This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

I’d made the mistake, the evening before, of mentioning to my younger daughter that I’d heard the crappie and sand bass were running in the Brazos. Therefore that Saturday morning, a clear and soft and lovely one of the sort our Texas Februarys sometimes offer in promise of coming spring, filled with the tentative piping of wrens and redbirds, I managed to get in only about an hour and a half’s work in my office at the rear of the barn before she showed up there, a certain mulish set to her jaw indicating she had a goal in mind and expected some opposition.

I said I needed to stay awhile longer at the typewriter and afterward had to go patch a piece of net-wire boundary fence in the southeast pasture, shredded by a neighbor’s horned bull while wrangling across it with my own angus herd sire. She reminded me that the winter before we had missed the best crappie day in local memory because I’d had something else to do, one somewhat greedy fellow whom we knew having brought home 83 in a tow sack. She was fifteen, and it struck me sometimes, though not to the point of neurosis, that maybe she deserved to have been born to a younger, less preoccupied father. In answer to what she said I raised some other negative points but without any great conviction, for I was arguing less against her than against a very strong part of myself that wanted badly to go fishing too.

The trouble was that those two or three weeks of late winter when the crappie and the sandies move up the Brazos out of the Whitney reservoir in preparation for spawning can provide some of the most pleasant angling of the year in our region on the fringes of dry West Texas, where creeks and rivers flow tricklingly if at all during the warmer parts of a normal year. Even when low, of course, the good ones have holes and pools with fair numbers of black bass and bream and catfish, and I’ve been fishing them all my life with enjoyment. But it’s not the same flavor of enjoyment that a hard-flowing stream can give, and those of us who have acquired—usually elsewhere—a penchant for live waters indulge it, if we’ve got the time and money, on trips to the Mountain States, and look forward with special feeling to those times when our local waters choose to tumble and roll and our fish change their ways in accordance.

This section of the Brazos, my own personal river of rivers if only because I’ve known it and used it for so long, is a sleepy catfishing stream most of the time, a place to go at night with friends and sit beneath great oaks and pecans, talking and drinking beer or coffee, watching a fire burn low while barred owls and hoot owls brag across the bottomlands, getting up occasionally to go out with a flashlight and check the baited throwlines and trotlines that have been set. Its winter run of sand bass and crappie is dependable only when there’s been plenty of rain and the upstream impoundments at Granbury and Possum Kingdom are releasing a good flow of water to make riffles and rapids run full and strong, an avenue up which the fish swim in their hundreds of thousands. But it is pleasant when it does take place.

I’ve never been very happy fishing in crowds, and after word of a run of fish has seeped around our county the accessible areas along the river can be pretty heavily populated, especially on weekends in good weather and even more especially at the exact riverbank locations most worth trying. So that morning when without much resistance I had let Younger Daughter argue me down, I got the canoe out, hosed off its accumulation of old mud dauber nests and barn dust, and lashed it atop the cattle frame on the pickup. If needed, it would let us cross over to an opposite, unpeopled shore or drop downriver to some other good place with no one at all in sight.

After that had been done and after we had rooted about the house and outbuildings in search of the nooks where bits of requisite tackle had hidden themselves during a winter’s disuse, the morning was gone and so was the promise of spring. A plains norther had blown in, in northers’ sudden fashion, and the pretty day had turned raw. By the time we’d wolfed down lunch and driven out to the Brazos, heavy clouds were scudding southeastward and there was a thin misty spit of rain. This unpleasantness did have at least one bright side, though. When we’d paid our dollar entrance fee to a farmer and had parked on high firm ground above the river, we looked down at a gravel beach beside some rapids and the head of a deep long pool, a prime spot, and saw only one stocky figure there, casting toward the carved gray limestone cliffs that formed the other bank. There would be no point in using the canoe unless more people showed up, and that seemed unlikely with the sky’s grimness and the cold probing wind, which was shoving upriver in such gusts that, with a twinge of the usual shame, I decided to use a spinning rig.

