COVERING THE DALLAS COWBOYS back in the sixties, I sensed that something special was evolving, but I never dreamed that I was witnessing the creation of modern pro football. Forty years later, things are clear. Conception occurred when Clint Murchison, Jr., hired a CBS television producer and former general manager of the Los Angeles Rams named Tex Schramm and gave him the job of organizing his new National Football League franchise in Dallas. While I was busy writing trivia about multiple offenses and flex defenses for the Dallas Times Herald and later the Dallas Morning News, Tex was merging pro football with television and recasting the image of the NFL to the point where pro football would shove aside baseball as the national pastime. What do they say about forests and trees?

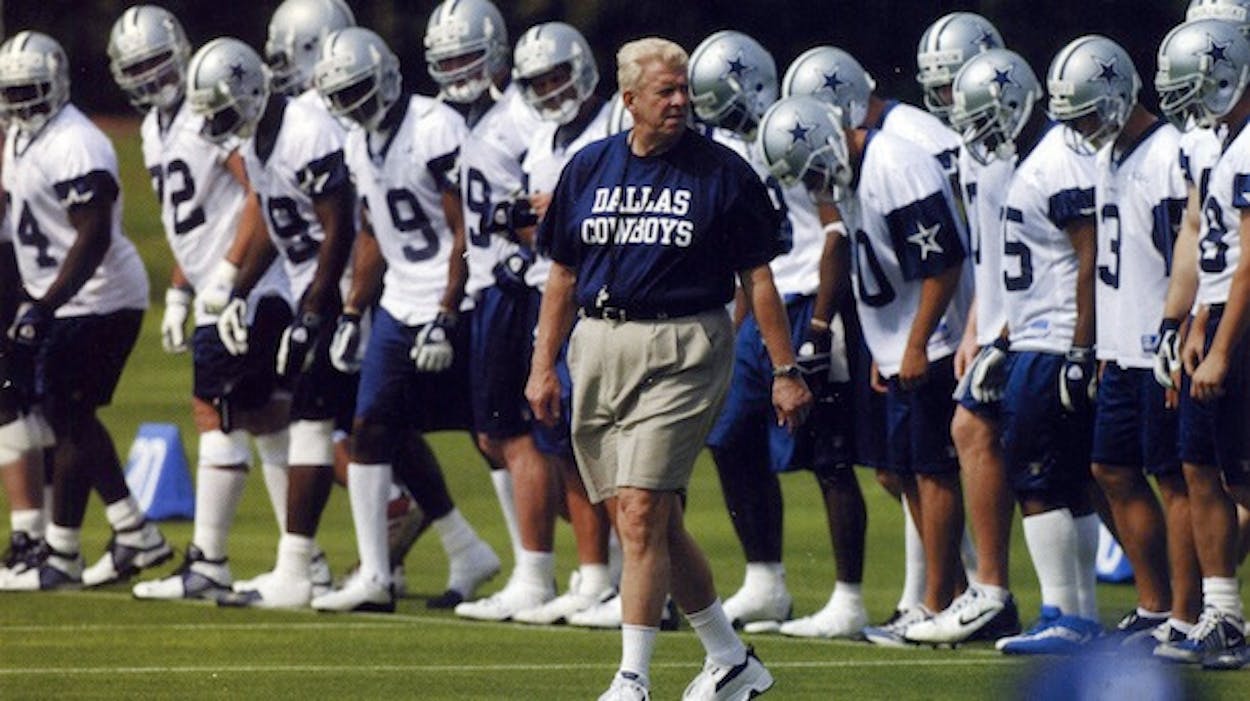

When Tex died, in mid-July, just days before the forty-fourth edition of the Cowboys reported to training camp, it was the perfect juxtaposition of the classic and the retro-modern. Tex exits to heaven and Bill Parcells puts the Cowboys through hell. Tex would have appreciated the production, especially since he got top billing. Though Parcells was still earning his spurs as an assistant college coach when the Cowboys started winning Super Bowls, he represents a throwback to the kind of smash-mouth football that Tex loved. So let the games begin.

