Iassume the Secret Service agents will arrive first, checking out everyone in sight. But suddenly the door opens, and in she comes, all alone, dressed casually in an inexpensive gray dress with a matching cotton sweater, her sandy-blond hair held back with a rubber band.

“So is this okay? Mexican food?” asks Jenna Bush. “I figured it might make you feel more at home.”

It’s a mild July evening in Washington, D.C., and Jenna has agreed to meet me for dinner at the upscale Oyamel Cocina restaurant, between the Capitol and the White House, where Jenna is, as she likes to say, “living with the folks.” When I ask her why her Secret Service detail is not with her, she shrugs and says, “I made them drop me off at the corner. I don’t want to cause a scene.”

At 25, she is a striking, slim young woman, her arms and legs perfectly toned thanks to daily 6 a.m. workouts at the White House gym or a health club she frequents. She is also unmistakably her father’s daughter, with the same brown eyes, the same good-natured grin that slides sideways across her face, and, yes, the same saucy personality, full of sardonic asides.

“Oh, by the way, Dad was going to call and say hi, but then the king of Jordan called,” Jenna tells me. “Sorry you got bumped.”

“What do you think your dad’s doing right now?”

“Riding his bike around the White House lawn. He’s a maniac on that bike.”

“And your mom?”

“She’s probably in the sitting room on the second floor, reading. We got the new TEXAS MONTHLY, by the way. I saw you had an article in there. All I have to say is, I hope you write a better one about me.”

She chuckles, and a few diners at nearby tables glance her way. Over at the bar, a couple of young men in suits openly gape at her. Although Jenna has lived in Washington only since graduating from college in 2004, she is one of the city’s genuine celebrities. Her twin sister, Barbara, who lives in New York City, is rarely recognized when she goes out in Manhattan. But being a Bush in Washington is a far different experience: Jenna cannot show up anywhere without later seeing her name in a gossip column or on some snarky blog. Just a week before our dinner, there had been an item in the Celeb Sightings section of the Washington Post’s Names and Faces column claiming that Jenna had been spotted at a trendy restaurant eating foie gras. The news had set off a minor controversy, prompting the president of People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, Ingrid Newkirk, to fax a letter to Jenna at the White House, angrily describing the grisly conditions ducks must endure at duck farms. “It’s simply un-American,” Newkirk wrote. “Will you commit to never eating foie gras again?”

“Foie gras,” says Jenna with another chuckle, shaking her head back and forth in mock exasperation, just as her father does when reporters ask him what he thinks are stupid questions. “Where did they come up with that? The only meat I eat is fish.”

A waiter appears, and Jenna orders a small dish of ceviche, a small dish of beans, guacamole, and a glass of water with no ice.

“No drink?” asks the waiter.

“No drink,” Jenna firmly says, shooting me an amused glance. “I’m making it an early evening. Actually, these days, I almost always make it an early evening. I like to be in bed reading or watching a movie by nine o’clock, and I’m asleep by ten or ten-thirty.”

She notices the skeptical look on my face and shakes her head again. “People change, you know.”

Boy, do they. Flash back to December 2000, not long after her father eked out a victory in the presidential election. There, in the National Enquirer, was a nearly full-page photo of Jenna, then a nineteen-year-old freshman at the University of Texas at Austin. She had a cigarette in her hand and was laughing hysterically as she crashed to the floor atop a female friend at a party.

“Get Ready, America!” blared the Enquirer’s headline. “Here Comes George W.’s Wild Daughter.”

Then, a few months later, Jenna was cited for underage drinking at a bar on Austin’s Sixth Street. Within weeks she was cited a second time for underage drinking, this time with Barbara, who had just completed her freshman year at Yale. Now the mainstream press paid attention, and suddenly Jenna and Barbara found themselves heralded, and derided, from coast to coast as America’s new party girls.

Jenna got the brunt of it. Jay Leno joked that her Secret Service nickname was Roger Clinton, that she was learning to play a new musical instrument: the Breathalyzer. High-brow op-ed columnists piled on, purporting to psychoanalyze Jenna, arguing that her antics were acts of adolescent rebellion or signs of deeper emotional issues. One went so far as to suggest that Jenna had the same kind of drinking problem that had afflicted her father when he was younger.

Well, America, get ready again: Here comes George W. Bush’s mild daughter. You can still find her having the occasional drink with her friends at a happening nightspot in Georgetown or hanging out at the Iota Club and Cafe, in Arlington, Virginia, where she likes to listen to live music (especially by Larry McMurtry’s son, James), but she’s begun to behave like, of all things, an adult. As nearly everyone knows by now, Washington’s most eligible bachelorette recently took herself off the market: In August the White House announced that Jenna would be marrying Henry Hager, the son of a former lieutenant governor of Virginia.

