This is part one of a two-part interview. Part two can be found here, and a condensed version of the entire interview can be found in the June issue of Texas Monthly. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

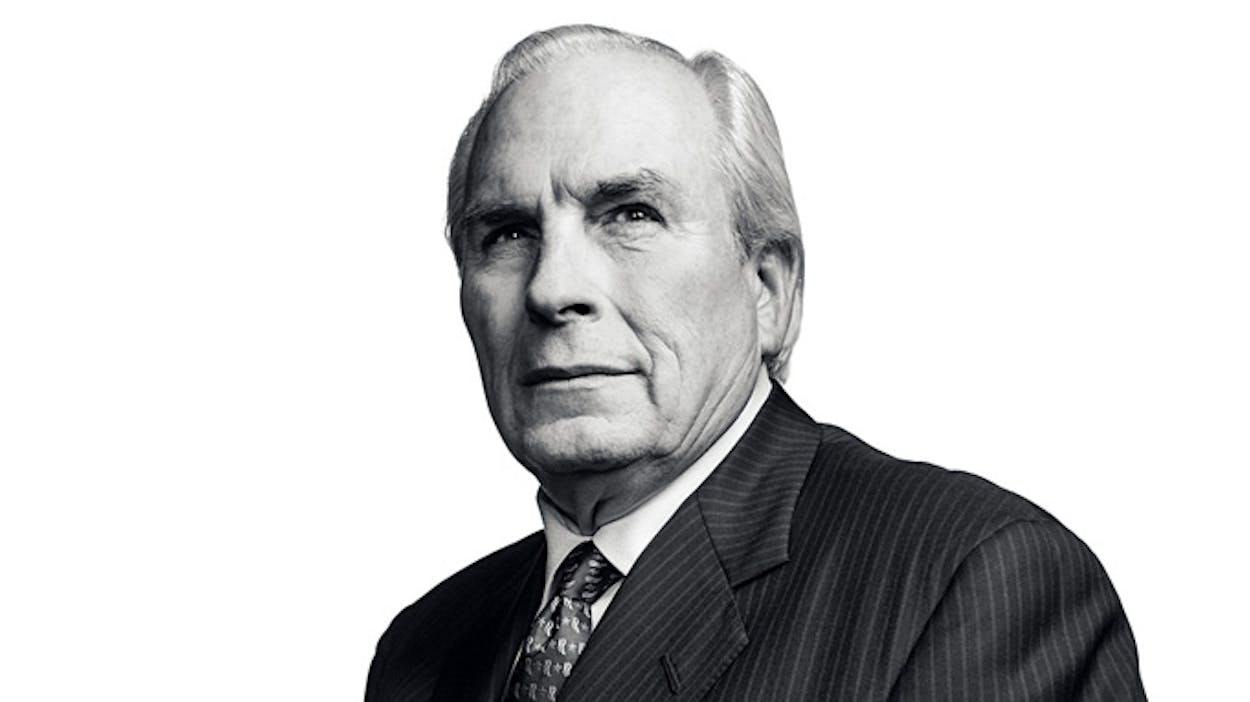

JAKE SILVERSTEIN: You became a regent in 2009, and you were elected chairman in 2011. At the time, what were your expectations of the job?

GENE POWELL: I knew that it was going to be a tremendous amount of work. Higher education in America is undergoing a transformation and is under a huge amount of pressure. And so I realized that we would be in the middle of that. I’m an entrepreneur. I’m used to very long hours, weekends, a lot of decision making. The board is full of entrepreneurs, hardworking people, and it moves at a very rapid pace. Long days and long nights. This is not the type of board you would have seen ten years ago.

JS: Which would have been more . . .

