When I told my mom, back in 1970, that I was going to write a dissertation on Frank Norris, she was excited; she thought I had in mind the feisty Fort Worth preacher J. Frank Norris, a celebrity in my parents’ day as big as Bonnie and Clyde. Her excitement faded when my Frank Norris turned out to be the late-nineteenth-century American novelist, author of McTeague and The Octopus.

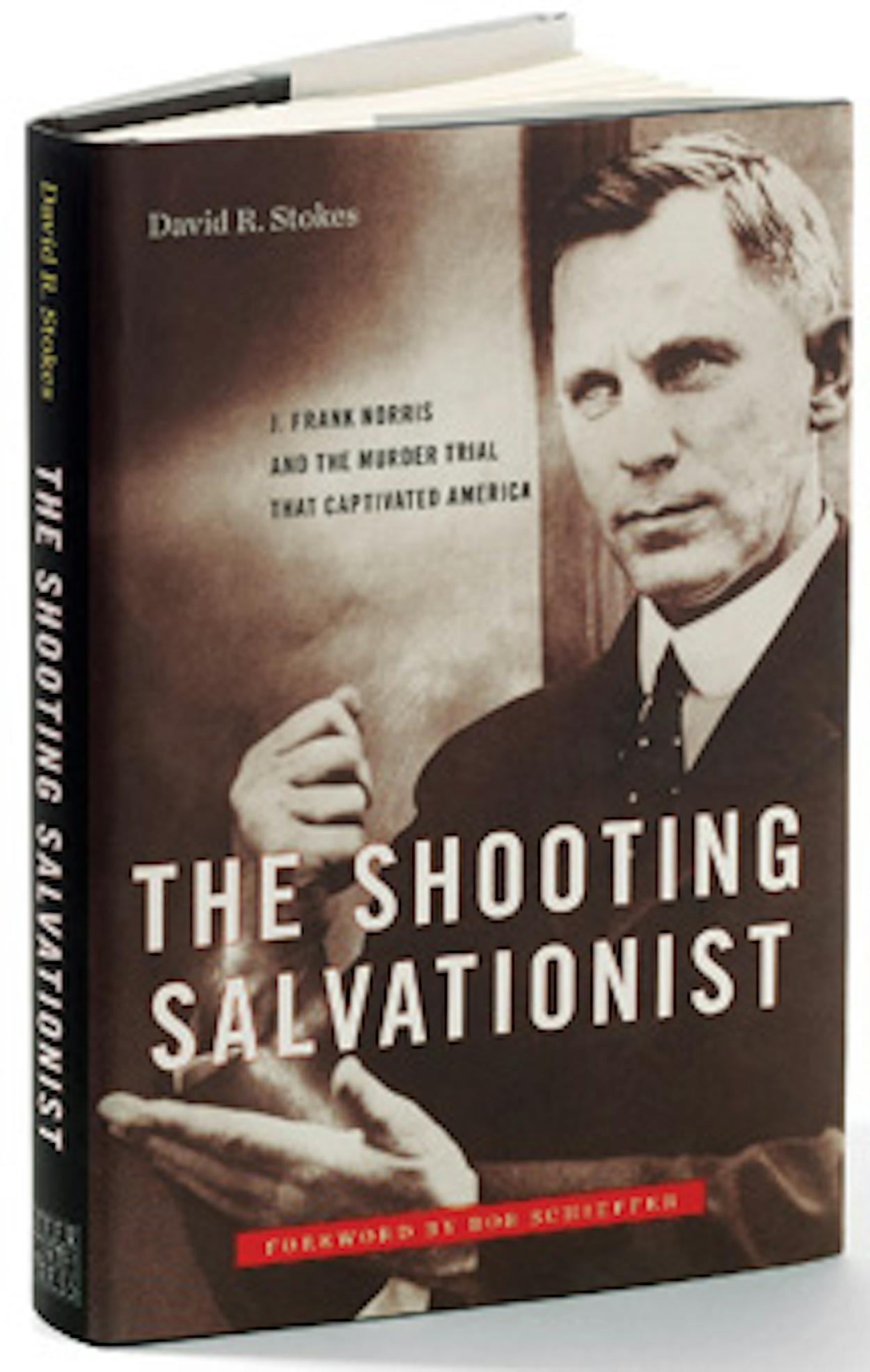

Mom’s Frank Norris, by contrast, was America’s most famous fundamentalist preacher between Billy Sunday and Billy Graham. The task undertaken by author David R. Stokes in The Shooting Salvationist: J. Frank Norris and the Murder Trial That Captivated America (Steerforth Press, $27) is to breathe life and relevancy into Norris’ story. Other authors have tried without much success to do the same. Barry Hankins’s God’s Rascal (1966) portrays Norris as a cultural figure but offers minimal information on the man and his motivations. Other books, most published by church-related presses, focus on Norris the groundbreaking Southern fundamentalist. Stokes, who is senior pastor of Fair Oaks Church in Fairfax, Virginia—“Who better to write about the flaws of a pastor than a pastor?” he has said—declares that his book is “not a faith book” but a story that “reads like a novel.”