Like many others who’ve known stream trout at some time in their lives, I derive about twice as much irrational satisfaction from taking fish on fly tackle as I do from alternative methods. I even keep a few streamers intended for the crappie and white bass run, some of them bead-headed and most a bit gaudy in aspect. One that has served well on occasion, to the point of disgruntling nearby plug and minnow hurlers, is a personal pattern called the Old English Sheep Dog that has a tinsel chenille body, a sparse crimson throat hackle, and a wing formed of long white neck hairs from the amiable friend for whom the concoction is named, who placidly snores and snuffles close by my chair on fly-tying evenings in winter and brooks without demur an occasional snip of the scissors in his coat. Hooks in sizes four and six seem usually to be about right, and I suppose a sinking or sink-tip line would be best for presentation if you keep a full array of such items with you, which I usually don’t.

But such is the corruption engendered by dwelling in an area full of worm-stick wielders and trotline types, where fly-fishing is still widely viewed as effete and there are no salmonids to give it full meaning, that increasingly these days I find myself switching to other tackle when conditions seem to say to. And I knew now that trying to roll a six-weight tapered line across that angry air would lead to one sorry tangle after another.

We put our gear together and walked down to the beach, where the lone fisherman looked around and greeted us affably enough, though without slowing or speeding his careful retrieve of a lure. A full-fleshed, big-headed, rather short man with a rosy Pickwickian face, in his middle or late sixties perhaps, he was clearly enough no local. Instead of the stained and rumpled workaday attire that most of us hereabouts favor for such outings, he had on good chest waders, a tan fishing vest whose multiple pouch pockets bulged discreetly here and there, and a neat little tweed porkpie hat that ought to have seemed ridiculous above that large pink face but managed somehow to look just right, jaunty and self-sufficient and good-humored. He was using a dainty graphite rod and a diminutive free-spool casting reel, the sort of equipment you get because you know what you want and are willing to pay for it, and when he cast again, sending a tiny white-feathered spinner bait nearly to the cliff across the way with only a flirt of the rod, I saw that he used them well.

Raising my voice against the rapids’ hiss and chatter, I asked him if the fish were hitting.

“Not bad,” he answered, still fishing. “It was slow this morning when the weather was nice, but this front coming through got things to popping a little. Barometric change, I guess.”

Not the barometer but the wind had me wishing I’d mustered the sense to change to heavier clothing when the soft morning had disappeared. It ruffled the pool’s water darkly, working against the surface current. Younger Daughter, I recalled, had cagily put on a down jacket, and when I looked around for her she was already thirty yards down the beach and casting with absorption, for she was and is disinclined toward talk when water needs to be worked. My Pickwickian friend being evidently of the same persuasion, I intended to pester him no further, though I did wonder whether he’d been catching a preponderance of crappie or of sand bass and searched about with my eyes for a live bag or stringer, but saw none. When I glanced up again he had paused in his casting and was watching me with a wry half-guilty expression much like one I myself employ when country neighbors have caught me in some alien aberration such as fly-fishing or speaking with appreciation about the howls of coyotes.

“I hardly ever keep any,” he said. “I just like fishing for them.”

I said I usually put the sandies back too, but not crappie, whose delicate white flesh my clan prizes above that of all other local species for the table and, if there are many, for tucking away in freezer packets against a time of shortage. He observed that he’d caught no crappie at all. “Ah,” I said, a bilked gourmet. Then, liking the man and feeling I ought to, I asked if our fishing there would bother him.

“No, hell, no,” said Mr. Pickwick. “There’s lots of room, and anyhow I’m moving on up the river. Don’t like to fish in one spot too long. I’m an itchy sort.”

That being more or less what I might have said too had I been enjoying myself there alone when other people barged in, I felt a prick of conscience as I watched him work his way alongside the main rapids, standing in water up to his rubber-clad calves near the shore, casting and retrieving a few times from each spot before sloshing a bit farther upstream. It was rough loud water of a type in which I have seldom had much luck on that river. But then I saw him shoot his spinner-bug out across the wind and drop it with precision into a small slick just below a boulder, where a good thrashing sand bass promptly grabbed it, and watched him let the current and the rod’s lithe spring wear the fish down before he brought it to slack shallow shore water, reaching down to twist the hook deftly from its jaw so that it could drift away. That was damned sure not blind fishing. He knew what he was doing, and I quit worrying about our intrusion on the beach.

