This promises to be a banner year for Texas flag buffs. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston has assembled an unprecedented exhibit of 32 Texas flags—from a tattered one that survived the Battle of San Jacinto to the huge ensign that flew over the battleship USS Texas— and the catalog is really a combination of breakthrough historical text and glossy coffee-table centerpiece. Given Texans’ staunch chauvinism and the nation’s newly rekindled pride in the Stars and Stripes, both the exhibit and the accompanying book should succeed with flying colors.

The study of flags is known as vexillology, from “vexillum,” a Latin word for a Roman cavalry flag. Although the discipline isn’t new, no one has ever before attempted to display so many historical Texas flags together or to write seriously about them at such length. Flags meant much more in olden days than they do now. The sight of our modern lone-star flag is so common—so woven into the fabric of Texas life—that we almost take it for granted. This exhibit’s faded declarations of loyalty—of silk, cotton, or wool, with crooked seams, lopsided stars, and unevenly lettered slogans—remind us not to. These vintage flags aren’t academic curiosities; they’re Texas’ equivalent of holy relics.

Many of the fragile cloths showcased in “Texas Flags, 1836-1945,” which runs through April 28, have never before been on public display. The gathering of the flags took five years and required the cooperation of eleven organizations, public and private. And Texas Flags, authored by Fort Worth historian Robert Maberry, Jr., is not just a history of Texas flags but a history of Texas through its flags, complete with bullet holes and blood—and minefields. In a state that revels in quibbling over such details as the exact number of Alamo defenders, an academic treatise on Texas flags is bound to offend some people—those, say, who have long believed that their ancestors or their hometown’s native sons designed, crafted, carried, or rescued various Texas flags.

For students of Texas vexillology (Tex-vex?), the bottom line is: Forget the phrase “six flags over Texas.” (We’re talking slogan here, not amusement park.) There were six nations that laid claim to Texas, but each of those countries flew more than one official flag; the number hoisted and the designs adopted varied according to royal affiliations, military actions, political loyalties, or personal whim. Over the nearly five centuries of Texas’ recorded history, in fact, its ruling nations seem to have changed flags more often than its residents changed underwear.