It does not, though the materials for a novel are certainly here. Born in Alabama in 1877, John Franklyn Norris moved with his family when he was a young boy to Hubbard, a small community southeast of Hillsboro. Norris’s father was a sharecropper and a bad drunk, from whose example Norris acquired a lifelong detestation of alcohol. Norris discovered his religious calling early, at a revival meeting in 1890. He entered Baylor University in 1898 and a year later had his first pastorate, in nearby Mount Calm, at the ripe age of 21. In 1905 he took a master of theology degree from Southern Baptist Seminary, in Louisville, Kentucky. The top in his class, he gave a valedictory address on “International Justification of Japan in Its War With Russia.” That must have been a spellbinder.

After a four-year stint at the McKinney Avenue Baptist Church in Dallas, Norris jumped to Fort Worth’s First Baptist Church. Here he would accomplish his rapid climb to acclaim and influence as well as put his life at risk with his combative zeal. Within just two years Norris had turned himself into a sensation—and made a lot of bigwigs in Fort Worth very angry when he denounced Hell’s Half Acre, a swath of bars, whorehouses, and gambling establishments that were sources of sin and income for city leaders. The consequences were swift and dire. In 1912 Norris’s church was burned to the ground, his house was damaged by fire, and two bullets shattered the stained-glass windows of his study. Though as was often the case with Norris, it’s not clear who had done what. (There were rumors that Norris himself was the author of some of these actions.)

None of these events deterred him. By the mid-twenties Norris oversaw a virtual communications empire. Besides producing a steady stream of articles for his tabloid, The S light, he broadcast sermons and political rants on his radio station, KFQB, which billed itself “Keep Folks Quoting the Bible.” Everything came to a head in the summer of 1926, after Mayor H. C. Meacham sought to heavily tax Norris’s empire. Norris responded by accusing the mayor of graft and dropping hints about a sexual relationship between Meacham and a young woman. The mayor retaliated by firing several employees of his department store for refusing to give up their membership in the First Baptist Church. This kind of heavy-handed tactic only gave Norris another reason to bash the mayor, which he did on an almost daily basis. Many people in Fort Worth wanted Norris dead, and one of them, a friend of the mayor’s named D. Elliott Chipps, decided to deal with Norris personally. Known to be belligerent when drinking, Chipps confronted Norris in his church office on a hot July afternoon in 1926. The visit ended when Norris fired three bullets into Chipps’s body, an act that captured the nation’s attention.

This event happens on page 108 of The Shooting Salvationist, and for the next 214 pages we are presented with every scrap and fact available, including a detailed play-by-play of the contentious trial held in Austin in January 1927. For data and context, Stokes has gone back to the microfilm copies of newspapers of the period. This is hard, grinding research (done in part by paid researchers), but the payoff is not particularly insightful. The whole book (which was self-published last year in significantly different form under the title Apparent Danger) has a kind of faded Front Page quality. Cliff-hanger chapter endings and hokey chapter titles—“Extra, Extra, Read All About It!” “Hello Chief, Let’s Go,” “If You Do, I’ll Kill You”—do little to increase interest. Too often Stokes seems to be the captive of background research. You can almost hear index cards being turned over as he reports the rise of the council-manager form of city government in the twenties and the political campaigns of forgotten figures like Lynch Davidson and Dan Moody. And as with the other books on Norris, the man himself remains elusive.

Stokes wants us to see Norris as a “sobering reminder that any cult of personality . . . is fraught with peril.” But Norris, I think, was something else: a figure who bridged fire-and-brimstone sermonizing with the modern communication techniques of print and radio. In many ways he was the prototype of the modern megachurch minister. What he was not was a crazy cultist like David Koresh, who holed up in his own little Alamo, or that nut job in West Texas who dressed all his women like calico extras in a wagon train western and married more than his share of them.

It’s easy today to dismiss faith fanned by the flames of old-time religion. Sinclair Lewis did it in Elmer Gantry (published in 1927, the year of the Norris trial), whose protagonist was an unscrupulous, showboating preacher. But in that distant time, the power of fundamentalist theology was palpable. Revivals in Texas were sources of great energy and consolation. Although I was bored with the plain-vanilla sermons of the resident pastor of the Protestant church my family attended in Lucas, in Collin County, I was much impressed with the summer revivals held in an open wooden tabernacle in Forest Grove, a few miles north. Those preachers were rhetorical geniuses with staying power; they never closed out the night’s session until a sufficient number of sinners had come forward to be saved. Once, at another revival, I heard a former member of the Bonnie and Clyde gang talk of sin and redemption.

That was a long time ago, but I still remember the excitement of those blazing-hot summer nights of fervor and entertainment. I wish Stokes had been able to get across some of this. Perhaps it really will take a novelist’s skill to bring J. Frank Norris to life on the page.

Textra credit: What else we’re reading this month

Close Your Eyes, Amanda Eyre Ward (Random House, $25). Literary whodunit based on a real-life murder, from the Austin author of the acclaimed How to Be Lost.

The First Days, Rhiannon Frater (Tor, $14.99). Hill Country–set first novel in a female-centric zombie trilogy that began life as a self-published book.

What Harvest, Floyd Collins (Somondoco Press, $15). A series of deeply imagined, finely detailed poems on the siege and battle of the Alamo.