Even more surprising, she’s now a big-time author—and an activist. Jenna, who since 2005 has been teaching at an elementary school in a low-income D.C. neighborhood, has written a book that she says is meant to be “a call to action” to young Americans. Ana’s Story: A Journey of Hope is about an HIV-positive seventeen-year-old single mother whom Jenna met in 2006 when she took nine months off to work as an intern with the Latin American division of UNICEF, the United Nations’ program for children in need. Most of the book is a straightforward narrative about Ana’s struggle to find happiness while battling her disease, as well as severe abuse, neglect, and poverty. But in the final chapters, Jenna not only offers teenagers detailed advice about how to avoid contracting HIV, she tells them what to do if they’re physically or sexually abused. She exhorts them to help other kids in their own communities who have been neglected or mistreated, and she encourages them to spend their summer vacations working with groups like UNICEF or Habitat for Humanity.

The book’s publisher, HarperCollins, was so impressed with Ana’s Story that it reportedly ordered a first printing of a whopping 500,000 copies. By the time you read this, Jenna will be in the middle of a nine-week, cross-country promotional tour. Most of her time on the road will be spent visiting schools, where she says she wants “to increase kids’ awareness of other young people around the world—to help them learn about the challenges they face and how they can triumph over adversity.” But she’ll also have sat down with a few big-brand interviewers, including Diane Sawyer, of ABC News, and Larry King, of CNN.

Jenna insists there’s no hidden meaning to her emergence as an individual in her own right—“I hope people think of me as someone who loves kids and who wants to make a difference,” she says—but the media are back on the psychoanalysis beat. It has not gone unnoticed, for instance, that Jenna is doing exactly what her father once did: moving past her “younger, wilder” days, to use his own infamous description, to find purpose in her life—and, by the way, doing it at 25 rather than 40, which was when her father quit drinking and righted himself.

The lit crits, meanwhile, have come after her in full force. Some have put out the word that Ana’s Story reads more like fiction than nonfiction (Gawker.com: “Is Jenna Bush the New James Frey?”), while others have implied that Jenna, a first-time author, wasn’t competent enough to do the book without a ghostwriter (Entertainment Weekly: “The book is good. Maybe too good. We have a hard time imagining that she wrote it herself”).

As for the engagement, some Bush haters claim it’s nothing more than a crass political ploy, with the ceremony being rushed so that the president can get some positive press before his term expires. One catty Washington blog, Wonkette.com, speculated that the only reason Jenna is getting married is because she’s pregnant, and it has published pictures of her at odd angles, supposedly showing her stomach pooching out. The peacenik left, meanwhile, maintains that no matter the reason for the wedding, Jenna’s new husband should immediately be sent to Iraq so that the Bushes can finally understand firsthand the real impact of the war on American families.

Predictably, Jenna has also resurfaced as a favorite punch line of the late-night comedians. Conan O’Brien: “Jenna’s written her book for children, which is a good thing. Now her dad will be able to read it too.” David Letterman: “It’s going to be an expensive wedding. I guess it’s no surprise the three-billion-dollar contract is going to Halliburton.” Jay Leno: “Jenna announced her engagement two weeks ago, although President Bush knew about it over a month ago from some wiretaps.”

“I hope people will put politics aside and see the bigger picture,” Jenna says. “But I have to tell you, sometimes I say to myself, ‘A year and a half and counting.’”

“A year and a half?” I ask, and then it hits me: On this evening, that is exactly the amount of time the Bushes have until they leave the White House and return to private life. That is also the amount of time before Jenna and her sister are no longer presidential daughters.

“A year and a half,” Jenna says, giving me another grin. “Then we’ll get to watch people make up things about someone else’s kids. Now that would be a change, wouldn’t it?”

