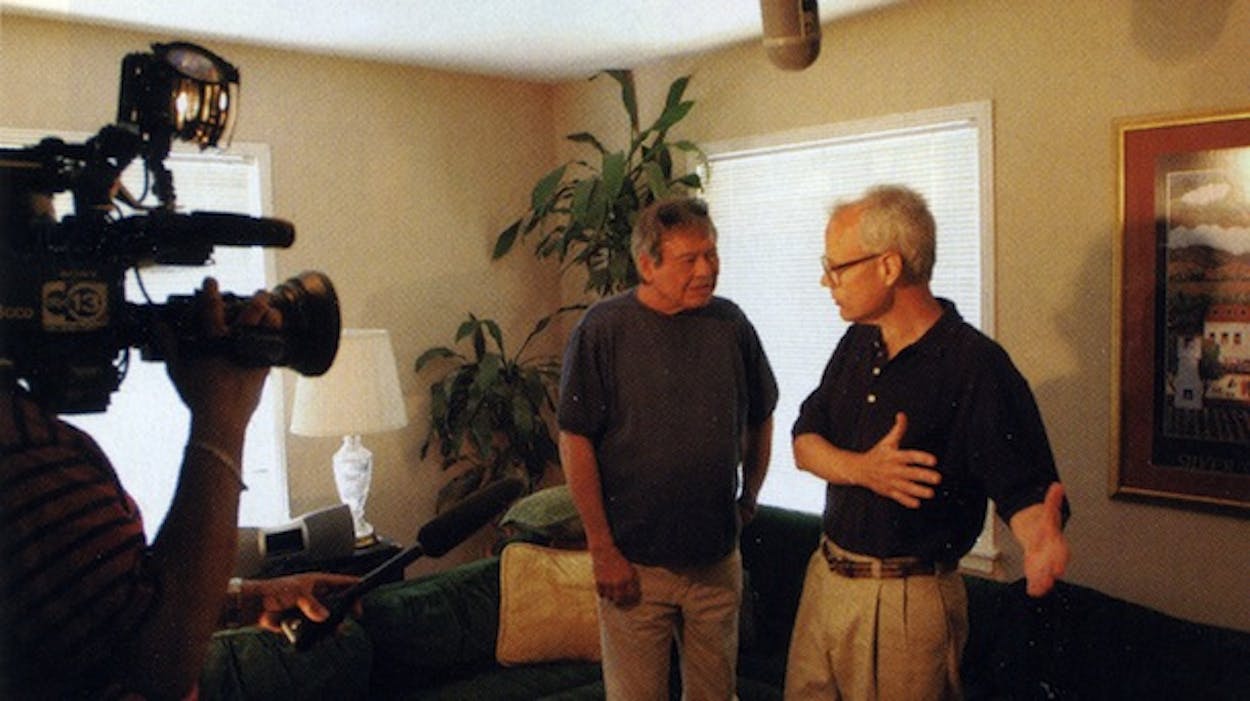

Greg Ott had been on my mind since January, when I testified at his parole hearing, but until I saw him on May 25, just after he was released from prison, I had seriously doubted this day would ever come. He had been locked up for more than 26 years. Now he was at the Houston duplex of his attorney, Bill Habern, who has represented him pro bono since 1990. I had been following Ott’s case for Texas Monthly since he was sentenced to life in prison for the murder of Texas Ranger Bobby Paul Doherty during a botched drug raid at Ott’s house, near Denton (“The Death of a Ranger,” August 1978). I’d trailed him through half a dozen failed parole hearings and had written about him again four years ago (“Free Greg Ott!,” August 2000).

A model inmate, Ott was caught in a web of politics and recrimination, his case one of the most emotionally explosive the Texas Department of Criminal Justice and the Board of Pardons and Paroles have faced. It made no difference to the Rangers that the fatal shot was unintentional and not an act of cold-blooded murder. Retired Ranger captain Bob Prince, in particular, had made it his mission to keep him locked up. Ott had been approved for parole in 1990 and again in 1999, but each time, the parole board reversed itself at the last minute, buckling under an avalanche of protests orchestrated by Prince.

Now 53, Ott was frailer and grayer than when I’d last seen him, but that glaze of submission in his eyes was softer and livelier. He had already lined up a job as a maintenance man at a shopping center in the Orlando area, near where his sister and elderly parents live. At the time of his arrest, Ott was a brilliant graduate student in philosophy at North Texas State (now the University of North Texas). It pained me to think of him mowing grass and cleaning restrooms, but the prospect seemed to make him happy. “All work is honorable,” he told me in his quiet voice. Ott had done his time without a trace of bitterness or hatred, following orders, accepting guilt. “I strive to be part of solutions, not problems,” he explained.

Ott might still be in prison if two television shows last year—one an installment of A&E’s American Justice series and the other a Court TV special meticulously researched by Catherine Crier—hadn’t championed his cause. Crier, who graduated from the Southern Methodist University law school and has worked as a prosecutor and a judge in Dallas, used her daily show to crusade for Ott’s parole. Her efforts elicited a flood of letters and e-mails to Governor Rick Perry’s office and the parole board, prodding a review of Ott’s status. At the hearing in January, Crier told parole board member Lynn Ruzicka, “If this [crime] had happened today, in 2004, it would probably be prosecuted as manslaughter” (for which the maximum sentence is twenty years). A few months later, Ruzicka, who teaches criminal justice at the University of Houston-Downtown, approved Ott’s parole and held her ground against protesters. So did parole board member Linda Garcia, a former Harris County prosecutor, who had voted to free Ott in 1999 and cast the second and decisive vote this year.

But Greg Ott wasn’t the only one who had been on my mind. I’d also been thinking of Carolyn Doherty, the slain Ranger’s widow. When I spoke with her a few years ago, I asked how she would feel when Ott was finally set free. A gentle and forgiving woman, she told me that she would be relieved. She would no longer have to join the Rangers’ protest every several years; she could close that chapter of her life, knowing she had done all she could for her husband.

As for Ott, he bears no malice toward Bob Prince or any of the hard-liners who opposed his parole. “I understand esprit de corps, loyalty,” he told me. “They are noble traits. I only wish they would understand I never intended to kill anyone.”