Goats probably matter a lot to more people in the world than Texans do, but in general Texans themselves don’t know or care much about goats. It is possible to consider this peculiar, in the light of a couple of facts. First, the state can be regarded as a northern outpost or petering-out of Latin American civilization, and Latins, whether at home along the Mediterranean or over here, are among the world’s goat experts par excellence. But all this lore boils down to for most Texans—including I fear most modern Texas Latins—is an occasional expensive encounter with cabrito and maybe a remembrance of the savor of the good stout fibrous goat cheese, pale in hue, that used to give enchiladas and chiles rellenos their whang, until even Mexican cooks went down the primrose lane with Kraft.

Furthermore we Texans have within our boundaries, or had until just lately, one of the world’s great concentrations of goats: the big herds of long-haired Angoras that thrived on the live oak and other hardwood scrub of the Edwards Plateau and similar limestone regions. But despite their numbers—over four million strong at their peak in the sixties—I suppose the Angoras were never a big part of most Texans’ consciousness, restricted as they were to some fairly lonesome parts of the state and usually hidden from the eyes of motorists by the brush in which they browsed. More than once when traveling with city friends, I have heard them referred to as sheep. The herds shrank hugely (most were shipped to Mexico for meat) when mohair fell out of fashion and the market collapsed. And though mohair’s vogue and its price have lately come back strong, ranchers’ caution about further fluctuation as well as other factors such as predation—chiefly by coyotes and dogs and hybrids thereof—have kept hair goats from regaining their old status. Much of the world’s mohair is now produced by South Africa, and when you see goats on the Plateau and roundabout, they’re as likely to be of the tough, unhairy, common sort known as “Spanish.”

Both Angora and Spanish goats control brush and furnish kids for barbecue, and both are the subjects of a considerable body of ranchers’ folklore involving mainly their ability to get out of where you put them and into places where they’re not supposed to be, such as grainfields and neighbors’ pastures and highway median strips. If you want an adequate goat fence, one story goes, you build it as tight as you can with closed-spaced posts and lots of upright stays, filling all dips in the ground beneath the net wire with rocks or stumps or something; then you wait for a big rain and if the fence holds water it will hold your goats. Another tale describes a scientific experiment conducted at A&M wherein three goats were stuffed into a steel drum that was then welded shut. When it was opened a week later, one goat was dead, another had screwworms, and the third one was missing.

When we used to keep a good-sized herd of Spanish goats here on our place, a few of each year’s crop of weanling kids, newly independent and capable of squeezing through holes impassable to their parents, would form a teenage gang that ravaged the neighborhood. Since they usually returned and their isn’t too much to ravage in these rocky cedar hills, problems resulted only when they tried to come back home through a part of the fence that had no holes, or when they got far enough afield to discover somebody’s yard shrubbery or vegetable garden. The resultant telephone calls—beginning most often with “Are you missing any goats?”—were not invariably friendly.

A generation or so ago in harder but more easygoing times, goats were known and taken for granted by a good many more Texans, and for that matter Americans, than know anything about them today. They existed even in cities, sheltered by crusty codgers in backyard sheds and sometimes tethered during the day in vacant lots or out among roadside weeds. Scrub milk nannies for the most part, with an occasional aromatic billy kept for propagation, they soothed many an aging or unquiet stomach with the rich liquid from their udders, furnished roly-poly manure for garden compost and kids for delicate meat, gave jesters a focus for worn boffo humor concerning tin cans and old inner tubes and grateful tumblebugs, and developed evil tempers under the teasing of small boys, including me. Without ever being what you might call chic or even reputable, they hung on.

But prosperity is even harder on goats than it is on human picturesqueness, and in the unreal, increasingly homogenous glitter-island of time that urban Americans currently inhabit, there is not much place for subsistence livestock, which is what goats fundamentally are. Public opinion and the public nuisance laws that reflect it have turned against them and other such creatures, and you usually have to go out beyond a city’s limits to its unzoned, often unincorporated fringes to find any goats at all, and not many are even there. Milk comes less arduously, though not cheaper, in cartons, and there has been among us a dwindling of stubborn country-bred old folks who cling to subsistence ways. If city vegetable gardening, based on poison-fear and anger at market prices and quality, is on the boom these days, city goat keeping has not been following suit.

Father away from cities, though, goats are in pretty good shape, and I’m not talking about big ranch herds. How much of the new population trend away from metropolitan centers, confirmed by the Census Bureau, represents flight to a less hectic but still supermarket-centered existence in small towns or urban “developments,” and how much consists of neo-homesteaders moving whole or part hog back to the land to live and subsist, I have no way of knowing. But in a time like ours when many view the urban future quite dimly, there are notable numbers of these latter searching out their destined two or ten or twenty or more acres, building a house or refurbishing an old one, laying out gardens and orchards, learning to grind wheat and corn for bread and maybe to ferment their own wine, training and preparing for tough times. Some have the cash to pay for all this out of pocket; others manage by commuting back to good jobs in the cities they have left, or by other activity.

