“Everything that can ever happen in life goes on in a hotel. You have mystery, sex, crime, death. You see people at their best and at their worst. There are celebrities and petty thieves. Duchesses and whores. You know who’s sleeping with whom—people’s darkest secrets. A grand hotel is not just mortar and bricks but a living, breathing thing.”

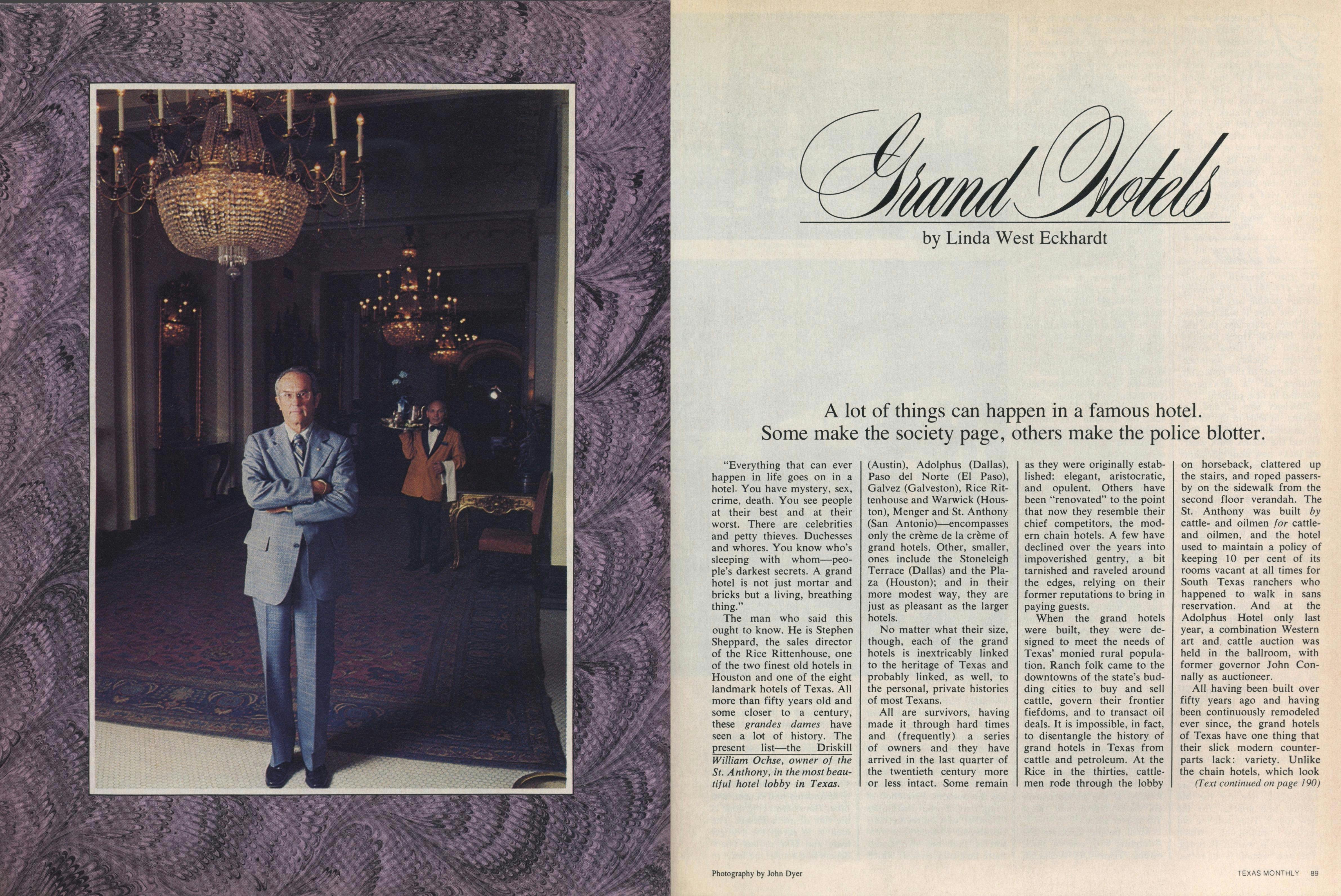

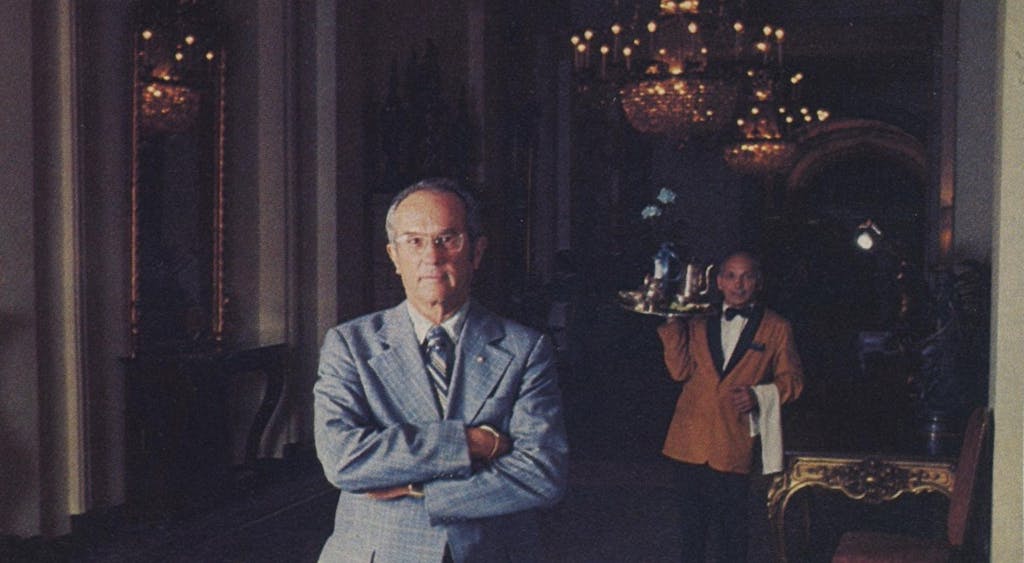

The man who said this ought to know. He is Stephen Sheppard, the sales director of the Rice Rittenhouse, one of the two finest old hotels in Houston and one of the eight landmark hotels of Texas. All more than fifty years old and some closer to a century, these grandes dames have seen a lot of history. The present list—the Driskill (Austin), Adolphus (Dallas), Paso del Norte (El Paso), Galvez (Galveston), Rice Rittenhouse and Warwick (Houston), Menger and St. Anthony (San Antonio)—encompasses only the crème de la crème of grand hotels. Other, smaller, ones include the Stoneleigh Terrace (Dallas) and the Plaza (Houston); and in their more modest way, they are just as pleasant as the larger hotels.

No matter what their size, though, each of the grand hotels is inextricably linked to the heritage of Texas and probably linked, as well, to the personal, private histories of most Texans.

All are survivors, having made it through hard times and (frequently) a series of owners and they have arrived in the last quarter of the twentieth century more or less intact. Some remain as they were originally established: elegant, aristocratic, and opulent. Others have been “renovated” to the point that now they resemble their chief competitors, the modern chain hotels. A few have declined over the years into impoverished gentry, a bit tarnished and raveled around the edges, relying on their former reputations to bring in paying guests.

When the grand hotels were built, they were designed to meet the needs of Texas’ monied rural population. Ranch folk came to the downtowns of the state’s budding cities to buy and sell cattle, govern their frontier fiefdoms, and to transact oil deals. It is impossible, in fact, to disentangle the history of grand hotels in Texas from cattle and petroleum. At the Rice in the thirties, cattlemen rode through the lobby