There was another side of Tex, however, one that was warm, generous, human, and even a little silly. I’ll tell you a story I’ve never told anyone, except a few dear friends. Back in the days when Tex was doing all those amazing things for the Cowboys and the NFL, a couple of Dallas sportswriters named Shrake and Cartwright dropped uninvited by his North Dallas home late one night. Shrake was dressed as Batman, Cartwright as Robin. Why we chose that particular wardrobe is lost in the fog of history. The point is, instead of calling the cops, as almost any other major sports figure would surely have done, Tex and his wife, Marty, seemed delighted by the intrusion. They invited us in, broke out a bottle of J&B, and we chatted until nearly midnight. Over the years, I’d nearly forgotten that evening, but Tex hadn’t. Last December, a day or two after Marty died, Bud Shrake called Tex to express condolences, and in the course of their conversation, Tex recalled that long-ago visit by the Dynamic Duo. “It was an unforgettable sight,” he chuckled.

Tex’s zest for life vanished after Marty died. He did rally for a few public appearances, once when his biography, written by former Morning News columnist Bob St. John, was published, and a second time, in April, when he visited Texas Stadium for the first time since submitting his resignation to Jerry Jones fourteen years ago. The occasion was Jones’s belated announcement that sometime during the 2003 season Tex Schramm’s name would be added to the Cowboys Ring of Honor, the twelfth in a list of legends that includes Tom Landry, Bob Lilly, and Don Meredith. Considering that Tex created the Ring of Honor in 1976 and that he has been a member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame for twelve years, the gesture could be viewed as too little, too late. In Tex’s eyes, however, nothing associated with the history of the Cowboys was inconsequential. Sports columnist Frank Luksa reported that the 82-year-old Tex discarded his walking stick and “literally rose to the occasion . . . in stubborn rebellion against infirmity. [He] straightened his bent body as best he could and made his way to the stage to bask in forthcoming attention.”

The honor will have to be bestowed posthumously. That wouldn’t have bothered Tex. One season concludes, another begins; one generation dies, another is born. He knew that this year’s results are more important than past glory.

THE COWBOYS HAVE HAD ONLY two legitimate NFL head coaches, Tom Landry and Jimmy Johnson, and Jones fired them both. If metallic blue and silver runs through your veins, you can hope with me that this time Jones has gotten it right. I have no doubt that Parcells is the real thing. The man is an old-fashioned ass-kicker—tough, demanding, bullying, manipulative, abrasive, intimidating, and stubborn. Whatever else, this will be an interesting season.

Hearing tales of Parcells on the practice field, this enormous, pear-shaped ball of napalm, racing fifty yards to grab a 350-pound lineman by the pads and shake the lad until he rattles, you realize that he is a heart attack waiting to happen. A bad heart was the primary reason Parcells retired in 1991, after the Giants’ second Super Bowl victory. Only 49, he faced bypass surgery and a future unknown. He returned to pro football two years later, this time with the challenge of rescuing the lowly New England Patriots. In 1996 he took them to the Super Bowl, then jumped to the New York Jets with a year left on his contract. In 1999 he expected to take the Jets to the Super Bowl, which would have made history: No coach has taken three different teams to the Super Bowl. Parcells was a bundle of raw nerves that final season, so pumped up that he had to take medication before each opening kickoff to control his arrhythmia. Unfortunately, injuries wrecked the Jets, and Parcells retired a second time, so close and yet so far away from football immortality.

When Cowboys fans heard in January 2003 that Parcells was coming to the rescue, many assumed their worries were over. I wasn’t so sure. Having watched the Cowboys stumble through three coaching changes after Landry and Johnson and three consecutive 5-11 seasons, I was surprised that Parcells had agreed to coach for a control freak like Jerry Jones. After all, he had spent a good part of his career complaining about front-office types who can’t resist meddling in football affairs. “If they’re going to ask you to cook the meal,” he has said, “they ought to let you buy the groceries.” Sure, Parcells was the ideal coach to resurrect the Cowboys. But why would he want to?