As often as not their plans include livestock, preferably in small numbers and not too daunting in size. If they have in mind producing their own milk and butter and cheese, goats are a natural choice. Hence in the past few years there has been a solid little boom on the breading and sale of pedigreed dairy goats and a rocketing of their value. Breeders of good reputation with some show champions in their herds are asking and getting up to $300 to $400 for four-month-old weaned doe kids (“doe” and “buck” in this more genteel goat world having supplanted the old vacant-lot terms “nanny” and “billy”). Americans like to go first class, and these goats definitely have chic, at least in given circles.

If they are willing to pay as much as a first-rate milk cow would cost for a young beast that won’t be so productive for another year or so, the clear inference is that they most specifically want a goat. It was not always so in rural America. The traditional American family farm, the sort of frontier holding people staked out for themselves until the frontier reached country too dry to sustain traditional farm life, had little use for goats but relied instead on cows, of which the classic types were the big-eyed, sweet-breathed Jerseys and Guernseys and Ayrshires beloved of children’s-book illustrators.

There were some reasons for this. For one thing, most of those farmers’ ancestry traced back to the British lowlands and North Europe where cow’s milk ruled. Another reason was great big families—you need a fair group of people and couple of pigs besides to consume the three daily gallons or so that a good milk cow can give. And still another was the prime land that characterizes—or used to, before old-style agriculture chewed the topsoil from so much of it—farms in the eastern United States. For the milk cow is a good land-animal, faring and yielding but poorly in deserts and semi-deserts and arid mountains and the earth’s other reaches of marginal and submarginal soil, whether shaped by climate or man’s abuse of power or both.

Those reaches are the true stomping grounds of the goat, which can climb anywhere and thrive on skimpy forage in places that would starve a cow or a sheep. The names of the best-known breeds mirror such origins—Toggenburg and Saanen (both Swiss to start with), Alpine, Murcian (named after an Iberian province and the rootstock of most of the hardy “Spanish” goats of Mexico and South Texas), Nubian, even Angora for that matter. The Scottish Highlands cherished goats, and so did Norway, the vast high arid places of Asia, the rocky parts of Ireland, and all lands along the Mediterranean after the ancients had worn them out.

A well-established slander, which still crops up in forums like the United Nations, holds goats responsible for much of the ecological devastation in such places. Goat people resent this aloud or in print, including such luminaries as the late Scottish expert David Mackenzie, whose wise and whimsical Goat Husbandry is a sort of Bible for the whole clan. There is no question that goats out of control can do big damage, as they have on many small islands without predators, where ships from maritime nations turned loose breeding stock two hundred or more years ago to furnish meat for future voyages—R. Crusoe and his real-life prototype Alexander Selkirk having been beneficiaries of that practice. But in an area like the Mediterranean basin, for instance, the indictment is flimsy. Man with his reckless hillside farming, his vast herds of any and all species of livestock, his axes and saws and ever-waxing numbers—man is the one who did it. And if goats are still around consolidating the damage because they are the only domesticated beasts that can now survive in some parts of the region, that is not the goats’ fault.

Goats also spread long ago, though never quickly, to many richer regions. The reasons were sociological, not unlike those that sprinkled scrub nannies about the cities of my youth. If you have a held-down peasantry shut off from the ownership of good land and restricted in terms of livestock to creatures that can be kept in a dooryard or pastured alongside roads or on moors and other waste places, you have a readymade body of goat enthusiasts. Association with such owners did little for goats’ social standing, of course, and in most North European countries they were and remain somewhat raunchy figures of fun. Which makes it all the more remarkable that upper-class Britishers of the past century or so, with the pleasant unmercenary thrust toward investigation and discovery and perfecting things that so many of that ilk have possessed, have had much to do with firming up the main breeds of dairy goats and improving them into the beautifully efficient milk producers they are today. And in this country, people far different from the crusty backyard codgers of yesteryear have carried on the refinement process.