on horseback, clattered up the stairs, and roped passers-by on the sidewalk from the second floor verandah. The St. Anthony was built by cattle- and oilmen for cattle- and oilmen, and the hotel used to maintain a policy of keeping 10 per cent of its rooms vacant at all times for South Texas ranchers who happened to walk in sans reservation. And at the Adolphus Hotel only last year, a combination Western art and cattle auction was held in the ballroom, with former governor John Connally as auctioneer.

All having been built over fifty years ago and having been continuously remodeled ever since, the grand hotels of Texas have one thing that their slick modem counterparts lack: variety. Unlike the chain hotels, which look like they were cloned, the grand hotels have something for everybody. Want a little parlor with a Victorian loveseat? They’ve got one. How about a king-sized bed with red velvet spread and cupids on the headboard? Ask. Do you go back to Lucy and Desi twin-bed days? Take your pick of several. In some of the old hotels even the corridors from floor to floor are different.

There is also tremendous variation in the quality of rooms simply because most hotels of this age are in a constant state of renovation, usually from the top down. The higher the floor, the better the units. Some are utterly charming, others are real losers with lousy beds and a sorry view. As might be expected, the second-rate rooms cost less, but they don’t really do justice to the potential of the hotel. It’s a mistake to try to go budget class in older hotels, particularly considering that they almost always have other rooms available because of their lower occupancy rate. Then, too, most of them quietly keep a clutch of rooms empty in case of emergencies and the unexpected arrival of VIPs. It may take looking at several rooms to find one you really like, but in the end, at an older hotel, it will be worth it.

Staying at a grand hotel involves services, customs, and protocol that you may have forgotten existed. If you grew up in the Howard Johnson generation, you may not have even heard of them. Some, like valet service for quick washing and dry cleaning, are great. Others, like tipping for every minuscule favor, are not so great. But they’re there if you want them.