I found the answer by reading Parcells’ autobiography, published at the conclusion of that wretched 1999 season and ironically titled The Final Season: My Last Year as Head Coach in the NFL. Parcells compares himself to a fighter who must keep proving himself. “That’s my personality,” he writes. “That’s what keeps me going. . . . I still [want] to climb into the ring, at least one more time.” Though his book is mostly about absolutes, Parcells vacillates wildly on what he will do with the rest of his life. He’ll never coach again, that’s for sure. No, he has to coach again. He can walk away from football and never look back. No, he’d rather die first. He doesn’t want to be carried off the field, boots first. But, as he has said on several occasions, “This game is going to kill me yet.”

FEAR AND INTIMIDATION ARE THE tools Parcells uses for motivation. It shows in the results and in the published comments of his former players. Almost all of them respect him, but hardly anyone loves or even likes the bastard. Bob Kratch, an offensive lineman who played for Parcells with the Giants and the Patriots, told Sports Illustrated in 1997 that Parcells was “sometimes the nastiest person you ever met.” Phil Simms, the Giants’ All-Pro quarterback under Parcells, spoke of his great admiration for the coach but added, “I didn’t enjoy one minute of it.” Another former Giants player said, “If Parcells was named king of the world on Sunday, he’d be unhappy by Tuesday.” Parcells demands loyalty but doesn’t always give it. In his biography, Parcells, writer Bill Gutman reports that Parcells left New England in such a hurry that he didn’t bother to say good-bye to his players. Star quarterback Drew Bledsoe told Gutman, “From the get-go, Bill has been about Bill. . . . That’s the way he is.”

Parcells’ tyrannical reputation preceded him in Dallas—as he had intended. Before many of the current Cowboys met their new coach, a memorandum appeared on the locker room bulletin board. In the style of a manifesto that a military commandant might post on the city hall door of a village he has conquered, it laid out rules and regulations. Players’ cars not parked properly would be towed. Cell phones would be turned off before entering the locker room. No food in the locker room, training room, or weight room. The memo said nothing about dominoes or boom boxes, but everyone got the message. In short order, the Cowboys locker room was as neat, quiet, and orderly as a monk’s cell.

Then signs began to appear throughout the team’s Valley Ranch training facilities, plainly stating Parcells-isms: “Be on time. Pay attention. Practice and play hard.” “Think turnover!” “Three fights every day: (A) Division from within. (B) Your competition. (C) Public perception.” “A few poor character guys ruin even the best of teams.”

Parcells personally supervised the team’s off-season weight-and-conditioning program, something that even the meticulous Jimmy Johnson didn’t always do. He gave each player a maximum weight for training camp; two offensive linemen needed to lose thirty pounds. Players who reported to camp overweight would be fined the league maximum, which last year was $235 per pound, per day. Two All-Pros, Larry Allen and La’Roi Glover, committed to a conditioning plan that would get them in the best shape of their careers. Antonio Bryant, a talented receiver who stood out last year mostly for his big mouth and bad attitude, was suddenly following Parcells like a puppy panting for approval. “If there’s going to be a fat guy on this team,” Parcells said, “it’s going to be me.”

Before the start of minicamps, Parcells signed several free agents that had played for him on other teams—fullback Richie Anderson, receiver Terry Glenn, and tackle Ryan Young. They are what he calls “hold the fort” players, guys who can fill holes immediately while imparting the party line. Anderson, a former Jet, quickly became the Cowboys’ new vocal leader. “It’s important for me to have guys like that—smart, dedicated, productive football players who know what their job is,” Parcells told the Morning News. Young warned the Cowboys that once training camp started, they should expect the worst. “While some coaches might let up after a while,” he said, “Coach Parcells just keeps coming at you and pounding you until it’s done his way.”

