The mustang has eyes that are large and dark and betray his mood. His coat is bright bay, which is to say he’s a rich red, with black running down his knees and hocks. He has a white star the size of a silver dollar on his forehead and a freeze mark on his neck. He cranks his head high as a rider approaches, shaking out a rope from a large gray gelding. The mustang does not know what is to come. His name is Cheatgrass, and he’s six years old. In May he was as wild as a songbird.

The little horse belongs to Teryn Lee Muench, a 27-year-old son of the Big Bend who grew up in Brewster and Presidio counties. Teryn Lee is tall, blue-eyed, and long-limbed. He wears his shirts buttoned all the way to the neck and custom spurs that bear his name. He never rolls up his sleeves. A turkey feather is jammed in his hatband, and he’s prone to saying things like “I was out yesterday and it came a downpour,” or, speaking of a hardheaded horse, “He’s a sorry, counterfeit son of a gun.” Horse training is the only job he has ever had.

Teryn Lee was among 130 people who signed up this spring for the Supreme Extreme Mustang Makeover, a contest in which trainers are given one hundred days to take feral horses from the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), gentle these creatures, and teach them to accept grooming, leading, saddling, and riding. Don’t let the silliness of the contest’s name distract from the difficulty of the challenge. Domestic horses can be taught to walk, trot, and lope under saddle in one hundred days; it’s called being green-broke. But domestic horses are usually familiar with people. The mustangs in the Makeover have lived on the range for years without human interaction, surviving drought, brutal winters, and trolling mountain lions. The only connection they have to people is fear. Age presents another challenge. A domestic horse is broke to saddle at about age two, when it’s a gawky teenager. The contest mustangs are opinionated and mature. The culmination of the contest is a two-day event in Fort Worth in August, where the horses are judged on their level of training and responsiveness. The top twenty teams make the finals. The winner takes home $50,000.

How does that work, gentling a wild thing? How do you convince a nomad that a different life is possible?

For Teryn Lee, however, there’s more at stake than money. Most of his clients bring him horses that buck or bully, horses that have developed bad habits that stymie or even frighten their owners. Teryn Lee enjoys this work, but his goal is to become a well-known trainer and clinician who rides in top reined cow horse and cutting horse competitions. To step up to that level, he’ll have to do something dramatic. Transforming a scruffy, feral mustang that no one wanted into a handsome, gentle, willing riding horse would make people take notice. Winning would get his name out there, he says.

