Even some Texans don’t know what to make of Lubbock. How can it be so flat? How can such a large city exist in the middle of such desolation? Why would anybody live there? People who do live there tend to smile at such obvious questions. “What you see as bleak and ugly,” says Johnny Hughes, the former manager of the Joe Ely Band, “we don’t. We see it as beautiful.”

Perhaps. Yet when most outsiders use the words “beauty” and “Lubbock” in the same sentence, they aren’t talking about the brown, blasted landscape. They’re referring to something like Jimmie Dale Gilmore’s high, lonesome voice, or Buddy Holly’s deceptively simple rock and roll, or Terry Allen’s elaborate story songs. They’re talking about Lubbock music, and a beauty that, like the terrain’s, is not typical. Indeed, the question Lubbockites get asked more than any other is, How could so much music come out of this windy wasteland? For two generations, Lubbock has produced an unsurpassed number of rock icons and country superstars, brilliant weirdos and working stiffs: Holly, Ely, Gilmore, and Allen, as well as Waylon Jennings, Natalie Maines, Butch Hancock, Tommy Hancock, Jo Carol Pierce, Norman Odam (a.k.a. the Legendary Stardust Cowboy), Delbert McClinton, Sonny Curtis, Mac Davis, John Denver (who went to Texas Tech) and Meat Loaf (who went to Lubbock Christian College). The common denominator connecting them all is “a reckless energy,” says Don Caldwell, who owns Caldwell Studios, a Lubbock recording complex. “Regardless of the style that’s being played, there’s an approach and an attack that comes with the players out here that’s real identifiable.”

How did such a gifted bunch happen to hail from the same place? One simple, unsatisfying reason is that all roads lead to Lubbock. Many musicians grew up on farms and in small towns in the Panhandle and moved to one of the biggest cities around. Long before, in the 1870’s, millions of cows were driven through the area by thousands of cowboys, who wrote and sang songs that would become country music staples. As cotton emerged as a thriving industry in the thirties, Lubbock came to be known as the Hub City of the Plains, because of the four highways that intersect there.

Though the hub has its whimsical side—Lubbock had a town band in the early twentieth century—it is also a city with more churches per capita than any other in the country, one in which you couldn’t buy alcohol until 1972 and still can’t buy a beer in a grocery store. And so, for many musicians, all roads lead away from Lubbock too.

Still, when they look back, it’s usually with affection—and a certain amount of bewilderment. Why Lubbock? Even from a distance, it’s hard to know what to make of it.

The Interviewees

Jo Harvey Allen is an actress and a playwright. She lives in Santa Fe.

Terry Allen, Jo Harvey’s husband, is a singer-songwriter and an artist. He lives in Santa Fe.

Sonny Curtis plays guitar in the Crickets, which was once Buddy Holly’s band. He lives in Nashville.

Joe Ely is a singer-songwriter. He lives in Austin.

Lanny Fiel plays fiddle, guitar, and piano in the Ranch Dance Fiddle Band and teaches traditional country music to children and teenagers. He lives in Lubbock.

Jimmie Dale Gilmore is a singer-songwriter. He lives in Austin.

David Halley is a singer-songwriter. He lives in Nashville.

Butch Hancock is a singer-songwriter. He lives in Terlingua.

Charlene Hancock, the wife of Tommy X Hancock and the mother of Conni and Traci Lamar Hancock, sings and plays keyboard bass in the Texana Dames. She lives in Austin.

Conni Hancock sings and plays guitar in the Texana Dames. She lives in Austin.

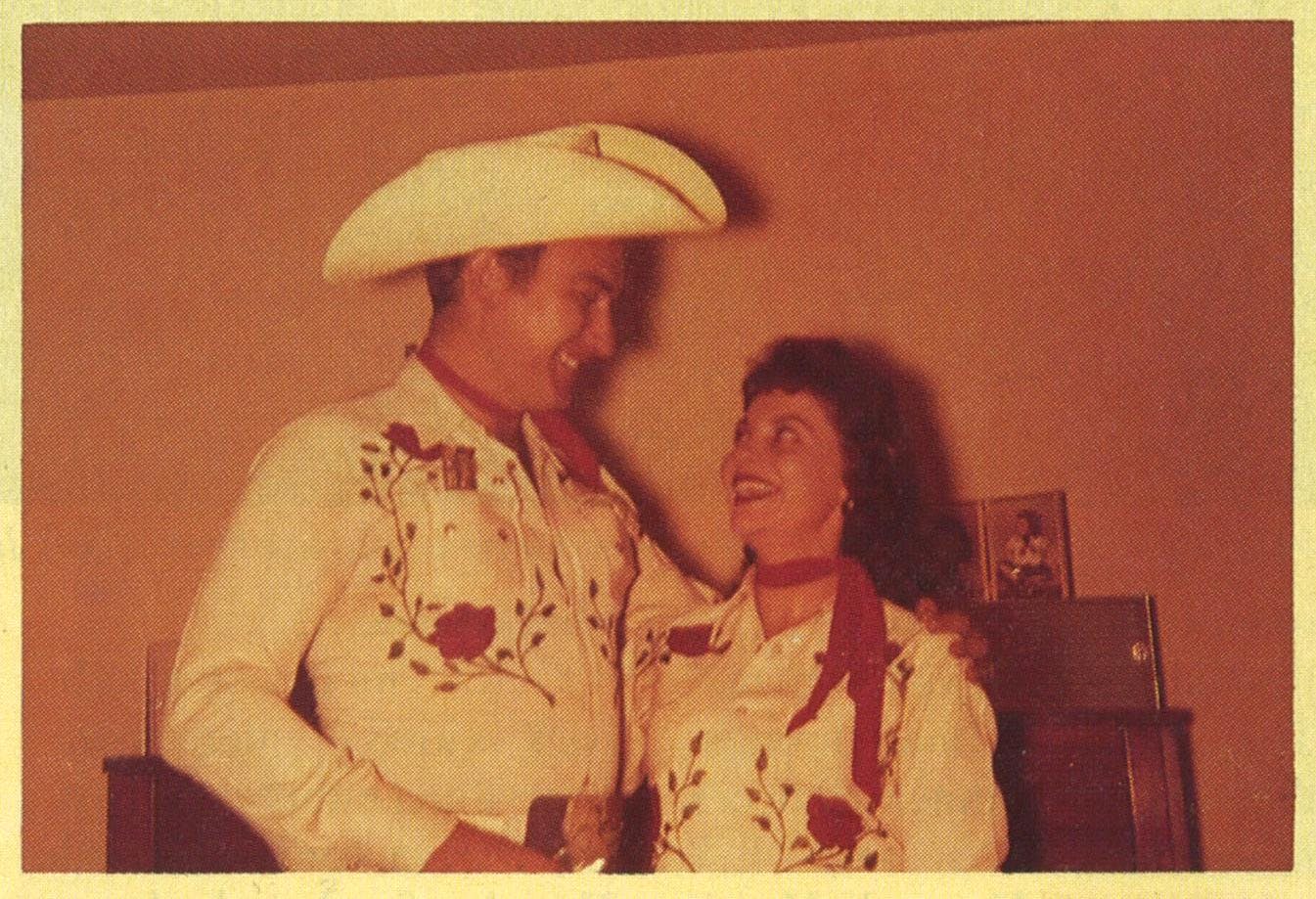

Tommy X Hancock is a singer-songwriter, fiddler, and guitarist. He lives in Austin.

