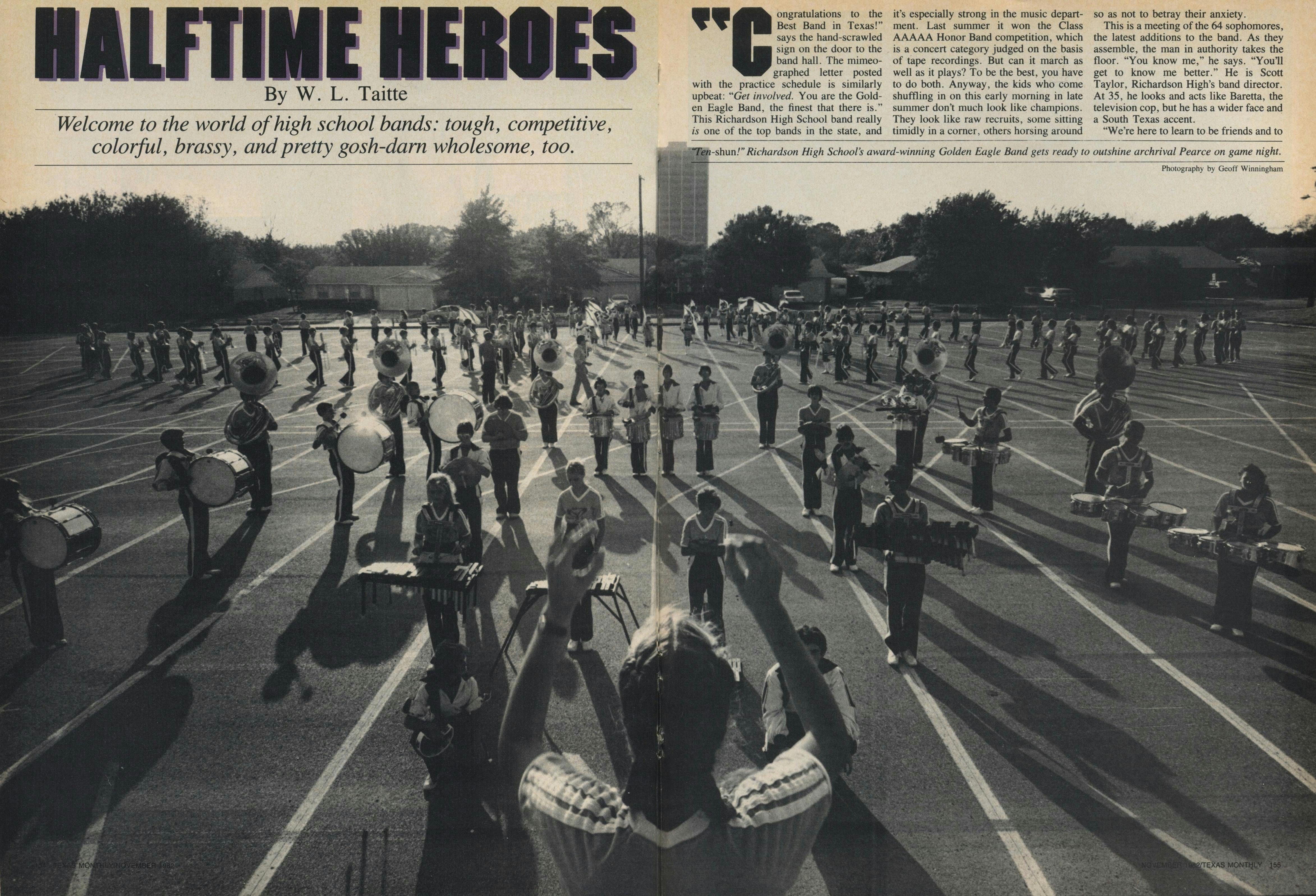

“Congratulations to the Best Band in Texas!” says the hand-scrawled sign on the door to the band hall. The mimeographed letter posted with the practice schedule is similarly upbeat: “Get involved. You are the Golden Eagle Band, the finest that there is.” This Richardson High School band really is one of the top bands in the state, and it’s especially strong in the music department. Last summer it won the Class AAAAA Honor Band competition, which is a concert category judged on the basis of tape recordings. But can it march as well as it plays? To be the best, you have to do both. Anyway, the kids who come shuffling in on this early morning in late summer don’t much look like champions. They look like raw recruits, some sitting timidly in the corner, others horsing around so as not to betray their anxiety.

This is a meeting of the 64 sophomores, the latest additions to the band. As they assemble, the man in authority takes the floor. “You know me,” he says “You’ll get to know me better.” He is Scott Taylor, Richardson High’s band director. At 35, he looks and acts like Baretta, the television cop, but he has a wider face and a South Texas accent.

“We’re here to learn to be friends and to excel,” he goes on. “We’re not here to humiliate you. There are times when you will feel bad, embarrassed. It’s not intentional and we’ve all been through it. It’s short-lived. On September third you are going to have to set foot out there on that football field and perform. You have to be aggressive if you want to succeed.”

The Richardson High School band has had notable success in playing and marching, but that does not make it particularly unusual. Texas bands are the finest in the country—the three dozen or so best high school bands in the state could be matched by perhaps only a dozen others throughout America. Every fall, thanks to God, 3,500 band directors, and 350,000 indefatigable band members, the show resumes all over Texas. From Monahans to Houston, Amarillo to Brownsville, and points between and beyond, that show is apt to be the best band in town on any given weekend night. Whether you have kids in high school or just an active nostalgia of your own adolescence, you can’t help but be attracted whenever you get within earshot of a high school stadium on a fall evening. The swarm of spectators, the blaze of the stadium lights, and especially the music drifting through the air make you feel a little left out. And that is the power of Texas’ high school marching bands: you want to drop what you’re doing and join the crowd.

How did Texas come on such preeminence? How did it happen that the Richardson High School band is generally more successful than its football team and appears to have a lot more fun? How, for that matter, did it come to pass that the children of cowboys, farmers, and rough necks put on uniforms and picked up the piccolo and the snare drum and the tuba?