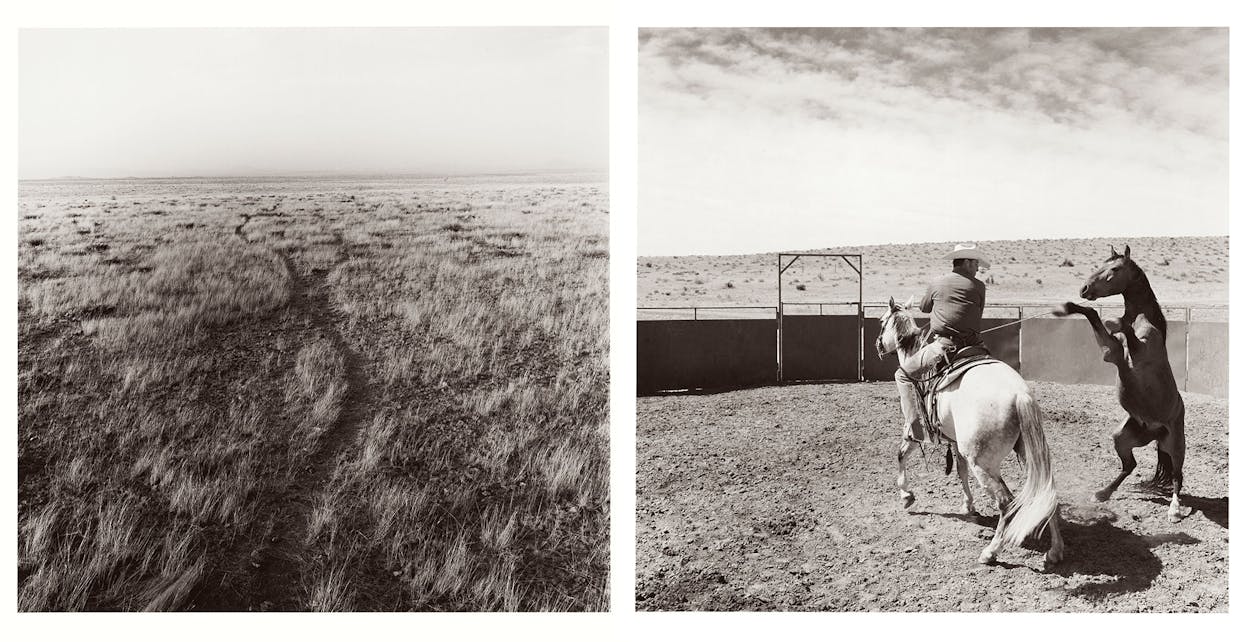

How does that work, gentling a wild thing? How do you convince a nomad that a different life is possible? Teryn Lee picked up Cheatgrass on May 8 from a BLM facility in Oklahoma and hauled him to his training operation near Marfa, a 50,000-acre ranch leased by his father and managed by Teryn Lee and his wife, Holly. Two days later, standing in a round pen, Cheatgrass looks runty and ribby, like a cayuse from a Frederic Remington painting, still wearing the BLM halter.

Teryn Lee rides a gelding called Big Gray. The mustang eyes them. Horses are prey animals that are vulnerable by themselves; as social beings, they seek out friendship. They feel safe with another horse, even if it’s a stranger. Cheatgrass allows Big Gray to step close. Teryn Lee leans down from his saddle and drops the halter off the mustang’s head.

“There,” he says. “Now he’s a wild mustang.”

Teryn Lee begins swinging a rope behind the mustang, who zips frantically around the perimeter of the round pen at a dead run, mane streaming. As Cheatgrass flies past, Teryn Lee occasionally flicks the tail of the rope into the horse’s path to make the mustang change direction. Cheatgrass nimbly tucks his knees and wheels away, deft as a cat, fleet as a thought.

“I want him to move around,” Teryn Lee explains. “Breaking a horse is all about controlling his feet. If I can control his feet, I’ve got him. Later I’ll try to touch him all over, but we’ll see. You can’t hurry a horse.”

Cheatgrass’s adrenaline slows down a tick as he considers his options. Thousands of generations of flight instinct course through a mustang, but he is also a survivor who comes loaded with a keen ability to adapt. Running away isn’t working, so Cheatgrass slows to a fast trot. He is small but spring-loaded, muscles bunching and jumping under his coat. His inside ear and white-ringed eye never leave the man deciding where he can go and how fast. With a swing or two of the rope over his head, Teryn Lee sends a loop and catches the horse around the neck. As the loop tightens, the mustang roars and rears, his hooves momentarily striking the sky. He faces Teryn Lee, sides heaving and nostrils flaring. They stare at each other. There is the sound of the horse’s breathing and the wind sliding by. Moments pass. Teryn Lee asks the gray gelding to step forward, his hand moving up the rope until the two horses are neck to neck. The loop loosens. Neither slow nor fast, Teryn Lee’s hand reaches forward and lightly rubs the star on Cheatgrass’s forehead. The first touch. The mustang is canted backward, every muscle straining, but he stands. His world has just changed.

The ranch where Cheatgrass lived this summer is high and remote, an hour from Marfa and deep within Presidio County. Great treeless hills roll and fold to the mountains on the horizon: Chinati Peak, humped and blue, not far from the ranch house; Mount Livermore and the Davis Mountains in the north; Haystack, Paisano Peak, Twin Sisters, Goat Mountain, Santiago to the east. Summer monsoons carpet the desert with grama. From most points on the ranch, no homes or roads are visible. No power lines, no vehicles, no buildings for mile upon mile—just grass, rocks, and the impassive, tenantless sky. On a high hill, with the chorus of mountains and wind all around, it’s possible to imagine these unsettled plains as they were two hundred or four hundred or even one thousand years ago: open, ancient, and achingly beautiful.