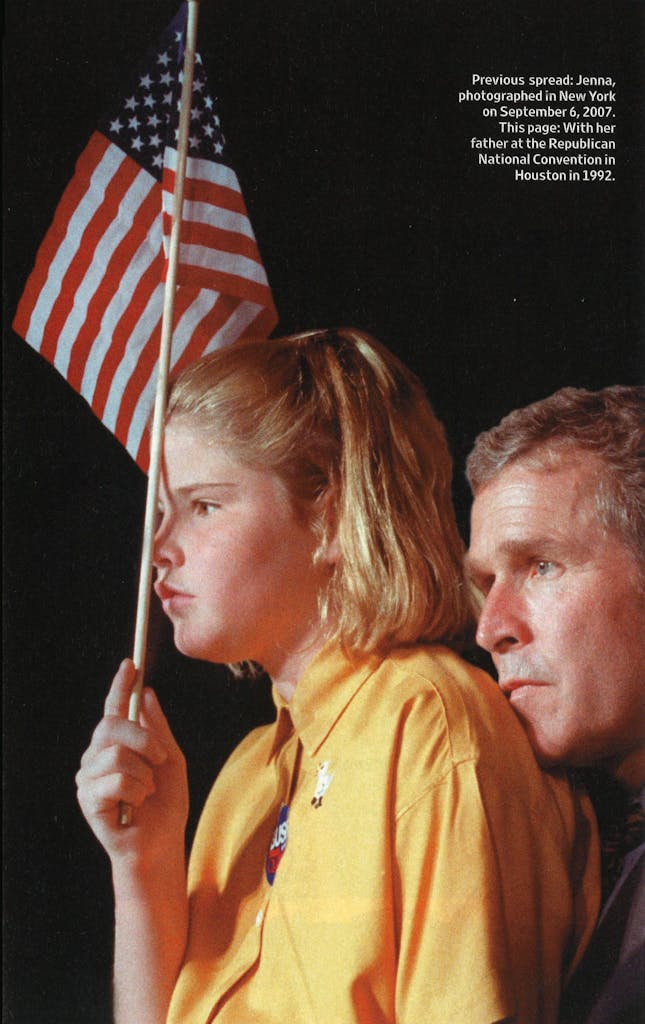

It’s no secret that presidential children lead atypical lives during the years their fathers are in office. It’s certainly no secret to Jenna’s own father. When George Herbert Walker Bush was elected president, in 1988, George W. asked a family adviser, Douglas Wead, to research what happens to presidential children. “He was going through one of his rare moments of existential self-reflection,” Wead recalls, “and he said, ‘So what happens to me now?’”

Wead produced a 44-page report noting that some presidential children had led exemplary lives: They had written books, founded corporations, headed fine educational institutions, and won political office themselves. But many more were burdened with higher-than-average rates of divorce and alcoholism. Some seemed bent on self-destruction, haunted by their inability to inhabit their own identities. The stories of most presidential children, Wead concluded, were “overwhelmingly dark.”

At the time, Wead says, Bush “shrugged off the report. He didn’t believe in curses. He didn’t believe that whatever happened to other presidential children in history had any meaning for him in the present.” And sure enough, though Bush seemed to be the archetypal underachieving presidential son, he did find his footing, assembling the group of partners who purchased the Texas Rangers in 1989 and then winning the 1994 race for governor.

But in 1998, when he was leading in presidential preference polls for the 2000 election, Bush told Wead (and many others) that he probably wasn’t going to run for one reason: He didn’t want to ruin his daughters’ lives. If he won, he said, they would be thrust into the public eye at the very moment they were entering college. They would have Secret Service agents following them. They would have to deal with all kinds of stress. Besides, he said, the girls didn’t want him to become president. If they got out of line just one time and the press got wind of it, God help them.

I’ve always wanted to know just how close Bush came to calling off his presidential run because of the girls. Was he genuinely worried that they would turn out to be like so many of the children mentioned in Wead’s report? But I assumed I would not be interviewing him for this story: The president and the first lady have maintained a strict no-comment policy about the twins, insisting that they deserve their privacy, regardless of their behavior.

Then, on the night after my dinner with Jenna, the phone rings in my Washington hotel room. “Hey,” says Jenna, “hold on a minute”—and she passes the phone to someone else. Suddenly I hear that familiar voice . . .

“Skipper!” the president says, using the nickname he gave me when I met him during his first gubernatorial campaign. On this very day, the pollsters for the Washington Post and ABC News had reported that 65 percent of Americans disapprove of Bush’s job performance, which makes him the second-most-unpopular president in the history of modern polling (just behind Richard M. Nixon’s 66 percent disapproval rating). What’s more, the front pages of various newspapers are full of stories about members of Congress calling for the resignations of various Bush staffers and attacking Bush’s handling of the war. Some on the fringe are even invoking the i-word: “impeachment.” Yet perhaps because he knows I’m writing about Jenna, he is completely ebullient. He asks how my wife and daughter are doing—amazingly, he still remembers their names, even though he hasn’t seen them since 1996—and, just like Jenna, he jokes about my writing. “What? You haven’t written a book yet?” he chortles.

When I reply that Jenna is already a far more accomplished writer than he is, that her book is better written than his campaign autobiography, A Charge to Keep, he says, “You can blame Karen [Hughes, Bush’s longtime adviser, now an Undersecretary of State] for that. She wrote it.”

I ask him if he’s nervous about one of his daughters finally stepping into the spotlight. (Barbara, who works in the educational programming division of the Cooper-Hewitt design museum, in New York City, has told me she is happy remaining as anonymous as she can.)

“Yeah, a little,” he says. “I was worried about Jenna being exposed.”

“Exposed to what?”

“Reporters like you,” he cheerfully snaps. “But really, I cannot tell you how proud I am of her for going out on her own and writing this book. I’m bursting with pride over both Jenna and Barbara. They are very capable, intelligent, and engaging young women, and they are accomplishing a great deal with their lives.”

Then he says, “Okay, that’s enough for your story. I don’t want this to be about me.”

I try to get in a question about his anxieties regarding the girls when he was first running for president, but he’s already moved on. “I’ve got to go eat,” he says. “Mrs. Bush is yelling at me, and you know what happens when she yells at me. All right, dude, I’ve got to go.”

Even as a child growing up in Dallas, Jenna was known as the rowdy twin. My stepdaughter went to the same elementary school that she and Barbara did, and when I ask her about those days, she says Barbara was bookish and Jenna was always talking up a storm as she walked the hallways between classes. Barbara agrees. “Jenna was definitely louder and funnier and more outgoing,” she told me, “and I was like my mother: quieter, more reserved.”