Bands came to Texas because it was frontier, not in spite of that fact. Brass bands gained prominence in the Civil War, and their importance increased after the war with the success of sit-down-band composers like John Philip Sousa. As the west was being won, the little towns that wanted some music in their opera houses could seldom find anybody to play a sissy instrument like the cello, but there was always someone who could play a horn—the generic name in band parlance for any wind instrument. Eventually bands worked their way into the schools. An important reason, of course, was football. Texas A&M was one of the first schools in the country to have its band put on a halftime show, sometime back in the twenties. Others soon followed, and in the 1935-36 school year, Abilene High School became the first high school in Texas to make music part of its curriculum. Other states that were high on football, like Michigan, were band-crazy too. But over the last forty years a number of factors have helped Texas win out over its band-and-football rivals.

First is climate. Who wants to march in Michigan after October? Second is the irrepressible enthusiasm of Texas’ local citizenry, who will raise large sums to supplement their band programs. The University Interscholastic League, which formulates regulations for all sorts of Texas school competitions, including musical ones, has also whetted the competitive instinct in Texas. And in recent years there has been money available in Texas and not elsewhere. This year as many as three hundred band directors from other states have found employment here.

Most important, though, is the political acumen of the music teachers and their supporters. The Texas Music Educators Association is smart and well organized; its executive secretary, Bill Cormack, may be the only ex-choir director in the country who is a registered lobbyist. The TMEA has managed to get the Legislature to declare fine arts, including music, a basic subject on par with the three R’s. That is why the kids learning to march in Richardson mastered music in junior high that students in other states won’t tackle until college. The Golden Eagle won their Honor Band contest by playing knotty pieces by modern composers Percy Grainger and Aaron Copland.

Marching bands have undergone three revolutions in the last forty years. All bands started out using military-based marches with shoulder-to-shoulder, precision drills and a long marching stride of six steps to five yards. East Texas bands still favor a military marching style, but the rest of the state changed from close-order drills to shows with a theme—pumpkins for Halloween and turkeys for Thanksgiving—and a shorter stride of eight steps to five yards. Most Texas bands changed a second time when theme shows were replaced by abstract and geometric designs constructed by field-filing assemblages of musicians, flag bearers, drill teams, and majorettes.

The third revolution in marching style came in the seventies when the rest of the country was swept by a fad for drum and bugle corps: independent marching organizations, not sponsored by any school, that cross the country year-round to compete in elaborate contests. Texas has only a few such corps—school traditions have been too strong here, and music-minded Texans do not want to keep on marching after football season.

The zippy show-biz style of the corps and its free-flowing curvilinear patterns have nonetheless left their mark on Texas bands. Towering shakos, the hats that made drum majors look like Buckingham Palace guards, are on the way out. Aussie hats are in. The marching patterns are now so complex that a band spends a whole season learning a single show. Even the sound has changed. The typical percussion section used to consist of eight snares and two big bass drums. Now it may include more than twenty players who perform on every conceivable percussion instrument, most of them requiring a great deal of skill to play. The percussion music is so complex and some of the instruments so unwieldy that the percussion section no longer marches with the rest of the band. Instead, it forms its own distinct unit on the field.