Traci Lamar Hancock sings and plays accordion in the Texana Dames. She lives in Austin.

Carolyn Hester is a singer-songwriter. She lives in Los Angeles.

Johnny Hughes formerly managed the Joe Ely Band. He lives in Lubbock, where he is the director of the Petroleum Land Management program at Texas Tech University.

Waylon Jennings is a singer-songwriter. He lives in Nashville.

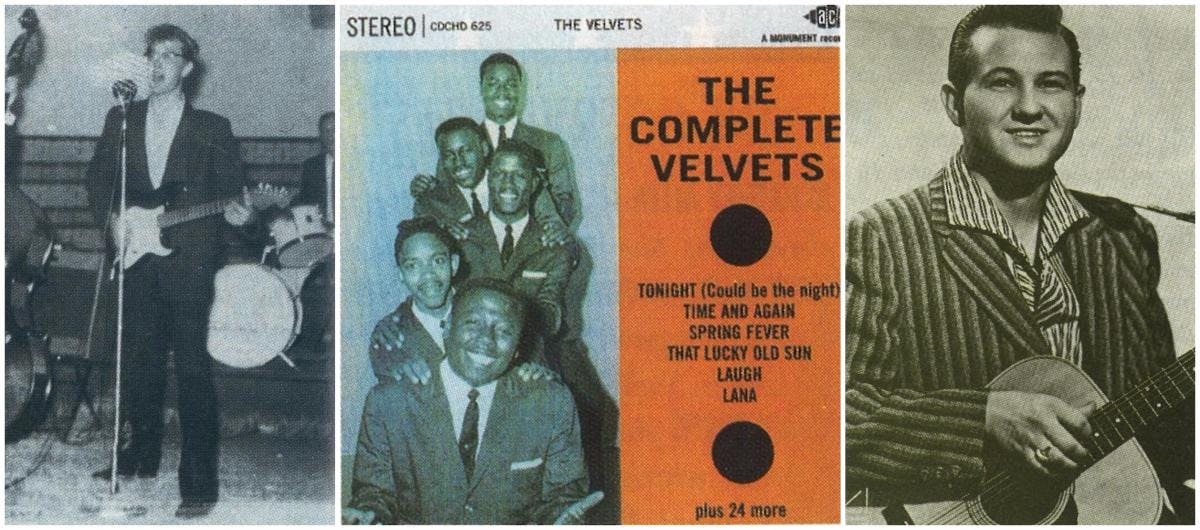

Virgil Johnson was the lead singer and principal songwriter for the Velvets. He lives in Lubbock, where he is a deejay at KDAV-AM.

Guy Juke is an artist and plays guitar for the Cornell Hurd Band. He lives in Austin.

Bobby Keys played saxophone for, among others, the Rolling Stones, the Beatles, and Elvis Presley. He lives in Nashville.

Kenny Maines sings and plays guitar and harmonica for the Maines Brothers. He lives in Lubbock, where he is a county commissioner.

Lloyd Maines is a record producer and plays pedal steel guitar for the Maines Brothers, the Dixie Chicks, and Robert Earl Keen’s band, among others. He lives in Austin.

Steve Maines sings and plays guitar for the Maines Brothers. He lives in Lubbock, where he manages one of the state’s child support enforcement offices.

Davis McLarty was a drummer for the Joe Ely Band. He lives in Austin, where he is a booking agent for several acts, including Kelly Willis and Richard Buckner.

Delbert McClinton is a singer. He lives in Nashville.

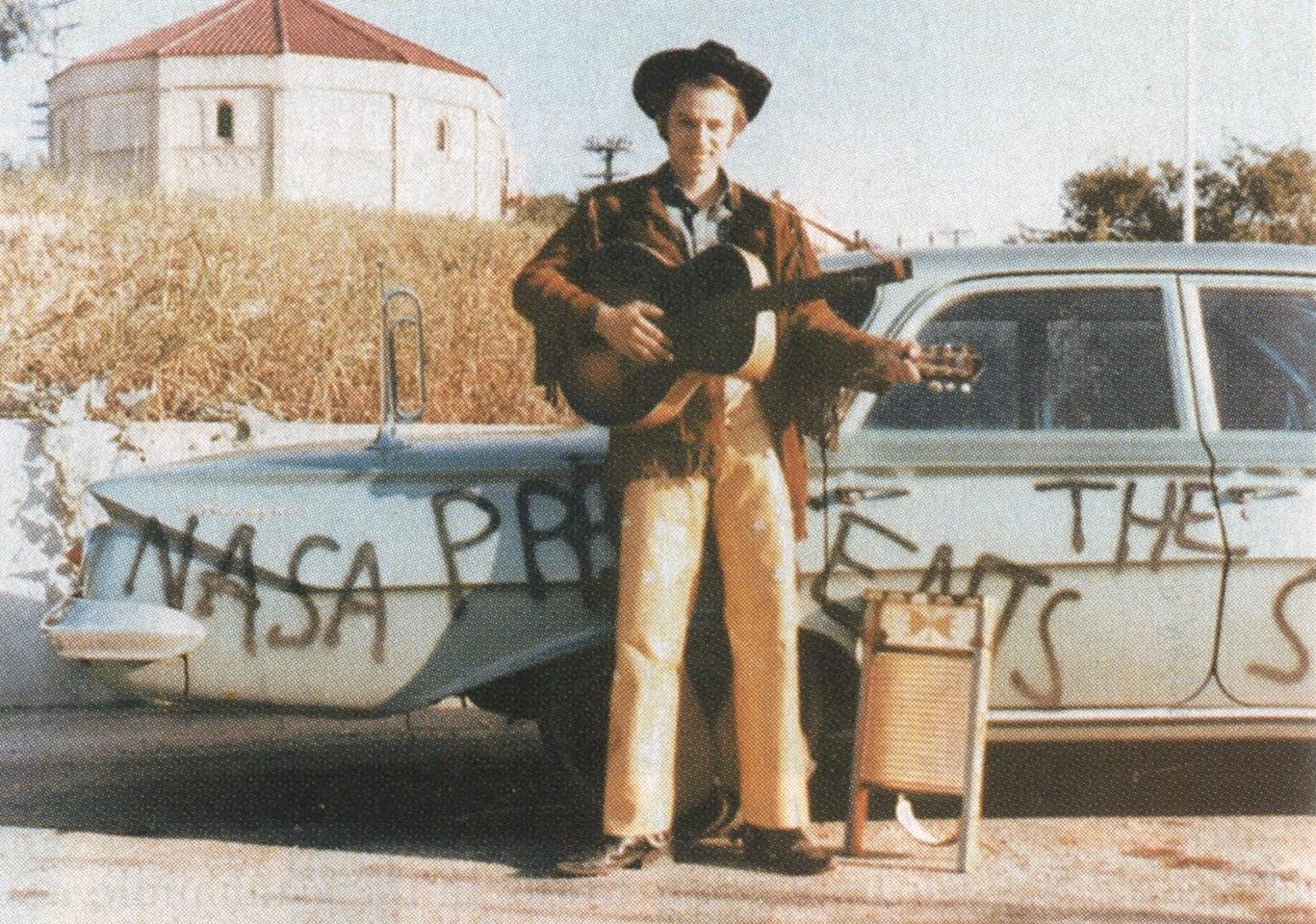

Norman Odam is a singer-songwriter who performs as the Legendary Stardust Cowboy. He lives in San Jose, California.