At Austin High School, which the twins attended during their father’s gubernatorial years, Jenna was wildly popular. “She was this great character, really funny, like a stage comedian, and a bit of a klutz who’d fall out of her chair,” recalls one of her friends. She was constantly dating—one year she invited three guys she had gone out with to the same Christmas party at the Governor’s Mansion (including Blake Gottesman, for a time one of the president’s trusted aides)—and she did her share of partying. According to the Houston Chronicle, Jenna was involved in what the newspaper described as “a Texas Alcoholic Beverage Commission incident” at the age of sixteen, the first of three such underage incidents. During Bush’s inauguration party to celebrate his reelection as governor in 1998, Jenna and Barbara slipped away to go out with their friends, and their ticked-off father stayed up until two-thirty in the morning calling various parents and trying to find them.

Jenna is deeply nostalgic about her Austin days. “It was a time when we could all walk as a family from the Governor’s Mansion to Manuel’s [a Mexican restaurant on Congress Avenue] and no one noticed us—or if they did notice us, they didn’t care,” she says. The Bushes had dinner together almost every night, and the conversations, according to Jenna, were free-flowing. She didn’t hesitate to challenge her dad: During one dinner, she plunked her fork on her plate, told him that the death penalty was wrong, and argued that the convicted killer Karla Faye Tucker should not be executed. (Her father listened respectfully, she says, but told her he would not be granting Tucker a reprieve.)

At the end of their senior year of high school, the more stylish Barbara was voted “most likely to appear in Vogue” by her classmates, while Jenna was voted “most likely to trip at the prom.” By then, Bush was running for president, and Jenna admits she and Barbara were not happy about it. “We were really independent kids, and the thought of Secret Service agents following us all the time was terrifying,” she says. “But when it came right down to it, we thought, ‘He should run because he would be a great president.’ How unbelievably selfish would it have been for us to say, ‘Please, Daddy, don’t do it because we’re nineteen and it might affect our life negatively.’”

The Bushes were so determined for the girls to lead normal lives that they kept them out of sight during the entire campaign and asked the Secret Service not to hover over them while they attended classes or hung out with their friends. Then, after the election, the president made it clear to the press corps that there would be hell to pay if he discovered that reporters were prying into Jenna’s or Barbara’s life.

As a result, except for the Enquirer story, there was nothing written about the twins—until February 2001, just one month after Inauguration Day, when it was learned that Jenna had persuaded her Secret Service detail to drive to the Tarrant County jail in Fort Worth to pick up one of her male friends who had been busted for underage drinking during a fraternity party at Texas Christian University. The story was funny. You had to admire her chutzpah. And it was hard not to laugh again, a couple months later, when the news broke that Jenna’s agents had allowed her and a friend to go into Cheers Shot Bar, on Sixth Street in Austin, even though they were both under the legal drinking age. The agents were sitting in a car outside the bar when, to their dismay, they saw a couple of undercover Austin cops cite Jenna and her friend for that dreaded teenage offense: MIP (minor in possession of alcohol).

Underage drinking is, inevitably, a fact of life in a college town like Austin. Some faculty at UT estimate that 90 percent of the school’s 49,000 students drink alcohol. The year Jenna got her MIP, there were some five hundred alcohol-related citations issued in Austin to people under the age of 21. Still, none of them was the child of the president of the United States. Everyone couldn’t help but wonder why Jenna would take a risk like that, knowing what kind of publicity would come her way if she got busted. “To be honest with you, I didn’t feel that guilty about it,” she says. “I was determined that I was not going to stay in my dorm room and do nothing after my dad had been elected. I wanted to do what other people in college do and have experiences.”

But then, in late May 2001, only a scant two weeks after Jenna went to court to plead no contest to the first MIP—for her court appearance, she wore a black tank top, pink capri pants, sandals, and a toe ring—she, Barbara, and a friend showed up at Chuy’s on Barton Springs Road, in Austin, a restaurant that the Washington Post later described as “a joint known for mediocre food and killer margaritas.” The waitress asked everyone at the table for identification. And here’s where Jenna made her big mistake. Although she surely had to have known that she was UT’s most famous female student, she pulled out a fake ID. After recognizing her, the manager, Mia Lawrence, told her she would not be served. When Lawrence realized Barbara was also at the table, she called 911 to say that there were minors on the premises attempting to purchase alcohol.

Lawrence could easily have said to Jenna and Barbara, “Girls, get out, you can’t drink here,” and that would have been that. If you’ve been to Chuy’s, you know that college kids trying to buy drinks are not exactly an endangered species. How often does the manager call 911? Clearly, Lawrence wanted to narc the twins out. (According to the police report, she told an officer, “I want them to get into big trouble,” a statement that led to much speculation among Austin Republicans that Lawrence was a Democrat.) Then, in a scene straight out of a Hollywood comedy, the cops arrived, and Jenna’s and Barbara’s Secret Service agents, no doubt imagining the end of their careers, sped out of their cars hoping to bust up the bust. One agent promised the cops that the twins would leave. But after several calls between Austin police officers, commanders, and even the chief, the decision was made to go ahead with the citations.