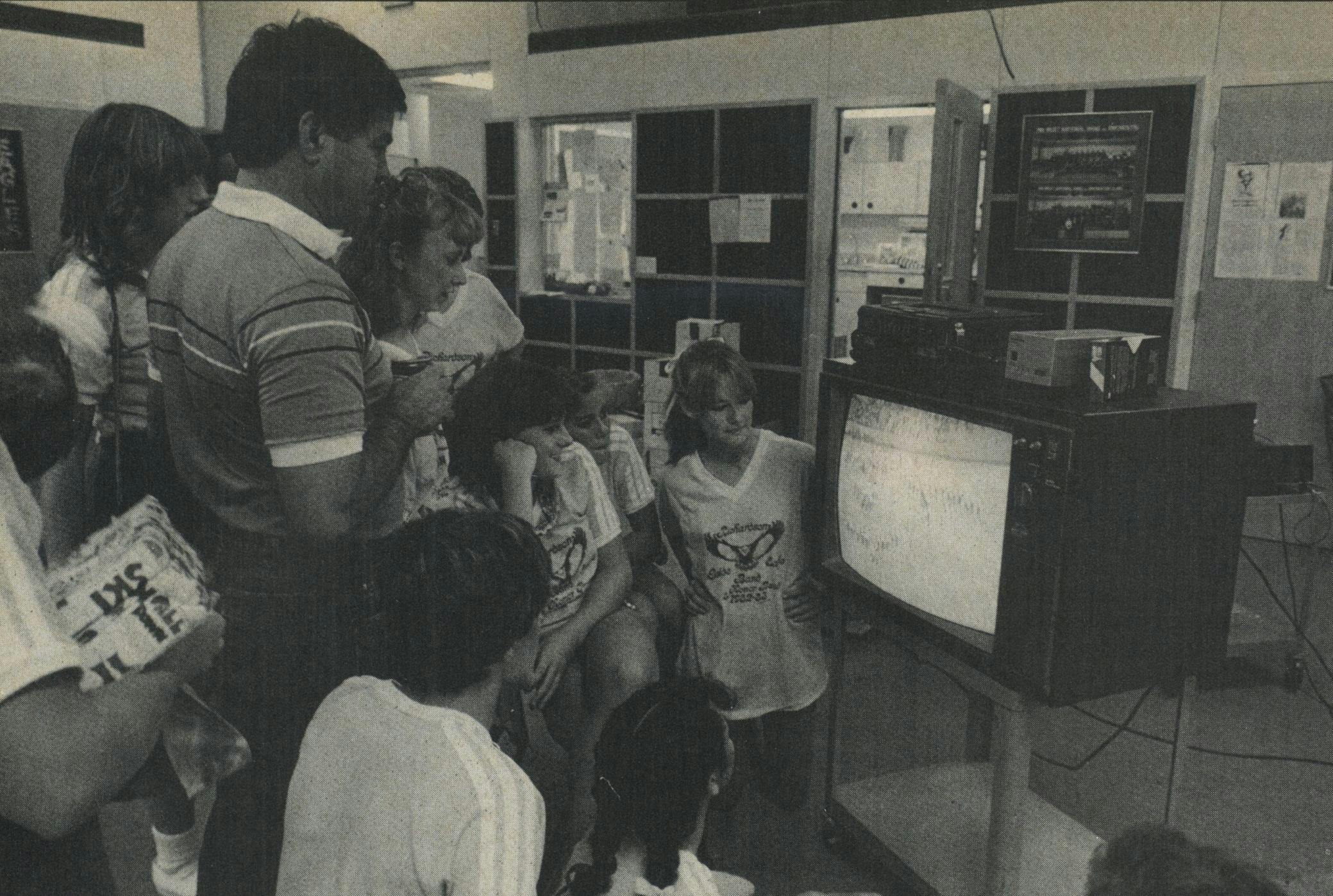

Music has become a big business in the large Texas high schools. For years Texas bands traveled to Chicago to play at the Midwest National Band and Orchestra Clinic. The Richardson band made such a trip last winter. Many of the same kids went with the Richardson school orchestra to play at an international youth music conference in Vienna last summer. To master the advanced musical literature that a program like Richardson’s takes for granted, 80 per cent of the students take weekly private lessons ($6.50 for half an hour) from school-approved teachers during school hours. There is also such strong competition for original music for halftime shows that many bands hire composers to write new material—or as Richardson did this year—pay arrangers to score pieces specifically for band instruments. Every year the big bands make record albums to document their performances for posterity.

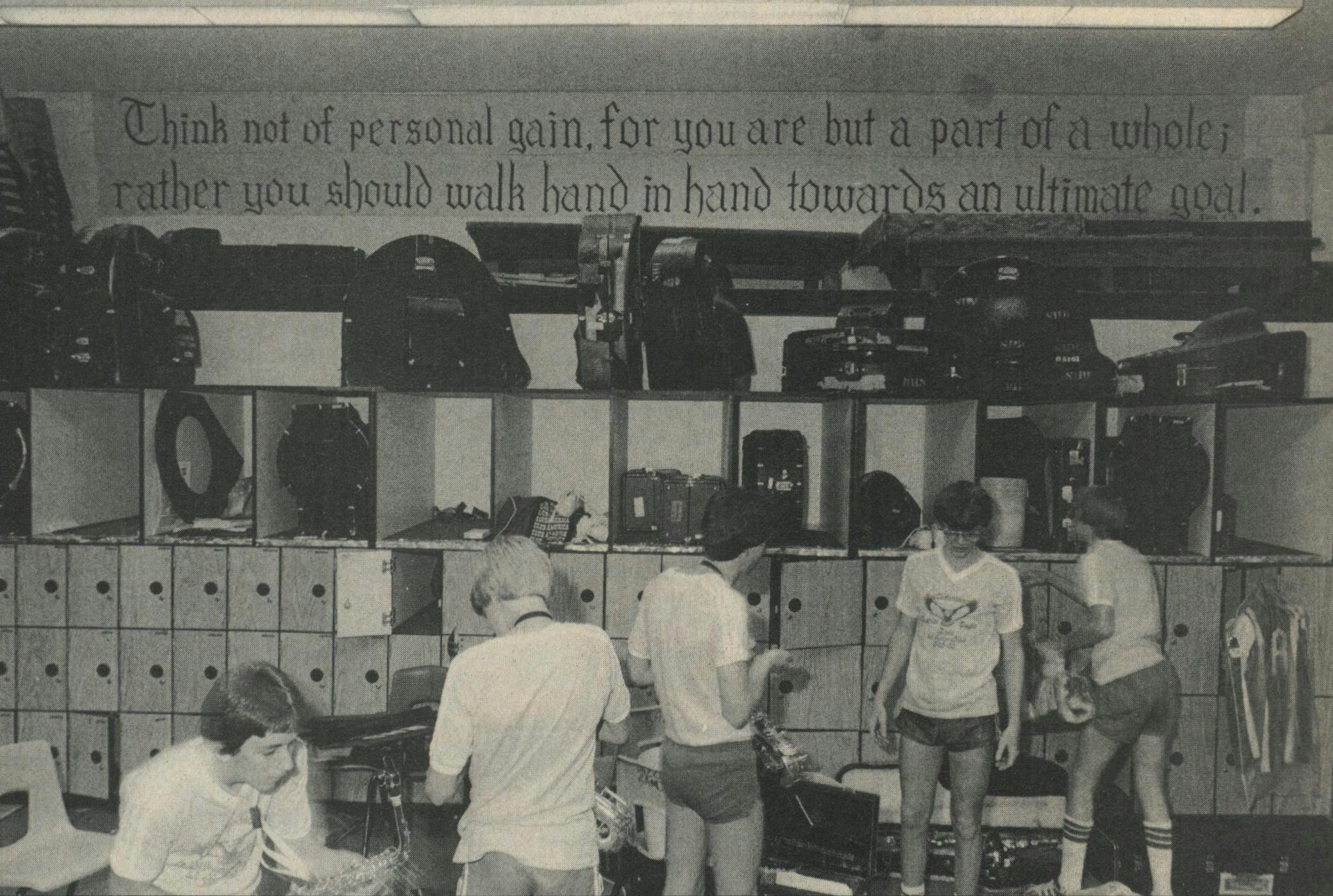

But some things never change—like white shoes. When I was in high school, white bucks were almost a stigma. Band kids were, to use a term we didn’t have then, “dorky.” Now partly because of their success, the kids seem less square. But they are still aware of certain prejudices against them, and the sense of being left out draws them closer to their compatriots. If you wonder why a kid would take the risk of being in the band, all you have to do to answer your question is visit the band hall during a rehearsal. The band hall is the totemic meeting hall of the clan that makes music. Amid all the free-for-all atmosphere—more than a hundred kids playing, the drum majors watching a videotape of a marching contest, new kids trying on uniforms—there is disciplined concentration.

It is the day before Richardson’s first game, against the big high school in Duncanville, a growing community on the south side of Dallas. After three weeks of practice, the band finally gets to play and march at the same time; both playing and marching collapse. The sophomores start to panic, and old hands like the first trumpets break discipline to shout reminders to them. It doesn’t help. Scott Taylor remarks, “Anytime you add something new to the mix, the band retards.” He tells the right half of the formation to fall out and play the music on the sidelines while the left half just marches and counts and hums.

The evening sky is threatening the first real rainstorm in nearly two months, and the assistant band directors are trying to calm the kids down, though they aren’t feeling very secure themselves. To the east and south, dark billowy clouds are piling up, shot through with flashes of lightning, but the sky over the parking lot is clear. The hole in the clouds seems a miraculous intervention to keep the rehearsal rolling. Taylor bucks up the kids when they try again. “That’s not great, but it’s better—the difference must be coming from what’s going on under those hats.”