Jo Carol Pierce is a singer-songwriter and a playwright. She lives in Austin.

Angela Strehli is a singer. She lives in San Francisco.

Rob Weiner has edited a book about the Grateful Dead. He lives in Lubbock, where he is a reference librarian at the Mahon Library.

You Either Go Crazy or You Play Music

Guy Juke Alien implantation of fetuses from the Lubbock Lights is my theory. Aliens, in order to enter society, go through the pregnant woman. They send their mind through that. And then Butch Hancock is born.

Davis McLarty My uncle Marvin actually saw the Lubbock Lights because he worked at the Circle Drive-In—he guarded the exit to make sure no one was sneaking in. He said they weren’t flying saucers; they were low-flying geese on one of those weird West Texas … you know the way the sky gets so weird and the light reflects funny?

Delbert McClinton Hell, I don’t know. I think maybe it was the DDT trucks that drove up and down the alleys we used to run behind. Maybe that’s what caused it.

McLarty The layout of Lubbock is kind of interesting. Everything either goes east and west or north and south. There’s a fixed circle that goes around the whole city, and then on the inside, it’s all squares. I don’t know if that has anything to do with it, but it’s sort of like sheet music.

Norman Odam Well, there was nothing else to do there!

McClinton You either go crazy or play music in Lubbock. There’s not a hell of a lot to do.

Charlene Hancock The energy behind Lubbock music, whatever style it is, seems to have a lot of force. I know it’s because of that darn wind.

Angela Strehli You had to have an imagination to fill in the blanks.

Joe Ely Every time I go back, there’s something about that whole area that seems to want to turn into a song. There’s something musical about that emptiness. I can’t ever drive up there without music coming into my head. It helps fill up the space.

Terry Allen The isolation and the geography and the weather and the starkness—all of these things play big roles. To this day, I love to see a flat horizon; there’s something that makes me take a deep breath. And then, in those days, I think it was just the fact that you were completely surrounded by this horizon, that any kind of thing could come over at any minute, like a tornado or a killer or whatever. But your eye always went to it, and your imagination always went to it, because that was kind of the secret door out.

Jo Harvey Allen There was this thing about the horizon in that flat country. When you were out playing, you loved to look and say “Oh, yeah, the earth is round.” And you would be right in the middle of it. I’ve always thought that being in that spot gave you this feeling that you were the center of the universe, that you were really special, and at the same time you were just a speck of absolute nothing.

Conni Hancock When I was a little kid, I would go to my grandmother’s house, between Lubbock and Amarillo, and a lot of times we would be coming back at night. Those cotton fields were so black, and really, there weren’t many lights in Lubbock. I can remember looking at a speck of light and thinking, “That could be my house; that speck could be my whole world.” I would contemplate perspective a lot because everything was so flat, and there was so much sky. I remember when they built the loop around Lubbock, the overpasses. It was a big deal. And when my dad would take me downtown to run errands with him, we would go to the cafe on top of the Great Plains Life Insurance building. I could just stare out that window for hours and hours because, for once, I wasn’t just on flat ground. It was like becoming a living figure.

Pianos in Every House

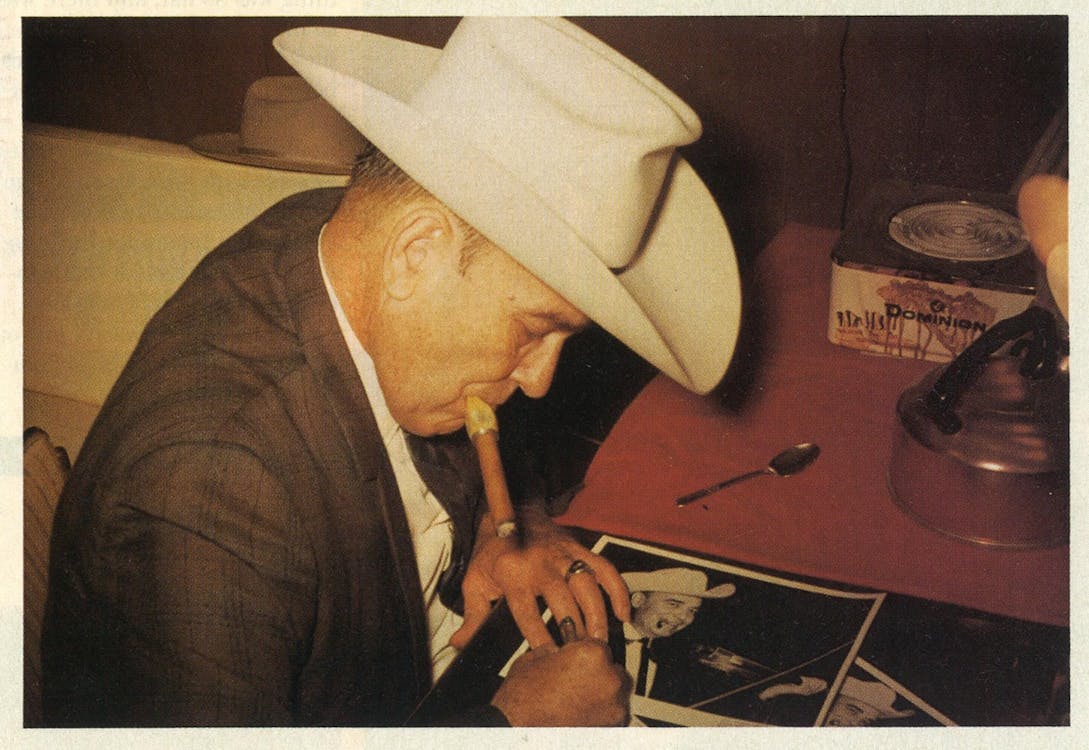

Waylon Jennings Music was our entertainment, especially when I was growing up, in the forties. Every other house had a piano or a fiddle or a guitar, and somebody knew how to play it. Music was the only thing we had—it was a big part of growing up.

Sonny Curtis We used to go to people’s houses when I was a kid, you know, to visit, and they’d have a party, and man, whatever you had—if it was an accordion or a guitar or whatever—you’d bring it along. Some people would break off and play dominoes, and others would go into the living room and play their fiddles and guitars and their accordions and whatever.