Bountiful land like this nurtured the mustang. Horses were native to North America until about 11,000 years ago, when evidence of them tapers out. They didn’t return to the main continent until 1519, when Hernán Cortés famously flummoxed the Aztecs with sixteen horses that landed with his men on the Mexican coast. More Spanish explorers, missionaries, soldiers, and settlers came, and they all brought horses. Animals that escaped or were loosed onto the prairies multiplied and changed the lives of Plains Indians, whose culture would become as fully integrated with horses as it was with bison. During World War I, ranchers responded to wartime’s increased need for horses by turning their well-bred stallions onto the range to better the native herds, which were later gathered and exported to the European front. It’s from this array of purebreds and mongrels that mustangs are descended.

Wild horses tramped across the plains and the Western United States, but Texas was their true home.

J. Frank Dobie wrote the history of America’s wild horses in his 1952 book, The Mustangs. Wild horses tramped across the plains and the Western United States, but Texas was their true home. “My own guess is that at no time were there more than a million mustangs in Texas and no more than a million others scattered over the remainder of the West,” he wrote. The mustang’s history and our own are inextricable. Mustangs galloped in Comanche raids on the Llano Estacado, pushed Longhorns across the Canadian, busted sod at immigrant farms in Central Texas, bore Texans into war. Their glory stirred souls.

Among those who chronicled the mustang in Texas was Ulysses S. Grant, who in 1846 served as a lieutenant under Zachary Taylor in the U.S.-Mexican War. Grant rode a $5 mustang. He was a few days outside Corpus Christi when word came of an immense group of mustangs near the head of the column. “As far as the eye could reach to our right, the herd extended,” he wrote in his memoirs. “To the left, it extended equally. There was no estimating the number of animals in it; I have no idea that they could all have been corralled in the state of Rhode Island, or Delaware, at one time.”

No one seems to have recorded when the last wild horse in Texas was roped and put to work. It might have been a horseman named Ben Green, who trailed a wild band from Big Bend into northern Mexico and Arizona during the Depression. Dobie closes his book by musing that the mustang’s days were over.

Well, the wild ones—the coyote duns, the smokies, the blues, the blue roans, the snip-nosed pintos, the flea-bitten grays and the black-skinned whites, the shining blacks and the rusty browns, the red roans, the toasted sorrels and the stockinged bays, the splotched appaloosas and the cream-maned palominos and all the others in shadings of color as various as the hues that show and fade on the clouds at sunset—they are all gone now, gone as completely as the free grass they vivified. Only through “visionary gleam” can any man ever again run with them, for only in the symbolism of poetry does ghost draw lover in hope-continued pursuit.

The book is a wonderful balance of scholarly research and folklore, but on the utter demise of the mustang, Dobie was mistaken. A federal law passed in 1971 protects feral horses on public lands. Today the BLM oversees nearly 34,000 wild horses and several thousand burros that graze across 26.6 million acres in ten Western states. For most of his life, Cheatgrass was one of them.

Have you studied a person who can do something well? Have you seen how effortless the work appears? Teryn Lee has that with horses. He never hurries. He never seems indecisive. He never becomes angry or worried that he’s messed up. One action to the next flows like water.

“A horse has all the qualities I’d like to possess as a human,” he said more than once this summer. “They’re curious, not corrupted. They only know what they’re taught. They’re a mirror of the person riding them.” That’s not necessarily how horse gentling has always gone. There’s a reason it’s called “breaking.” Dobie wrote that “one out of every three mustangs captured in southwest Texas was expected to die before they were tamed. The process of breaking often broke the spirits of the other two.”

Teryn Lee doesn’t follow those old, brutal ways. “Every time Cheatgrass has seen men, he’s been poked with a needle, been freeze-branded, or been castrated,” he said. “If I were him, I don’t think I’d like people very much. Horses are the most forgiving animal there is.”