As the sun gets lower, a triple rainbow forms in the eastern sky. Taylor tells the kids that God’s apparent optimism for this whole project is going to be justified. “Were always having to tell you what’s wrong with what you’re doing rather than what’s right,” he says. “I hope that not for one minute do you think that we’re not proud of what you’re doing. Tomorrow’s the day. Make it a good one.”

The kids whoop and clap and beat the drums, and after some announcements, the head drum major, Martha Wilcoxson, shouts, “Di-is…missed!” and is answered, “Gol-den Ea-gle Band!” They don’t break until she cries, “Fa-all out!”

They are back on the lot at seven sharp the next morning. It is going to be a big day. This morning’s rehearsal will be the first time the band marches on the football field—Taylor and the assistant directors have been grumbling among themselves about waiting so long—and it will be hard going because for the first time the kids won’t have the help of the red and white lines that crisscross the parking lot where they’ve been practicing. After this practice, there will be another sit-down rehearsal in the band hall, the first pep rally, a final rehearsal, and the game itself.

The band directors climb up to the roof of the press box on the west side of the field to watch. The morning is the first crisp one of the season—you could almost convince yourself that it is fall and really time for bands and football games. There is nothing much to do at this point but let the band go through the routine a few times and try to correct the placement as much as possible. Two of the three drum majors act as sheep dogs to try to keep the arcs in line while Martha Wilcoxson directs.

After a frenzied pep rally at the school, the band has the last rehearsal at 5:15 p.m. out on the parking lot. Again it is back to fundamentals. Taylor shouts advice. “Look at the bodies next to you, don’t look at the ground.” To Wilcoxson: “Don’t let those hands sag, Martha. Keep ’em up.” And again: “Tubas, watch that waddling onto the field. It looks like Penguin City.”

They go through the show three or four times and finally look more secure. “That’s about a thousand times better than it’s been, folks,” Taylor says as he gives the band permission to go into the band hall to get ready for its first performance.

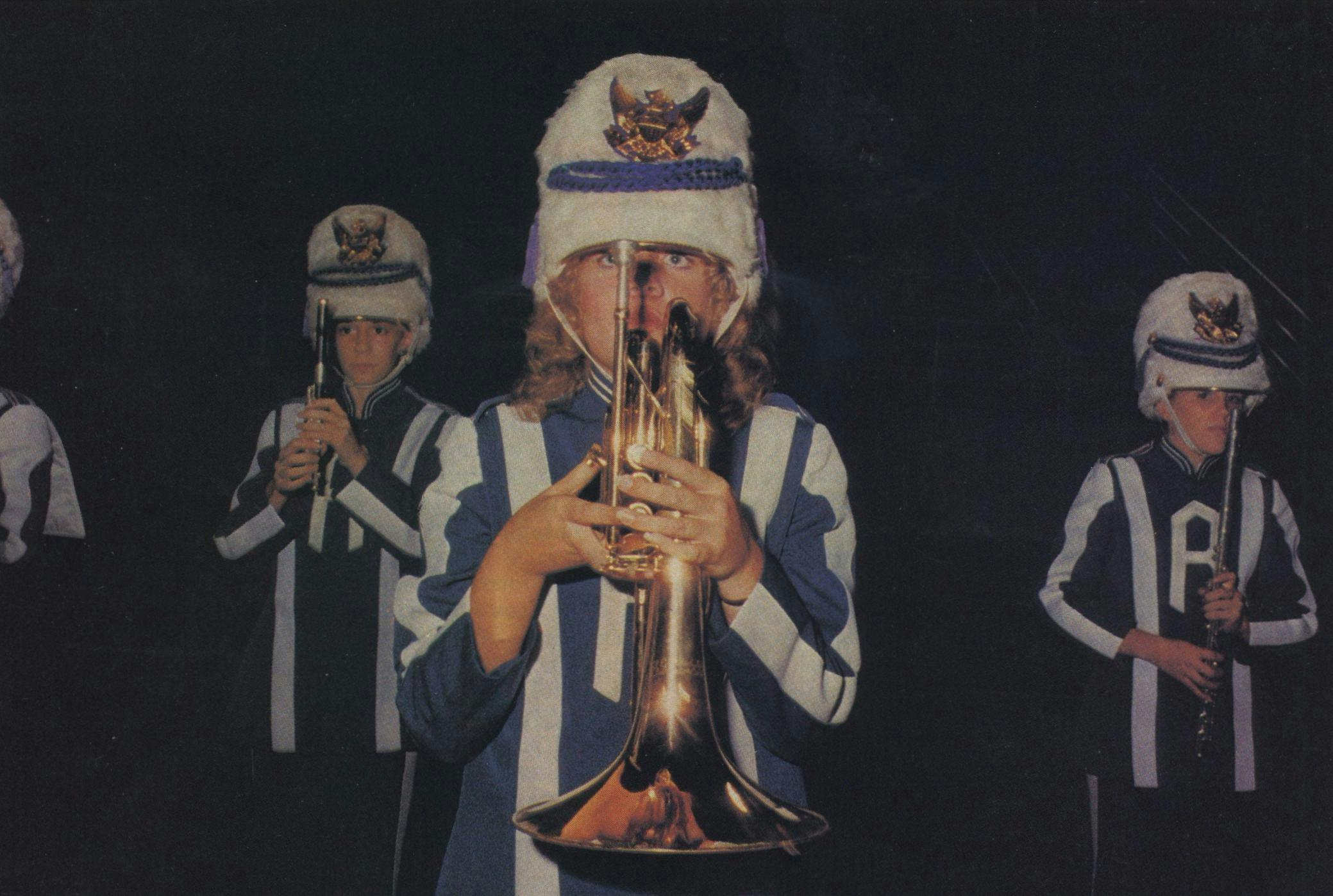

When every uniform has been snapped and zipped in place and every white shoe polished, the drum majors head up the marching line to take the band from the lot outside the band hall to the stadium. Martha has on a purple wool prairie skirt and blouse, and all three drum majors wear great gold satin capes that look like cardinal’s copes.

They are followed four abreast by the flag bearers (who look like Annie Oakley cloned sixteen times), then the tubas, the rest of the brass, the percussion, and the woodwinds—piccolos last. At the rear are the extras who have just joined up. A new drummer is wearing two right white shoes somebody dug up for him, and because he has not yet been assigned an instrument, he carries, poker-faced, Taylor’s bull-horn. The percussion plays the marching beat, a hot-sauce bossa nova that attracts a crowd. Though it is more than half an hour before game time, the band marches proudly into the stadium.