McClinton When I was a little guy, my parents would go to the Cotton Club and dance to Bob Wills and all the kids would play in the parking lot. We used to lean in the windows or peak in the door. And we could always hear the music.

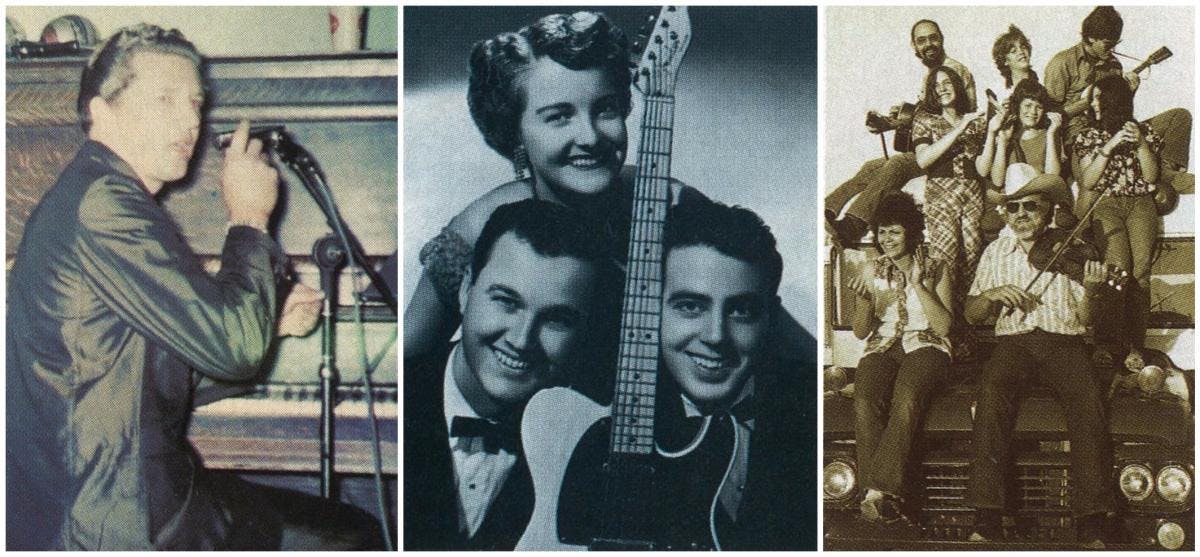

Tommy X Hancock Every little town around Lubbock had a jamboree, and all the amateur bands played. Fifty miles of anybody every Saturday night.

Charlene Hancock Anybody was invited to play or sing or do their thing. And you didn’t have to be good.

Curtis People would get together for these musicals on Saturday night or whenever, and well, if you had a trumpet, you’d bring a trumpet. A whole bunch of different styles came together. I think Bob Wills’ style was started that way. Man, he had a clarinet in the band at one time and a trumpet and a fiddle and, you know, just whatever.

Kenny Maines I have always had a theory that the reason Lubbock established a unique sound is that we had people like Bob Wills and Buddy Holly. There were a lot of similarities in what they did—they were both pretty radical in what they were doing at the time. And growing up in that area, we would try to imitate those types of sounds. We failed at doing that, but in the attempt, maybe we created something else altogether, because we were bad imitators. That helped create our own sound.

We Drove Our Mom and Dad Crazy

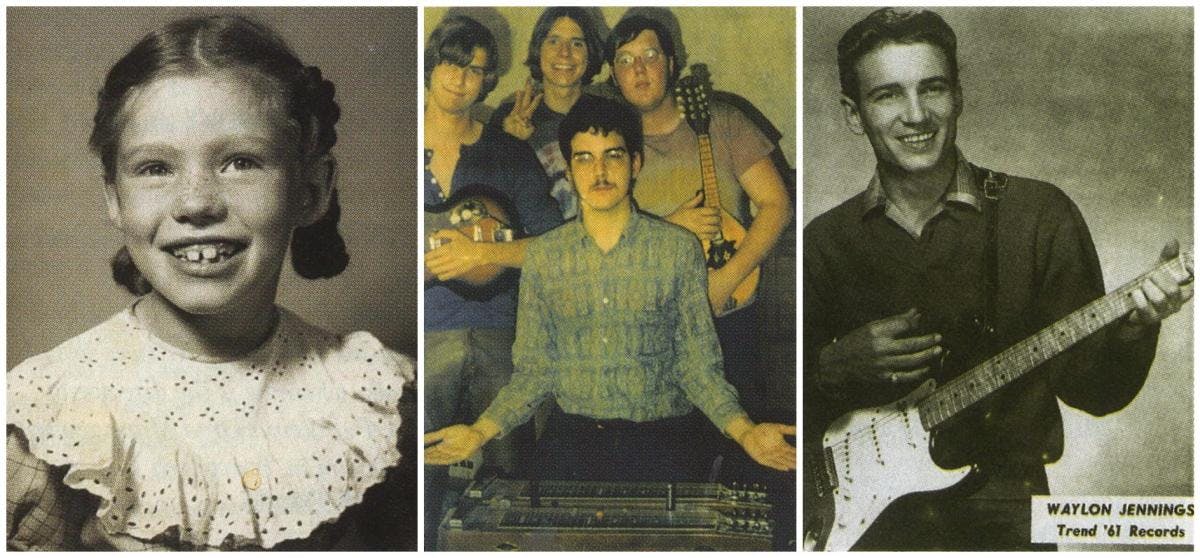

Charlene Hancock The generations of musicians who have come up have grandparents and great-grandparents who played music.

Lanny Fiel [Fiddler] Frankie McWhorter used to sing at home with his mom. People around here grew up singing songs—it was just part of everyday life. They weren’t imitating this and imitating that. People were playing music they’d heard directly from somebody, not influenced and bombarded by all these different things.

Kenny Maines It was part of family activities: On Saturday or Sunday afternoons people would gather round for entertainment. You had to find something, and so it seemed like music was the easiest and most convenient. At one time there was actually an exhibit at the museum in Lubbock called “Nothin’ Else to Do.”

Fiel The “nothin’ else to do” thing is coming from the perspective of a person born in this culture at this time. In the early days nobody knew “nothin’ else to do.” Literally, you were working your butt off to stay alive. You didn’t know what a radio was or a TV or free time.

Curtis Our family was certainly into music big-time. I think we drove our mom and dad crazy, my two brothers and me. My brothers played fiddle and guitar. We were real big bluegrass fans. As a matter of fact, our uncles, the Mayfield Brothers, were a bluegrass band, and Edd Mayfield, who was a big influence on me as a guitar player, played guitar and sang with Bill Monroe and the Bluegrass Boys.