GP: More of a corporate board, more of a removed board, probably a slower working, more deliberative board. This is not a better board, it’s just a different board for different times. Primarily you have entrepreneurs—they’re smart, they work quick, they work hard, they don’t ponder a lot, they make good decisions, they make them quick. If they make a mistake on a decision, they go back and fix it. I don’t know if you know this: by law, we are to be the people’s representatives. We’re not to be academicians, we’re not to be administrators, but we’re to be the people’s representatives. So we’re here as the people’s representatives. What would the people in Texas have us do? What would they have us investigate? What would they ask questions about? What would they do about lowering costs? And you know, when I get outside of Austin and I travel the state, people tell me every day, “Thank you for what you’re doing. Now my Susie can take her courses online.” Or, “You’ve held costs down at Pan American and we really needed that last year because things were tough in South Texas.” And so the people outside the fog of war are extremely appreciative of what the board’s doing.

JS: So how do you rate the work that this group of regents has done in the last couple of years?

GP: In a word, outstanding. Outstanding. If you get past the fog of war, I would say to you that I do not believe that any system of higher education in America has accomplished what the UT System has in the past 24 months. We’ve got a new medical school for Austin and a new university in South Texas that will be the second-largest Hispanic-serving institution in America. We brought MyEdu, the student counseling software, to the system. We put up $105 million for a new engineering building at UT-Austin. We now have several $10,000 degrees across the system. I could go on for an hour.

JS: You mentioned the fog of war. There is a lot of outstanding work to point to, but these have also been some difficult years. Some intense conflicts have broken out between the board and UT-Austin, between the board and the Legislature. How would you characterize the nature of these conflicts? What are they about?

GP: I think the very first thing is, go back to my becoming chairman in February 2011. I came to the chairmanship along with three regents coming to the board [Alex Cranberg, Wallace Hall, and Brenda Pejovich]. At the time, we were not known to the public. UT-Austin alums and people who care deeply about UT-Austin became very concerned. So I would say the very first thing that happened was a great deal of fear from alumni, and the administration, and the staff. This fear created a group of assumptions that everybody started to hypothesize about. “Here are these new regents. What are they going to do?” When I mentioned blended online learning, the first response was, “Well, the chairman wants to turn us into the University of Phoenix or make us a diploma mill. He’s going to cheapen the university by wanting more enrollment or lower tuition. He wants to separate teaching from research. He doesn’t like research. The board doesn’t like research. They’re going to do away with all research dollars for the arts or the humanities.” These are just samples of what happened. So we had this fear, we had these assumptions. People then started to email their friends, and the Texas Exes got in on it, and before long the assumptions became almost set in concrete. And then an attack developed. People started to attack us because they were convinced that we had been sent here to do things. A lot of people believe we were sent to fire Bill Powers. A lot of people thought we were sent to fire Francisco Cigarroa. So you had all these attacks going on. And then the next year, in 2012, the attack got stepped up. It became a professional attack by a professional PR firm.

JS: Are you talking about the Coalition for the Advancement of Higher Education?

GP: Well, whoever. But I know that someone’s paying a professional PR firm between $200,000 and $300,000 a year to attack us. But I knew that making changes in the way we operate to face the new environment around higher education in America was going to be difficult. Change is always difficult.

JS: So would you agree with the characterization that this conflict is between folks who are trying to advance reforms and who are resistant to those reforms? Is that a useful frame?

GP: Well, I wouldn’t brand them as reforms. The reform movement in America is a very viable and big movement. But I don’t mark us down as part of the reform movement. What we are, I guess, is our own reform movement, and I think the individuals who are resistant to change are people who probably have not spent a lot of time studying higher education like we have. I’m not being derogatory, I’m just saying that people go about their daily lives and then hear some story about something the regents are considering, and they say, “Oh my gosh, that’s horrible! They’re gonna make us take all courses online!”

JS: Well, let me ask you about that. You mentioned earlier the attacks the board sustained in 2011 and 2012. You didn’t get to 2013 yet, but so far this year it’s been pretty much open season on regents.

GP: I think everybody went down early and got their hunting license.