The band sits high in the bleachers at the forty-yard line, its straight vertical rows behind the mass of gold and purple pom-poms of the drill team. Band alums from A&M and Tech come by to visit, and ninth-graders who can’t wait to be in the band pester the kids in the front rows. The crowd pays more attention to the Richardson school song than to the national anthem, and after opening ceremonies the band members are allowed to take off their jackets, revealing matching gold T-shirts underneath.

With 9:52 to go in the second quarter, the flag bearers take their banners down to the field; they are disappointed that the new silks ordered for this season were not finished in time for the game. The percussion players slip on their bulky harnesses. At last the shakos that most of the marchers wear go on, and the band moves down to the field in marching order.

After the visiting Duncanville High School band has finished its act—a showy one of an older fashion, with more than 350 kids in the field—the Richardson band gets its chance. “Ladies and gentlemen, the pride of Texas, the Golden Eagle Band. Find your favorite band member and watch his progress throughout the season as we take our show and refine it to a competitive edge.”

The marchers stride on to the field to take their places for the first set, a double diagonal line with two wide arcs sweeping away from it. The drum majors come downfield to do their own synchronized salute, and Martha climbs onto a portable podium decorated with a student painted eagle . Hoping to be heard, she shouts, “Mark time, mark. Ready and …” as she claps her white-gloved hands.

From the first heavy “oom-pah, oom-pah-pah-pah” with which the tubas establish the rhythm of “Malagueña,” nothing seems to go quite right. Without those red lines and the verbal orders from the drum majors—who tonight just beat time—the circles jerk out of shape and collisions seem imminent at every moment. The mellow tone the band is famous for has disappeared. The music sounds more like it is being played back over a cheap transistor radio, and when the trumpeters congratulate each other with an exuberant high five after the duet you wonder what they are celebrating. The flag routine is so out of sync that you don’t realize it is supposed to be together.

This evening the announcer’s suggestion to keep watching the Golden Eagles is well advised. Everybody knows there is work to do. Nobody knows better than Scott Taylor, who has seen it all before.

It is back to work on Monday, even though it is Labor Day. Not only does the band have another home game at the end of the week but it also has to perform at a TCU game in Fort Worth on Saturday night. Sloppy execution of a fancy show will not do.

By Friday the band is up for performance. The competition, from Carter High School of Dallas, is a small band but a surprisingly ebullient one. And finally the stadium loudspeakers are echoing once again, “Ladies and gentlemen, the pride of Texas…” If the Golden Eagles are going to regain their pride, this had better be good.

As Martha gives the signal, the lower instruments begin the somber, pounding rhythm of “Malagueña.” The brass players stop ceremoniously, as if they were in a royal procession, up to the heads of their lines and turn sharply, one to the left, the next to the right. The flags, in unison, semaphore a jerky, wide-ranging salute.

As the tempo quickens in these opening flamenco fanfares, the percussion group marches backward as a tightly spaced unit until it becomes the foundation of the line of six tubas. Around this core, the entire brass section forms a perfect circle. At the end of another radius farther out is an arc of woodwinds. The flags form two shallow arcs stretching from the center out to the woodwind periphery—and tonight they are proudly hoisting their just-finished silks of translucent metallic purple and satiny gold.

At the point of transition into the tingling “Silence and I,” the marching erupts into kaleidoscopic motion, with arcs swinging every which way, as the music takes off. When the spangled percussion patterns settle down into a definite rhythm, the arcs coalesce into a shape that resembles the face of a fly—big circular eyes joined by lines that meet to form a sharp nose. As the music rises to a climax, the whole shape propels itself towards the audience. The brass blasts the audience out of its seats, and the impression of speed and power is overwhelming, especially if you are on the sideline as the formation comes swooping at you.

Next is a little bow to the old-fashioned tradition of marching in straight lines and stepping off them one person at a time. These fifteen seconds are almost an in-joke saying, “We can do this, too.” But these straight, parallel lines marched to punchy, brassy music are the last you will see. The music is now going into the love song from Superman, and the designs evolve into soft, curvaceous, flowing shapes. The music, too, is the farthest thing from Sousa. Flutes and saxophones establish a shimmering background, and the two solo French horn players—senior Kathy Lysen and junior Carol Wilgus, who is a ranking member of last year’s all-state orchestra—are left alone at the front to play a romantic duet. The song is subtle, yet it is still outdoor music. At the end, the Spanish fanfares return, and the crowd goes wild for the home team. There have been a few missteps, but this week the basic performance has come together. From here on out, it will be detail work and polishing.

During the second half of the game, the band is in a different mood from last week. Allison Chambers, a sophomore trumpet player from England, is hyper with joy. “Honestly, I was so excited when they said ‘the pride of Texas’ I had to wipe away a tear. Really, I’m not joking. I did.”

But Scott Taylor, realist that he is, knows the work is not over yet. “Somebody asked me, and I told him that on a scale of one to ten this was about a five tonight.”