On day two, not long after the sun has crested Goat Mountain, Teryn Lee walks into the pen, catches Cheatgrass by the lead rope, and rubs him steadily all over with one hand.

“Here’s where he’ll get mad,” he says, and his hand makes its way along the horse’s belly. Cheatgrass bugs his eyes and begins to quiver. His ears swivel furiously, and Teryn Lee gives him a moment. Every time the horse does what he asks—or tries to—he gives the horse a release, whether it’s a momentary rest, a stroke, or allowing it to slow. Once Teryn Lee starts an action, he carries it through very deliberately. He lets Cheatgrass sniff the saddle pad and smoothly drapes it onto his back. He rests the saddle on his hip and allows the horse to go over it with his nose, then carefully sets it on the mustang. The horse’s head is jacked up and his nostrils flutter. Slowly, the cinches are tightened. Teryn Lee slips off the halter and backs away.

Cheatgrass is frozen for two beats and then, bam, he jams his head to the earth and his shoulders to the clouds in a series of seesaw bucks. Time slows into freeze-frames: the C-shaped horse suspended in air, the hip-high dust, the rigid-legged horse pounding the ground. Just as suddenly as he starts, Cheatgrass stops and looks at Teryn Lee, his ears tipped forward.

“That wasn’t too bad!” Teryn Lee exclaims.

“We’ve had domestic colts that buck for much longer,” Holly says.

Teryn Lee leaves the horse to get used to the saddle and returns in an hour, pointing to the dust in the pen.

“You can see where he got down and rolled on the saddle a few times,” he says. “Horses can move left, right, forward, backward, up, and down. I’d like to get him comfortable moving in all those directions. He went up and down. Now I’ll have him go forward and backward.”

Teryn Lee uses his body and the flicking of a rope to move Cheatgrass around the pen: More pressure and a kissing sound from Teryn Lee means lope; stepping into his path makes the mustang change direction; turning away from the horse makes him slow or stop.

“A large part of training is feel,” Teryn Lee says. “I can feel what they’ll do before they do it. If you can’t feel it, you can’t fix it. You have to move with a purpose but be sensitive about it.”

Within a few minutes, he’s at the mustang’s side. He puts a foot in the stirrup and bounces a couple of times before standing up in the stirrup for a second or two. There’s no preamble to this—he just does it, on both sides. The horse’s mouth is clamped in a prim line.

“He’s pretty tight, but he’s taking it real good,” says Teryn Lee. “Confidence is a big thing. If he’s confident, everything else will take care of itself.”

Wild mustangs forage on land that is populated by antelope, deer, and elk and share food and water sources with domestic cattle owned by ranchers with grazing leases on public land. Nowadays they live mostly in Nevada. According to the BLM, mustangs can double in population every four years, and when there are too many horses for the available acreage, the herds must be periodically thinned.

“The land can only support what it will support,” said Sally Spencer, the head of marketing for the BLM. “The land needs to stay healthy, and the animals need to stay healthy. We want to make sure the mustangs are there for all Americans to see forever and ever.”

From BLM holding facilities, captured mustangs are carted across the country to different public adoption events. Horses in unusual colors—pintos, buckskins, palominos—are likelier to get adopted than a plain bay or brown horse. Older horses aren’t typically adopted either. Those that are deemed unadoptable are shipped for long-term holding to private ranches primarily in the Midwest, which contract with the BLM to maintain the horses for the rest of their lives.

But the BLM has received biting criticism for its gathering practices, which sometimes result in injury or death to mustangs as they’re rounded up. Mustang advocates argue that the horses are pushed off the range in favor of cattle that ranchers run on land leased from the government. Advocates also say there are too many horses in holding facilities. Cheatgrass, for instance, lived fifteen months at a Colorado short-term holding facility before being picked for the Makeover.

And none of this is cheap. The wild horse and burro program cost $63.9 million to run in 2010, 57 percent of which went to keeping horses in holding facilities. Adoption rates have fallen in recent years. “The program we have is not sustainable,” Spencer said. “We need to figure out another way the horses can be managed on the range.”