JS: Recently we saw a video from three very prominent supporters, alumni of the university, a video that accuses Governor Rick Perry and some of the regents of being intent on tearing down the mandate on the state constitution to maintain UT as an institution of the first class. That’s more than a shot across the bow, that’s a shot—

GP: Right into the heart.

JS: How do you respond to an attack like that? These are not some nameless PR strategists. These are prominent alumni.

GP: Well, but let’s think about who they are. Most of the people that you see in attack mode are not Perry supporters. You have probably a couple of Democrats and someone who supported Kay Bailey Hutchison.

JS: Well, you did have Charles Tate, who was a supporter of Perry’s.

GP: Well, yeah, but not so much. I would say this: Notice that the video is all rumor, innuendo, and inference. There’s not a fact in it. They don’t accuse us of one factual thing. I would rather deal in facts. What I would say to them is, there’s not one shred of evidence that we want anything but a university of the first class, there’s not one shred of evidence that Governor Perry has ever wanted anything less than a university of the first class. We’ve had public votes, we’ve had public debates, we’ve had task force meetings. We’ve had committee meetings. Never, ever have we talked about making the University of Texas at Austin anything but a number one institution. This board has spent over $1 billion in the last two years on UT-Austin alone. We’ve spent it on a new medical school at $25 million a year committed. Now, former boards worked really hard to get that done for the last eight years. We were the ones that actually got it across the finish line. So there’s not one shred of evidence that that video is true. The facts show that this board of regents wants the University of Texas at Austin to not only be great—we want it to be the number one public institution in America. And we have put our money where our mouth is. $1 billion! I defy anyone to go across America and find an institution of higher learning that in the last two years has had a board lavish more good things on it than UT-Austin. And I defy anyone to go across America and find a system that has ever accomplished the things we’ve accomplished—ever, at any time in the history of higher education. I would never challenge the loyalty of these gentlemen, who I consider friends and great Texans, great supporters of UT. I just think they’re wrong in this instance. I think that the alleged death of the University of Texas at Austin is greatly overblown.

JS: You mentioned rumor and innuendo. The video strongly intimates that the conflicts between Governor Perry and UT are at some level the old Aggies versus Longhorns rivalry. I want to give you a chance, as someone who played football for Darrell Royal, to put that idea to rest.

GP: The governor, from what I’ve seen over the past ten years, has been one of the greatest advocates for higher education of any governor in any time in the state’s history. I have never heard him say one negative thing about the University of Texas. He wants both Texas A&M and the University of Texas to be the greatest schools in the nation. He has said to me, “There is absolutely no reason with as many resources as we have in this state, and as great of people as we have in this state, and as great of leadership as we have in this state, there is no reason that these two schools should not be ranked in the top ten and I want them there.” He said that to me personally. He has never given me any micromanagement. He’s never told me how to do things, who to hire, who to fire, how to run an organization. What he said to me was, “Gene, you know what needs to be done. I know you do. I know you care deeply about students. I know you care about higher education. Take the talents that you’ve been given, go there and do the work you know how to do.” And he has been a supporter. He has never, ever, ever said that he wants to tear down the University of Texas. He calls me occasionally on Sunday night and says, “How are you doing? How are you feeling? How’s Dana [Powell’s wife]? Put Dana on the phone. How are you doing, Dana? You guys are getting beat up over there.” And we laugh. I say, “Governor, I’m fine.” He said, “I just want you to know, Anita and I are thinking about you and praying for you. You’re doing a great job.” And that’s the extent of the conversation. If I run into him, he gives me a hug and says, “Hang in there.” I say, “What choice do I have?”

A couple of years ago, when I first became chairman, he had a meeting where the discussion was “How do we make Austin the next Silicon Valley?” The chancellor was there, the Chamber of Commerce was there, we had a number of researchers there. Two things were brought up that we had to do. One, we had to get a new engineering building at UT-Austin. Two, we had to have a medical school. The governor turned to me as we walked out and said, “How soon can you get that medical school and that engineering building?” Now that’s as close as a direct order as I’ve ever gotten from him. I said, “Governor, I’m working on the medical school right now. And I’m going to talk to President Powers about helping with the engineering building.” And we’ve done both. After the 2011 session, we said to President Powers, “We’ll up our contribution to $105 million and you match it with philanthropy and we’ll get the engineering building built.” We put the medical school on the front burner, we worked out the funding, got the regents to approve the funding, went to Senator [Kirk] Watson, got him to put the program together to get the election passed. Those two items came from Governor Perry.

