It was a game I played when I was little and wasn’t allowed to be outside while my father was working in the yard. I remember watching him from the front window and then following him from window to window inside our small house as he pushed the mower to the backyard, around the bougainvilleas, then the ebony, then the orange tree, disappearing for a moment behind the grapefruit tree, then reappearing next to the mesquite and his work truck. I used to knock on the windowpane when he was close by, but after a while I realized the machine was too loud and he probably wasn’t going to look up, considering how intent he was in maintaining the razor-sharp lines across the lawn. Still, I followed him, just in case. My father didn’t have the biggest house on the block or the newest car in the driveway, but he did have a yard he took care of every week, and somehow, when he was plowing one way and then another under that merciless South Texas sun, this seemed to be enough for him.

Other than watching the Astros lose, my father had no real hobbies. The yard was it. After mowing he would kneel down on a rectangular strip of carpet and cleave the grass along the edge of the sidewalk leading from the street to the front porch with a fourteen-inch knife. Then he’d do the grass along the curb. To him, the world was divided into two kinds of people: those who took care of their own property and those who hired other people to take care of their property. For a man who owned one suit and had few occasions to wear it, the yard was a chance to present another part of himself, if only to those neighbors who happened to drive by and admire his work.

One day when I was seven years old a man named Jose Angel came to our back door asking if there was any yard work he could do. He had just crossed over from Mexico and was hoping to send money back to his family. My father invited him inside to eat lunch, and the man sat on the edge of his chair in the kitchen, his face up close to the plate, the fork clutched in his fist as though it were a twig he’d picked up in the yard. They didn’t talk until afterward, and this was mainly about the lack of rain and how it was affecting the grass. The next day my father helped him find work and a place to live, but he never once let him mow his yard. Sure, he asked the man for a hand the time he needed help digging out a tree stump after a big hurricane and later retrieving a dead possum and its babies from under the house. But otherwise, his yard was his yard.

After he turned ninety, my father fell and broke his hip while working in the yard and had to be moved into a nursing home. I would call him every couple days. Sometimes we talked about his physical therapy, sometimes about whatever hope of going home the doctor was giving him, sometimes about what kind of soup they had served that day in the dining room. I told him my wife and I were expecting our first baby and that we had just bought a larger house in Austin, but I knew a man stuck in a nursing home was only so interested in hearing about monthly visits to the obstetrician and rising interest rates. By the time my son was born, my father had been living in the home for three years, and there seemed to be fewer and fewer things for us to talk about. His life was growing fainter and mine was unfolding before me.

So we talked about yards: his old one, my new one. We talked about the rain or lack of it, the best time of day to water, when to use fertilizer, and the new lawn mower I’d just bought. I had researched the various models on Consumer Reports and finally settled on a Cub Cadet push mower, school bus yellow, with a built-in mulcher and an attachable bag for the yard clippings. He liked the idea of the attachable bag, but he wasn’t sure what I would need the mulcher for if I was taking care of the grass the way I was supposed to.

“And where do you think you’re going to store it, this new machine?” he wanted to know.

“In the garage,” I said.

“And if someone takes it?”

“Who’s going to take it from the garage?”

“Who’s going to take it?” he said. “People walking by, that’s who.”

I began to explain to him that our new house was in one of the safer neighborhoods in Austin, not anything like our old neighborhood, in Brownsville, where iron bars on the doors and windows were standard fixtures. Then I realized he thought my garage was a carport, open on all sides, and not a two-car garage (with an electric door opener even). No one in our old neighborhood had an actual garage.

“We have a little room where I keep the tools,” I said. “I can keep it inside there, locked up.” I failed to mention that the little room was really just a large closet inside the garage.

He had kept his machine locked inside the utility room behind the house. His was a fire-engine-red push mower with a side discharge that he’d bought at Sears. He checked the oil level each time he mowed the lawn. Afterward he would tip the mower on its side to scrape loose any clumps of grass that might be stuck to the blades or the housing or the side discharge, then do the same with any dirt or clippings that might have gathered on the deck or in the tiny grooves on the wheels. Once a year, usually in the early spring just before the grass started growing again, my father would take the machine to a neighbor who fixed mowers to look it over, make sure it was ready for the new season.

