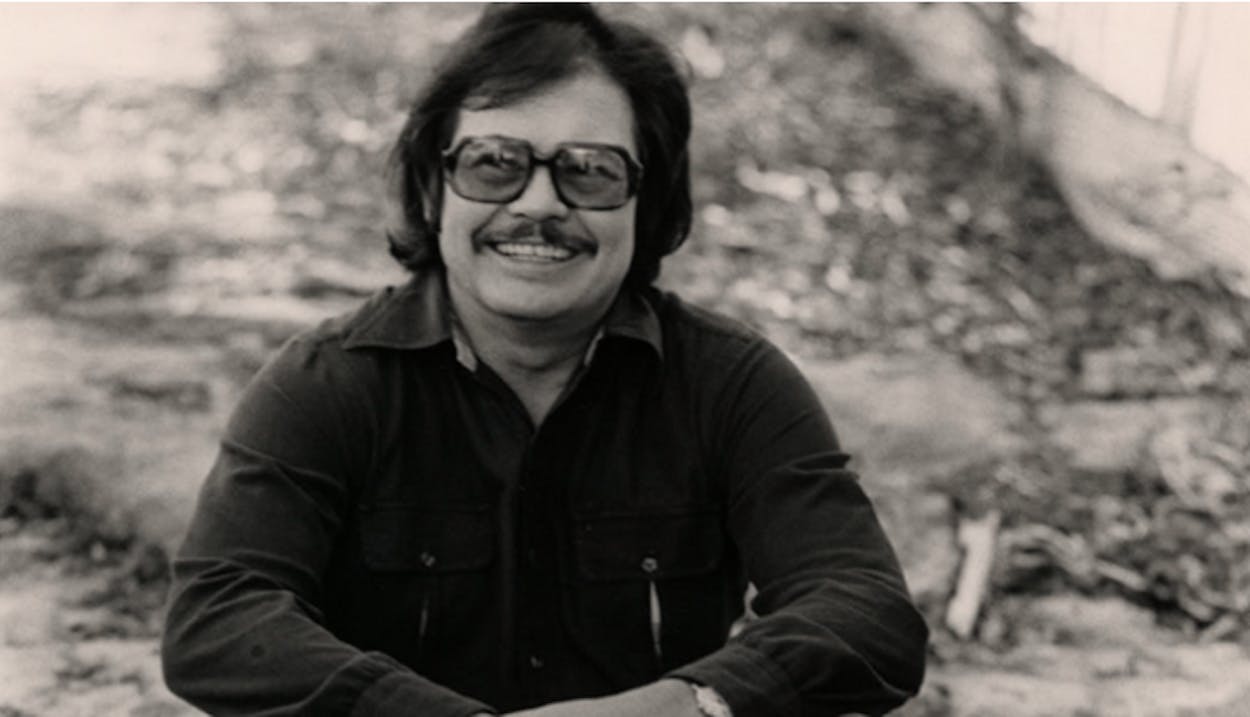

Gary Cartwright retired from Texas Monthly in 2010, but his presence still looms large in the magazine’s halls. And for good reason. Cartwright was one of the first writers to work at Texas Monthly, and in his four-decade-long tenure covering the state for the national magazine of Texas, his body of work could serve as a sort of reference guide to the state’s history. He wrote about nearly everything relevant to the Texan experience, from larger-than-life characters like “Dandy” Don Meredith and the infamous Jack Ruby to famous battlegrounds, injustices in the legal system, and underground subcultures. His style of writing influenced a generation, and some of the current writers quite literally carry photocopies of Cartwright stories in their bags, something that no doubt secures his reputation as “The Best Damn Magazine Writer Who Ever Lived.”

To celebrate Cartwright’s eightieth birthday on August 10, Texas Monthly staffers have chosen their personal favorites of his stories. (And find out a bit more about the man, in his own words, here.)

Mimi Swartz, Executive Editor

Growing Up Fast (1982)

Nothing to It (1997)

I love these stories about Gary’s sons Shea and Mark even more than his crime and sports stories. They show another side of him, and another side of his gift. In both pieces he writes about his struggles to define fatherhood in a way that is both so intimate and so universal — his love shines through. The fact that his son Mark worked for the magazine for so many years makes the subject even more powerful for me, but I think that anyone who reads them can’t help but be profoundly moved.

David Courtney, The Texanist

Candy (1976)

It’s probably not unusual for an introduction to the great Gary Cartwright to be a memorable occasion. Mine was unique in that the first words I ever heard him speak happen to have come from his story about the legendary Texas stripper Candy Barr. When read from the page of a magazine the lines are striking enough, but when they come into your ear straight from the lips of their author they will be forever emblazoned upon your brain.