Room service breakfast is one of the luxuries still available in a grand hotel that you shouldn’t deny yourself. Opportunities for pure self-indulgence are too rare to miss. As always, though, there are different levels of quality. The cheapskates bring your already cooling scrambled eggs and toast on a flat, unadorned tray and have to go back because they forgot the orange juice. First-class operations bring the meal on a warming cart with white tablecloth, real silverware, and a generous pot of steaming coffee.

Porter service, another luxury, does have the aforementioned drawback—tipping—and to put it mildly, tipping can be expensive. At the Rice, the doorman took my bags from the car trunk, set them on the curb, and held out his hand. A bellman carried them upstairs and stuck out his hand. In five minutes at 25 cents a bag, I had spent $3. Finally I decided to do like Jimmy Carter and carry my own. Forget decorum.

Valet parking is another mixed blessing. You don’t have to park the vehicle yourself, but you do have to pay. The average charge per day is $2.50. Any hotelman will quickly assure you that there isn’t free parking at a motel either—it’s just built into the room rate. Somehow, though, it’s less painful when buried in a single charge.

But these are minor irritations. When compared to the small daily luxuries like maid service, deference from the staff, and the subconscious feeling that you’re living in Upstairs Downstairs, all aggravations disappear. Some people are so seduced by the aura of a grand hotel that they never leave. These “permanent guests” generally fall into one of two categories not mutually exclusive: rich and/or old.

Older persons live in hotels because they are tired of hassling with household chores and find a hotel more palatable than a retirement home or moving in with their grown children.

The very wealthy live in hotels strictly for convenience. Two of these—a couple with the unlikely names of Freddie and Top Norris (she’s Freddie, he’s Top)—moved from Dallas to Houston last year and checked into the Warwick—indefinitely. Top, an independent oil operator, has even given up his office and now does business exclusively at the Warwick. He remarks, “I only deal with chairmen of the board and such like that, and what could be better than the Warwick for doing business with those folks?”

Freddie answers the door to their apartment, which probably costs $4000 a month, wearing a ladies’ tuxedo with a white flower at the neck and black suede spring-o-lators. According to her, “Everything is just great. I can’t find anything wrong with the Warwick.” And indeed, their apartment is sumptuous: French antiques, fine rugs and paintings—all belonging to the Warwick. The only personal thing of the Norrises in evidence is one small stack of Fortune magazines in an otherwise empty, cavernous bookcase.

There are, however, hotel guests who are even wealthier than most of the permanents. Middle Eastern sheiks who come to Houston on oil business sometimes rent an entire floor of the Warwick. They don’t need all the rooms; they just like the privacy. One night when a group of them was due to arrive late, the hotel’s French chef made a point of staying late too, ready to concoct some fancy middle-of-the-night Mid-Eastern cuisine. Sure enough, the room service phone rang shortly after they’d checked in. They ordered hamburgers all around with mounds of french fries and don’t forget the ketchup.

Movie stars who stay at grand hotels want good service, too, but they also want privacy. When Frank Sinatra stops at the Warwick, he provides his own retinue of Sicilian companions. Business moguls in town to close a hot deal frequently seclude themselves in hotel suites for days, calling in local entrepreneurs to conduct their affairs in the privacy of the hotel’s unseeing gaze.

James Cazanas, until recently the owner of the Rice Rittenhouse, explains the psychology of the ploy. “In a business deal, you invite the men into your suite for drinks or dinner. Then they’re in your territory and it turns the advantage your way.” One of Cazanas’ primary motivations in purchasing the Rice was to create the complete business executive’s hotel.

It could be said, in fact, that the mainstay of grand hotels today is business, in one form or another. Regardless of their other customers—corporate, tourist, or walk-in—business conventions are the financial backbone of grand hotels. The reasons for this are obvious: because of when they were built, these hotels frequently have larger public areas, lower rates, and more accessible downtown locations.

When it comes to conventions, the hotel will make considerable concessions to get the bid. Rooms are sold in blocks, and as much as 85 per cent of the total hotel space may be promised. Rates are sometimes reduced for a guarantee of a full house. For enormous gatherings that use a city’s convention center, the nearest hotel usually gets first shot at them.

Although hotelmen realize that conventions are their bread and butter, they know that conventioneers are not repeaters. Thus, a convention delegate is not likely to be treated with as much solicitude as a corporate executive who rents a junior suite once a month. In fact, there is such a difference in the way VIPs and walk-ins are treated that it would almost seem worth the gamble to try to pass yourself off as a biggie. For instance, celebrities are sometimes offered free suites in an unspoken agreement that the hotel may later use their names for publicity. You know: Bud Big Shot Slept Here. Hotels also realize that a good word, or a bad one, from certain dignitaries can materially affect their future business. Accordingly, the hotel’s public relations department does everything in its power to make the big shot’s stay as pleasant as possible. When George Wallace visited the Adolphus in Dallas, word came down that he liked Baby Ruth candy bars. The hotel immediately provided cases of them (the first of which was devoured by the Secret Service men who preceded Wallace into the hotel).

