his teeth. For a long time it had seemed that money hadn’t mattered to Dontae; he was happy to stay home and play NBA video games or hang out with his old friends. “I could not have money, he could not have money, and we could just laugh all day,” Chris told me. To get out of the house, they’d take the bus to Sharpstown mall, sometimes, or the flea market on Martin Luther King. Other boys in the house were more restless; they’d watch TV shows like MTV Cribs and want their own private piece of the good life. Crime probably seemed like a viable career track. “People won’t hire me,” one of Dontae’s friends told me while we were eating at a fast-food joint. “Are you gonna do it this way?” he asked, motioning toward the kids working behind the counter. “Or the fast way? If that’s the way I gotta do it, that’s the way I’m gonna do it.”

It was Jeff who gave Dontae a glimpse of the faster world, particularly as Jeff spent more and more nights away from his family and more time sleeping on the couch at Woodring. “Jeff was constantly throwing money in Dontae’s face” was the way one member of the household put it. On the other hand, Jeff paid his way, respected Aunt Joyce, and sometimes bought fast food for everyone in the house. The only problems were his constantly ringing cell phone and the comings and goings—short trips that, more and more often, took Dontae away from the house.

Then, one December night, Jeff asked Dontae to go out riding with him. He got into a sedan with Jeff and a black man whose name no one seems to know and headed for Godwin Park.

There is very little agreement about what really happened in Jonathan Finkelman’s car on the night of December 27. In the disjointed accounts police investigators gathered after the shooting, the only undisputed fact seems to be that a young black male got out of the sedan and into Jonathan’s car along with Warren Payne. Once inside, after some discussion, the black male pulled a gun and announced his intention to rob everyone present by saying, “Give me your stuff.” When Jonathan and the friend he had brought along were slow to react, he pointed the gun at Jonathan’s head to show that he was serious. Warren told police investigators that Jonathan reached for the gun. A struggle ensued, shots were fired inside the car, and one hit Jonathan in the head, showering the interior with blood.

The other three occupants stumbled out of the car at the same time, running either to escape more shots or to escape arrest. Warren tried to race across the grass, but the bullet that felled him had pierced his liver, passed through his lung, and narrowly missed his aorta before exiting his body. One of the boys called 911, as did several residents who lived around the park. Jonathan’s front seat passenger escaped into some nearby bushes and called one of Jonathan’s closest friends, who, in turn, called his father, a doctor, who rushed to the scene and gave Jonathan CPR, to no avail. Warren was taken away in an ambulance with life-threatening injuries.

The police who arrived at Godwin found their teenage witnesses uncooperative: No one seemed to know who had been in the park or who had fired the shots. In all the confusion of that night, one detail has stayed in the minds of a few people on the scene: Alan Finkelman and his brother Steve both arrived at the scene wearing Ecko T-shirts, one of the gangbangers’ favorite brands.

It didn’t take long for the police to track down Jeff Lopez. He was arrested on December 29, two days after the shooting, and charged with aggravated robbery with a deadly weapon. His indictment reads that “he did . . . intentionally and knowingly threaten and place Jonathan Finkelman in fear of bodily injury and death, and . . . did then and there use and exhibit a deadly weapon . . .” Witnesses told the police he’d had a shotgun. Interrogated, he claimed two Jamaicans had committed the crime at Godwin. Then he said it was two guys from New Orleans. After he was released on $53,000 bond, he stayed away from the Woodring house, though he would call, on occasion. “I’m not going down for capital murder,” he would say, chewing over his case with anyone who answered the phone. In the meantime, several of the boys, including Warren, had identified Dontae out of a photo lineup.