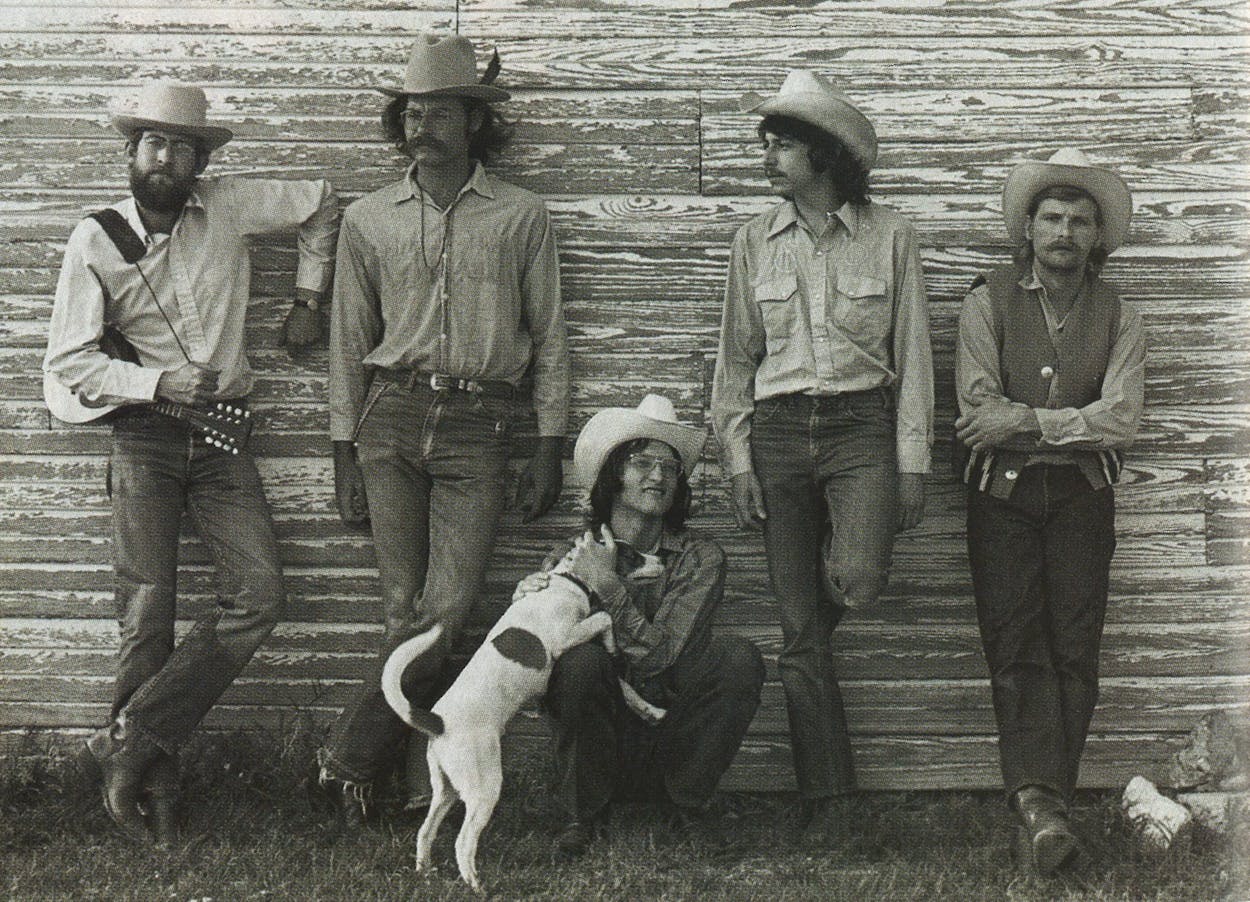

Ely When I got the first version of my band together, with Lloyd [Maines] and Jesse [Taylor], Steve Keeton and Gregg Wright and Rick Hulett, we were all talking, setting up at the Cotton Club. Everybody knew that everybody else’s daddy, except for mine, had played in bands, but they started talking, and by the end of the conversation, they realized that at one time, their daddies all played in the same band together. Which was pretty amazing.

Lloyd Maines When we were kids, six or seven or eight years old, we would sit on my grandmother’s floor and watch my dad and uncles have these kind of jam sessions, singing sessions. This was before any of us had thought about doing anything, but I’m sure it had kind of an osmosis effect on us. Then [my daughter] Natalie [the lead singer of the Dixie Chicks] did the same thing. Whenever the Maines Brothers were playing locally in the early eighties, she came to those gigs. She never got up and sang, although I knew she was a good singer. She liked to just sit back and enjoy it and soak it all in.

The Radio Was Everything to Me

Jo Carol Pierce There were great radio stations that came in the night. I was fascinated with that world, and I couldn’t wait for night.

Jimmie Dale Gilmore I have this sense of late-night radio in the car out there—that’s just one of my visions of heaven.

Butch Hancock There’s nothing like coming up from Post, up onto the Caprock at night, and all of a sudden you can get the radio stations.

Ely We used to pick up XERF, the old station out of Mexico that was Wolfman Jack’s station—the only place that played blues and old country stuff, gospel.

Strehli I liked WLAC out of Nashville, and there was a Shreveport station, KWKH, that had a great blues show. The radio was everything to me. I heard all kinds of music on the radio, but when I heard the blues, it really bent my ear. I didn’t know what to call it or anything, and I didn’t have any idea where it came from. So in the years after that, I was just sort of looking around and trying to find it.

Jennings “The Louisiana Hayride” was the thing for country music. And, of course, [the broadcasts of] the Opry in Nashville. Then there was KDAV in Lubbock, which I believe was the very first full-time country station in the entire nation.

Practice or Plough

Jennings Lubbock was almost a way out of the cotton fields. We were all farm boys, and we knew there was a better way somewhere.

Virgil Johnson This is an agricultural area, so when you got off one evening and you weren’t too tired, before you took the tub off the side of the house and took a bath, you would probably do a little singing. You would strum on a guitar. That was the thing—to learn and play a guitar, to learn and play a piano. And so you had a little pastime. It’s not now as it was then. Now a kid gets in his BMW and sees how fast it’ll go to the next streetlight. But during that particular time, you couldn’t go out and get on the wagon and ride around in a square. So more than likely, what you would do is you would harmonize. You would vocalize. You would get with your friends, you would come up with a tune, or you would try and emulate someone that you had heard on the radio.

Fiel Joe Stephenson’s dad wanted him to play fiddle so bad that he offered him a deal. He said, “You can practice or plough.” And Joe became the 1968 Texas fiddle champion. Same thing with Bob Wills. He’d rather be playing and making money in that than working in those cotton fields, but that’s what he did for the longest time.

Jennings Well, anybody who spends his life in a cotton patch is going to be weird or unique. I learned a song one time while I was working out there. I was about fifteen. I had a piece of paper in my pocket, and “The Last Letter” was the name of the song—a country song. What I would do was look at it on one row, at one end, and pull cotton all the way until the other end, and try to not look at the piece of the paper until I had memorized the song.

Hancock While we were there, Lubbock went from being a tiny little cotton farming town—where agriculture was the main industry—to Texas Tech becoming the major industry.

Gilmore In certain ways Lubbock was a typical middle-America town. It was one of those examples of the explosion after WWII. We were the first generation off of the farm, so we had the real rural culture in us, but at the same time, we were slammed into the twentieth century.