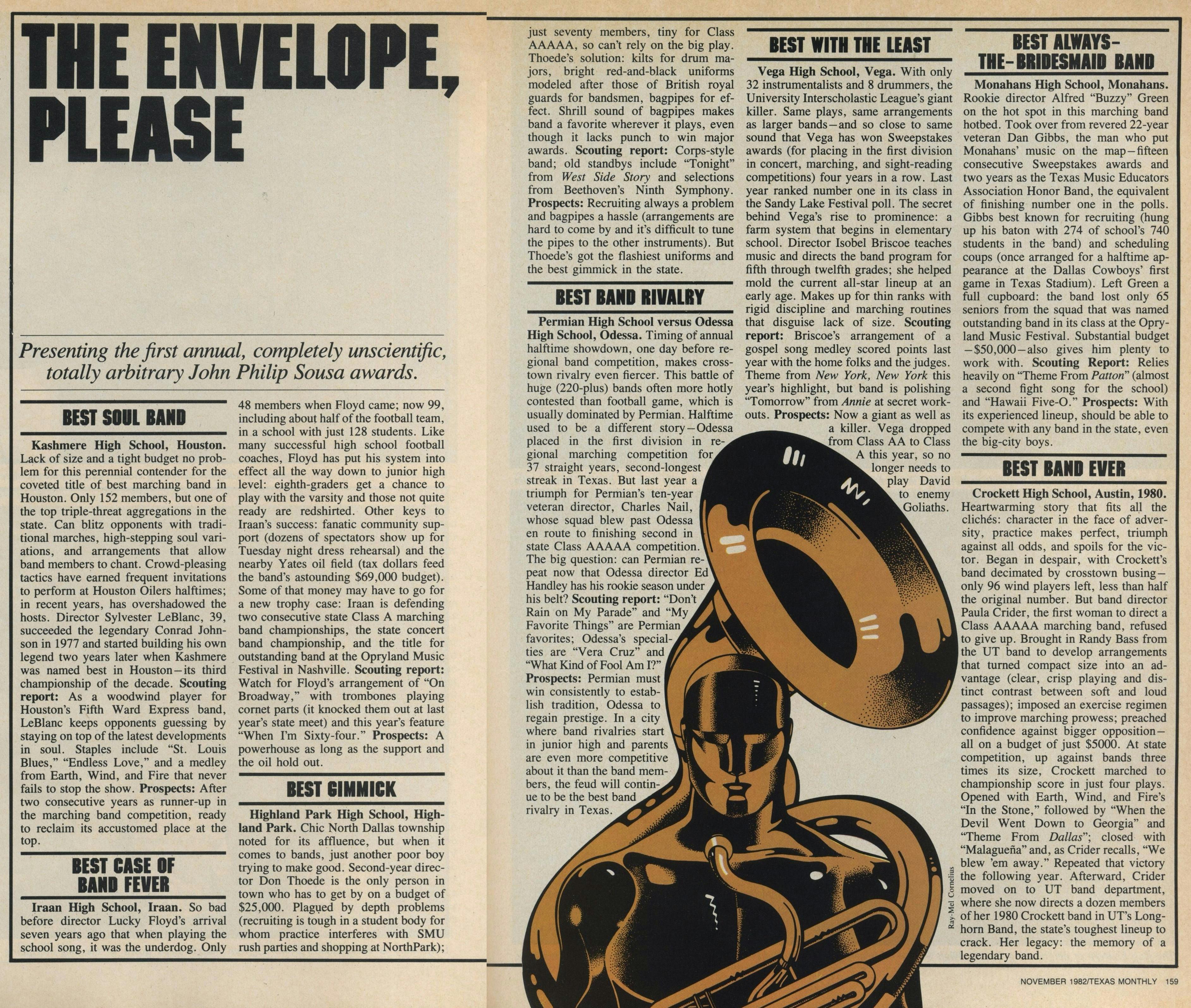

The Envelope Please

Presenting the first annual, completely unscientific, totally arbitrary John Philip Sousa awards.

BEST SOUL BAND

Kashmere High School, Houston. Lack of size and a tight budget no problem for this perennial contender for the coveted title of best marching band in Houston. Only 152 members, but one of the top triple-threat aggregations in the state. Can blitz opponents with traditional marches, high-stepping soul variations, and arrangements that allow band members to chant. Crowd-pleasing tactics have earned frequent invitations to perform at Houston Oilers halftimes; in recent years, has overshadowed the hosts. Director Sylvester LeBlanc, 39, succeeded the legendary Conrad Johnson in 1977 and started building his own legend two years later when Kashmere was named best in Houston—its third championship of the decade. Scouting report: As a woodwind player for Houston’s Fifth Ward Express band, LeBlanc keeps opponents guessing by staying on top of the latest developments in soul. Staples include “St. Louis Blues,” “Endless Love,” and a medley from Earth, Wind, and Fire that never fails to stop the show. Prospects: After two consecutive years as runner-up in the marching band competition, ready to reclaim its accustomed place at the top.

BEST CASE OF BAND FEVER

Iraan High School, Iraan. So bad before director Lucky Floyd’s arrival seven years ago that when playing the school song, it was the underdog. Only 48 members when Floyd came; now 99, including about half of the football team, in a school with just 128 students. Like many successful high school football coaches, Floyd had put his system into effect all the way down to junior high level: eighth-graders get a chance to play with the varsity and those not quite ready are redshirted. Other keys to Iraan’s success: fantastic community support (dozens of spectators show up for Tuesday night dress rehearsal) and the nearby Yates oil field (tax dollars feed the band’s astounding $69,000 budget). Some of that money may have to go for a new trophy case: Iraan is defending two consecutive state Class A marching band championships, the state concert band championship, and the title for outstanding band at the Opryland Music Festival in Nashville. Scouting report: Watch for Floyd’s arrangements of “On Broadway,” with trombones playing cornet parts (it knocked them out at last year’s state meet) and this year’s feature “When I’m Sixty-Four.” Prospects: A powerhouse as long as the support and the oil hold out.

BEST GIMMICK

Highland Park High School, Highland Park. Chic North Dallas township noted for its affluence, but when it comes to bands, just another poor boy trying to make good. Second-year director Don Thoede is the only person in town who has to get by on a budget of $25,000. Plagued by depth problems (recruiting is tough in a student body for whom practice interferes with SMU rush parties and shopping at NorthPark); just seventy members, tiny for Class AAAAA, so can’t rely on the big play. Thoede’s solution: kilts for drum majors, bright red-and-black uniforms modeled after those of British royal guards for bandsmen, bagpipes for effect. Shrill sound of bagpipes makes band a favorite wherever it plays, even though it lacks punch to win major awards. Scouting report: Corps-style band; old standbys include “Tonight” from West Side Story and selections from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Prospects: Recruiting always a problem and bagpipes a hassle (arrangements are hard to come by and it’s difficult to tune the pipes to the other instruments). But Thoede’s got the flashiest uniforms and the best gimmick in the state.

BEST BAND RIVALRY

Permian High School versus Odessa High School, Odessa. Timing of annual halftime showdown, one day before regional band competition, makes cross-town rivalry even fiercer. This battle of huge (220-plus) bands often more hotly contested than football game, which is usually dominated by Permian. Halftime usually used to be a different story—Odessa placed in the first division in regional marching competition for 37 straight years, second-longest streak in Texas. But last year a triumph for Permian’s ten-year veteran director, Charles Nail, whose squad blew past Odessa en route to finishing second in the state Class AAAAA competition. The big question: Can Permian repeat now that Odessa director Ed Handley had his rookie season under his belt? Scouting report: “Don’t Rain on My Parade” and “My Favorite Things” are Permian favorites; Odessa’s specialties are “Vera Cruz” and “What Kind of Fool Am I?” Prospects: Permian must win consistently to establish tradition, Odessa to regain prestige. In a city where band rivalries start in junior high and parents are even more competitive about it than the band members, the feud will continue to be the best band rivalry in Texas.