Visiting dignitaries, whatever furor they cause, are at worst an intermittent source of problems. The bulk of the difficulties a hotelman faces are on a day-to-day basis, and not the least of them is prostitution. Here hotels often find themselves in an awkward position. Although they’ve never been known to require marriage licenses of people checking in, they do feel some obligation to protect their guests, even if it’s from themselves. One security chief calls this part of his job “coaching.” If he sees a hotel guest in the bar with a known streetwalker he may call him aside and remind him that these girls, who usually work in pairs, are notorious for rolling guests and relieving them of their more portable worldly possessions. According to Randy Linn, formerly with the Adolphus, nine times out of ten the guest will tell the girl to hit the road. If streetwalkers are found working a hotel, they are normally escorted to the door at once.

Hotels do make a distinction, however, between streetwalkers and call girls. A call girl, obtained through more circuitous routes and charging a higher fee, most likely comes through the front door on the arm of her escort for the evening, and the hotel looks the other way.

A common belief about hotels, historic and otherwise, is that to find overnight companionship all you have to do is mention your desire to the bell captain or elevator operator. This practice is not officially condoned by the management of Texas’ grand hotels, and in the past, employees found procuring for guests have been dismissed—which does not rule out the possibility of a little freelance procurement going on without management’s knowledge. As a general rule, though, only at less prestigious hotels is this particular service part of the routine.

As you might predict, crime in a hotel runs the gamut: everything from a police shootout at the Rice-Rittenhouse this January (which left a prominent Houstonian dead in an alleged drug ring-porno film operation) to what is known in the trade as mom-and-pop fights. Usually, in cases like these, the hotel is merely an innocent bystander, but occasionally the hotel itself is a victim. In 1974 one of Texas’ grand hotels found itself minus several nights’ rent when two phony aristocrats moved in and started using the hotel as headquarters for a con game involving local businessmen. The pair was charged with theft of services and defrauding an innkeeper, but they left town and haven’t been seen or heard from since.

Crime directed at hotels, or their guests, is also the reason that you won’t find many hotel keys marked “drop in any mail box” any more. They’ve started leaving the hotel’s name off in order to discourage thieves who search airport trashcans for discarded keys, then discreetly let themselves into the rooms.

Theft and fraud aren’t the only financial headaches that grand hotels have to contend with. Cost of operation is climbing steadily and owners say if they passed along cost increases as they occur, their hotels would soon be empty. Thus they must constantly find ways to cut expenses in order to maintain a decent profit margin. Utilities, for example, are up over 300 per cent in three years. The Driskill’s July 1976 electricity bill ran $16,000, the Adolphus’ $30,000, and the Galvez’ $15,000.

Utilities are a large expense, one of the largest, but little things eat away at profits as surely as big ones. Within the next few years, you’ll notice that all of those handy free ice dispensers have disappeared from hotels (and motels). In their place will stand coin-operated machines that dispense one bucket of ice for a quarter. But don’t think the hotels will be making a killing selling ice. The new machines cost $4000 each and they’re being installed purely for health reasons. The 1970 federal Occupational Safety Health Act (OSHA) prohibits open ice bins because they’re unsanitary. It was discovered that they were being used for many things besides the dispensing of ice. Guests have, for instance, stored Limburger cheese in them, spilled milk in them, and on one occasion, iced down a recently deceased dog in one of our finer hotels.

Monetary considerations also help explain why good food in a hotel is, unfortunately, the exception rather than the rule. A big reason is plain old profit. According to Gerald Sill, president of the Warwick, “The bottom line profit is higher, percentage-wise, in a hotel where there is more money coming in from rooms and less from food and beverages.” There is generally a 50 per cent profit on rooms and at best a 20 to 25 per cent profit on food. The few hotels like the St. Anthony, Warwick, and Rice that do emphasize food are hoping to lure and hold a discriminating business executive clientele who will spend most of their time and money in the hotel.

Keeping guests happy and in the hotel is important because, on the average, hotel managers report that each guest will “drop” an amount of money for services equal to the cost of his room. That means that an average spender with a double room costing $35 (a good bet for any downtown hotel, old or new), will spend another $35 per day during the stay for tips, parking, meals, drinks, and other amenities. Most guests average a stay of two and a half days, which can easily mean a bill of $160 per person. It becomes obvious why downtown hotels cater to businessmen traveling on expense accounts or attending conventions where the firm picks up part of the tab. They are simply too expensive for most couples or families to consider for a vacation.