“I figured we could take talented people and turn wild horses into something that was viable as a riding or working partner. It’s a piece of Americana that you’re taking into your home.”

Madeleine Pickens, the wife of oil billionaire T. Boone Pickens, is among the people working on solutions. “The horses that are in short-term holding cost the taxpayer $2,500 per year, which is very costly,” she said. “The conditions are pretty severe, when you consider they’re animals that roamed freely and they’re suddenly put in a temporary corral. They’re only supposed to be there three months, and some are there for three years.”

Pickens is passionate about mustangs. She’s been in talks with the BLM since 2008 on her proposal to place as many as 30,000 mustangs on more than 600,000 acres of public and private lands in northeast Nevada. In the plan, her foundation, Saving America’s Mustangs, would oversee the ranch and develop it into an ecotourism facility. In return, the foundation would receive $500 per year per horse, which is about the same rate contractors receive for horses that live in long-term holding ranches on private property. According to Pickens, the deal would offer transparency that the privately run holding sites do not.

“The government has a fiscal and moral responsibility, since they’ve moved horses off of public lands,” she said. “Let’s fence it in, have a nonreproductive herd, and let the public come and enjoy it.”

Pickens sees the mustang ranch as nothing less than preserving an emblem of America.

“One hundred years ago there were two million horses on the range,” she said. “If we’re down to the last thirty thousand or so, as the BLM says, we’re getting closer to extinction, and that’s when people start to pay attention.”

That’s where events like the Supreme Extreme Mustang Makeover come in. “The research shows that if a mustang is gentled, the odds of it getting adopted jump,” said Patti Colbert, the executive director of the Mustang Heritage Foundation, which puts on the Makeover. “I figured we could take talented people and turn wild horses into something that was viable as a riding or working partner. It’s a piece of Americana that you’re taking into your home.”

The Makeover grew from a single event in Fort Worth in 2007 to eight contests held all over the country this year. The previous contests offered prizes, but mostly the winners got bragging rights. Teryn Lee earned third at last year’s Makeover in Fort Worth and walked away with two grand. Fifty thousand dollars, though, is a different story.

“I say not to think about the money,” Holly told Teryn Lee one day in the first week of training. Holly has round blue eyes, yellow braids, and an Oklahoman’s practicality. She’s an ace cutting horse rider, but she leaves the training to Teryn Lee. At any given time, he has twenty horses in training, and he rides each of them every day. While he’s riding, Holly bustles around the pens, feeding, filling water troughs, saddling her husband’s next mount, and bathing the one he’s just finished with.

“Nothing would be different if we won,” Teryn Lee said. “We’d just have more operating capital.”

“Still,” she said, “you shouldn’t count on things before they happen.”

On the third day of training, Cheatgrass is saddled and tense, pawing in frustration. The action of his circling foot is too fast for the eye to follow. He rumbles a snort.

“The third day is the worst day,” Teryn Lee says cheerfully. “They’re sore and tired of being messed with, but I think I can talk him out of bucking.”

He introduces the bridle, and there are several long minutes while he holds the bit to Cheatgrass’s mouth until the horse takes it. After a one-two-three bounce from the stirrup, he swings a leg half over Cheatgrass and then steps off. He does it again, but this time he settles in the saddle.

Cheatgrass pauses, trembles, and jettisons into bucks that roll like a current in a river. Teryn Lee sits still and yielding at the same time, his hands well in front of him and the reins not tight. The bucks decelerate into a ragged lope. At Teryn Lee’s instruction, Holly waggles a plastic flag to keep Cheatgrass going forward, because a horse moving forward is less likely to also go up. They trot and lope until Teryn Lee allows him to walk and uses the reins to gently guide Cheatgrass a few steps to the right and left. He gets off. Cheatgrass sighs.

“He got scared when I swung my leg around, but he wasn’t scared at the end and that’s what’s important,” says Teryn Lee. “That wasn’t too bad. Tomorrow we’ll ride outside.”