“And the yard?” he asked me one day on the phone. As usual, I was calling him on my half-hour commute back to the house.

“I didn’t have time this week.”

“Didn’t have time?” he asked, as if I’d told him I hadn’t managed to bathe.

“I have some deadlines coming up in the next couple of weeks.”

“And you can’t find an hour, even if you don’t trim around the sidewalk or trees? That rain last week must have made it grow, no?”

“Some,” I said.

The truth was, the whole yard was beginning to look pretty shabby. Though it was a modest size by most standards, the yard was still at least twice the size of the one I’d grown up with, not to mention the dozens of trees and shrubs scattered around the front and back. We had bought one of those houses with a yard everyone walking by would stop to gaze at, but not necessarily because of anything I had done. The previous owners were the ones who had built the redwood deck and added the marble steps that wove through the ground cover. They had trimmed the sprawling vines that hung just so and installed the ground lighting. The problem was finding the time to maintain it all.

I had a sense it wouldn’t do any good to remind my father that it had been only a few months since the baby had arrived (a boy!), which meant that when I wasn’t trying to finish my next book or teaching my classes at the university, I was learning how to feed, burp, bathe, diaper, swaddle, soothe, etc., etc., and doing most of this without much sleep. When I got around to working in the yard, it was usually a week too late, and by then the place looked abandoned.