The media firestorm was almost instantaneous. Within days, the Austin Police Department had received more than four hundred phone calls from reporters. The tabloids, of course, had a field day (the New York Post’s front-page headline read, “Jenna and Tonic!”), and the late-night comedians nursed the story for months. (“It was a long, dull speech,” David Letterman said after one of President Bush’s State of the Union addresses. “Halfway through, Ted Kennedy sent drinks over to the Bush twins.”) On the Fox News Channel, Bill O’Reilly insisted the story was worthy “because [teenage drinking] is a very difficult problem that touches almost every American home.” Meanwhile, political reporters suggested that the twins’ antics were distracting the president from more-pressing matters.

Historians quickly thought back to Ulysses Grant’s teenage daughter, Nellie—“probably the most attractive of all the young women who have ever lived in the White House,” one wrote—who at sixteen was cavorting with so many Washington men that her parents sent her on a long trip abroad. (It didn’t work. She met an alcoholic con man in England and married him.) And to Teddy Roosevelt’s flamboyant daughter Alice, who smoked cigarettes in public—she once smoked on the rooftop of the White House to defy her father—and flirted shamelessly with any number of men, single and married. Alice, described by one newspaper as “Washington’s other monument,” was such a live wire that President Roosevelt once said, “I can either run the country or attend to Alice, but I cannot possibly do both.”

Luckily for Nellie and Alice, there were no blogs, cell phone cameras, or paparazzi back then. No presidential child, not even Chelsea Clinton, has had to contend with the peculiar mix and relentless proliferation of media outlets that the Bush girls face daily. Indeed, after the Chuy’s incident, dozens of Web sites promised up-to-the-minute coverage of their every move. (“My favorite memory of Jenna Bush,” wrote one Internet sophisticate, “is of her belching really loudly a few times in a row and then vomiting in the club bathroom.”)

Although the president refused to comment on the attention his twins were getting, an angry Laura Bush did tell CNN, “If we never saw their pictures in the paper again, we’d be a lot happier.” But she wouldn’t say anything more. (And still won’t. The first lady refused my requests for interviews, probably sensing, correctly, that the first thing I’d ask her is “What in the world did you say to your girls after that Chuy’s deal?”)

Today, Jenna is hesitant to rehash the episode, though she says she spoke to her father “right away.” “Believe me, right away. I felt terrible because I had caused problems for my parents. That’s not to say I didn’t feel I had made a mistake. But I wasn’t that devastated. I was a nineteen-year-old girl in college. A lot of my friends got MIPs. What really bothers me is that people still judge me on one thing that happened seven years ago.”

In fact, it was practically impossible for both Jenna and Barbara to shake off their margarita-swilling reputations. As the years passed, many people regarded them as frivolous young women with no real ambitions. After they turned 21, stories regularly appeared in the glossies, the tabloids, and the gossip columns about their comings and goings at chic nightclubs, Hollywood parties, and, at one point, a karaoke bar, where Jenna supposedly belted out “Sex Machine,” by James Brown. One report had her hanging out with Sean “P. Diddy” Combs in Saint-Tropez. The young actor Ashton Kutcher told Rolling Stone that after meeting Jenna and Barbara in Los Angeles, he took them back to his house, where they had drinks, and he later found them upstairs with one of his buddies, who was, in his words, “smoking out the Bush twins on his hookah.”

They did seem more comfortable in any setting other than a political one. They never made any public appearances during their father’s first term. In 2002, when Jenna flew to Europe with her mother on her first state visit, she wore corduroy pants with tattered hems and a T-shirt that exposed her midriff—not that people could tell. To avoid photographers, she hid behind garment bags held up by White House aides.

Such behavior led Ann Gerhart, a writer at the Washington Post and the author of The Perfect Wife, a best-selling 2004 biography of Laura Bush, to acidly describe the twins as having “all of the noblesse but none of the oblige”—pampered blue bloods who had shown “little interest in any of the pressing issues their generation will inherit nor shown empathy for the struggles facing their mother and father.” President and Mrs. Bush, Slate columnist Michael Crowley added, were “permissive, laissez-faire parents more interested in shielding their daughters from prying eyes than in drumming solid values into them.”

Jenna freely admits that she has never cared about politics. “I just wasn’t interested, and I’m still not interested,” she says. Nor was the obligation of upholding the family’s good name—“the Bush legacy,” as I referred to it—ever impressed upon her. “Legacy?” she asks, with obvious irritation. “The word bothers me. It’s not like my father or my grandparents had some path in mind that they wanted us to follow. They nourished any passions we had without trying to control them. They let us find our own paths, and to me, that’s the perfect way to parent.”

What rarely got reported was Jenna’s academic achievements. An English major, she did very well at UT (as did her sister, a humanities major, at Yale—unlike you-know-who). “Some people major in English to get away with some easy classes,” says UT English professor and TEXAS MONTHLY writer-at-large Don Graham, who taught Jenna in his Life and Literature of the Southwest course. “But Jenna was serious, someone who genuinely liked to read and had very good taste in the books she chose. She wrote a paper for me on Katherine Anne Porter [the Texas-born short-story writer and novelist] that was one of the more memorable I had ever received from a student.” Graham says Jenna was also intellectually curious. He took his class one day to Scholz Garten to meet the Australian novelist Frank Moorhouse, and she immediately began asking him questions about his career. “She bought him a beer,” Graham recalls. “I thought, ‘Oh, God, here comes another international incident,’ but my wife told me later that Jenna had already turned twenty-one.”

