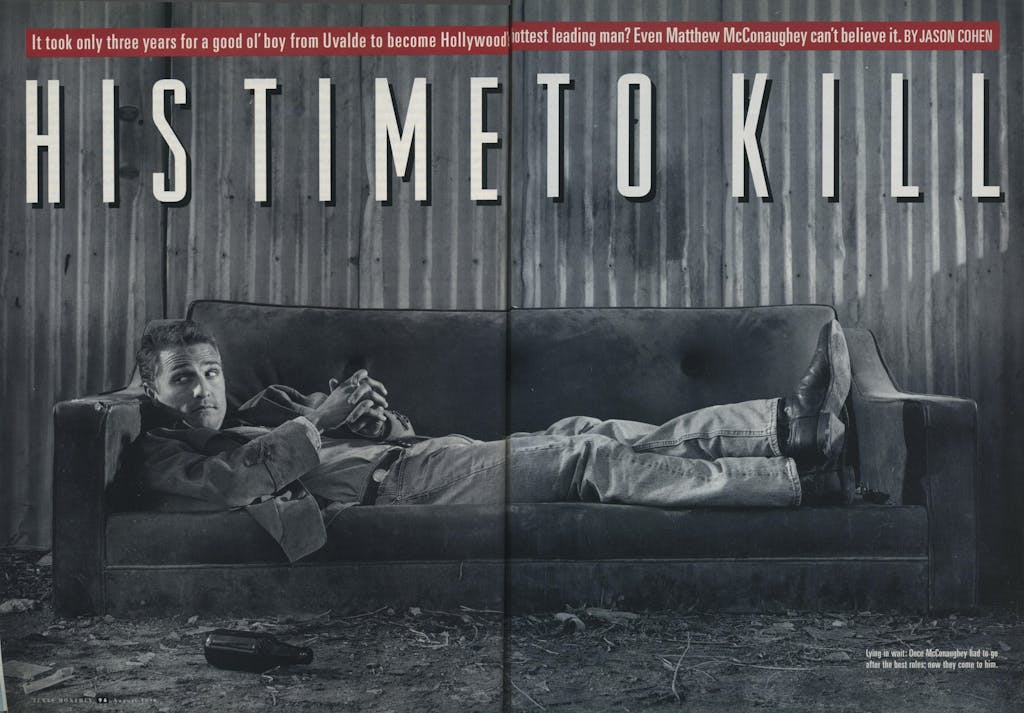

POPULAR CULTURE IS DETERMINED BY THE POPULACE. No matter what America’s corporate entertainment machine puts in the theaters, the public can always reject it. But in this age of $100 million budgets, the movie companies do everything they can—surveys, focus groups, demographics studies, micromanaged ad campaigns—to determine what will put paying bodies in the cineplex seats. Sometimes they actually get it right, and a solid product and marketing align in such a way that the studios just know something is a hit. Or that someone is a star. For while most moviegoers don’t know what he looks like and his big turn is only now hitting theaters, the verdict has been in for months: Matthew McConaughey is a star.

In April the 26-year-old Uvalde native, a veteran of Austin filmmaker Richard Linklater’s Dazed and Confused ensemble, was one of three up-and-comers featured on the cover of Vanity Fair’s annual Hollywood issue. He was the one who wasn’t Tim Roth or Leonardo DiCaprio. The reason for this prime placement was McConaughey’s unexpected casting in A Time to Kill, the latest adaptation of a book by John Grisham, America’s best-selling thriller writer. The racially charged legal cliff-hanger turns on the rape and beating of a ten-year-old African American girl; when her father enacts a murderous revenge upon the white men responsible, his fate becomes a matter of life-or-death-penalty for his lawyer, Jake Brigance. The heroic, conflicted role of the young defense attorney was one that every youngish actor coveted, so the movie world was caught off guard when the plum went to someone with such a slim résumé. Hollywood being Hollywood, the town recovered from its surprise and immediately coronated the actor with “It Boy” status.

Here’s a sample of Matthew McConaughey’s press clippings these past few months: When the most important talent agency in town, Creative Artists (CAA), parted ways with Sylvester Stallone and Kevin Costner, the editor in chief of Variety said its relationship with McConaughey helped make up for those losses. Grisham (who, granted, is biased) described him as a cross between a young Newman (a McConaughey hero) and a young Brando. Not to be outdone, the New York Times added Gregory Peck to the mix. And Vanity Fair made an unprecedented move—Matthew McConaughey, though not yet a household name, is on the cover, solo, just four months after his previous cameo. And he’s not even pregnant or naked.

McConaughey (pronounced “Muh-con-uh-hay”) is just enjoying the play, especially when the phone calls come, promising no-audition roles and dollar figures he has never seen before. “I’m looking at these offers and going, ‘Really?’” he says, chuckling. “I have more options, and options are power, which is good if you use it in the right way.”