JS: The medical school is a good example of a deal where the board and the Legislature worked very smoothly together. Now this session, the relations between the board and the Legislature have not gone as smoothly.

GP: Well, they were not smooth in 2011 either. It took me months to get rid of all the whelps.

JS: Yeah, well, it seems like it’s more than whelps this time around. You had the lieutenant governor getting somewhat emotional on the floor, talking about character assassination of President Powers. You had appropriations chair Jim Pitts talking about “witch hunts.” My question to you is, Why have relations broken down to this extent? And what can be done to kind of bring them back?

GP: Well, again, a lot of misinformation. It’s all part of this same campaign that we’re talking about.

JS: Right, but some of these legislators are people who you know very well.

GP: My friends.

JS: They could pick up the phone and talk to you. And yet still the misinformation is able to spread?

GP: The lieutenant governor is the perfect example. I spent two hours talking to him on the phone the day he made that comment. I said, “Governor, what you said today has no basis in fact. Whatsoever.” He said, “What do you mean?” I said, “Well, let me tell you about the things that you said. You talked about regents going on campuses and going to see deans and going around President Powers.”

JS: You’re referring to this accusation of micromanagement.

GP: Right, and I said, “That micromanaging has never happened.” He said, “How do you know that?” I said, “I’ll tell you how.” Under Texas law, Texas Education Code 65.31 says, “The board is authorized and directed—directed—to govern, operate, support, and maintain each of the component institutions that are now or may hereafter be included in a part of the University of Texas System.” The operative words being “directed.” We swore an oath to uphold this law. It didn’t say, “You may.” It said, “You shall.” And what did it say you shall do? “You shall govern.” It doesn’t say, “You shall make policy.” It says, “You shall govern.”

The point I’m making is that if we wanted to micromanage—or manage—the statute probably gives us a lot of leeway to do that. But we had a gentleman’s agreement when we passed the framework [“A Framework for Advancing Excellence,” which was drafted in 2011 by Chancellor Cigarroa]. We said, “Yes, we have the authority to do these things, but we are going to leave that in the hands of the chancellor.” And so if any regent wants to go see a president, a dean, a provost, a faculty member, here’s what we all agree to do: We call the chancellor’s office and either the executive vice chancellor of academic affairs or health affairs will make the appointment for the regent. They will then go with the regent to the appointment. The executive vice chancellor will call the provost and let the provost know that the regent is going to be on the campus and invite the provost to any meeting. When this allegation came out from Lieutenant Governor Dewhurst, I called the executive vice chancellor and I said, “I want you guys to tell me right now, here was the deal we had, has any regent gone on any campus outside of this protocol?” And the answer was, “Absolutely not.” I said, “Executive Vice Chancellor Reyes, have you been on every visit?” “Yessir.” “Has the provost always been called?” “Yessir.” “Have the regents been polite?” “Yessir.” “Have they micromanaged or even managed?” “Nosir.”

So I told Dewhurst this. He said, “Well, why would they tell me that?” So he backed up and said, “Here’s what happened to me.” He said, “I’m coming down the hall, and I see President Powers and he looks like heck. So I asked one of his staff members, “What’s wrong with President Powers?” And she said, “Oh, it’s terrible, it’s terrible. These regents are coming on campus, going around him, going to see his deans, going to see his faculty, and talking and giving them direction.” And she said, “Then they have these anonymous letters that were sent and I am sure that one of these regents wrote the anonymous letters, and they have salacious comments.” So Dewhurst got very upset, very emotional, and walked onto the floor, and these senators were speaking about President Powers and it was almost in funeral terms. He said, “I could see the black crepe paper hanging in the chamber.”