At an event commemorating the donation of the Texas Monthly archives to the Southwestern Writers Collection in San Marcos, Gary chose to read from ‘Candy’: ‘On the road home from Brownwood in her green ’74 Cadillac with custom upholstery and the CB radio, clutching a pawn ticket, for her $3000 mink, Candy Barr thought about biscuits. Biscuits made her think of fried chicken, which in turn suggested potato salad and corn.’ Gary pronounced ‘corn’ like ‘karn.’ He went on: ‘Two hours later, Candy was still dressing. When she finally made her appearance, shortly before 10 p.m., she hit the room like one of Sgt. Snorkel’s ping-pong smashes. Her blonde hair was in curlers. She had scrubbed her face until it was blank and bleached as driftwood. Her green eyes collapsed like seedless grapes too long on the shelf. She wore a poor white trash housedress that ended just below the crotch, and no panties.’

I was immediately sold. I’ll never forget it. Thank you, Gary. And happy eightieth birthday to you.

Katy Vine, Senior Editor

Leroy’s Revenge (1975)

Leroy’s Revenge has got to be one of the most disgusting, riveting stories we’ve ever published. It’s not a story you put down and pick up again, although it might be a story you throw across the room and pick up again.

Nate Blakeslee, Senior Editor

Leroy’s Revenge

One of the all-time best last lines in magazine journalism.

Pamela Colloff, Executive Editor

The Longest Ride of His Life (1987)

This is a riveting, beautifully constructed story that lays out the evidence that Randall Dale Adams was innocent of the crime that earned him a capital murder conviction and death sentence. Adams was later freed and exonerated, but when Gary wrote this story, he still had a death sentence hanging over his head. The end of the piece still gives me goosebumps.

David Moorman, Associate Editor

Is J.J. Armes for Real? (1976)

This was the first story by Gary Cartwright that I worked on [as a fact checker]. Although I did my best to verify and confirm every detail as he had written it, there were several things I was unable to run down by the time we went to press — and by then the subject was no longer cooperating with the reporter.

For instance, the interior decoration — ‘Entering Jay Armes’ mansion is yet another trip beyond the fringe: it is something like entering the living room of an eccentric aunt who just returned from the World’s Fair. There is a feeling of incongruity, of massive accumulations of things that don’t fit, passages that lead nowhere, bells that don’t ring. We wait in what I guess you would call the bar. The décor might be described as Neo-Earth in Upheaval.’

In almost every Cartwright story he makes mention of some animal. He may initially have been attracted to the bizarre world of Jay Armes when he learned that the private eye had his own menagerie of exotic animals. As for the pet elephant that Jay Armes once supposedly owned — I never was able to ascertain that one of his neighbors had shot it with a crossbow. But we all understood the poignancy and richness of that detail, and we decided to publish it anyway.

John Spong, Senior Editor

Main Squeeze Blues (2006)

If Yankee Stadium is the House that Ruth Built, Texas Monthly is the Magazine that Gary Cartwright Built. For all the noted writers who have appeared in the magazine, Cartwright has always been the standard the rest have had to strive to match. His voice — authoritative, insightful, funny, and sometimes just plain weird — established our tone, and the exquisite simplicity of his sentences created Texas Monthly’s reputation as a writer’s magazine.

And it’s as tough to imagine Cartwright without the magazine as it is the other way around. He’s lived his life in our pages, used them in lieu of a therapist’s couch or a church confessional as a place to examine the various victories and defeats of his own existence. He could be goofy (‘I Am the Greatest Chef in the World’), heartbroken (‘Nothing To It’), and shockingly, delightfully revealing (‘How to Have Great Sex Forever,’ about his own battle with erectile dysfunction and grateful discovery of Viagra). In 2006, still reeling from the death of his wife of twenty-nine years, Phyllis, he wrote “Main Squeeze Blues.” It’s a beautiful valentine to the great love of his life, a woman he describes in the piece as a ‘stunning and curvaceous high-kicker who’d once twirled flaming batons for the Wetumka High band.’ At the story’s end he sits in their living room with their Airedales, sifting through the pain to couple each pang of loss with little bits of love, appreciation and hope. And if you’re not crying when it’s over, then you must never have been in love yourself.

Other essentials:

Who Was Jack Ruby? (1975)

The Endless Odyssey of Patrick Henry Polk (1977)

Free to Kill (1992)

The Innocent and the Damned (1994)