Lust, Sin, Death

Kenny Maines Our father’s father grew up in a church music family. He and his brothers—my dad’s uncles—sang at the church. Afterward, they would gather for meals.

Johnson There were no doo-wops here. I would sing with spiritual groups. I did some singing in church. Most singers began in church.

Rob Weiner Lubbock has all of these religious traditions: Baptist, Pentecostal, Church of Christ, Methodist, Presbyterian, Mormon. On just about every corner, no matter where you go, there’s a church and a restaurant. You sing in church, you go to a restaurant, you sing later.

McLarty Lots of churches with signs and little slogans like “LSD: Lust, Sin, Death.” I thought, “Hmmm, maybe I’ll try it.”

Pierce The meanness of the town drove us all closer in, for defense. People were extremely conservative. They were blaming everything on Communists and were terrified that their youth would become Communist and were just terrified of any originality or anything. So I think that kind of goaded us into a rebellion.

Terry Allen They had record burnings at the fair grounds. People would say that if you keep listening to this rock and roll music, you’re going to turn into a homosexual, you’re going to turn into a criminal, you’re going to turn into a “nigger.” You’re going to be literally transformed into one of these hideous things. Then you had at the same time the same people in lots of cases telling all of these outrageous, wonderful stories about the Depression, about the war, about whatever. You’d go over to someone’s house for supper, and someone’s mom or dad would tell you some story. So there was that openness—an atmosphere that opened you up to your imagination. And then at the same time, all of these forces were trying to shut it down.

That Little Studio

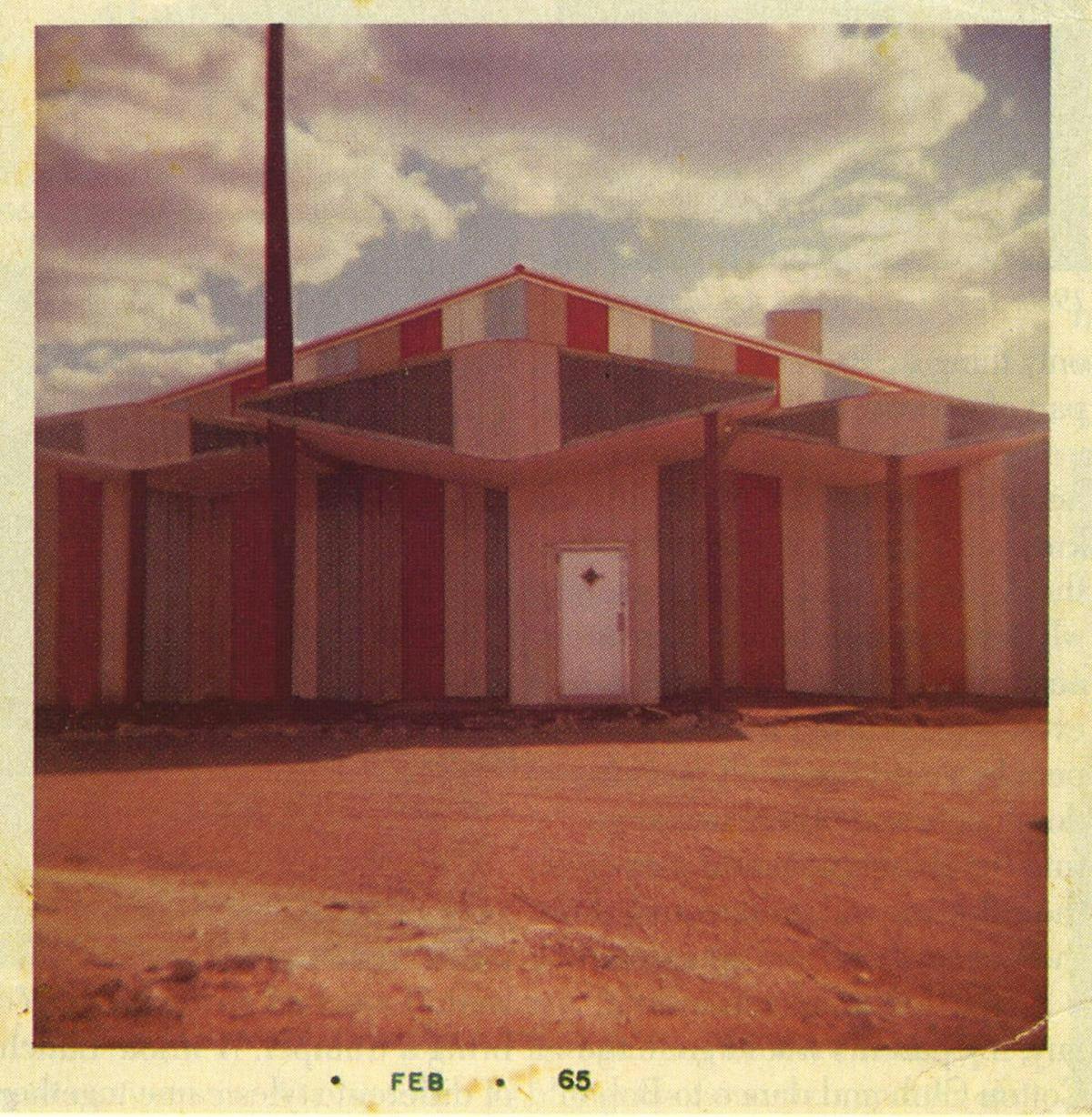

Carolyn Hester Norman Petty’s studio in Clovis was probably the best studio within hundreds of miles. I made my first album there when I was twenty. The studio itself was built on Norman’s dad’s gas station. His dad repaired cars and sold gas in the daytime. At night it would close, and we would start to tape at six or seven. Of course, you would chow down big-time before, and then you’d start recording. At six in the morning they brought out the little cots, and everybody went to sleep.

Jennings I was down there not too long ago. I can’t believe it was that little. That little studio.

Hester My album came out in 1958, and I was one of the few people on the New York City folk scene with a major label recording. Between all that, I met Buddy and the Crickets, and Buddy would call me sometimes when he came to the city. Years later, it turned out, when I met a certain harmonica player named Bob Dylan, he wanted to get to know me because I had known Buddy Holly. By that time Buddy was dead. Bob opened for me at a club in Boston, and I told him, “Well, the next thing I’m going to do is make a record for Columbia. You know John Hammond is signing folk artists. Do you want to come play harmonica?” He said, “Yeah, here’s my phone number.” Then I said to [Hammond], “I’ve got a new friend playing harmonica. That’s Bob Dylan.” And so he says, “Could I hear the band? Could you, say, do a rehearsal I could come to?” And so he came down to the Village for our rehearsal. At that time I was married to [singer-songwriter] Richard Farina, so he was at that rehearsal also. We all sat around a dining table except for Bill Lee [director Spike Lee’s father], who stood up because he had an upright bass. Dylan and John Hammond sat next to each other, and Bob just had his harmonica—there wasn’t much elbow room there. John’s eyes lit up. He loved my band. So that’s how all that happened. More than I realized, everything in my life related to Clovis.