Now remember, I was the lieutenant governor’s statewide finance chair for his runoff election. He is a good friend. I said, “Lieutenant Governor, you have all my phone numbers. All you had to do was call me, take ten minute before you walked on the floor, and say, ‘Gene, is this true?’ You know I would have filled you in. I would have told you what the truth was.” And I said, “Now, let me tell you about these salacious comments. Regent Hall received two letters in the mail, anonymous letters. He called me and said, ’Chairman, what do I do with these?’ I said, ’Immediately scan them and send them to our general counsel, Francie Frederick. Then take your envelopes and your letters and mail them to her.’ He said, ‘Okay, I will do that.’ They come in to Francie Frederick. She looks at them and says, ’Okay, there’s some possible, actionable accusations here.’ We send them to compliance—this is all according to the set procedure we have. They go to compliance. The triage team of two or three individuals look at this, they tell President Powers since they’re about him. They say, ‘We’re going to investigate if two or three points in these letters are actionable, and we’re going to send you a copy of the letter.’ President Powers got the letter. He should not have shown it to anybody, but he did. She [Someone in President Powers’ office] says, ‘Well, I think Regent Hall probably wrote one of these letters.’”

This is what Dewhurst told me. He said, “And these letters say terrible things and now I think they’re passing them around.” I called Francie Frederick, and she said, “Absolutely not. Those letters have not gotten outside of our offices. Nobody has those letters, except President Powers’s office.” And so I said, “Lieutenant Governor, you just outed the letters and we’ve not put them out.” I said, “We’re now getting calls from the press, and we’re still not going to put them out.” And so that was a key moment and he was totally misled, totally misled.

JS: So what you took away from that moment was that a lot of the conflicts with the Legislature are based on them being misinformed.

GP: Absolutely. That was the week of my birthday, and I was on a little vacation and had just landed, and the phone rings and it’s someone saying, “Quick, turn on your computer, go to the Senate floor, Dewhurst is going off like a Roman candle.” And so I turned it on and watched, and then the rest of the afternoon I spent talking to the lieutenant governor and then the next day I visited with him again, I visited with his chief of staff and I said, “Governor, those things aren’t true. I’m just really, really sorry, but they’re not true.” And he apologized and said, “I’m very sorry.” But the damage was done. From there we get Chairman Pitts very upset over the law school foundation study, and that’s what he referred to as “witch hunt, witch hunt, witch hunt.” Senator [Judith] Zaffirini was very upset, and to some extent Senator [Kel] Seliger too. Speaker [Joe] Straus called me, and to his credit, he said, “Can you explain this to me?”

JS: What was he referring to?

GP: The things that Dewhurst said. So first I wrote him an email and gave him a list of the answers. And then I called and had an hour-long conversation with him. But you think about it, you know, we have a number of members who were upset, but we have 150 members of the House and 31 members of the Senate and I’m glad to talk to any of them. Any time they call me—and some of them call me and ask me—I’m glad to share the information with them, any information with them, because none of this stuff is true. The people who run the attacks, who run the campaigns, create hysteria. But I’m dealing in facts, and the facts are that these things are not happening, they have not happened, they won’t happen.

JS: I’d like to talk for a moment about the battles this session over records requests. The Legislature has requested documents from the board, the board has requested documents from UT-Austin. We seem to have gotten to a point now where everybody is getting what they want and what they need, but not without some struggle. You wrote a letter to the attorney general asking for some guidance on whether the board had to turn over everything that was being requested, and people interpreted that to mean the board had something to hide.

GP: Here’s what happened with that . . .

JS: And I’m certainly not suggesting that the board does have something to hide . . .