BEST WITH THE LEAST

Vega High School, Vega. With only 32 instrumentalists and 8 drummers, the University Interscholastic League’s giant killer. Same plays, same arrangements as larger bands—and so close to same sound that Vega has won Sweepstakes awards (for playing in the first division in concert, marching, and sight-reading competitions) four years in a row. Last year ranked number one in its class in the Sandy Lake Festival poll. The secret behind Vega’s rise to prominence: a farm system that begins in elementary school. Director Isobel Briscoe teaches music and directs the band program for fifth through twelfth grades; she helped mold the current all-star lineup at an early age. Makes up for thin ranks with rigid discipline and marching routines that disguise lack of size. Scouting report: Briscoe’s arrangement of a gospel song medley scored points last year with the home folks and the judges. Theme from New York, New York this year’s highlight, but band is polishing “Tomorrow” from Annie at secret workouts. Prospects: Now a giant as well as a killer. Vega dropped from Class AA to Class A this year, so no longer needs to play David to enemy Goliaths.

BEST ALWAYS-THE-BRIDESMAID BAND

Monahans High School, Monahans. Rookie director Alfred “Buzzy” Green on the hot spot in this marching band hotbed. Took over from revered 22-year veteran Dan Gibbs, the man who put Monahans’ music on the map—fifteen consecutive Sweepstakes awards and two years as the Texas Music Educators Association Honor Band, the equivalent of finishing number one in the polls. Gibbs best known for recruiting (hung up his baton with 274 of school’s 740 students in the band) and scheduling coups (once arranged for a halftime appearance at the Dallas Cowboys’ first game in Texas Stadium). Left Green a full cupboard: the band lost only 65 seniors from the squad that was named outstanding band in its class at the Opryland Music Festival. Substantial budget—$50,000—also gives him plenty to work with. Scouting report: Relies heavily on “Theme From Patton” (almost a second fight song for the school) and “Hawaii Five-O.” Prospects: With its experienced lineup, should be able to compete with any band in the state, even the big-city boys.

BEST BAND EVER

Crockett High School, Austin, 1980. Heartwarming story that fits all the clichés: character in the face of adversity, practice makes perfect, triumph against all odds, and spoils for the victor. Began in despair, with Crockett’s band decimated by crosstown busing—only 96 wind players left, less than half the original number. But band director Paula Crider, the first woman to direct a Class AAAAA marching band, refused to give up. Brought in Randy Bass from the UT band to develop arrangements that turned compact size into an advantage (clear, crisp playing and distinct contrast between soft and loud passages); imposed an exercise regimen to improve marching prowess; preached confidence against bigger opposition—all on a budget of just $5,000. At state competition, up against bands three times its size, Crockett marched to championship score in just four plays. Opened with Earth, Wind, and Fire’s “In the Stone,” followed by “When the Devil Went Down in Georgia” and “Theme From Dallas”; closed with “Malagueña” and, as Crider recalls, “We blew ’em away.” Repeated that victory the following year. Afterward, Crider moved on the UT band department, where she now directs a dozen of her 1980 Crockett band in the UT’s Longhorn Band, the state’s toughest lineup to crack. Her legacy: the memory of a legendary band.