When Jenna graduated, she was planning to move to New York; live with her best friend from UT, a photographer named Mia Baxter; and start teaching at an elementary school. But after dreaming that her father had lost his bid for reelection, she called Barbara, and the two of them decided, for the first time, to get involved in one of his races. It wasn’t heavy lifting: They gave a few interviews, posed in evening dresses for Vogue, and traveled the country in a van, speaking to campaign volunteers and young Republicans. Even if Jenna didn’t like politics, she had a knack for it. “Dad says this is going to be his last campaign,” she would say, before adding, “Thank God.” She’d tell lots of funny stories about him, including one in which he refused to leave a Texas Rangers game until the last out, even though the temperature was 108 degrees. “He’s always supported his team until the very end,” she’d say (a rather prophetic comment when you consider his current troubles). Of course, Jenna being Jenna, she playfully stuck her tongue out at reporters one afternoon while driving away from a rally. And, reporters being reporters, they made hay of it. A writer for the New York Times suggested that her act of rebellion may have “reminded voters of her father’s reputation as a frat prankster, which may not be the image that his campaign wants to rekindle in a time of the war on terror.”

After the election, Jenna changed her mind and decided to live in Washington. She moved into an apartment in Georgetown with three roommates (two of whom she knew from Texas) and took a job as an assistant teacher for $36,000 a year. She asked her parents for, and received, her own SUV to drive herself back and forth to the Elsie Whitlow Stokes Community Freedom Public Charter School, which is seventeen blocks north of the White House. (Her Secret Service agents follow close behind.) The school has 250 students, 90 percent from low-income homes. Jenna has thrown herself into the job completely, dressing as the Cat in the Hat on Dr. Seuss’s birthday, leading an after-school book club to help struggling readers, taking her class to the White House at Christmas to see a screening of The Chronicles of Narnia and to play with Barney, one of the president’s dogs.

“I admit, we were a little worried about what was going to happen,” says Bobby Caballero, the school’s dean of students. “We were worried that we were going to get a lot of public attention, and we didn’t know how the kids would react to the president’s daughter being here. So one day we had a question-and-answer session with Jenna and the kids. They asked her questions like ‘Is your dad rich?’ and ‘Have you ever ridden in a limo?’ And then, when it was all over, they pretty much forgot about who she was.”

“Sometimes,” says Jenna, “I still have kids ask me, ‘Miss Jenna, what would happen if I Google you?’ And I say, ‘Oh, please, please, no, don’t do that. ’”

During one of my days in Washington, I visit Jenna at her school, where she’s teaching a summer writing workshop to eleven Hispanic and African American fourth- and fifth-graders. She’s wearing what she tells me later are her “teacher’s clothes”—a beige shirt, linen pants, and brown loafers that she bought at Target—and on top of her desk is the big backpack that she uses to carry her books and the salad she buys for lunch each day at Whole Foods.

“All right, guys,” she says, holding up Journey to Jo’Burg, a children’s book about the life of a South African family. “Who can tell me why the black families are protesting?”

A boy named Gustavo raises his hand. “Because the white people are treating the black people like . . .” He hesitates before finishing the sentence.

“Like what?” Jenna asks. “You can say it.”

“Like trash?”

“Exactly, Gustavo,” Jenna says, nodding her head. “Like trash.” She walks to the blackboard and writes the word “segregation.” Then she writes “apartheid.” “This is what happens whenever white people treat black people, or people of color, like trash. And whenever there is segregation or apartheid, what must we do?”

She writes the word “protest.”

“Protest,” says one of her students obediently.

“Now,” Jenna says, “I want everyone to take out their Freedom Writers’ Journals and write a meaningful sentence using the word ‘protest.’”

I sit back, amazed. Who could have imagined George W. Bush’s daughter teaching inner-city kids something so politically correct—so liberal—as the principles of social justice? Have I stumbled into Jenna Kucinich’s class?

“All right,” she says a few minutes later. “It’s time for Journalists’ Club. How is everyone doing on their stories for the weekly newspaper?”

After class, I pounce. “You’re teaching your kids to be reporters? Have you told your dad you’re out here creating a new generation of journalists?”

“Hey,” she says, “journalists do good things.” She pauses and stares at me, pursing her lips. “Well, most journalists, anyway.”

In late June 2006, Amy Argetsinger and Roxanne Roberts, who write the Washington Post’s popular Reliable Sources gossip column, broke the news that Jenna was taking a leave from teaching to accept an internship in UNICEF’s Latin American office. They seemed devastated. Jenna, they wrote, “is skipping the country and bidding a happy adios to the young-Washington social scene she once ruled. Uh-oh, what do we do now?”