Unpredictability is one of Parcells’ strong suits. He has been known to walk off a practice field three days before a game, which is his way of telling his team, “Okay, you don’t want to do it my way. You girls coach yourselves.” As he explained in The Final Season, some days he’s hearts and roses; other days he drips acid. Some weeks he tells his coaches to ease off. Some weeks he tells them, “No buddy-buddy, no chitchat with the players. Be all business. Be good teachers, but don’t be cordial. Don’t be friendly. I don’t want friendly.”

The Cowboys quickly learned that Parcells was as tough as his reputation. Mental lapses, physical shortcomings, and stupidity resulted in instant and terrible punishment. If a player failed to know what play had been called—even if the player wasn’t in the huddle—the entire unit, offense or defense, was forced to run 150 yards across a practice field and up an incline. Parcells believes in the therapeutic value of “gassers”: four wind sprints across the field and back in no more than 38 seconds. Gassers are often followed by a few “up and downs”: running in place, knees high, then belly-flopping to the ground. In the days before players lifted weights, legendary coach Vince Lombardi used “up and downs” to develop players’ arms and chest muscles. Parcells uses them to develop character. Examples abound of how he also uses sarcasm and insults. “Any day now, ladies,” he yells as they hustle from drill to drill. When Glenn was a rookie with New England and reporters asked the coach about his injury status, Parcells replied that “she” was doing as well as could be expected. If a player passes out from the intensity of a workout, he’s liable to wake up to find he’s been cut. A player who throws up from exhaustion might be warned, “Throw up on your own time.”

“If you’re sensitive,” he has told generations of players, “you will have a hard time with me.”

NEVERTHELESS, PARCELLS CAME TO DALLAS sensitive to the feelings of an owner who, at least since Jimmy Johnson left town, has made all the decisions. At the introductory press conference where Jones announced that Parcells had agreed to a $17 million four-year contract, Parcells let Jones do most of the talking. But it was clear that the two men had agreed to defer to each other. The clock is running: Parcells is 62, Jones is 60, and both know that this partnership is probably their last chance at a Super Bowl.

Parcells hunkered down, keeping a low profile and making himself scarce. He didn’t want the media to get the notion that he was there to control and replace Jones. Asked if it bothered him when Jones issued pronouncements about personnel, Parcells replied, “I think we’re going to be philosophically compatible with it. We’ve had many exchanges about things of that nature since I’ve been with the Cowboys. I think it will work out okay.” Behind the scenes, Parcells assembled his staff (something no Cowboys coach had been allowed to do since Johnson), signed free agents of his choosing, and got ready for the draft. He was acutely aware that the operation of a modern pro football team is largely about perception. When he told the media that from then on the organization would speak with “one voice,” he implied two-part harmony.

Draft day, in April, was the first public show of this new division of power. Bill advised and Jerry made the calls. After the Cowboys had completed their first- and second-round selections, Jones spoke with reporters while Parcells stayed behind in the war room. Jones compared the team’s top pick, Kansas State cornerback Terence Newman, to Deion Sanders, maybe the best cornerback of all time. Late that night, after the teams had finished for the day, Parcells carefully contradicted his boss to an Associated Press reporter: “I think that would be a little premature to compare him to one of the better players that’s played in the league. In fact, that would be very premature.” Jones wanted to fly Newman to Dallas that night in his private jet, but Parcells vetoed the idea. “I don’t want to separate the first-round draft choice,” he said. “I don’t care if he was drafted first or three-hundredth. He’s part of the team now.”

In Parcells’ caste system, rookies are two levels below untouchables, regardless of how high they are drafted or how much they’re paid. At the first minicamp, Newman was singled out as the player responsible for fetching cups of water for the head coach during breaks. Glenn, the seventh player taken in the 1996 draft, also got to fetch water for Parcells. “Coach Parcells doesn’t want anyone thinking they are bigger than the team,” he explained to the Morning News. Nor were rookies permitted to display the famous Cowboys star on their helmets during minicamps or training camp. “They’re just numbers right now,” Parcells said. “The stars have to be earned.”