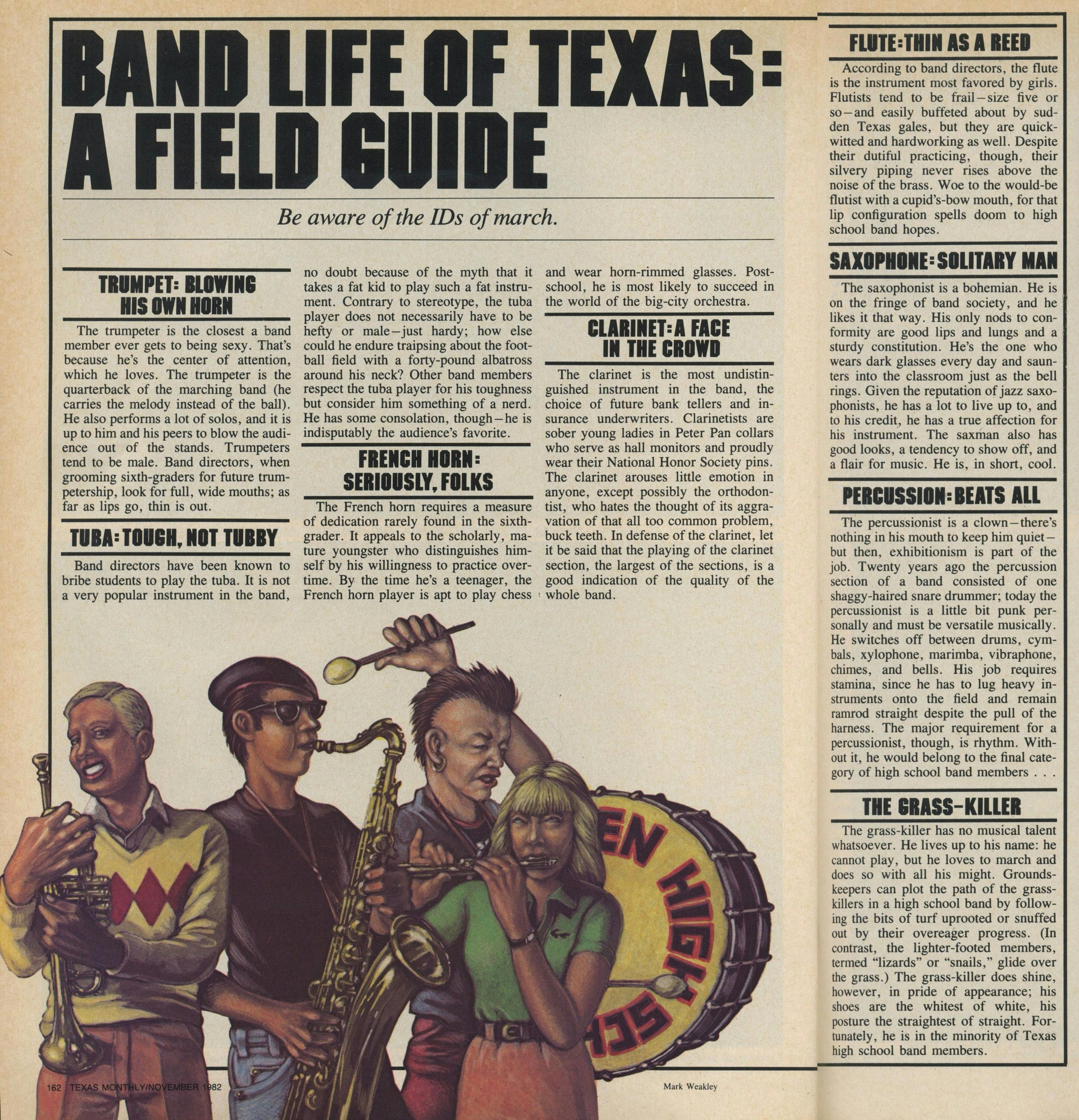

Band Life of Texas: A Field Guide

Be aware of the IDs of march.

TRUMPET: BLOWING HIS OWN HORN

The trumpeter is the closest a band member ever gets to being sexy. That’s because he’s the center of attention, which he loves. The trumpeter is the quarterback of the marching band (he carries the melody instead of the ball). He also performs a lot of solos, and it is up to him and his peers to blow the audience out of the stands. Trumpeters tend to be male. Band directors, when grooming sixth-graders for future trumpetership, look for full, wide mouths; as far as lips go, thin is out.

TUBA: TOUGH, NOT TUBBY

Band directors have been known to bribe students to play the tuba. It is not a very popular instrument in the band, no doubt because of the myth that is takes a fat kid to play such a fat instrument. Contrary to stereotype, the tuba player does not necessarily have to be hefty or male –just hardy; how else could he endure traipsing about the football field with a forty-pound albatross around his neck? Other band members respect the tuba player for his toughness but consider him something of a nerd. He has some consolation, though— he is indisputably the audience’s favorite.

FRENCH HORN: SERIOUSLY, FOLKS

The French horn requires a measure of dedication rarely found in the sixth-grader. It appeals to the scholarly, mature youngster who distinguishes himself by his willingness to practice overtime. By the time he’s a teenager, the French horn player is apt to play chess and wear horn-rimmed glasses. Post-school, he is most likely to succeed in the world of the big-city orchestra.

CLARINET: A FACE IN THE CROWD

The clarinet is the most undistinguished instrument in the band, the choice of future bank tellers and insurance underwriters. Clarinetists are sober young ladies in Peter Pan collars who serve as hall monitors and proudly wear their National Honor Society pins. The clarinet arouses little emotion in anyone, except possibly the orthodontist, who hates the thought of its aggravation of that all too common problem, buck teeth. In defense of the clarinet section, the largest of the sections, is a good indication of the quality of the whole band.

FLUTE: THIN AS A REED

According to band directors, the flute is the instrument most favored by girls. Flutists tend to be frail—size five or so—and easily buffeted about by sudden Texas gales, but they are quick-witted and hardworking as well. Despite their dutiful practicing, though, their silvery piping never rises above the noise of the brass. Woe to the would-be flutist with a cupid’s-bow mouth, for that lip configuration spells doom to high school band hopes.

SAXOPHONE: SOLITARY MAN

The saxophonist is a bohemian. He is on the fringe of band society, and he likes it that way. His only nods to conformity are good lips and lungs and a sturdy constitution. He’s the one who wears dark glasses every day and saunters into the classroom just as the bell rings. Given the reputation of jazz saxophonists, he has a lot to live up to, and to his credit, he has a true affection for this instrument. He saxman also has good looks, a tendency to show off, and a flair for music. He is, in short, cool.

PERCUSSION: BEATS ALL

The percussionist is a clown—there’s nothing in his mouth to keep him quiet—but then, exhibitionism is part of the job. Twenty years ago the percussion section of a band consisted of one shaggy-haired snare drummer; today the percussionist is a little bit punk personally and must be versatile musically. He switches off between drums, cymbals, xylophone, marimba, vibraphone, chimes, and bells. His job requires stamina, since he has to lug heavy instruments onto the field and remain ramrod straight despite the pull of the harness. The major requirement for a percussionist, though, is rhythm. Without it, he would belong to the final category of high school band members…

THE GRASS-KILLER

The grass-killer has no musical talent whatsoever. He lives up to his name: he cannot play, but he loves to march and does so with all his might. Grounds-keepers can plot the path of the grass-killers in a high school band by following the bits of turf uprooted or snuffed out by their overeager progress. (In contrast, the lighter-footed members, termed “lizards” or “snails,” glide over the grass.) The grass-killer does shine, however, in pride of appearance: his shoes are the whitest of white, his posture the straightest of straight. Fortunately, he is in the minority of Texas high school band members.

HIT PARADE

Forget “On Wisconsin.” Here are the modern high school band favorites.

1968: “The Horse”; Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass medley; “Mission Impossible”

1969: “Thus Spake Zarathustra” (theme from 2001: A Space Odyssey); “March Grandioso”

1970: “Aquarius/Let the Sunshine In”; “25 or 6 to 4”

1971: “Hawaii Five-O”; “Theme From Patton”

1972: “Theme From Love Story”; “The Swing March”

1973: “Suicide Is Painless” (theme from M*A*S*H); “Love Theme From The Godfather”

1974: “The Entertainer” (theme from The Sting); “The Way We Were”; “The Sound of Philadelphia”

1975: “Send in the Clowns”; “MacArthur Park”

1976: “Feelings”; “Theme From S.W.A.T.”; Fiddler on the Roof medley

1977: “Gonna Fly Now” (theme from Rocky); “I Write the Songs”

1978: Star Wars medley; “Stayin’ Alive”; “España”

1979: “What I Did for Love” (from A Chorus Line); “Off the Line”; “Over the Rainbow”; “Cordoba”

1980: Superman medley; “Theme from Dallas”; “Let It Be Me”

1981: “On Broadway”; “Through the Eyes of Love” (theme from Ice Castles); “Pictures at an Exhibition”

1982: “Chariots of Fire”; “Georgia on My Mind”; “Aztec Fire”.

- More About:

- Music

- High School

- Richardson