By that time Younger Daughter, unruffled by such niceties, had caught and released a small sandy or two herself at the head of the pool, and as I walked down to join her she beached another and held it up with a smile to shame my indolence before dropping it back in the water. I’d been fishing for more than three times as many years as she had been on earth, but she often caught more than I because she stayed with the job, whereas I have a long-standing tendency to stare at birds in willow trees, or study currents and rocks, or chew platitudes with other anglers randomly encountered.

“You better get cracking,” she said. “That puts me three up.”

I looked at the sky, which was uglier than it had been. “What you’d better do,” I told her, “is find the right bait and bag a few crappie for supper pretty fast. This weather is getting ready to go to pieces.”

“Any weather’s good when you’re catching fish,” she said, quoting a dictum I’d once voiced to her while clad in something more warmly waterproof than my present cotton flannel shirt and poplin golfer’s jacket. Nevertheless she was right, so I tied on a light marabou horsehead jig with a spinner—a white one, in part because that was the hue jaunty old Mr. Pickwick had been using with such skill, but mainly because most of the time with sand bass, in Henry Fordish parlance, any color’s fine as long as it’s white. Except that some days they like a preponderance of yellow, and once I saw a fellow winch them in numerously with a saltwater rod and reel and a huge plug that from a distance looked to be lingerie pink.

I started casting far enough up the beach from Younger Daughter that our lines would not get crossed. The northwest wind shoved hard and cold, and the thin rain seemed to be flicking more steadily against my numbing cheeks and hands. But then the horsehead jig found its way into some sort of magical pocket along the line where the rapids’ forceful long tongue rubbed against eddy water drifting up from the pool. Stout sand bass were holding there, eager and aggressive, and without exactly forgetting the weather I was able for a long while to ignore it. I caught three fish in three casts, lost the feel of the pocket’s whereabouts for a time before locating it again and catching two more, then moved on to look for another such place and found it, and afterward found some others still. I gave the fish back to the river, or gave it back to them: shapely, fork-tailed, bright silver creatures with thin dark parallel striping along their sides, gaping rhythmically from the struggle’s exhaustion as they eased away backward from my hand in the slow shallows.

I didn’t wish they were crappie, to be stowed in the mesh live bag and carried off home as food. If it wasn’t a crappie day, it wasn’t, and if satisfactory preparation of the sandies’ rather coarse flesh involves some kitchen mystery from which our family’s cooks have been excluded, the fact remains that they’re quite a bit more pleasant to catch than crappie—stronger and quicker and more desperately resistant to being led shoreward on a threadlike line or a leader. In my own form of piscatorial snobbery, I’ve never much liked the sort of fishing often done for them on reservoirs, where motorboaters race converging on a surfaced feeding school to cast furiously toward its center for a few minutes until it disappears, then wait around for another roaring, rooster-tailed race when that school or another surfaces somewhere else. But my basic snobbery—or trouble, or whatever you want to call it—is that I don’t much like reservoir fishing itself, except sometimes with a canoe in covish waters at dawn, when all good rooster-tailers and water-skiers and other motorized hypermanics are virtuously still abed, storing up energy for another day of loud wave-making pleasure.

In truth, until a few years ago I more or less despised the sand bass as an alien introduced species fit only for such mechanized pursuit in such artificial waters. But in a live stream on light tackle they subvert that sort of purism, snapping up flies or jigs or live minnows with abandon and battling all the way. It isn’t a scholarly sort of angling. Taking them has in it little or none of the taut careful fascination, the studious delicacy of lure and presentation, that go with stalking individual good trout, or even sometimes black bass and bream, but it’s clean fine fishing for all that.

Checking my watch, I found with the common angler’s surprise that nearly three hours had gone a-glimmering since our arrival at the beach, for it was after four. Younger Daughter and I had hardly spoken during that time, drifting closer together or farther apart while we followed our separate hunches as to where fish might be lying. At this point, though, I heard her yell where she stood a hundred yards or so downshore, and when I looked toward her through the rain—real rain now, if light, that gave her figure in its green jacket a pointillist haziness—I saw she was leaning backward with her rod’s doubled-down tip aimed toward something far out in the deep pool, something that was pulling hard.

