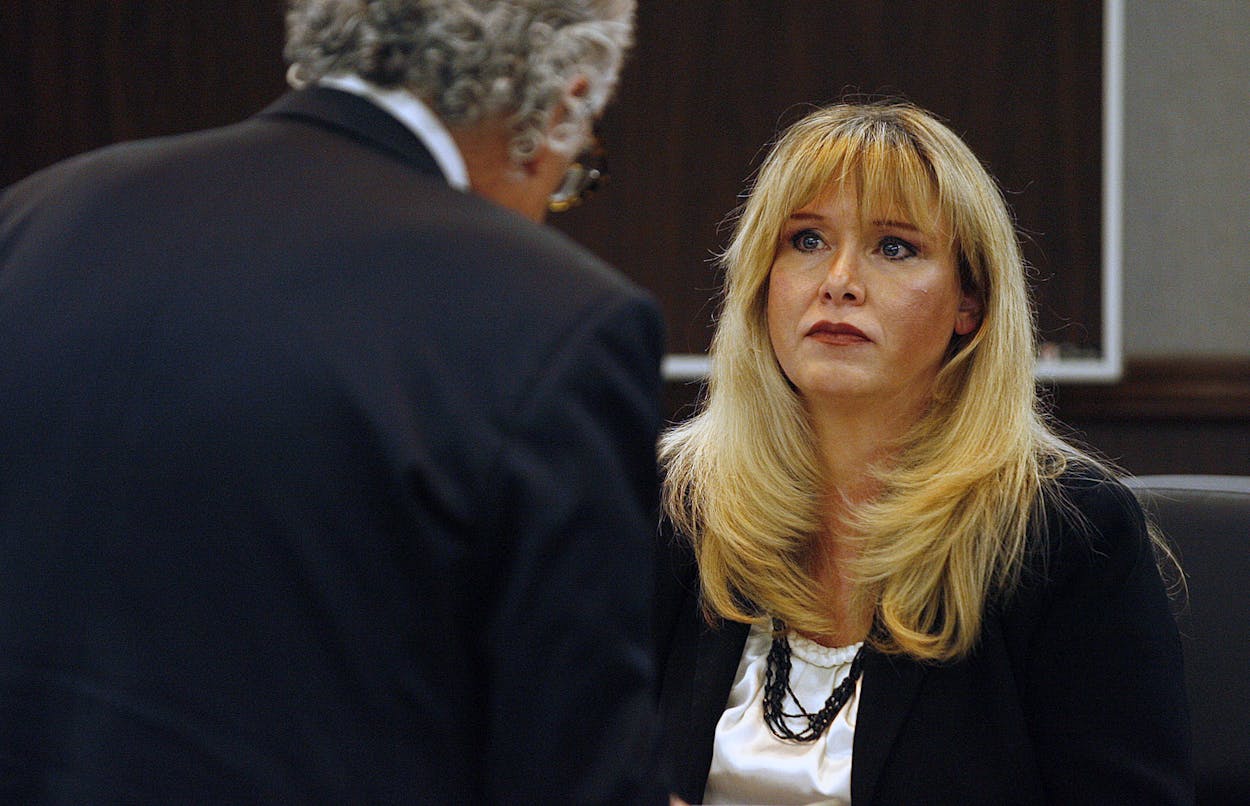

Things took a dramatic turn in Hannah Overton’s evidentiary hearing on Wednesday when ex-prosecutor Sandra Eastwood (pictured above) reluctantly took the stand to be questioned about whether or not she had withheld critical evidence from the defense. The once-confident and commanding assistant D.A., who had aggressively pursued capital murder charges against Hannah in 2007, seemed far different yesterday than she did at trial. Appearing fragile, flustered, and at times on the verge of tears, Eastwood offered up confusing and often contradictory answers as she denied any wrongdoing.

As I noted in my recent article on this case, Eastwood has had a fall from grace since Hannah’s conviction:

Eastwood was fired from the DA’s office in 2010. Then–district attorney [Anna] Jimenez did not publicly disclose the reasons for the termination, but it occurred one week after Eastwood informed her superiors that she had been romantically involved in the past with a sex offender; she reported that she feared the information had been used by the offender’s defense attorney to get him probation in a criminal case. (A subsequent investigation by the attorney general’s office found that no crimes had been committed.)

Testimony yesterday also revealed that Eastwood is a recovering alcoholic who, by her own admission, “was taking prescription diet pills” at the time of Hannah’s trial. “In the evening, I would drink wine because I was very stressed,” she said.