Everybody Played a Stratocaster

Bobby Keys After Elvis came on the scene, all of a sudden guys that I was playing Little League baseball with the year before had guitars the next summer. Man, there was a lot of activity going on in garages, a lot of three-chord activity.

Ely When I first got to Lubbock from Amarillo, everybody I ran into was a musician. It seemed like after Buddy Holly died, bands just spread like crazy. Everybody played a Stratocaster. And everybody had a band. So I got in with all the bands around there and put one together myself when I was in the eighth grade or something.

Terry Allen Rock and roll hit Lubbock like a bomb. The whole beatnik thing. Lubbock had its squirrely coffee shops, and there was always some girl in a leotard saying poems to some guy playing his bongos. And everybody started wearing their sunglasses at night.

Ely I guess the fact that there’s a big university there brought in a diverse culture. There was a kind of Lubbock Underground, and the musicians knew each other and all lived in a different world than the cotton farmers and the people who had to make a living off the land. There was a real sense of community.

Johnny Hughes We were outsiders. We were hippies before there were hippies.

Fiel Well, I’d say back in sixty-five and sixty-six, you could count on one hand the number of guys with long hair in Lubbock. The ones I knew were Joe Ely, Lewis Cowdrey, Lance Copeland, and my brother, and me, wanting to be like them.

David Halley When I was growing up, I never thought of country music as possessing the qualities of an art form. And when I first saw the Flatlanders [Gilmore, Ely, and Butch Hancock’s mythic sixties band], it was conceptual art. It was like, “Oh, you mean smart country music, spiritual country music? Country music that has all these kind of hippie issues—everything from the beat generation to Bob Dylan—but put it in a traditional country framework?” To me, that combination of elements was a real folk-art masterstroke.

A Melting Pot

Fiel You’ve got so many influences that converge out here from different cultures, and different people hearing all kinds of different things. I don’t know if there’s another place in the United States where it’s quite this mixed: blues, jazz, Mexican music, all those folk traditions, old Celtic folk tunes, all those traditions coming together in one spot.

Terry Allen You couldn’t call it urban in any sense, but it was the largest town in about three hundred or four hundred miles in any direction. So it was a center, and I think that it did have access to things that a place like Wichita Falls didn’t.

Lloyd Maines Lubbock was sort of a stopover point for a lot of touring bands. They would go to Amarillo or Lubbock or both when they were traveling from the East Coast to the West Coast.

Terry Allen Black music was a huge influence on Lubbock music. The Cotton Club had a lot of touring black bands in the mid-fifties, when rock and roll came together. We used to go there when I was eleven or twelve, and they would let us in the back because we wanted to hear someone like Jimmy Reed or Bo Diddley. And they always let us in.

Hughes All these Mexican migrant workers would come in to pick the cotton, and they just filled downtown on Sundays. They’d all come in from miles around. You had the accordions and conjunto, and all the different things they brought with them.

Curtis There was a Mexican cafe across the street from us in Meadow [25 miles southwest of Lubbock] when I was a real small child, and I used to love to go sit on the front porch in the evenings. They’d have a jukebox or a radio or something playing a Mexican radio station, and you’d hear these terrific Mexican songs floating through the air. It really was a melting pot.

Conni Hancock Whenever we meet someone like Flaco Jimenez and he finds out we’re from Lubbock, he says he remembers it affectionately. That always surprises me, because we grew up with a lot of racism there. I’m surprised that people like him would like it. But apparently they just stayed in their culture and had a good time.

Tommy X Hancock The races were really split up there until recently. In fact, the Cotton Club was the only place they ever mixed at all.

As Rough and Rowdy a Scene as Ever Was

Terry Allen My dad, Sled Allen, got a little defunct gospel church in Lubbock. He rented out the space and started throwing dances and, eventually, wrestling matches and boxing matches. Then it moved to bigger spaces. He became a local promoter of entertainment in Lubbock. He brought in some of the very first rock and roll and country shows. He had a place called the Jamboree Hall—this was in the late forties, early fifties. Friday nights they would have all-black dances, and great blues bands would play. Saturday nights would be all-country.

Tommy X Hancock The original Cotton Club went back to the forties. It used to bring in all the big bands, like Benny Goodman and Harry James. The main reason it got so many big-name bands was that it was the only place between Dallas and L.A. that could seat 1,600 people.

Charlene Hancock When we opened our place, it was 1965. Then it burned down about a year or two later. We rebuilt. Both incarnations were out on the edge of town, in the country. Tommy’s folks took care of running the place. Tommy did the booking, his dad ran the front, and his mom ran the concession, which was soft drinks. We had Hank Thompson and Bob Wills, Ray Price and Willie Nelson.

Tommy X Hancock Of course, the greatest shows were Little Richard, right after he married his drummer. All of the greatest bands in the country were there over a twenty-five- or thirty-year period.

Hughes The mid-fifties, the dawn of rock and roll—that’s when the Cotton Club was such a place. Little Richard and all those guys—black guys and white guys. Crowds would mix. Then, later, the hippies and bikers and the Unitarians and the college students could coexist and there was no fighting. We had no bouncers. It was all because of Tommy Hancock. He was doing the thing Willie got known for in Austin—peaceful coexistence. You didn’t have to beat up the hippies.

Conni Hancock There was this little viewing area upstairs, and they would let me go up there sometimes. I would sit and watch. It was all cowboys. And it was interesting that the cowboys from the different little towns had their own little styles. They would wear their crease in their hat a certain way. Some of them would tuck one side of their pants in the boot. Depending on how they dressed, you could tell whether they were from Post or Ralls or somewhere else.

Hughes Out here they don’t clap for you when you play music. If they like you, they get up and dance. And the little ones dance, and the old ones dance. We can just dance. We could dance when we were twelve real well.

Conni Hancock One thing I loved about the music scene in Lubbock when I was growing up is that people danced to every single song.

Tommy X Hancock I remember playing at dances and barn dances where you would play until one or two in the morning, and then someone would give you money to play another hour, and then another hour, and you might be there until five or six. People virtually danced all night. They worked hard and they played hard.

Hughes Lubbock was dry. These Mexican guys would come out there with big washtubs in their trunk full of beer and sell till they sold out. You brought your own bottle to all those dance clubs, or there were bootleggers. And they sold speed: They had a gallon jar of pills sitting on the damn bar.

Tommy X Hancock Lubbock was overflowing with musicians and bootleggers. And with the bootleggers there’s a subtle psychological feeling that you should drink all of your booze before you get caught with it. So it resulted in everybody drinking too much. And the drug of choice was Benzedrine, so everybody stayed awake and got drunker and drunker. It was just as rough and rowdy a scene as ever was. Lubbock’s a little like an Indian reservation—it’s a real easy place to get real bored. And so there was a lot of drug abuse.

Keys There was a place called Club 87 out on U.S. 87—I used to listen to a lot of music out there. Then, of course, the Glassarama. Then there were a few other after-hours joints that you would only go to if you wanted to get, you know, shot or stabbed or both.