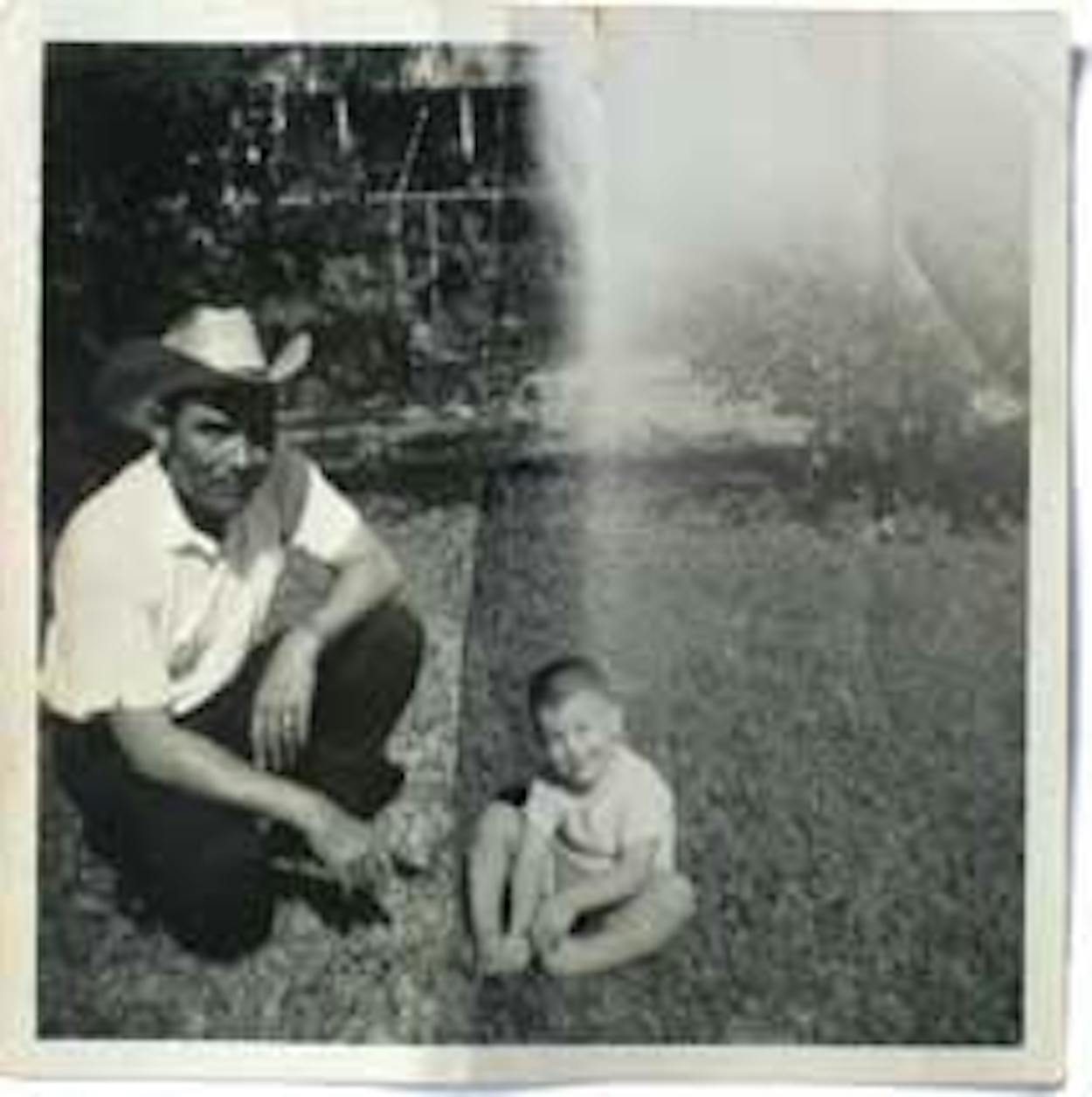

My father had a chance to meet my son (his tenth grandchild), but he saw my house and yard only in pictures. He died in his sleep five months after we moved in. When we got back from the funeral, I noticed that the garden was covered with weeds, and the ground cover had snaked its way across the marble steps. In the weeks that followed, I walked around wearier than I had when we were up all night with the baby. What little free time I had I spent in the yard. It seemed to be taking me longer to do the same jobs, but working was better than sitting inside feeling what I didn’t want to be feeling.

I wrote whenever I could. One Sunday morning I came out of my office and the house was empty. When I went to the window, I saw my wife holding the baby in the front yard. She was talking to a man standing beside a beat-up old truck with a mower in the back. The baby was pulling at the vines that were creeping up the metal bars of the fence.

“I have time to do it now,” I said when they came back inside. “I will next month, anyway, after I send off the draft.” She didn’t argue, though we both knew this was wishful thinking on my part. I was finding it hard just to help her with the baby, prepare for my classes, and finish the novel, which had already taken me five years. I would rush home from work in the evenings so I could spend the last fifteen or twenty minutes of daylight trying to scoop up the dead leaves that covered the front and back lawn, the long winding sidewalk, and both sides of the driveway. They clogged the rain gutter and wedged in the crevices of the gabled roof. Most times I was lucky if I had a chance to use the blower on the soggy clumps of leaves gathered along the curb. When I finished, almost always in the dark, my dinner was waiting for me in the microwave; the baby had by then had his bath, bottle, and gone back to sleep.

This went on for several months, me refusing to consider someone else taking care of the yard and the yard more often than not looking as if the tenants had left town in the middle of the night. Finally, I picked up the phone and called the yardman who’d come by that day. I told my wife it was because of the final revision of the novel. I had sent off the early draft knowing that it still needed work, and now I had to shorten some sections and expand others, a process that was bound to take me another couple months. But I had been avoiding this phone call for other reasons too. Yard work was all I had left of my father. How could I turn my back on that part of myself?

The yardman came by late in the afternoon. He had meant to show up earlier but had gotten lost and couldn’t find anyone he could ask for directions. My wife had gone to the store to buy more diapers, so I stepped outside with the baby to explain what we needed done. The man listened well, waiting for me to finish telling him about the monkey grass and the cast-iron plants and the weeds along the back fence, all of it probably already apparent to someone who did this kind of work for a living. Though he’d brought his mower, I told him I preferred that he use my machine and then showed him where it was in the garage. I finally left him when my son let me know it was time for his next feeding. Then we went back inside and sat by the front window, where together we could watch the man do his work.