It was possible that she had hung one of the striped bass that are sometimes found in the river when the crappie and sandies run, and can weigh up to fifteen or twenty pounds. If so, with her frail outfit there wasn’t much prayer that she’d bring him in. But I wanted to be present for the tussle that would take place before she lost him, and I hurried toward her shouting disjointed, unnecessary advice. She was handling the fish well, giving him line when he demanded it and taking some back when he sulked in the depths, by pumping slowly upward with the rod and reeling in fast as she lowered it again. She lost all that gained line and more when he made an upriver dash, and he’d nearly reached the main rapids before we decided he might not stop there and set off at a jogtrot to catch up, Younger Daughter reeling hard all the way to take in slack. But the run against the current tired him, and in a few minutes she brought him to the beach at about the point where we’d met Mr. Pickwick. It was a sand bass rather than a striper, but a very good one for the river. I had no scale along, but estimated the fish would go three and a half pounds easily, maybe nearly four.

“I’m going to keep him,” she said. “We can boil him and freeze him in batches for Kitty, the way Mother did one time. Kitty liked it.”

“All right,” I said, knowing she meant she felt a need to show the rest of the family what she’d caught, but didn’t want to waste it. The wind, I noticed, had abated somewhat, but the cold rain made up for the lack. “Listen,” I said. “I’m pretty wet and my teeth are starting to chatter. Aren’t you about ready to quit?”

A hint of mulishness showed up along her jawline. “You could go sit in the truck with the heater and play the radio,” she said.

I gave vent to a low opinion of that particular idea.

“There’s his hat,” she said. “The man’s.”

Sure enough, there it came, the tweed porkpie, shooting down the rapids upside down and half submerged like a leaky, small, crewless boat, and no longer looking very jaunty. It must have blown off our friend’s head somewhere upstream. Riding the fast tongue of current to where the pool grew deep, it slowed, and I went down and cast at it with a treble-hooked floating plug till I snagged it and reeled it in.

“I guess we can drive up and down and find his car, if we don’t see him,” I said. “It’s a pretty nice hat.”

She said in strange reply, “Oh!”