Most of the grand hotels in Texas have changed ownership within the last five years. New owners of grand hotels in Texas come overwhelmingly from one source—real estate development. And the reason they’re into old hotels is money. It’s cheaper to renovate than to build, and room rates can be held to a competitive edge that makes Hyatt owners (who usually spend millions each year just on debt service) sweat. The Adolphus, Paso del Norte, and St. Anthony are all currently owned by real estate developers and until February of this year so was the Rice Rittenhouse.

It doesn’t take a very sharp pencil to figure out what the attraction is. William Ochse, owner of the St. Anthony, who plans to build a new St. Anthony tower, expects to pay $50,000 per room for the new construction. Old hotels can usually be bought for sums in the neighborhood of $10,000 per room, which, of course, includes the lobby and all the other public rooms in the facility. Chris Cummings paid $2 million for the 141-room Paso del Norte two years ago, after it had been completely renovated. He is managing to make further improvements from revenues that the hotel produces. James Cazanas paid $6 million for the 650-room Rice, planning to double that investment in improvements, to bring the cost per room to about $20,000, which was still less than half the price of new construction in Houston. Alan Tremain, president of Hotels of Distinction, told Business Week, “Investors are after the classics, with elegance, spacious rooms, the sort of panache that sophisticated business travelers appreciate and that can be translated into higher room rates.”

Even with their lower initial costs and a favorable attitude from the public, grand hotels sometimes prove to be risky ventures. A look at the record of hotels in Texas shows that the schemers and dreamers who get into this business sometimes bite off more than they can chew. Most of Texas’ grand hotels have been on the edge of bankruptcy more than once, and most have been closed at one time or another. The story of the Rice Rittenhouse is typical of what can happen when things don’t go right. For James Cazanas, former owner, the gamble of buying a neglected grand hotel failed. He made two fatal errors—undercapitalization and failure to get the local financial community behind him. The result was chapter 11 bankruptcy for the hotel corporation.

Economics—even when it goes right—doesn’t satisfactorily explain why businessmen get involved with grand hotels. Obviously there’s more in it than money, and regardless of the headaches, those who buy and work in a grand hotel are hooked as surely as heroin addicts. To a man, they say it isn’t a profession but an affliction. Put a hotel manager with a Hilton background into an independently owned historic hotel and his ordinary business acumen turns into religious zeal.

Put in the most basic terms, the appeal of a grand hotel is psychological, and it can be understood by the peculiar usage, among hotelmen, of one word: she. A hotel is a woman. She may be a granny, she may be a girl, but whatever else she is, her identity is undeniably female. In his book The Driskill Hotel, Joe Frantz calls that hotel “A sort of Mother Hotel where the children of Texas ‘come home’ for all the myriad purposes and ambitions and undercuttings that draw big families together.” Gerald Sill, president of the Warwick, thinks of his hotel not as a grand old lady but as a bionic woman who’s had her internal organs replaced with gleaming stainless steel parts.

When he decided to buy the Rice Hotel, James Cazanas phoned his wife and told her, “I’ve fallen in love with another woman.” His fantasy is very detailed. “Take a mature lady, Zsa Zsa Gabor—in a Chanel suit, her hair styled. She has a sophistication, a worldliness that makes her so much more interesting than a sixteen-year-old. It’s much sexier.”

And he may be right. If gender is figurative as well as factual, if it is something that’s conveyed by feeling and ambience, if it’s something that is enhanced rather than diminished by the years, then the Rice Rittenhouse and her sisters are indeed the grand old ladies of Texas.

Staying in a downtown hotel makes you acutely aware of the heartbeat of a city, especially after dark. Austin throbs with the sound of music in the night air. Houston screams with sirens and squealing brakes. Dallas is unearthly quiet because it is abandoned after 5 p.m. You get to know a city, its ebbs and flows, its pigeons, its typical characters, and its inevitable derelicts. If you plan to visit a major Texas city this year, here’s what to expect from its grand hotels.

The Driskill

117 East Seventh, Austin/ (512) 474-5911/ 189 rooms/ average double rate $41

At the time it was remodeled three years ago, the historic Driskill Hotel inspired a poem by a fond Austin Heritage Society member, who referred to the venerable building as “a dowager—splendid in new raiment.” Dowager she is, and her raiment, at least in the lobby, is undeniably splendid. But behind the scenes she’s wearing tacky new undergarments that hardly go with the dignity that should accrue to a lady of more than ninety-two years. Until 1974, the Driskill was a fairly down-at-the-heels old hotel, but one with a lot of history. Then Braniff Airlines bought the place and employed an architect from Munich to redo the lobby and the dining room and to create and decorate a posh disco in one corner of the downstairs. At the same time, the rooms were redone, but not by the architect. Two million dollars later the owners had a sumptuous, modishly decadent movie set of a hotel—downstairs. But all you have to do is get on a mirrored elevator and ascend to the upper floors and the coach turns into the pumpkin of a pure chain hotel. Identical drapes, bedspreads, and carpets are in almost every cubicle. Basically there are two styles, one for the old section and another for the new tower. They call the old section traditional, which translates as walnut Formica. The new section is all tufted black plastic headboards and black plastic cube tables. It’s a far cry from the days of Uncle Bob Kleberg’s permanent suite with its specially built, oversized ball-and-claw mahogany chairs and green plush carpets. The sad thing is that before Braniff bought it, the previous owners auctioned off a hotel full of antiques—and all the ghosts that went with them.