A shouting match erupted between the prosecution, the defense, and Judge Jose Longoria over questions regarding a lunch meeting between Eastwood and Hannah’s appellate attorney, Cynthia Orr. During the lunch, Eastwood allegedly told Orr that her drinking had clouded her memory of the trial. Video of the outburst dominated last night’s local news in Corpus Christi.

But the matter at hand–whether or not Hannah had received a fair trial–is what most of the day was spent exploring.

Under withering questioning from legendary criminal defense attorney Gerry Goldstein, Eastwood repeatedly answered “I don’t know” in response to basic questions regarding whether or not she recognized notes that were written in her handwriting, emails sent from her own email account, and papers signed with her signature. “I have trouble remembering phone numbers,” she said. “I have trouble remembering what I had for lunch yesterday. I think that’s normal. I had hundreds of conversations and there were thousands of documents, so I don’t remember specifics.”

At one point, Goldstein became so exasperated with Eastwood’s evasiveness that he asked her if she remembered the trial itself. “You recall the trial, do you not?” he said, his voice rising. “The individual got life in prison.”

“The question is…?” said Eastwood, flustered.

“Do you remember the trial?” Goldstein asked.

“Yes,” she replied.

“It ended in life without parole!” Goldstein thundered. “That means they spend the rest of their life in prison. You remember cases that have those kind of consequences, don’t you?”

“Yes,” Eastwood said softly.

The former prosecutor became more forthcoming once she was asked whether she had withheld police reports and photos that documented the existence of a critical piece of evidence: a sample of Andrew Burd’s gastric contents from the day that he fell critically ill. The police reports and photos were found in the district attorney’s files last year, by Orr. Hannah’s defense attorneys claim they never saw them before or during trial.

Andrew’s gastric contents would have been highly relevant to the defense, of course, since Hannah stood accused of poisoning Andrew with salt. (Hannah’s defense team had wanted to test the gastric contents for sodium levels before trial, and had repeatedly asked the state to produce them. Whether the gastric contents were deliberately withheld by the prosecution, or simply mislabeled when they were put into the evidence room, was unclear from this week’s testimony.) Regardless, Eastwood was emphatic that she had turned over all the evidence she had to the defense.

As for whether or not she had tried to conceal the medical opinions of Dr. Edgar Cortes, a pediatrician who had treated Andrew–as has been alleged by the defense this week–Eastwood pointed out that she had tried unsuccessfully, at one point late in the trial, to call him to the stand.

In the afternoon, Anna Jimenez took the stand. The former prosecutor, who had served briefly as Nueces County D.A. and assisted Eastwood at Hannah’s trial, did not mince words. “There were things [Eastwood] did that reflected poorly on me and on the district attorney’s office,” she said. According to Jimenez, Eastwood told her, “I will do anything to win this case.” Jimenez also recalled Eastwood sending someone to spy on Hannah’s fellow church members in order to determine what sort of defense strategy would likely be pursued at trial. (Eastwood denied Jimenez’s allegations.)

“Her behavior during the entire course of this trial was so–” Jimenez said, taking a few moments to search for the right words, “–far out.”

Jimenez testified that she had always felt that Hannah should have been charged with a lesser offense, not capital murder. She had taken her concerns over Eastwood’s head, to then D.A. Carlos Valdez, but had been rebuffed.

As for the photos of Andrew’s gastric contents, Jimenez stated that the first time she saw them was roughly a week ago when Orr showed them to her. Jimenez also said that Eastwood had told her that the gastric contents, which the defense had repeatedly asked for, did not exist. “She is not truthful,” she said of Eastwood.

The photos and accompanying police reports constituted “Brady evidence,” Jimenez went on to say–exculpatory or mitigating evidence that the prosecution is required, by law, to hand over to the defense. “The state should have given this information,” she said. “We should have turned this over.” Under questioning from prosecutor Bill Ainesworth, Jimenez conceded that she did not have any conclusive proof that Eastwood deliberately withheld evidence from the defense. But, she added, “It’s like any other criminal issue when there’s circumstantial evidence. We prove cases in court every day on this same kind of evidence. When you look at the fact that [the defense] asked, and asked, and asked for this evidence, and we did not turn it over, and [the medical examiner’s office] tested it … that meant there was some, and we didn’t give it to them.”

Indeed, the Nueces County medical examiner, Ray Ferndandez, did test Andrew’s gastric contents, but apparently mislabeled and mixed up the samples, therefore rendering the test meaningless. It is thought that Fernandez may be called to testify on Thursday.