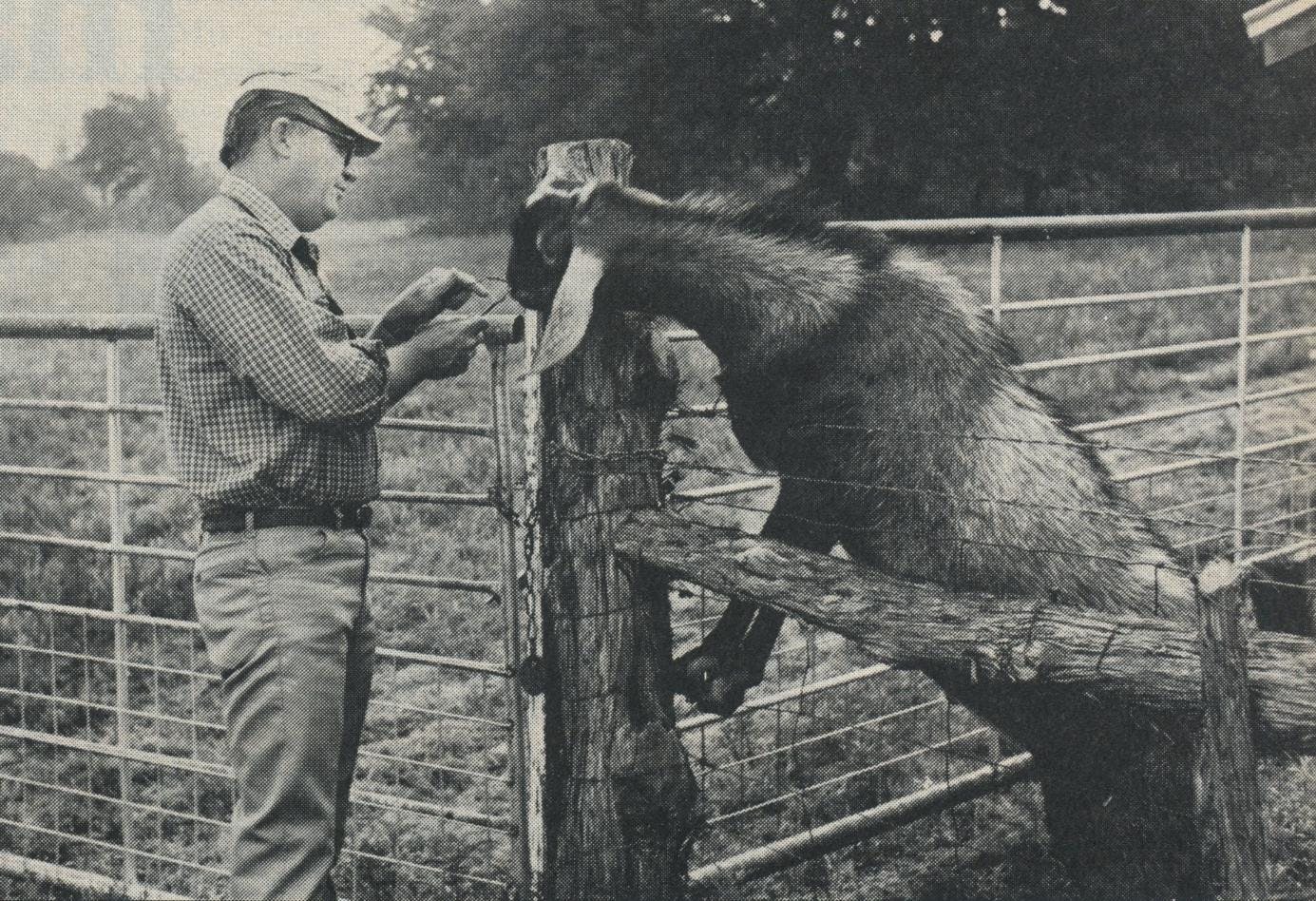

If the neo-homesteaders who inherit the results continue to increase or even just to survive at their present level, it seems likely that goats will keep on having a place among us too. It is not just small holdings and small families that make them popular among such people, nor is it just a doe’s daily gallon or so of good sweet milk (far different from the strong stuff many of us remember getting in our morning café con leche during sojourns in rural Mexico, where billies run free with the herds and the stink gets into everyone and everything). As much as anything, it is the potent charm that nearly all goats have, and the variations in personality that are as sharp as in dogs and cats. They play among themselves, and to see a file of them dancing and bucking sideways in sheer pleasure as they head for pasture in the morning is to know why our words “caper” and “caprice” come from the Latin for goat. They play with people, too, and nuzzle and demand and talk, and most people who know them talk back. Call it sentimentality if you want, but I have known some very leathery types, with no soft feelings otherwise discernible, who habitually conversed with goats. Goats are gentle beings by nature and for every one that butts people there is a corresponding human, nearly always small and male, who helped to develop the habit. They deserve to survive, and people will survive a bit more richly if they have some goats around.

I will confess that the milk sort are a lot of trouble unless your life jibes well with their ways. Twice a day with feed and bucket you have to bethere, and not be in Austin or Fort Worth or a few miles away sipping beer and swapping goat folklore with friends. Your failure to show up when that established, precise, magical hour for milking rolls around will mean that when you do show up you’ll have to face a very disgruntled and loud-mouthed set of goats, and if you do it often their disgust will evince itself in very measly production. Here at the place, for such reasons, we reluctantly got rid of our best milk goats last year and at present have only one old pet Nubian, now dry, and a handful of Spanish goats that come to the corral at night for a handful of corn and protection against coyotes and roving dogs. Even these half-wild specimens have stout individualities and names, and the ancestry of any kid in the bunch from Doorbell down through William and Creampuff and Pearlie May or whoever. Which makes for problems at barbecue time.

As for the hand-raised lactating pets we got rid of last year, it turns out we didn’t at all. When driving past the ranch where they live now, as pampered as ever, we find ourselves dropping in to see them and to be greeted with recognition and old affection. I never specifically visited a cow in my life, or even a horse or a dog that I remember. But I visit goats.