Not everyone objects to the sameness of the rooms, though. One twenty-year customer says that the hotel is better now, that the cooling and heating are better regulated, and that it’s more comfortable. Many rooms still lack individual controls, however. Mine was so cold that the only way I could warm up was to get into a tub of hot water.

One of the good things about the new Driskill is its stylish dining room. It has been known to put out superb seafood and beef, though of late the food has not been particularly impressive.

Copying from Eastern hotels, the Driskill has moved its bar to the lobby, adding a pianist to bring in the five o’clock crowd.

The Cabaret is a jumping discotheque where almost-too-tired businessmen go looking for companionship.

The Adolphus

1321 Commerce, Dallas/ (214) 747-6411/ 865 rooms/ double rate $22-$30

In Bonnie and Clyde, Warren Beatty asks Faye Dunaway, a waitress from West Texas, “Now how you like to go walkin’ in the dining room of the Adolphus Hotel in Dallas wearing a nice silk dress and have everybody waiting on you?” Which goes to show that the Adolphus is legendary.

Built in 1912, the hotel was the grand dream of Adolphus Busch, a beer baron from Saint Louis, who put a beer bottle motif on the turret and had hops incorporated into the ballroom frescos. It has served travelers from North and West Texas ever since.

Most people associate the Adolphus with one of three events: Texas-OU Weekend, the State Fair, or the Cotton Bowl. But under its present owner, Leo Corrigan, Jr., it is first and foremost a convention hotel. Located at Akard and Commerce, a corner which it shares with the Baker Hotel, the hostelry has the dubious distinction of being part of what the Dallas Chamber of Commerce calls Cornbread Corner. The reason is that the two hotels there host conventions which are less grandiose than those to be found at the newer and finer Fairmont.

Rooms at the Adolphus vary from A-l to Awful, but it is, like most hotels, in a constant state of renovation, The twentieth floor is newly remodeled and decent, and other floors are being done at the rate of one a month. The idea is to scrap the Naugahyde and fake crystal chandeliers and return the hotel to its former glory. The major work will be done on the sixth to the fifteenth floors.

Leo Corrigan, Sr., who bought the hotel in 1946, was a wheeler-dealer, but he never forgot his Bible Belt background. On the fourteenth floor he installed a chapel, which hotel guests may still use, if they feel in need of spiritual guidance or want a wedding in a hurry.

Rumor has it that the younger Corrigan is trying to sell the Adolphus. With occupancy running between 45 and 50 per cent, resident manager Grant Baere admits the hotel sometimes loses money, but feels the remodeling could put the Adolphus back on the map. With the opening next year of the Hyatt Regency in Woodbine Development’s Reunion project, the Adolphus will need all the help it can get.

The Paso del Norte

115 S. El Paso, El Paso/ (915) 533-2421/ 141 rooms/ average double rate $25

If a gambler’s instincts were ever needed to make it in the hotel business, the time is now at the Paso del Norte. Magnificently renovated, the Paso is served by a faithful staff, some of whom have worked there for fifty years, and is located close to the convention center in a city that has 360 days of sunshine per year.

But the odds are formidable. Overall, El Paso has too few hotel rooms to attract the really big conventions and not enough big industry to provide a sizeable corporate trade.

Chris Cummings, a self- made real estate developer, bought the hotel for $2 million in 1975. According to him, the Paso is now breaking even. The over-all occupancy rate runs 55 per cent, up from a shaky 33 per cent in the spring of 1976. Seventy-five per cent of the hotel’s business comes from conventions. Tourists from Mexico are frequent guests.

The lobby of the Paso del Norte is one of the most beautiful in the state. The ceiling, a spectacular stained-glass dome designed by Tiffany himself and measuring 24 feet in diameter, is so breathtaking that it defies description. Legend has it that million-dollar cattle deals were sealed with a handshake and a toast of bourbon and branchwater under this dome, and it’s easy to believe.

The Paso has some of the most attractive rates to be found among grand hotels in the state. From $17 and up for a single, you can get a well-decorated room in bright clear colors with a gaily painted ceiling fan, good quality art prints, and antique furnishings. The glass in the windows is old and bubbly. The eighth and ninth floors, with raspberry striped wallpaper in the halls, are especially nice.

The presence of Juárez, just across the river, gives the hotel a Casbah aura that makes it exciting.