What went almost unnoticed was that in the days leading up to training camp, Jones redirected his energy to marketing, scouting, and masterminding negotiations for a new stadium, areas in which he excels. For the first time in his fourteen years as Cowboys boss, Jones began to resemble—dare I say it?—Tex Schramm. Only without the sense of humor.

TEX LOVED TRAINING CAMP. IT gave him time to think of bigger, better, newer, and flashier ways to market his product or gain a jump on the competition. In the summers between 1962 and 1967, I saw and talked to Tex daily but never imagined all the amazing stuff racing through his brain. He didn’t look particularly busy, standing on the sidelines of a practice field in Forest Grove, Oregon, or Marquette, Michigan, or Thousand Oaks, California, or dealing with the flow of incoming and outgoing players. When the impish Murchison sent a ringer named Rufus “Roughhouse” Paige to Cowboys camp with a signed contract, Tex took it in stride. He put Roughhouse on an airplane and sent him to Murchison’s private island in the Bahamas.

Most evenings, Tex took a bunch of us to a fancy restaurant, where we drank and argued about some arcane aspect of football until the early morning hours. Tex loved to argue and drink J&B. He was opinionated, stubborn, hot-tempered, and passionate about football, and he knew more about the subject than any man living. He read every word we wrote and wasn’t shy about hammering us when he disagreed. “What’s ‘autocratic’ mean?” he asked me one morning as we were leaving the dining hall. I’d written the previous day that Tex was the most autocratic general manager in football. He followed me to my training camp dorm room, where I read him the dictionary definition of an autocrat: “1. A ruler having absolute or unrestricted power; despot. 2. Any arrogant or domineering person.” Tex nodded as he considered the words. “I can live with that,” he decided.

Maturity and the perspective of time allow me to understand today what I saw but didn’t fully comprehend in the sixties. I remember, for example, standing in the rear compartment of a Cowboys charter flight, returning from California. Tex was huddled with Landry, chief scout Gil Brandt, and two or three assistant coaches, and they were conferring with a small, dark man named Salam Qureishi who worked for IBM. At that exact moment, Tex was perfecting and computerizing the player draft, something everyone in the league takes for granted now but a nascent science back then. The Rams of the late forties were the first team to put resources into a scouting system, and Tex had seen its value up close.

Tex also took some gambles that paid off big. In 1964, for example, the Cowboys drafted two of their greatest players in late rounds. They got an Olympic star named Bob Hayes in the seventh round, because other teams tended to ignore players from obscure schools like Florida A&M University. And they grabbed a quarterback named Roger Staubach in the tenth round, even though he had a year of eligibility left at Navy plus a four-year military commitment.

Manipulating for advantage kept Tex young. Sometimes his manipulating helped the Cowboys; sometimes it helped the league. In his mind it was the same thing. Tex was instrumental in bringing about the NFL’s first big network television contract. At CBS, he had produced the first televised Winter Olympics, an idea he had conceived and sold to a dubious network that never dreamed it was possible to cover such a multifaceted event or that sports alien to most Americans would prove so popular. If Americans would sit still for skating and downhill racing, Tex knew they’d die to watch pro football. The billions that poured in from TV were shared among the teams; revenue sharing and the common draft allowed teams to compete equally, regardless of market size, an advantage that baseball has yet to recognize.

Tex hated anything that wasn’t NFL, and that included the rival AFL. But in 1966, when the two leagues were fighting a war that nobody could win, Tex telephoned Kansas City Chiefs owner Lamar Hunt—think Nixon going to China—and the two of them met and began negotiating football’s historic merger. The first benefit of the proposed merger was the 1967 Super Bowl, matching the top teams from each league. Tex brought sexy cheerleaders who were professional dancers to the NFL too and instant replay and the wild-card playoff system. He didn’t coin the term “America’s Team,” but he made it his own, to the envy and distress of everyone else in the league. He was a fierce and unrelenting competitor. Who but Tex would have dared protest when record-setting kicker Tom Dempsey, born with a deformed right foot, was permitted to wear a special shoe designed to resemble a driver? I can’t remember if Tex won the protest, but I do remember sitting next to him in the press box in the closing seconds of a Cowboys-Eagles game. Dempsey was the Philadelphia kicker that year, and as he lined up what could be the game-winning field goal, I heard Tex mutter under his breath, “Hook it, loser.” And Dempsey hooked it.