McConaughey knows he caught a break, but he never doubted it would come eventually. When A Time to Kill was screened for test audiences, the response was 500 “excellents” out of 509 cards, a staggering, near-impossible level of approval. “The research people had never seen anything like it,” Joel Schumacher, the movie’s director, says. Previously responsible for, among other things, St. Elmo’s Fire with a then-unknown Demi Moore and Flatliners with a then relatively unknown Julia Roberts, Schumacher is the man who made McConaughey’s breakthrough possible. A year later, he couldn’t be more effusive about his choice: “I don’t think Matthew was lucky to get this role,” the director says. “I think I was lucky to get Matthew.” Pretty soon, lots of other producers, directors, and studio execs will be saying the same thing.

MATTHEW MCCONAUGHEY IS, as he puts it, “in business mode.” It’s April, and the release of A Time to Kill is three months away. But it’s no longer acceptable for an actor to leave his career in other people’s hands. He can’t just show up, read his lines, and spend the rest of his time chaperoning starlets and avoiding paparazzi.

A few months ago he switched agencies, from William Morris to the more high-powered CAA, and he has brought his friend Gus Gustawes, a UT buddy with a graduate business degree, out to run his production company. Their operation is j.k. livin productions, named for one of McConaughey’s lines in Dazed and Confused (“You just gotta keep on livin’”). Eventually they will produce outside projects in addition to serving as the primary vehicle for McConaughey’s work as a writer-director and an actor. A studio is bound to bankroll their venture soon, but at the moment the two men are on their own, taking two or three meetings a day and working out of a living room littered with red paperbound scripts bearing the CAA logo.

Today is Sunday, however, so while they still answer the phone “j.k. livin productions” out of habit, this is an afternoon for peeling off shirts and cracking open Bud Lights by the beach, which happens to be the back yard. McConaughey’s house is not plush, nor is it on a truly decadent shoreline stretch, but it still makes you realize why people live in Los Angeles, the picture-window Pacific view on a cool blue-sky day making up for a whole lot of smog, gridlock, and narcissism.

McConaughey is hosting a small gathering of neighbors and friends. It’s a laid-back crowd, even if one of the gang—a cute, slender, vaguely familiar brunette McConaughey introduces as “Sandy”—is more or less the world’s biggest young female star. Sandra Bullock (or “Redblood,” as McConaughey calls her) is also in A Time to Kill. She plays a law student who provides McConaughey’s character with legal assistance and romantic temptation.

With a blue bandanna tied around his head, aviator shades masking his deep blue eyes, and a wispy goatee, McConaughey resembles the original FBI sketch of the Unabomber. He takes exception to this comparison, but his friends rib him about it anyway. A plug of Levi Garrett chaw is visible in his upper lip. When he was briefly involved with another A Time to Kill co-star, Kentucky girl Ashley Judd, they chawed together. “The great part about Matthew,” Joel Schumacher says, “is he’s the kind of guy every mother would like their daughter to marry, but there’s also a badass, bad-boy side to him. It creates a wonderful tension on screen.” John Mellencamp, McConaughey’s absolute favorite, is cranking from the stereo. Later in the summer, he excitedly reveals, he’s going to appear in the rocker’s new video. The talk on the balcony is of golf (a passion) and boating and Texas—McConaughey’s home state is well represented in his decorating scheme, with a stuffed Longhorn mounted on the deck, a UT clock in the living room, and a marked-up highway map from a recent Texas-New Mexico road trip in the stairwell.

Next door, a much larger party fills the beach—it’s Eastern Orthodox Easter, and McConaughey’s Greek neighbor has roasted a lamb and invited a few hundred close friends. Renée Zellweger, herself a Texas actress with an imminent career-making role opposite Tom Cruise in Jerry Maguire , drops by. At first she mistakes the next-door scene for McConaughey’s house, and she tells him she feared he had “gone Hollywood” on her.

The gang makes its way to the beach, but there’s a problem—being in a semi-public place with Sandra Bullock. People with cameras automatically gravitate to the space around her. This is how Hard Copy gets those casual shots of “partying” celebrities. McConaughey’s friends close ranks around Bullock, getting between her and the lenses. Nobody wants to take a picture of Matthew.

AUSTIN’S HYATT REGENCY will never be confused with Schwab’s drugstore, but that’s where Matthew McConaughey had his Lana Turner experience—where he was touched by the hand of celluloid fate. In the spring of 1992 the UT film student was in the hotel bar with his girlfriend when the bartender pointed out a gentleman who was apparently in the movie business. McConaughey introduced himself to Don Phillips, and over several hours and several drinks the two men talked film and golf, until they became so loud that the Hyatt’s management bid them a forceful farewell.