The Galvez

Twenty-first and Seawall, Galveston/ (713) 765-7721/ 50 rooms/ double rate $28

The Galvez is the only grand hotel in Texas designed and maintained as a resort. Although its classic Spanish facade is as impressive now is it was when it was built in 1911, if you look closely you’ll see that the old gal needs a new wardrobe and could stand to hire a cleaning crew.

Since April 1, 1971, the hotel has been owned by Harvey O. McCarty, a department store mogul of Rock Island, Illinois, and Dr. Leon Bromberg, an elderly Galveston physician. The finances of keeping the hotel open have been somewhat like pouring sand through a sieve, and rumor in the trade has it that they’d sell if the right party came along.

Charles Maurins, a Latvian hotelkeeper, has fought the good fight at the Galvez for five wearying years, struggling within the impossible limitations of a three-month tourist season and a twelve-month payroll. During the season the hotel maintains an impressive 85 per cent occupancy, but off-season it shrinks to an alarming 20 per cent. Maurins has increased his on-season period to five months by aggressively soliciting conventions (the hotel has the city’s largest public rooms and is next door to the convention center), but needs seven to make the hotel a black-ink operation.

The signs of benign neglect are everywhere. An underground hallway leading to the swimming pool looks like the hall in a charity hospital. In fact there is an aura of World War I hospital to the whole place—an odd musty smell.

I kept expecting to run into Lady Brett in the hall.

The lobby of the Galvez is great to prowl around if you’re in a sort of Grand Funk mood and want to imagine what it must have been like in its heyday. The rooms are spacious, but the furniture is overdue for replacement, and unless you want to induce a case of serious depression, you should definitely request a room with a view of the Gulf.

Why do people come to the Galvez? According to assistant manager Dennis Trahan, a Mississippian, “People want service. They want their bags carried and ice delivered.” Despite everything else, you do get service at the Galvez and that, combined with the beach and the sun, may be enough.

The Rice Rittenhouse

917 Texas Avenue, Houston/ (713) 227-2111/ 650 rooms/ average double rate $36

Probably the most uncertain future in hotels in Texas today is that of the Rice Rittenhouse, at least insofar as its finances and future ownership go. At the moment the hotel corporation is bankrupt, but recovering nicely, and former owner James Cazanas, who was responsible for the hotel’s recent renovation, is out of the picture.

When Cazanas appeared from New York City to save the Rice from impending destruction a year ago, he came with $6 million in hand. On January 15, 1976, he purchased the hotel from Rice University, et al. His business background was real estate, but according to a prominent New York City financier, “Mr. Cazanas does not have high visibility in the New York area.”

In his own words, Cazanas laid his estate on the line to buy the hotel, and his determination to succeed was formidable. He moved his family into the hotel, sans heat and light, and in seventeen weeks pulled together a renovation that would have taken anyone else seventeen months.

His wife Johann not only personally supervised the redecorating but also participated in the physical work it takes to put an old building in shape. She discovered the floor in the Flag Room, a stunning design in inlaid wood under layers of other flooring, and personally stripped and stained it. Two enormous chandeliers in the ballroom took Johann and helpers two weeks to clean.

While Cazanas owned the hotel, its look was substantially altered. Earth tones and Southwest motifs were overlaid on the existing structure to make the hotel an interesting blend of traditional and contemporary. Forty per cent of the hotel is newly remodeled and the redecorated rooms are very attractive.

Some people have complained because of the changes in the hotel’s traditional decor, but according to Johann, “We are preserving a landmark, and creating a new one. This is Houston, Texas. It is not Europe and it is not New York.” There’s a vibrancy to the hotel that you can feel as soon as you set foot in the lobby. Before they were set out on the sidewalk by a federal court, the Cazanas family gave the old Rice a shot of adrenaline. It will be interesting to see what happens next.

The Warwick

5701 Main, Houston/ (713) 526-1991/ 420 rooms/ average rate $52

The age of kings is dead—except at the Warwick. Purchased in 1962 by John W. Mecom, Sr., the Warwick was an old residential hotel that already had a reputation for having housed as many as sixty Houston millionaires at one time. Mecom, the third richest independent oil operator in the United States, started with that reputation and built on it.

In the same spirited way he tapped the ground for black gold, Mecom, with the help of his wife Mary Elizabeth, stripped European palaces of enough treasures to fill several museums and rebuilt the Warwick around the art. His strategy for attracting guests was equally daring. Mecom decided to ignore 90 per cent of the ordinary hotel’s clientele and go after the top 10 per cent, the very rich. The scheme worked. From the day it opened, the Warwick has consistently made money. Occupancy is 65 to 70 per cent.

The Warwick is the sort of place where filthy-rich Texas oilmen with Lucchese boots and bad grammar rub elbows with European peerage of impeccable lineage, and everybody’s happy about it. The powerful use the hotel as a home away from home.