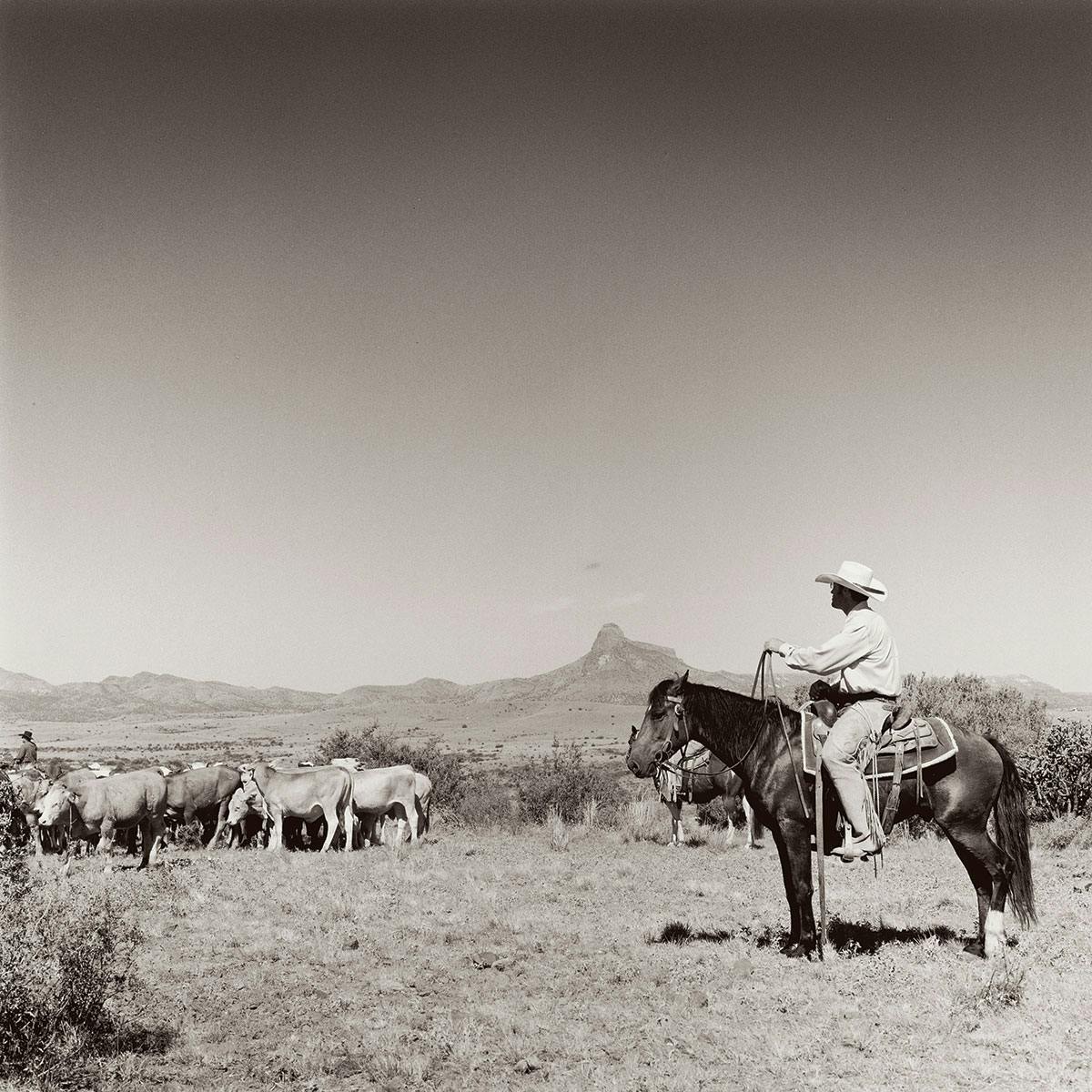

The next morning Teryn Lee hops twice in the stirrup before landing lightly on the mustang’s back. Holly waits on Big Gray as the gate swings open. Cheatgrass follows the gray at a lope down a ranch road and up a draw. Ten minutes later, they appear on a hilltop, picking their way through the rocks at a walk. Cheatgrass jigs and his tail flags behind him.