GP: No, and the board has nothing to hide. Let me state that up front. The board has nothing to hide. What happened was, I got a call from the system on a Thursday, and they said, “We’re having problems.” And I said, “Okay, explain the problems to me.” And they said, “We have the records request [from the Legislature] and we have some data to release. We have two or three regents who are very concerned about their personal attorneys, who they’ve asked to review things for them and now they’re being told that even their personal attorney’s information, their privileged information with their personal attorneys that maybe talked about the university, will have to be released to the Legislature. They have a hard time believing that they would have to give up their attorney-client privilege.” I said, “Well, you’re”—I was talking to some of the lawyers here, not the chief lawyer, but some of the other lawyers—“you’re the lawyer, do they [have to give up attorney-client privilege]?’” They said, “We don’t know.” This has never come up before. And I said, “Well, all right.” And they said, “We’re concerned that we don’t, we need to turn something over.” And I said, “Well, give me some legal options so I can straddle this line until I can get a resolution.”

It was said that I didn’t ever consult an attorney on this, but I had six attorneys telling me what I should do. I didn’t come up with this letter on my own. I asked them to give me a recommendation. They said, “If you do release this data, and you do breach the attorney-client privilege for these individuals, you can never put it back. It’s like toothpaste out of the tube. You just can’t put it back.” And that’s almost a constitutional right in this country, to have your own attorney. I have no idea as a layman whether or not the Legislature can breach that right. I don’t know. So they said, “Here’s the solution we would recommend: go to the attorney general and ask the attorney general that question, and ask about the release of this information.” So they did the letter, we sent it out on a Friday afternoon.

By eight o’clock that night, everything had gone wild: We were hiding things! The chairman was hiding things! But what I was trying to do was be abundantly cautious with people’s rights. I didn’t want to bridge the rights of the Legislature to have data, I also didn’t feel that it was my place to break the rights of the individual regents if they actually had them. Saturday afternoon, Jenny [LaCoste-Caputo, the executive director of public affairs for the UT System] called and said, “Patti Hart at the Houston Chronicle wants to know what you’re going to do next.” I said, “As soon as Francie lands tomorrow from her vacation in Bhutan, we will immediately start calling regents and scheduling a board meeting this week.”

That night, I wrote both Senator Watson and Senator Zaffirini, just because they’re friends, and said basically, “I want you to know I am working on a solution.” So we tell Patti Hart that I’m going to schedule a board meeting, but I can’t post it until Monday. On Sunday, Francie gets in from Bhutan, and we start working on an agenda, she starts calling regents, we start scheduling. Now remember, the letter went out at 4 p.m. on Friday. At 8:30 on Monday morning, we posted for a board meeting at 8:30 on Thursday, which was the earliest we could have had one. I couldn’t post with my general counsel gone out of town on a Friday, and so I’m trying to get something to the AG to say, “I don’t want to break the law, I want you to know I’m trying to do, so tell me, you know, I’m saying, tell me what I should do.” On Monday I came here, I went to see the AG, actually the deputy AG, Daniel Hodge, with Francie and we said, “Tell us about what you think about this attorney-client problem.” And we had a long discussion about it. I’ll keep it confidential, but he gave us good advice. We also talked to him about doing the investigation of the law school and could he do it and what it would be like and what the structure would be like.

And so then on Thursday morning we had a long executive session at which I reported to the board what the attorney general had told me about attorney-client privilege. By then, they’d also had time to talk to their attorneys and get their advice. So they had advice, and we had advice from the attorney general. We had two unanimous votes, released the data, and asked the AG to do the report. Five and a half days it took me, from Friday night to Thursday at eleven when we voted. I couldn’t have moved any faster. So again, anybody who’s predisposed to see something bad about what we’re doing or to impute to us some type of illegality, some nefarious reasoning or positioning, is going to see us in that light. But it did not happen. That’s not the way it happened.

JS: Both of those situations strike me as episodes where you’re dealing with a complicated problem that has a lot of constituents, and every decision plays out in an overheated environment. Then you get a little politics sprinkled in and . . .