Hughes When Elvis played the Cotton Club, he stood outside and bragged about sexual conquests. We’d never heard people talk that way. Girls would come up and let him sign their bra or their panties. We were hoping to see some panties for the first time; women were standing in a line. None of that had ever happened. Earlier on that tour Elvis got punched out in Wichita Falls and in Lubbock because guys were jealous. Their girlfriends were out having him sign their panties.

Juke A real important scene was Stubb’s Bar-B-Q. That came around in the seventies. Stevie Ray [Vaughan] played there; everybody played there.

Hughes Stubbs would open up and only serve maybe two customers in the day but stay open and let musicians come and play that night.

Terry Allen I remember in the seventies and early eighties, musicians who lived there could actually make a living playing music. Which is pretty odd for a place that size, but there were a lot of clubs. And then it all up and shut down and became discos or whatever.

Dying to Get Out

Ely I’m sure all of us were always trying to get out of there. When you grew up there, you realized that isn’t where you wanted to be, especially if you had actually gotten out of there and seen some of the world.

Jennings Buddy was up and gone very quick—he had to get out of there.

Keys Music was my only ticket out of town. I was a failure at crime, and that was about my only other option if I’d stayed in Lubbock. There were several of the policemen on duty there at that time who just did not like musicians at all, especially young ones hanging out late. And it was suggested by several cops that it’d be a good idea if I went someplace else. They suggested that to several other people too. So, thank you, Lubbock Police Department!

Odam I left there in sixty-eight. There wasn’t anything there left to do. It was just a town of retired farmers and ranchers and college students, and that’s it.

McLarty It was a great place to grow up and be from, but once you realized what was what, you were, like, “I’ve got to get thef—out of here.”

Traci Lamar Hancock It’s probably a great place to grow up, but I am glad that I got out of it when I did. Just in time. Because teenagers there are bored to death. There’s nothing to do but drink a lot.

Tommy X Hancock I hated it. I was a poor white trash kid in the Depression in a town that was having a drought. And not only was there nothing to do, but what there was to do was negative.

Jo Harvey Allen I was the first person in my family to ever leave. My grandfather was hanging on to a banister just bent over double and sobbing. And my whole family was wailing when Terry and I got into the car to drive off. It was just a dirge. We got in this black Ford and headed for L.A. and didn’t know one single person. I didn’t know anybody else who had done that.

Weiner People talk about the Austin music scene, but really, it’s Lubbock transferred to Austin in a lot of ways.

Tommy X Hancock When we moved to Austin, in 1980, there were already eleven working bands here from Lubbock that we knew about. They had a terrific support system.

Hughes I make jokes about the first guy who left Lubbock for Austin in 1911. He was a tuba player. He wrote his own tunes and couldn’t get along here because it’s too repressive.

Jennings I love Texas as much as anybody. I have the Texas flag in my living room here up on the wall. Only it’s upside down; that means I don’t want to live in West Texas anymore.

Terry Allen When I was growing up, I didn’t have a clue what I wanted to be. The only thing I knew that I liked to do was make pictures and play music. But the idea of it being something that you could do with your life—there was just no reinforcement for that. What happens is, you leave a place with a vengeance to get away from it to go find the world and find yourself and find what you want to do. And then running as far away from that stuff as you can, you realize that’s really where all your blood and history are. So you make a full circle and realize this endless resource to tap into in your work.

Jennings Lubbock is not a good place to try to get started, because there are really no outlets, but the good thing is—you’re not that influenced. As far as songwriting and styles, it’s a good place to develop your own style.

Pierce I know I would be different if I hadn’t grown up there.

Jo Harvey Allen There is just an amazing level of confidence in people from Lubbock. I remember seeing lots of people from that part of the country when I was living out in L.A. And I noticed that it seemed like everybody else I was meeting was on this quest to be something, or to achieve some great thing. And it seemed like everyone I knew in Lubbock already was whatever that was. It was good enough. It was sort of like, “Well, if I’m different and you don’t like it, well, that’s just tough. But this is who I am.”

Musical Genius

Hughes Before Buddy Holly, when I was in high school, you had to play football. You had to if you wanted to get any dates. And then Buddy Holly comes along. Here’s a skinny guy with a guitar—I mean, the whole damn world changed. Every skinny guy in New Jersey owed his first woman to Buddy Holly. And the football players didn’t get to beat you up.

Weiner When you’re talking about West Texas music, the most important musician is Tommy Hancock. Tommy is one of those people who does things on his own terms and in his own way. And he has remained true to himself and true to his family.

Fiel Of all the songwriters that came out of Lubbock, I don’t think there’s anybody who can match what [Angela Strehli’s brother] Al Strehli does. You feel something when you hear what he writes. It may not make sense to you, but you’ll feel something. That’s one of the things that makes a great song. If anybody around here ever was a musical genius—other than Buddy Holly—I’d say it’d be Al. Right now he’s up in Colorado, composing big choral pieces in some little old mountain cabin.

McLarty Bobby Keys is from Slaton, fifteen miles from Lubbock. He joined Buddy Knox in fifty-nine. And he told me that Jerry Allison went to Bobby’s grandfather and told him that it would be a good thing to let his grandson go on the road. So he went on the road, and he never went home. That guy’s history is amazing. I think he’s the only guy who can say he played with Elvis, the Beatles, the Stones, Stevie Wonder. He never played with Buddy Holly, but he used to go to their rehearsals, and they used to send him out to get Cokes and fries. They would say, “Go get us Coca Colas, boy.”

Hester Norman Petty is the one history hasn’t been kind to. I wouldn’t say he was an angel or anything, but I just feel like his contribution to the Crickets is understated. His vision was essential. That flame of music that was in Lubbock, Texas? Clovis, New Mexico, is where it got channeled.

Ely Curley Lawler, the greatest fiddler in the world. Don Baggett, one of the greatest guitar players I’ve ever heard. Eddie Beethoven, a great songwriter. And John Reed helped everybody organize music together. One of the guys that I used to love was a guy named Lucky Floyd. He had the best rock and roll band in town, the Sparkles. Gary P. Nunn played bass with him, and Jimmy Marriot played drums.

A Tough Damn Town

Hughes This is a tough damn town. Bob Dylan had to cancel, and Jerry Jeff has said several times, “I’ll never go there again”—although he does. We’re in the middle between Austin and Albuquerque and L.A., so bands want to play here, but you can never tell whether people are coming out or not. In fact, we have this new 15,000-seat United Spirit Arena, which just sold out for Elton John in two hours.

Terry Allen There are a lot of people in Lubbock who still play music. There are a lot of young musicians. It seems to me that the club thing kind of comes in cycles. Right now, I don’t even know of a place people can go to play.

Steve Maines The idea with the Depot District [the downtown entertainment area] was to create a little [Austin’s] Sixth Street. It’s going to take some time, but I think they’ll get it.

Weiner Where professional entertainment is scarce, you make your own entertainment. And I think that’s true today too—there are a lot of people playing here. New bands coming all the time.

Odam They are still a-comin’ out. Just like a chute in a rodeo. Comin’ out of chute number one.