Jenna says her decision to work for UNICEF was largely inspired by her sister’s experience volunteering for nine months at an AIDS hospital in South Africa. (Apparently there was some oblige after all.) Barbara had told Jenna that her time at the hospital was so life-changing that she sometimes felt she should still be there, finishing the work she had begun. But Jenna also wanted to go, she admits, because she had tired of Washington’s endless political chatter—and of people wanting to get close to her only because she was a Bush. “I was ready for some anonymity,” she says.

Ostensibly, her job was to work out of UNICEF’s headquarters in Panama, learn about its work, interview kids in different countries about their particular adversities—AIDS, hunger, child labor—and then write articles for the organization’s Web site. And, indeed, in the first few weeks of her internship, she traveled to a drought-stricken area of Paraguay and to urban slums in Argentina. But she could not stop thinking about a teenager she had met along the way. “We were at this meeting for women living with the HIV virus,” says Jenna’s friend Mia Baxter, who had also signed up for the program and who lived and worked with Jenna, shooting photos of the children Jenna interviewed. “This teenager stands up, holding her baby, and says in a clear voice, ‘We’re not dying from HIV. We’re living with HIV.’ I looked at Jenna. We both started crying.”

Jenna began meeting regularly with the teenage mother—in the book, her name has been changed to Ana to protect her privacy—and learned how her parents had died of AIDS, how she was sexually abused by a man at her grandmother’s house, how she spent many painful years in an orphanage, and how she fell in love with a boy for the first time and became pregnant after a single night of unprotected sex. “She was seventeen, but it seemed like she had lived a hundred years,” Jenna says. “She was this girl wearing a T-shirt and sparkling earrings, but she was so much more of a woman, with a gracefulness that I certainly didn’t have at that age.”

One day, Jenna walked into the office of Mark Connolly, the senior adviser to the UNICEF regional officer for Latin America and the Caribbean, and said she wanted to write a book about the young mother. It was an impulsive decision: Jenna had never written anything other than a few poems and papers in college. “I was encouraging, of course,” Connolly recalls, “but I kept thinking, ‘What if I read the manuscript and it isn’t any good? How exactly does one tell the daughter of a president that the book doesn’t work?’”

Jenna began doing long interviews with Ana in Spanish and wrote five chapters over the course of three weeks. Connolly says that when she showed him what she had done, he was “blown away” by her ability to re-create the life of the young mother. Over Christmas break, Jenna gave the partial manuscript to her mother, a former teacher and librarian, who promptly circled all the passive verbs. (“Mom,” Jenna yelled, “it’s a first draft!”) Washington lawyer Robert Barnett, who specializes in securing book deals for Beltway VIPs, took her and the five chapters to meet publishers in New York. The editors at HarperCollins were so impressed that they offered her a reported $300,000 advance—not bad for a book for teens, and not bad considering that no one knew (or knows) if a book by a Bush would sell in a country that is, at the moment, anti-Bush. “In my first conversation with Jenna, I felt inspired just listening to her talk,” says Kate Jackson, the editor in chief of HarperCollins children’s books. “I saw that she was a very gifted writer, a natural talent. She had an innate sense of how to make the pacing of her book incredibly tight and intense, which is not what you usually see in a new author.”

When Jenna returned to her internship, she met with Ana at least four times a week, asking dozens of questions and then writing. “Day and night,” says Baxter, “sitting at her desk in front of her laptop, wearing these huge goofy headphones that would block out noise.”

“It was pure lunatic writing,” Jenna says. “Mia probably thought, ‘Oh, we’ll go to the beach on weekends, we’ll go hiking, we’ll go to a festival,’ and I’d say no and I’d write. I got inspired. I got inspired about getting out there and opening kids’ eyes about someone like Ana and talking with them about how they can help change things. I feel like kids want to make a difference, but they don’t know how. Or they don’t feel empowered. They don’t feel they can actually change the world, and I think they can.”

Although Jenna says she arranged for part of her advance to go to a fund to pay for Ana’s college education, she initially did not tell Ana who she was. She truly loved her anonymity during those months—“walking up and down the streets, not having people do double takes,” she says—and she didn’t want her fame to get in the way of her relationship with her subject. But she couldn’t stay anonymous forever. When she met Barbara in Argentina for a few days of vacation, the freewheeling local press got ahold of the news, and soon there were reports that Jenna and Barbara had been seen running nude down a hotel hallway, that Jenna had fallen in love with a young man in Argentina and was bringing him back to Washington to meet her parents, that U.S. embassy officials had “strongly suggested” that the twins leave the country because of security concerns. It wasn’t long before the U.S. media were repeating the same stories—“the Paris and Britney of the political world!” the New York Daily News called them—and late-night comedians were on the air with yet another round of jokes. Jon Stewart: “Just to repeat: Argentina, former safe haven for Nazi war criminals, is drawing the line at the Bush twins!”

“Lies, all lies,” Jenna tells me with a sigh. “There was no nudity, no running up and down hallways, no getting kicked out of the country—and no new boyfriend.”