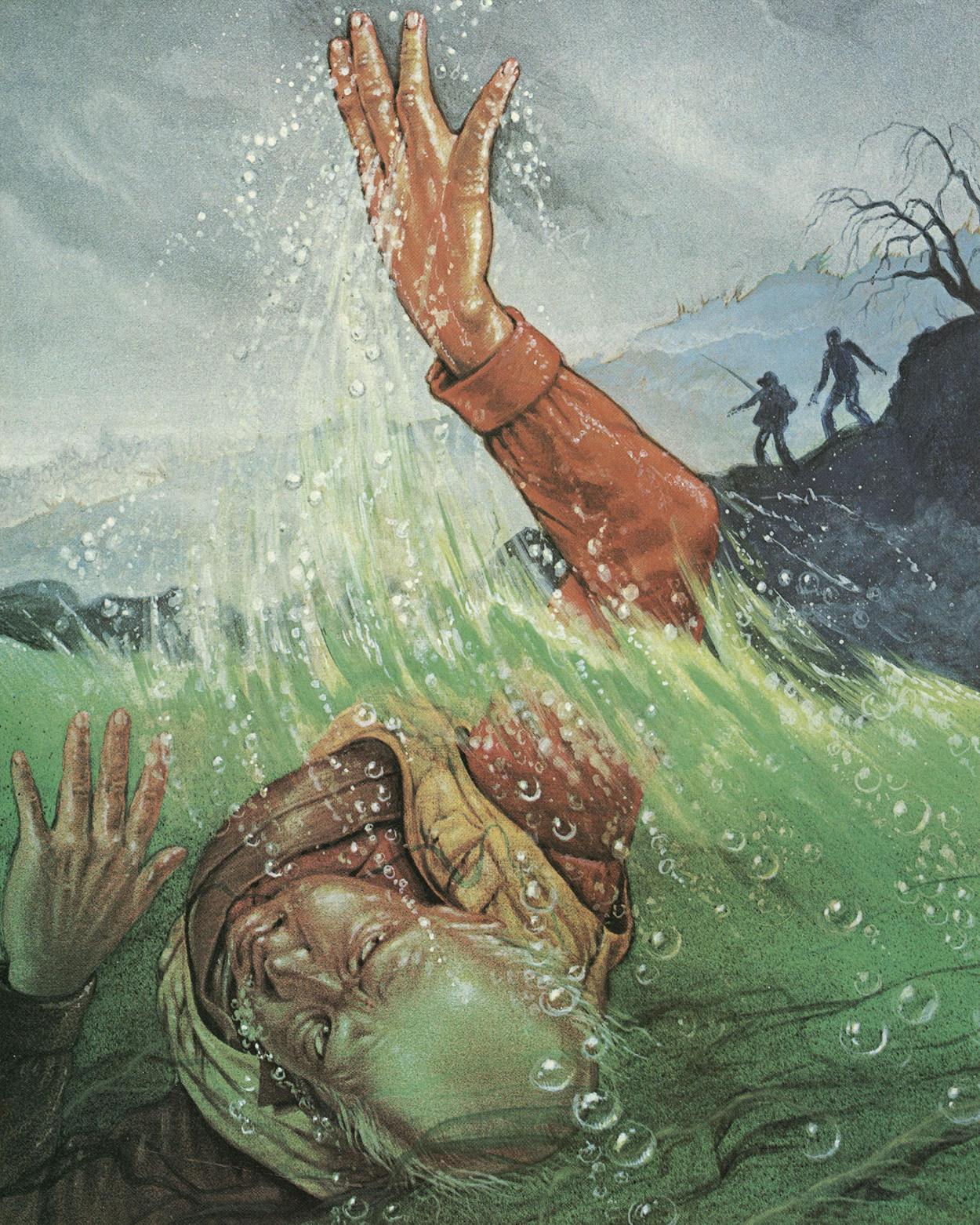

The reason turned out to be that Mr. Pickwick was cruising downriver along the same swift route his hat had taken but quite a bit more soggily, since his heavy chest waders swamped full of water were pulling him toward the bottom as he came. He was in the lower, deepening part of the rapids above us, floating backward in the current—or rather not floating, for as I watched I saw him vanish beneath surging water for five or six long seconds, surfacing enormously again as his large pink bald head and his shoulders and rowing arms broke into sight and he took deep gasps of air, maintaining himself symmetrically fore and aft in the river’s heavy shove. He stayed up only a few moments before being pulled under again, then reappeared and sucked in more great drafts of air. It had a rhythmic pattern, I could see. He was bending his legs as he sank and kicking hard upward when he touched bottom, and by staying aligned in the current he was keeping it from seizing and tumbling him. He was in control, for the moment at any rate, and I felt the same admiration for him that I’d felt earlier while watching him fish.

I felt also a flash of odd but quite potent reluctance to meddle in the least with his competent, private, downriver progress, or even for that matter to let him know we were witnesses to his plight. Except that, of course, very shortly he was going to be navigating in twelve or fifteen feet of slowing water at the head of the pool, with the waders still dragging him down, and it seemed improbable that any pattern he might work out at that extremely private point was going to do him much good.

Because of that queer reluctance I put an absurd question to the back of his pink pate when it next rose into view. I shouted above the hoarse voice of the water, “Are you all right?”

Still concentrating on his fore-and-aftness and sucking hard for air, he gave no sign of having heard before he once more sounded, but on his next upward heave he gulped in a breath and rolled his head around to glare at me over his shoulder, out of one long blue bloodshot eye. Shaping the word with care, he yelled from the depths of his throat, “No!”

And went promptly under again.

Trying to gauge water speed and depth and distances, I ran a few steps down the beach and charged in, waving Younger Daughter back when she made a move to follow. I’m not a powerful swimmer even when stripped down, and I knew I’d have to grab him with my boots planted on the bottom if I could. Nor will I deny feeling a touch of panic when I got to the edge of the gentle eddy water, up to my nipples and spookily light-footed with my body’s buoyancy, and was brushed by the edge of the rapids’ violent tongue and sensed the gravel riverbed’s sudden downward slant. No heroics were required, though—fortunately, for they’d likely have drowned us both, with the help of those deadweight waders. Mr. Pickwick made one of his mighty, hippolike surfacings not eight feet upriver from me and only an arm’s length outward in the bad tongue water, and as he sailed loggily past I snatched a hold on the collar of his many-pocketed vest and let the current swing him round till he too was in the slack eddy, much as one fishes a lure or a fly in such places. Then I towed him in.