If you have ever wondered how the super rich live, stay at the Warwick. Go with the attitude that your wish is their command (it is) but also be prepared to assert yourself. You’ll find that there is some undefined power quotient that must be reckoned with. Apparently, wealthy folks expect their help to be haughty because the initial manner of Warwick service personnel is arrogance. You can dispel this quickly, however, by speaking firmly and remembering that you, after all, are the guest. You’ll find their attitude will miraculously change to one of utmost care and concern for your welfare.

Room service here is like no other. So what if the eggs Benedict costs $5.50. It comes on a rolling table set with fine china and silver and a white tablecloth. There are fresh flowers, a pot of Scottish jam, and a room service waiter who is the soul of discretion.

As for convention business, the Warwick goes for boards of directors meetings, small professional symposia, and other select groups. As one independent oil operator beamed to me over breakfast in the hotel’s Cafe Vienna, “This here’s a good place to do mah oil and gas bidness.”

The Menger

204 Alamo Plaza, San Antonio/ (512) 223-4361/ 350 rooms/ double rate $22-$35

The venerable Menger, located next door to the Alamo, flourishes in spite of itself. Despite its marketing lassitude, the hotel maintains a remarkable 73 per cent occupancy, presumably because it is the best-known historic hotel in Texas. When Teddy Roosevelt recruited the Rough Riders in the famous old Menger Bar early in this century, the hotel got national press coverage that apparently hasn’t stopped. Travel agents dealing with out-of-staters find the Menger the hotel most asked for by tourists interested in history.

The Menger is unusual in that it has two lobbies—the new one (done in 1957), which adjoins a tropical patio, and the old one, which is all dusty oriental rugs and somber Empire sofas.

Charming rooms and suites may be had at the Menger, and there is a 110-room motor hotel addition to make traveling salesmen feel comfortable. In the old section you might get a canopied bed, a marble-topped dresser, or an antique rocker. But like the room Tennessee Williams described in his play The Eccentricities of a Nightingale, in it you may find “a sprinkle of light pink powder on the dresser, a hairpin on the carpet… an empty pint bottle of some inexpensive whiskey.”

Owned by Gal-Tex Hotel Corporation, a subsidiary of the Moody Foundation, the Menger’s business attitude is frustrating to San Antonians who consider the hotel a desirable place to take out-of-towners. The old bar, for example, frequently closes for reasons known only to God and the bartender, and simply does not open again until it’s ready.

If you like being where history happened, the Menger is the place, but be aware that history will be the best part of your stay.

The St. Anthony

300 East Travis, San Antonio/ (512) 227-4392/ 500 rooms/ average double rate $35

The St. Anthony, located across from historic Travis Park, has a slogan on billboards bordering San Antonio that says, “Only time can make a hotel this great.” Stay there and you’ll believe it.

Beginning with the state’s most beautiful lobby (which, inexplicably, is filled with plastic plants), the St. Anthony blends tradition with aggressive contemporary management to provide excellent service and rooms that are both tasteful and comfortable.

When R. W. Morrison bought the hotel in 1936 (twenty-seven years after it was built), his credo was that people would “come back to eat.” It’s true. Under the direction of Anthony Valdez, a spare 75-year-old chef, the hotel has maintained an excellent reputation for its food. The private St. Anthony Club is particularly well known for expert cuisine.

William Ochse, a supercharged real estate developer who says he sleeps only five hours a night, bought the hotel a little over six years ago, and the St. Anthony staff worried that he might make sweeping changes. But Ochse, like a wise Chinese overlord, instead kept everyone on, overlaid his personal management techniques on the staff, and produced a hotel that is better than ever. Occupancy is a very respectable 62 per cent.

Conventions are the mainstay of the St. Anthony, but the hotel also has a large walk-in transient business. There is little executive trade, though, because San Antonio is not a corporate center.

The St. Anthony is the kind of hotel presidents stay in when they visit the Alamo City. When Betty Ford came to town they cleared the tenth floor for her and gave her a corner suite, number 1082, which has a garden dining room, a formal European living room with a marble mantel, curio cabinets filled with porcelain figurines, velvet drapes, and a mirrored wall.

All the rooms aren’t of presidential caliber, of course, but there are hardly any bad rooms at the St. Anthony either. If you like a view, ask for the park side. Travis Park is lovely and to be able to see it from your room is well worth the couple of dollars extra it will cost you. If you go to the trouble of looking at several rooms, you can find one that is attractively custom-decorated. You’ll also get a phone in the bathroom, thick imprinted towels, and fine monogrammed woolen blankets on the bed.

On the top of the building is a roof garden, which is the hotel’s answer to a swimming pool. It looks like a Mexican patio and is a pleasant place to sun and relax. All in all, the St. Anthony is one of the finest hotels in Texas.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Longreads

- Hotels

- Crime

- Architecture