“Today he understands what is going to happen to him,” Teryn Lee says. “It’s fine for him to accept that he’s going to be doing this for the rest of his life.”

Cheatgrass was ridden nearly every day during the summer. By day ten, he moved free and soft, with simple changes in direction. By day twenty, he was loping long, straight paths across pastures. He was bathed, brushed, and shod. He was taught to back, circle, and stop. He sidestepped and snorted during bridling and saddling, but after he was ridden and turned loose, he’d follow Holly around and sidle up for a pat. He grew accustomed to ropes and squealed with excitement at the sight of cattle.

“For a six-year-old with less than forty-five days on him, he gets working cattle,” Teryn Lee said. “I didn’t think he’d enjoy it, but he enjoys the heck out of it.” In June and July, when Teryn Lee was hired to work on other ranches, he used Cheatgrass. They negotiated rocky hillsides, stepped through thorny brush, and forded water. Cheatgrass loaded into trailers and stood tied in the warm-up arena while Teryn Lee and Holly competed at shows on other horses. Word got around that Teryn Lee had entered the Makeover. Railbirds watched him trot the mustang around the fairgrounds after a show in Las Cruces, New Mexico. Cheatgrass had been in training about eighty days.

“What will he do?” one of them called out.

“He’ll tie and work off a rope,” Teryn Lee replied.

“Was he ever handled?” another asked.

“Nope.”

“How’d you get into that deal?”

“You’ve got to be willing to ride a wild mustang,” Teryn Lee said.

Kevin Hanratty, a working cow horse competitor from Lincoln, New Mexico, stood off to one side and watched too. Little Cheatgrass, with the BLM freeze mark on his neck, looked out of place next to the bulldoggy quarter horses around him. Despite the clanking, hollering clamor of the showgrounds, the mustang blinked happily as Teryn Lee chatted. Hanratty, with his jeans tucked into his stovepipe boots, was riveted. “That horse, his blood goes back to the old Spanish vaqueros,” he said. “Right there is the little bit of us that’s still wild, a remnant of the Old West. There’s not much of it left, but it’s still alive with Teryn Lee and that horse.”

Three weeks later the warm-up ring at the Will Rogers Memorial Center, in Fort Worth, swarmed with shiny-hided mustangs: red, yellow, brown, black, and gray. The challenge of training them had taken a toll. Of the 130 trainers who had signed up for the Makeover, only 83 had made it to the contest. Trainers came from 23 states. One of the top contenders was Mark Lyon, a Nebraska trainer who won the contest in 2008. He wore his red mustache waxed, like a friendly Snidely Whiplash, and a flat-crowned black hat. “They were once wild, and they’ve decided to become willing partners,” he said. “They’re the forgotten horse.”

Many of the animals showed little evidence of their wild days. Day campers visiting the horse barns lined up to meet a black mare. Three months earlier, she had never felt human touch. Now she lowered her head and half-dozed as little hands patted her all over. Nearby, Victor Villarreal waited for his next class with his blaze-faced mustang, Cochise. Villarreal lives in Fairfield and works at a power plant. Unlike Teryn Lee, he’s not a professional trainer. “I’m just a regular joe who has a passion for it,” he said. “How many people can say they’ve trained a wild mustang?”

In the two-day contest, the horse and rider teams qualified for the finals by competing in four preliminary classes, where the difficulty of what they’d attempted became clear. Some horses trotted through cones but refused to go through the gate obstacle in trail class. Some docilely lifted their feet on their trainer’s cue but freaked at the sight of a flag. Others didn’t stop too well. There were horses that jerked, stamped, and said no. Several riders very nearly got dumped.

There were also successes, teams like Cheatgrass and Teryn Lee that demonstrated an abiding understanding of each other and traveled the classes on a loose rein, relaxed. Cheatgrass did everything he was asked, stopping and turning and accepting commands despite the indoor spaces he’d never seen before, the crowds, the noise. Teryn Lee’s strategy was simple. “I don’t have to win every class,” he said. “I just have to make the top twenty.”