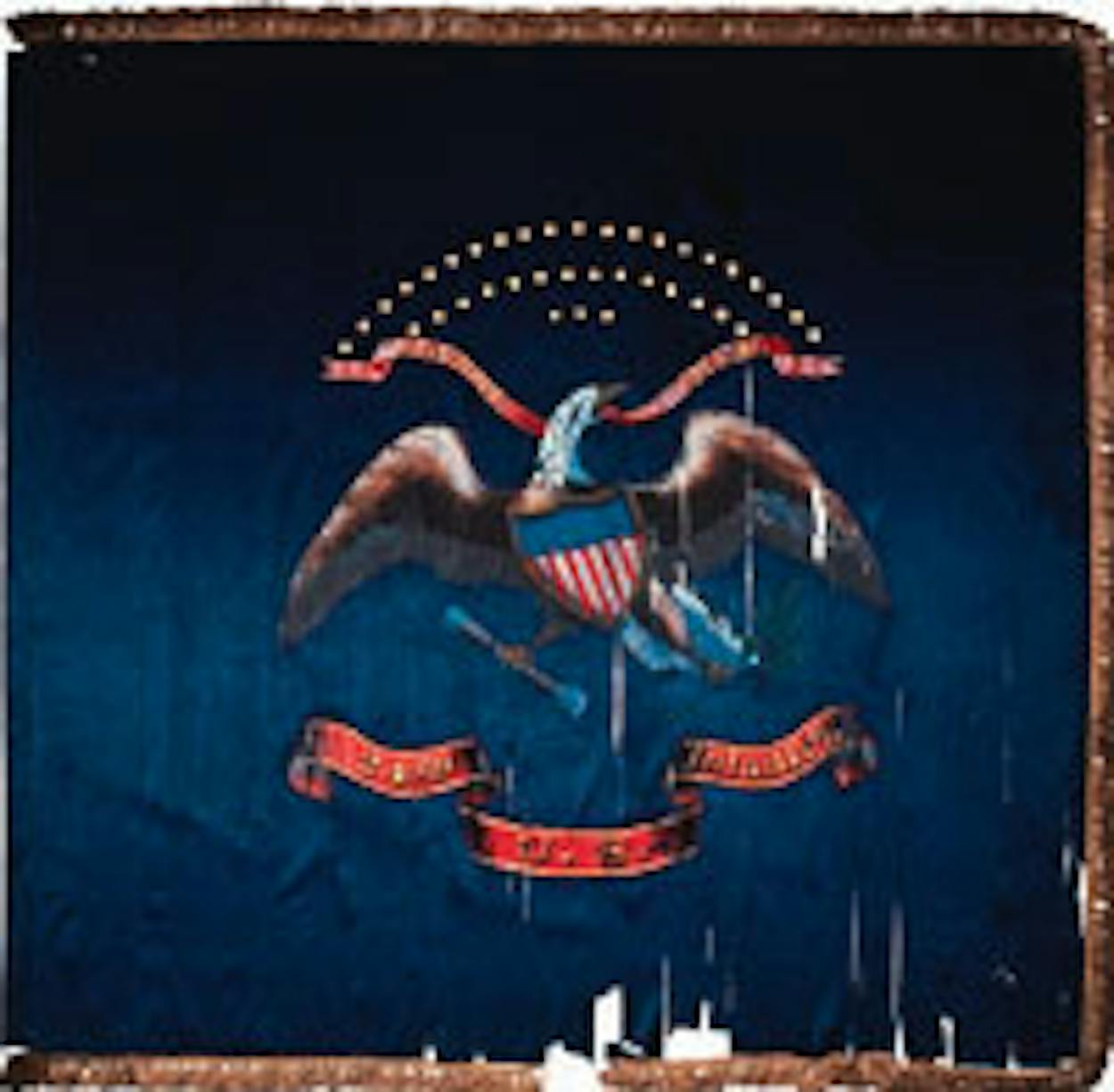

Spain, for example, is generally represented in the six-flags pantheon by the castles-and-lions banner, which is delightfully old-world. But the actual flag flown over what is now Texas probably had a plain yellow field with a red Burgundy cross (essentially a big x). The Mexican flag, with its dramatic eagle-and-snake motif, was made with and without the cactus, and miscellaneous partisan banners included everything from the sacred (the Virgin of Guadalupe) to the profane (a skull and crossbones). The design of the Stars and Stripes also varied, as more and more states joined the Union.

The Texas Revolution too was fought under scads of flags; every settlement or military unit patched together its own banner. I’ve always been partial to the Gonzales flag, which showed, on a white field, the black silhouette of a cannon that the Mexican army wanted to recapture, along with the nose-thumbing slogan, “Come and Take It.” The burning vexillological issue of the era, though, concerns (what else?) the Alamo. What flag flew over the doomed fort? Was it a version of the Mexican tricolor? The idea may sound absurd, but the sight of an outdated national banner or a regional Mexican flag would definitely have ticked off General Santa Anna, a dictator who had severely curtailed his people’s civil liberties. Or was the Alamo flag the banner of the New Orleans Greys, a group of brave volunteers? Neither, Maberry concludes, would have inspired William Barret Travis to write, “. . . our flag still waves proudly from the walls.” (So what did? Hey, read the book.)

Few flags survived the revolution. A rare exception—and the jewel of the Houston show—is one carried by the company of Lieutenant Colonel Sidney Sherman at the Battle of San Jacinto. It depicts a woman, the personification of Liberty, brandishing a sword. (She also has one breast exposed; can you imagine how that would go over today?) Now not much more than a handful of silk shreds, it is undeniably affecting. The exhibit has three other revolutionary-era flags, but they are all trophies from conquered Mexican battalions. Similarly, Mexico still possesses the fabled New Orleans Greys banner. Some Texans are infuriated that Mexico has repeatedly refused to return it, but according to attorney Charles A. Spain, of Houston, a longtime flag historian, “Under international law of war, we have no right to ask for it back. And no one ever suggests that we give back the battalion flags.”

Another vexing vexillological issue: How long has the lone star represented Texas? Arguably a Long time—an expedition to Texas mounted in 1819 by James Long, of Mississippi, may have flown a flag with the U.S.’s familiar red and white stripes and a single large star on a red canton, or corner. The Gonzales flag may also have had a lone star. But as historian Spain points out, “Without an actual physical flag, such speculations don’t amount to a hill of beans. Everyone wanted to have made the first lone-star flag, but where’s the proof?” In the first-flag sweepstakes, he theorizes, some retroactive starring likely occurred.