In some ways, it’s a different game today. Because of free agency and the salary cap, a team can go from also-ran to Super Bowl champ in a year or two. In Tex’s day, a general manager could assemble talent sufficient to win a Super Bowl and retain it until the players wore out. But Tex claimed that no matter how things change, the smart teams always win. It was true then and it’s true now. Teams like the Raiders, 49ers, Giants, Packers, and Broncos were contenders ten years ago and are still contenders. If Jerry Jones wants to know how to win, he should ask himself what Tex Schramm would do. Forget about calling plays and start thinking of ways to outsmart the opposition.

DON’T EXPECT PARCELLS TO BE a public figure in Dallas. He has always been a loner who, in all his years in football, has made few close friends. In recent years his circle has narrowed even further. The co-author of his autobiography, Will McDonough, died just before Parcells took the Cowboys job, and his agent and friend Robert Fraley died in the 1999 plane crash that took the life of golfer Payne Stewart. After 39 years of marriage, his wife, Judy, divorced him. Parcells lives alone in an apartment at Las Colinas, a short drive from the Cowboys’ Valley Ranch complex. He has almost no social life, except an occasional round of golf or a trip to the racetrack. Most days, he arrives at his office early and stays late. Behind his desk is a photograph of him and Landry, taken before a game at Texas Stadium in the mid-eighties, when Parcells coached the Giants. Above the desk is a sign that advises “Just Coach the Team.” Outside influences must be ignored.

In a profile of Parcells, published in June in the Morning News, writer Juliet Macur reported that on Mother’s Day, Parcells played golf by himself at the Cowboys Golf Club in Grapevine. “It was early, the course empty,” she wrote. “He played ten holes, often hitting two balls from the tee, killing time until he needed to be at Valley Ranch.”

There are no sure things in the NFL, though Parcells comes close. The Cowboys will eventually win and win big, but it’s not going to happen this year or next. This year’s edition is good enough to finish 8-8, three games better than last year. But then the Cowboys could have won three more games last year if they hadn’t made so many mistakes, committed so many penalties, coughed up so many turnovers, or missed so many easy field goals. These are failings that Parcells can fix. He will turn a bad team into an average team, but he knows what a good team looks like, and he hasn’t seen one yet in Dallas. Tearing the club apart and starting over isn’t an option. He has to patch and fill as opportunity presents itself.

Historically, Parcells’ teams win with solid defense and by running the ball and controlling the clock. This year’s team will have to win with defense; otherwise forget about it. And they must do so without a good pass rusher. The offense hasn’t a clue how to replace Emmitt Smith, the most productive running back in NFL history. Nor is there a proven quarterback. Parcells showed no interest in any of the free-agent quarterbacks available last spring. Barring an unexpected move, he has to go with either Quincy Carter, who was benched last year after throwing four interceptions in a loss to Arizona, or Chad Hutchinson, the former baseball player who, after replacing Carter, was sacked 34 times and fumbled 12 times.

Notoriously hard on quarterbacks, Parcells berates and abuses them on the theory that it prepares them for the licks they’ll take from an opponent. But he can bring out the best in a quarterback too; he’s a master at taking underachievers and motivating them to play to their potential. If he can do that with tackle Flozell Adams, pass protection will improve greatly. Parcells is searching for what he calls “foxhole guys,” the kind you want when you go to war. “I’m looking for guys who are willing to do whatever it takes to win all the time,” he has said. “You don’t get medals for trying. You get medals for achievement.”

It took Parcells four years to transform the Giants from losers to Super Bowl champs and another four years to get the Patriots to the Big Dance. Four years is what he has in Dallas. My guess is he’ll get to another Super Bowl—or die trying.

- More About:

- Sports