GP: You’ve got the perfect storm. Each one of these has been the perfect storm. The temperature’s just right, the people are just at the boiling point, everybody’s sitting in position and they’re nervous and all of the sudden somebody drops a little salt in the pot and it boils over, and it’s a great—I’ve sworn off the metaphors, but that’s a great one.

JS: As long as they don’t involve automobiles.

GP: I knew it would come up.

JS: I’m not going to ask you about the Bel Air. So last question about all this: What can be done at this point to put this all to bed and move forward? What steps need to be taken by the board or by the legislature to move forward?

GP: Look, let’s stipulate that the Legislature is a great partner of the system, has been for many, many years. They set the University of Texas up in the 1880’s. They’re the ones that gave us the West Texas lands. They have been supporting us with appropriations for many, many years. They have provided many tuition revenue bonds for buildings to be built. The Legislature has been a great supporter of the system, so I have no negative things to say about the Legislature. They’re part of our government, they’re doing the things that they do. They have constituents that are very adamant, and I have no problem with them being adamant, they are emotionally engaged with the university and they’re making a lot of noise. The three regents have been making their rounds in the Capitol, which they’ve not done before. They’ve been going to see people to show them they don’t have horns.

JS: Is that an acknowledgment that maybe the board could have done better at reaching out to the legislature in the first place?

GP: Well, I think the new regents did not fully understand, and it’s hard to understand. I’ve spent fifteen years or so in the town every session working on various things. I’ve learned a lot from older, wiser heads than me about how it works in the big pink building. The new regents I don’t think really recognized the need to communicate with the members and I think they do recognize that now. I think Wallace [Hall] has been very open about that Alex [Cranberg] has been going by and seeing people. He’s befriended Dewhurst, he’s talking a lot to Seliger. I think that’s one thing that we can do. I’m talking to my friends over there. The Monday morning that I went to see the AG, I went by and saw Pitts. I had already written to Watson and to Zaffirini; I went by and saw Chairman Pitts. We had a really nice, quick visit, and I said, “Chairman, I know that you’re upset about what happened Friday. I’m working on this, we just posted two hours ago, give me a little time, I will resolve this this week. We will resolve it.”

JS: We started off by noting that there’s a debate under way between folks who are interested in trying to reform higher education and folks who maybe don’t trust those changes. I wonder if we could talk a little bit about some of those reforms themselves. The debate over higher ed reforms is sometimes framed as a conflict between elitism and populism. You have the university faculty and administration, who only care about the prestige of the university, the research, contributing to knowledge. And then you have the reformers who are more interested in expanding accessibility and affordability to a larger number of students. Do you dispute that framing?

GP: Well, to the extent you are looking at standard faculty and standard reformers, I guess that is true.

JS: But it doesn’t apply here?

GP: I don’t put us in the reformer category. I put us in the area of trying to figure out in this new world, in this paradigm shift we’re going through, what are best practices? So let’s go back and talk about those things that we’ve touched on and what things are we trying to change? So we look at affordability.

JS: Let’s talk about affordability.

GP: Across America, tuition has gone up about 140 percent over the past ten years versus what inflation is. In Texas, if you look at our numbers in the UT System, UT-Austin’s tuition has gone up about 60 percent. Some other schools have gone up 90 percent. And then you have to compare that to how much appropriations [from the Legislature] have gone down? At UT-Austin appropriations have come down 48 percent. Now those are not on comparable dollars, so when you compare the dollars, UT-Austin on that comparison is actually ahead about 15 percent. But if you look at our average, across-the-system tuition, we’re at around $8,400 dollars.

JS: For annual in-state tuition?

GP: Yes.

JS: That’s an average of all the campuses?