Just before Valentine’s Day, Jeff was arrested again, for possession with intent to deliver “a controlled substance, namely, 3, 4 methylenedioxy methamphetamine, weighing more than four grams and less than 400 grams.” This time there was no bond. He seems to have cooperated with the investigation: Almost a month later Dontae was arrested and charged with capital murder. (On his MySpace page, Steve Lopez posted a close-up of his brother sneering with his gold grill, and when friends asked about him, he answered, “Mayen he doin good mayne we just waittin to see wats good but hopefully everything goes well cuz people dont kno da real shit and dats y hes in there.”

Dontae now resides on the seventh floor of the Harris County jail. Unlike minor criminals, who sport orange jumpsuits, he is dressed in the yellow worn by all violent offenders, and the shackles on his arms and legs do not come off when he sees visitors. He says he did not shoot Jonathan, though he admits to being at the scene that night. “I am not supposed to be here,” he said of his current surroundings, and the story Jeff told investigators—presumably that Dontae was the gunman—is not, he says “the real story.” On his aunt’s advice, he reads the Bible often, most notably the Book of Job, and writes as best he can to the people he once took care of at home, begging the kids to make something of themselves: “I pray to Lord Jesus every other hour asking to forgive stupid mistakes I made in the past I just ask could I get cap murder drop to something else where I could get bond. Because only evidence is people lying on me . . . They say I’m Cold blooded killer every one know that’s not true.”

He is now an unwilling passenger on the Harris County capital murder train, which runs straight to death row, especially if you’re poor and black. The district attorney’s office can employ all the state’s resources to get the death penalty, while Dontae has only a court-appointed lawyer with far too many cases and far too little money to investigate his claims. The other attorneys his family saw expected retainers of at least $25,000. Dontae’s relatives want only a fair investigation and a fair trial. So far, the murder weapon, thought to have been a revolver, has not been found. Only one bullet was recovered from the crime scene. Dontae’s chief accuser has a criminal record, and the identification of Dontae (one of two black men on the scene) as the shooter by teenage boys on a dark night could probably be challenged by a good lawyer. Even the police say that the photograph from which Dontae was identified hardly resembles him. As Aunt Joyce’s eldest daughter, April, told me, “All the boys were doing something they had no business doing. Nobody’s gonna win. Everybody’s losing a child.”

Denial has set in on all fronts. Many of the kids now say that Jonathan was foolish to go to the park that night. “He got shot by sheer stupidity,” one e-mailed me. “Hanging out with the wrong people.” The Finkelman family, through a spokesman, insists that Jonathan’s murder was not a drug sale but a robbery gone wrong. Before he stopped talking to the press, Alan Finkelman contended that the Lorcet found in the car was legal. Critical of media accounts of his son’s death, he told the Houston Chronicle, “It was prescription drugs. This wasn’t like LSD or some funky-ass stuff. It was less money involved than you or I carry in our wallets.” Law enforcement sources, however, say Jonathan had no prescription for that particular drug.

Those loyal to Bellaire High and the Meyerland community retreated too. “Why don’t you do an article on a more-inner-city school?” a former student challenged me. “This is news?” a leader of the Jewish community asked. It was noteworthy that the person most vilified in the area following Jonathan’s death was not one of the kids involved in the killing but Peggy O’Hare, the Chronicle’s crime reporter, who wrote a poignant account of his life, titled “Teenage Tragedy.”

But the outcome hasn’t been tragic for everyone. Dontae and Jeff languish in jail, and Jonathan lies buried in a local Jewish cemetery—his grave marked for the first year, as Jewish tradition dictates, with stones from people who have visited it. But the person whose response to a dispute over drugs set in motion the events that led to Jonathan’s murder has not been charged with anything. Warren Payne, recovered from his injuries and out of drug rehab, has been spotted chatting on his cell phone in a park near Bellaire and smoking water pipes at the Hookah Bar, a teen hangout. His new photo on his MySpace page shows him in a hot and heavy clutch with his girlfriend, and his friends still post messages there. “Oh shit itz Warr3n!!!” one wrote recently. “Yo gangsta status cain’t B d3ni3d now U got a battl3 scar.”