On that last point, she is especially emphatic. Unbeknownst to most people, Jenna had been in a serious relationship for several years with Henry Hager, who was working in Karl Rove’s office when she met him during the 2004 campaign. Described by one columnist as “tall, dark and Republican,” Henry was first spotted with Jenna when he escorted her to one of the inaugural balls. He made news again after complaining that a spin class teacher at a Washington sports club was making anti-Bush jokes. Still, he’s known to have a sense of humor: One evening he persuaded the Bush family to watch a video of the black comedian Dave Chappelle impersonating the president.

When I’m with Jenna in July, word of the engagement has not yet leaked. When I ask her point-blank if she’s getting married, she says no. When I try to get her to give me some information about Henry, who is enrolled in graduate business school at the University of Virginia, she’s coy. When I ask, for instance, if he’s the son of a Virginia politician, she says, “I’m not even sure.”

But later in the conversation, she begins to open up, telling me Henry has passed what she says is her dad’s “boyfriend test.” (He was able to keep up with the president during a mountain bike ride but, no doubt to the president’s joy, was unable to get in front of him.) She says that she and Henry took a long camping trip together in 2006, driving from her parents’ hometown of Midland to Big Bend, where the owner of a bakery in Alpine, without knowing who they were, gave them a huge bag of doughnuts and brownies. (“Henry was shocked. He’s an East Coast boy. He couldn’t believe how friendly people were.”) From there they went to the Grand Canyon and on to Zion National Park, in Utah. “We hiked and hiked and hiked and read books at night,” she says. “On that trip, we reread our favorite books from school.”

“What did your dad say when you told him you and your boyfriend were going on a trip?”

“He said, ‘Do you have two tents?’”

“I assume that if Henry comes to visit you at the White House, he stays in his own room.”

“Oh, yeah.” She laughs. “Dad’s still the traditionalist, you know.”

The date and place of the wedding have yet to be disclosed, though another of Laura Bush’s biographers, Ronald Kessler, says he has been told it will be held in May at the ranch in Crawford. Meanwhile, Jenna will have her book tour to finish. She clearly likes being a writer: She’s signed a contract with HarperCollins to write another children’s book, this one with her mother, about a boy who does not like to read. (Presumably he does not grow up to be president.) Although Barbara’s personality is more like the first lady’s, Jenna and her mom are close because of their shared interest in teaching and reading. Jenna, who moved into the White House after her UNICEF internship came to an end last summer, says she and her mom love to get into bed and talk about the novels they’re reading. A recent favorite of Jenna’s is Daughter of Fortune, by Isabel Allende. “Allende’s great,” she says. “All of the books I read have strong women characters going out and conquering and becoming independent, and they don’t care about men.”

Jenna sleeps in what she says is “the White House kids’ bedroom,” just down the hall from her parents’ room. (John F. Kennedy Jr., LBJ’s daughters, and Chelsea Clinton all slept there.) When I ask her what it’s like to live in the White House, she gives me the kind of throwaway answer that’s almost worth a story in itself: “I feel like it’s filled with millions of ghosts. I get scared there sometimes. I’m not kidding. I have heard ghosts, I really have—ghosts singing opera. One night, opera noises came out of my fireplace. When I told my sister, she didn’t believe me, but the next week we were up late in that bedroom and we heard 1950’s piano music. People will think I’m crazy for saying that.”

When she’s with her father, she says, they don’t talk shop. She doesn’t read the papers or watch the news because she can’t bear to hear him criticized. “You know, when you really love somebody, especially your father, I mean . . .” She pauses, and her eyes fill with tears. “I see him as a father. I see him as the father who took us to soccer games. For me, he is a father who is so much fun. So, yeah, it’s hard to see. But, you know, you have to ignore it.”

I ask her if, in the waning days of his administration, the president is truly at ease, as he seems to be. She gives me a long look. “No,” she finally says, “not all the time. He acts like he’s at ease—or tries to act like it—but he’s not always.” She’s looking forward to January 2009, she adds, so that her parents can return to Texas and can “just relax. They really can’t relax right now.”

Does Jenna plan to return to Texas too? While she talks at length about how she misses Austin, she’s staying mum about where she and Henry will end up. As for writing, she says she’s not sure about that either. But she does say that regardless of what happens, she will keep teaching. “In our society, where pop culture rules the pages, no one is interested in somebody who teaches,” she says. “But it’s something I love.”

She’s serious. One afternoon before I leave Washington, I drive for the last time past Jenna’s school. I see her down the street at a small city park, where the kids are climbing around on a dilapidated playscape. She is just another young teacher, completely anonymous. A couple of downtrodden people sit on a bench, paper bags at their feet. On another bench is an elderly couple, the husband patting the wife’s back. Young men, apparently with no place to be, stand on a street corner, staring at traffic. No one looks her way.

I sit in my car across the street, unseen, and watch her for a few minutes. She smiles at her kids as they run back and forth, then starts laughing at something one of them says to her. Finally I hear her shout, “Come on, guys! Recess is over!” They line up and head back to school, Jenna leading the way. As they walk through the front door, she’s still smiling.