GP: Yeah, all the campuses. You then look at the net after grants, after scholarships, all of that. That number is about $1,600. That’s what the students are paying versus what they are borrowing and getting scholarships. Therein lies a really big problem. The delta between those two numbers is mostly loans: Pell Grants, loans from different institutions to students. The problem you’ve got is that every year in Texas you’re generating $1.4 billion in debt. Now, let’s say that some of that scholarship is not repayable, so let’s take two thirds, it’s still a billion. So we’ve asked all our schools to hold down tuition and keep it flat or keep it low. Incidentally, you need to know this because people get really upset about it and President Powers got very upset, but we have taken the money that the system has and we have paid that down. We have paid those schools for those two years.

JS: Meaning that they don’t have to raise their tuitions during that time frame?

GP: Right, we will give them the money.

JS: So even though you approve them to raise their tuitions, they don’t have to?

GP: Right, Austin wanted to raise tuition around $6 million a year. What we do is, we’re not going to let them have that, but we’re going to write them a check for that amount of money so that they will be made whole for the next two years. The other schools, we approved the tuition increase but then we go in there and pay down their tuition rather than have the students pay for it. So our goal here is to give them a two-year window to lower their cost. President Powers got very upset when we didn’t approve Austin’s tuition increase. He said some caustic things about us the day of the vote, which was May of 2012. Now, that was the same day we approved the medical school and $25 million a year for UT-Austin, and we said we want you to hold your tuition flat, but we’re going to pay you for it. In his Tower Talk that evening there were some negative comments about the board. But because of the pressure, President Powers did appoint a blue-ribbon panel. The blue-ribbon panel looked at 25 percent of the university and said, “We know how you can save $490 million, $49 million a year.” Now let’s be fair about that. A good portion is made up of fees that they would charge to students. So let’s say half of it’s fees, so let’s go back and say there’s $24 million that they saved. With that $24 million, they can pay that $6 million a year that they needed for tuition, now they’re down to eighteen. They could actually give the students a 2 percent reduction in tuition. They would be down to 12. So they would have net $12 million to put in their pocket, they would have lowered tuition or made it to where they could hold it flat.

Now what about the blue-ribbon panel? When are they going to look at the other 75 percent of the university? That’s the very first thing: affordability. How do we hold costs down? How do we challenge our schools? Here at the system, what we started doing in 2007, and we’re still doing it today, is we assigned assigned Regent Pejovich to work with Executive Vice Chancellor Kelley. We have now saved $2 billion with buying groups—putting our schools together to buy copiers or, you know, to bundle services for more buying power. And we are looking at the system, how we can help institutions lower cost. So we are pushing every place we can to lower costs because ultimately we want to lower the cost to the student. It’s not just our goal to push down costs or to cause quality to go down. The blue-ribbon panel said that these things could be done without any negative impact on the students, and that’s what we would want.

JS: Now a couple of years ago, you raised the idea that tuition should be, could be cut by about 50 percent across the entire system.

GP: That’s not correct.

JS: That’s not correct?

GP: What happened was, we had . . .

JS: I don’t mean you proposed it, I mean you raised the idea.

GP: Well, no, I didn’t raise the idea, what I said was, and this was again part of the attack . . .

JS: Well, I’m not trying to attack you.

GP: No, no, no, I’m saying that’s what they did and you picked it up, so let me explain to you what happened. We had the two task forces going and we were talking about, “Could you raise enrollment and could you lower tuition?” And I wrote a memo saying, when we come to the framework, or when we finalize the recommendations, will you have a recommendation such as lowering costs by a certain percent—like lowering costs by half and raising enrollment by 10 percent a year? Will you have that kind of recommendation? So it was an email saying, “Is this what you’re going to come up with?” And they said no. So it went in the trash can never to be thought of again, until somebody got hold of it and said the chairman wants to do this. I never said I wanted to do that, I said, “Is this what you’re going to do?” We were discussing a lot of things, but the framework laid that to rest—because the framework is what we are doing.

In part two: the roots of the “Framework for Advancing Excellence”; what the White House thinks about the higher ed reforms in Austin; the argument for increasing enrollment through online courses; the case for why the past two years in the UT System have been the most productive 24-month cycle ever in higher education in America; and more.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Higher Education

- Rick Perry

- Bill Powers