Amid the thrill of competition, the BLM made sure to get its message out. Not far from the vendors selling halters and miracle supplements, Don Glenn, the director of the wild horse and burro program, sat behind a table laden with mustang trinkets and promotional materials.

“We can’t allow the wild horse to expand and let nature take its course,” he said. “They’ll destroy their own habitat and die from lack of food and water. Congress has passed laws to allow for livestock grazing and mandated for multiple-use management not just for horses, not just for cows, not just for wildlife or oil and gas but for all those things.”

It was late in the afternoon of the contest’s second day. In a few minutes, judges would announce the twenty finalists, who would compete that evening, including Teryn Lee and Cheatgrass.

“This has been the highlight of the wild horse and burro program,” Glenn said. “This effort gets more horses adopted. The last thing we want is for the mustang to disappear.”

There is something that happens when horses travel loose together. The finals began with the National Anthem in four-part harmony. The gates of the coliseum opened and eight mustangs of eight colors flowed out, followed by a cowboy snapping a bullwhip. They moved in unison as seamlessly as birds in flight, necks arched, manes floating, shifting speed and direction by some unseen communication known only to them. It was hokey, it was sentimental, and, reader, it was beautiful.

Each finalist had four and a half minutes to show off his or her horse to music. Judges looked for horses with the basics of walk, trot, and lope, along with several other maneuvers. They also judged the riders’ horsemanship and the overall presentation of the performance. Props were encouraged. Several contestants dressed as Indians, complete with braided wigs, one of whom leaned over at a lope and snatched up what appeared to be a blow-up doll dressed as an Indian maiden. He set the stolen maid on the back of the horse, where she flapped gracelessly against the horse’s rump at every stride. One rider, dressed as a firefighter, did a tribute to U.S. service members and first responders. This got big applause. Another finalist eschewed music and rode to an original spoken-word piece from the point of view of her buckskin horse, Tucker. At one point in her routine, she laid the horse down on the arena floor in front of all those thousands of people. She got on her knees, leaned against him, and prayed.

“I am the creator’s gift to you,” the voice-over said earnestly. “I am mustang. I am Tucker the mustang.”

Shooting was popular in the finals, the extremely loud ka-pows apparently demonstrating the animals’ tolerance for the unpredictable array of human antics. But a few routines were less scripted, and these unadorned performances best highlighted the achievements the teams had made. Horses chased calves with all the speed they had. There were riders who stood on their horses’ backs or rode without bridles. One mustang docilely carried the young daughter of the trainer at the end of her performance.

Under the blaze of Will Rogers’s lights, very far from the deserts of Utah, where he was born, Cheatgrass the wild horse loped out and stopped neatly at the end of the arena. He turned in a careful spin, collected himself, and loped large, even circles. Teryn Lee gunned him a bit, then Cheatgrass made a long, sliding stop. When a calf was sent into the arena, the mustang’s ears stood at pert attention. He dodged when it dodged and skittered when it skittered. He tracked the calf as Teryn Lee built a loop and caught it with a minute to go. Other finalists had done this much, but Teryn Lee dropped off the side of the horse and ran down the rope to the calf, flipping it onto its side and tying its feet as it flopped and struggled. Cheatgrass backed up and kept the rope taut, as a little calf-roping horse should. His eyes never left Teryn Lee and his feet did not move. People in the stands thundered applause and rose to cheer until the music was hard to hear; the mustang stayed at his job until Teryn Lee mounted, slacked his rope, and tipped his hat to the stands as they walked away. It’s not what horses with a hundred days of handling are supposed to be able to do.

When Teryn Lee’s name was called, he dropped his head and rubbed his mustang’s neck. A colored sash was thrown over Cheatgrass. Teryn Lee, looking a little stunned, gripped the $50,000 cardboard check as he was mobbed by well-wishers. Photographers posed him with judges and rodeo queens in spangled suits.

“He has a home with us forever,” he told anyone who asked.

They had won the highest purse ever awarded in a wild horse competition. Cheatgrass stood quiet amid the flash and hubbub, his eyes dark and soft. He’s a mustang. He does not know what is to come.