Ashore, he sat crumpled on a big rock and stared wide-eyed at his feet and drank up air in huge, sobbing, grateful gasps. All his pinkness had gone gray-blue, no jauntiness was in sight, and he even seemed less full-fleshed now, shrunken, his wet fringe of gray hair plastered vertically down beside gray ears. Younger Daughter hovered near him and made the subdued cooing sounds she uses with puppies and baby goats, but I stared at the stone cliff across the Brazos through the haze of thin rain, waiting with more than a tinge of embarrassment for his breathing to grow less labored. I had only a snap notion of what this man was like, but it told me he didn’t deserve being watched while he was helpless. Maybe no one does.

He said at last, “I never had that happen before.”

I said, “It’s a pretty tough river when it’s up.”

“They all are,” he answered shortly and breathed a little more, still staring down.

He said, “It was my knees. I was crossing at the head of this chute, coming back downriver. They just buckled in the current and whoosh, by God, there we went.”

“We’ve got your hat,” Younger Daughter told him as though she hoped that might set things right.

“Thank you, sweet lady,” he said, and smiled as best he could.

“That was some beautiful tackle you lost,” I said. “At least I guess it’s lost.”

“It’s lost, all right,” said Mr. Pickwick. “Good-bye to it. It doesn’t amount to much when you think what I . . .”

But that was a direction I somehow didn’t want the talk to take, nor did I think he wanted it to go there either. I was god-awfully cold in my soaked, clinging, skimpy clothes and knew he must be even colder, exhausted as he was. I said I wished I had a drink to offer him. He said he appreciated the thought, but he could and would offer me one if we could get to his car a quarter-mile down the shore, and I sent Younger Daughter trotting off with his keys to drive it back to where we were. The whiskey was nice sour-mash stuff, though corrosive skid row swill would have tasted fine just then. We peeled him out of the deadly waders and got him into some insulated coveralls that were in his car, and after a little he began to pinken up again, but still with the crumpled shrunken look.

He and I talked for a bit, sipping the good whiskey straight from plastic cups. He was a retired grain dealer from Kentucky, and what he did mainly now was fish. He and his wife had a travel trailer in which they usually wintered on the Texas coast near Padre Island, where he worked the redfish and speckled trout of the bays with popping gear or sometimes a fly rod when the wind and water were right. Then in February they would start a slow zigzag journey north to bring them home for spring. He’d even fished steelhead in British Columbia—the prettiest of all, he said, the high green wooded mountains dropping steeply to fjords and the cold strong rivers flowing in from their narrow valleys.

When we parted he came as close as he could to saying the thing that neither he nor I wanted him to have to say. He said, “I want . . . Damn, I never had that happen to me before.” and stopped. Then he said, “Jesus, I’m glad you were there.”

“You’d have been all right,” I said. “You were doing fine.”

But he shook his strangely shrunken pink head without smiling, and when I turned away he clapped my shoulder and briefly gripped it.

In the pickup as we drove toward home, Younger Daughter was very quiet for a while. I was thinking about the terrible swiftness with which old age could descend, for that was what we’d been watching even if I’d tried not to know it. I felt intensely the health and strength of my own solid body, warmed now by the whiskey and by a fine blast from the pickup’s heater fan. If on the whole I hadn’t treated it as carefully as I might have over the years, this body, and if in consequence it was a little battered and overweight and had had a few things wrong with it from time to time, it had nonetheless served me and served me well, and was still doing so. It housed whatever brains and abilities I could claim to have and carried out their dictates, and it functioned for the physical things I liked to do, fishing and hunting and country work and the rest. It had been and was a very satisfactory body.

But it was only ten or twelve years younger than the old grain dealer’s, at most, and I had to wonder now what sort of sickness or accident or other disruption of function—what buckling of knee, what tremor of hand, what milkiness of vision, what fragility of bone, what thinness of artery wall—would be needed, when the time came, to push me over into knowledge that I myself was old. Having to admit it, that was the thing.

Then, with the astonishment the young bring to a recognition that tired, solemn, ancient phrases have meaning, my daughter uttered what I hadn’t wanted to hear the old man say. She said, “You saved his life!”

“Maybe so,” I said. “We just happened to be on hand.”

She was silent for a time longer, staring out the window at the rain that fell on passing fields and woods. Finally she said, “That’s a good fish I caught.”

“Damn right it is,” I said.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Fishing