During the almost ten years that Texas was a republic, citizens continued to dither over flag design. One proposal for a national standard was simple and elegant, merely a gold star on a blue field; another was practically psychedelic, with blocks of horizontal Old Glory stripes and vertical Mexican-flag stripes, plus a mini-English Union Jack. A third proposal incorporated a rainbow (suggested, perhaps, by Roy G. Biv?). But relatively quickly, in 1839, the fledgling government adopted the design we use today. Back then folks didn’t care which stripe was uppermost, though the Republic of Texas Congress mandated that the white should be on top. To help you remember, I offer a line I learned way back in elementary school: “Cream rises to the top.”

Author Maberry is not above relating the romantic twaddle that has inevitably woven itself into flag tales. Consider, for example, the Betsy Rosses of Texas. One was a lieutenant’s wife, Sarah Dodson, of Harrisburg, who some claim was the first to sew a lone-star flag, in 1835. That same year a Georgia teenager, Joanna Troutman, sent a handmade lone-star banner to Texas with a group of volunteers from her state. Then again, maybe our Betsy was a boy: Charles Stewart, whom Maberry doesn’t mention, is revered by Montgomery County residents as the first to design the lone-star flag. There were also plenty of Civil War Betsies, including Fannie Wigfall, of Marshall, who supposedly sacrificed her wedding dress to help make a Texas flag for local volunteers. Some sources claim she made three, prompting Maberry to write, “While it is unrecorded how copious a woman she was, it is doubtful her dress could have been large enough to supply the silk for two more flags.”

The stories behind Texas’ Confederacy-era flags, which make up half of the museum exhibit, are what really set Maberry’s heart aflutter. His lengthy narration of the War Between the States is ambitious, thorough, and fun. He tells us that by 1860 the lone star had become a symbol of secession, representing not just Texas but any state choosing to stand apart from the Union, and mentions only-in-Texas oddities like the secession banner that flew over the Capitol, a gargantuan sixty- by twenty-foot flag that rippled and snapped atop a 130-foot pole. A great oops moment: The Confederacy had to replace its largely white “Stainless Banner” because, on a windless day, it appeared to be the venerable symbol of surrender. And Maberry loves the flowery speech of such luminaries as Jefferson Davis: “Texans! The troops from other states have their reputations to gain, but the sons of the defenders of the Alamo have theirs to maintain.”

The Civil War section is the best part of Maberry’s book, but the remainder is readable and occasionally stirring. He is unabashedly revisionist; his chapter on frontier cavalry units focuses on the African American buffalo soldiers, for whose services, he asserts, “nineteenth-century white Texans were eternally ungrateful.” And he examines the Cult of the Flag, a patriotic movement that peaked between 1895 and 1910 and was devoted to popularizing the Stars and Stripes, in part to counteract the reverence shown by veterans of the “Lost Cause” for their Confederate flags. The “old glorification” sparked a revival of interest in the Texas state flag as well, and Texas’ approaching centennial fanned the fire. My favorite flag-fever fact: In 1933 the Legislature standardized the design so “pupils in the lower grades of elementary school will be able to draw or make the flag.”

Maberry’s book isn’t perfect. For one thing, he completely omits mention of the French flag. Granted, that nation had only a flimsy and short-lived claim to Texas, but still. He counts the regimental colors of Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders as a Texas flag but leaves out other colorful candidates, such as the flag of the Republic of Cartagena, in what is now Venezuela, which was hoisted by the pirate Jean Lafitte when he commandeered Galveston Island from 1817 to 1820. And though the Houston exhibit contains two World War II flags, Maberry ends his text in the thirties. I would have enjoyed reading an analysis of the current Confederate battle flag controversy and an examination of the Legislature’s increasingly liberal flag-desecration laws, presumably to facilitate the production of such loyalist kitsch as lone-star running shorts and, as historian Spain writes in one of his essays, to “validate the practice of displaying a huge Texas flag on the field at football games played by the University of Texas at Austin.” So here’s an idea, Mr. Maberry: Texas Flags, Part Two. Let’s run it up the flagpole and see who salutes.

- More About:

- Art

- Houston Texans

- Houston