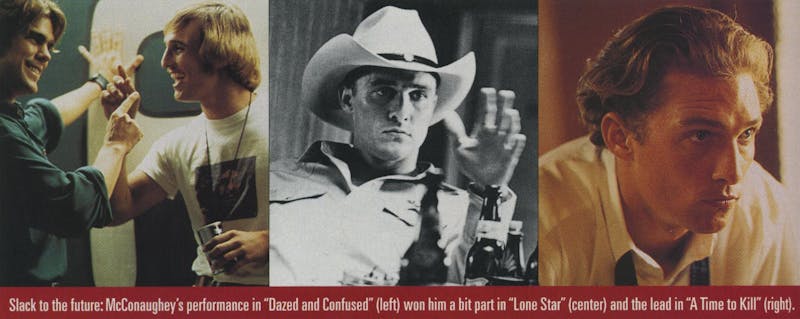

Back at McConaughey’s house, Phillips revealed his bona fides: He was a casting director, and having put unproven talents like Sean Penn and Jennifer Jason Leigh and Forest Whitaker in Fast Times at Ridgemont High a decade before, he was now rounding up prospects for Linklater’s similarly subversive seventies high school comedy, Dazed and Confused. He thought McConaughey would be a good fit for Wooderson, the mustachioed, bleached-blond relic who can’t let go of high school good times—or high school girls. Linklater’s improvisational style allowed his young cast room to roam, and McConaughey’s small role evolved into a memorably hilarious part with screen time right up to the final scene.

Suddenly, acting seemed like a logical pursuit, but first McConaughey finished film school—his UT diploma hangs in a massive frame above the fireplace in his upstairs bedroom—and shot a documentary, Chicano Chariots, about lowrider car culture in Texas. With Phillips’ encouragement, he was headed for Hollywood, but first he read for a small part in the still-unreleased Return of the Texas Chainsaw Massacre. He didn’t get it. Instead, writer-director Kim Henkel offered him the villainous lead role, opposite Renée Zellweger.

In August 1993, McConaughey arrived in Los Angeles, still on a roll. The William Morris Agency took him on as a client, and his first audition landed him the most significant male part in the “woman’s picture” Boys on the Side, which won him recognition beyond Dazed and Confused. But then the fairy tale took an intermission. McConaughey felt his auditions were sluggish and passive, and he lost out on hot parts in The Quick and the Dead, Assassins, and The Great White Hype. So he went back to his original love, directing. He put together a twenty-minute short called The Rebel, a comedy about a guy who thinks life on the edge means taking eleven items through the supermarket express checkout.

“That was the best thing I ever did for my acting,” he says. “Having a thing on the side that I really had a lot of pride in helped me a lot.” Possibilities began to open up, but aside from a couple of small roles—most notably his crucial part in John Sayles’s Lone Star, which critics have already placed next to Giant and The Last Picture Show as a grand, archetypal Texas movie—nothing he was excited about. Looking back, he gratefully notes that anything he might have done at the time would have interfered with his availability for A Time to Kill.

A Time to Kill was being made by the same production company and studio (Regency and Warner Bros.) that did Boys on the Side, and director Joel Schumacher was aware of McConaughey’s work. In April 1995 McConaughey went to see Schumacher on the set of Batman Forever, which Schumacher was directing, and talked to him about a supporting part in A Time to Kill eventually taken on by Kiefer Sutherland; but in reading the book, McConaughey had taken a liking to Grisham’s semiautobiographical hero, so while visiting with Schumacher, he took his shot.

“I’d heard Brad Pitt was playing the part, so I said, ‘Is Brad playing Jake?’ and Joel said, ‘No, do you think he should?’” McConaughey recalls. “And I go, ‘No, I think I should,’ and he and I looked at each other, just started smiling, and he said, ‘You know, you’d be a great Jake, but there’s no way the studio is gonna go for it.’ We laughed, and that was kinda it.”

Schumacher says he liked McConaughey for the lead all along, but this was a John Grisham movie—Tom! Julia! Denzel! Tommy Lee!—so an established star seemed inevitable. But he couldn’t cast the part without John Grisham’s say-so. Grisham, who still considers his 1989 debut novel to be his best work, refused to sell the movie rights until he got a director he liked—Schumacher’s The Client was the only adaptation he enjoyed—and cast approval. For a year, the two men hadn’t been able to settle on anyone, so Schumacher told Grisham he had a dark horse. “I knew you were hiding something!” Schumacher remembers the novelist saying. “You brought up all these names of all these terrible actors I hate because you had a secret casting surprise for me!”

Schumacher put together a screen test for McConaughey and in May summoned him to California from the set of Lone Star in Eagle Pass. McConaughey did his scenes on a makeshift set with a small crew. A few days later in Virginia, John Grisham and his wife watched this anonymous performer deliver the climactic courtroom summation. Then they watched it again.

Warner Bros. was so relieved that their two artists had finally agreed on something that the studio didn’t raise any objections. McConaughey has his own theories on that one. “There are a lot of things that happened that allowed me to get in there,” he says. Namely, the built-in draw of Grisham and the newfound power of Bullock, whose While You Were Sleeping made her one of those rare female leads who could “open” a movie by herself. The rest of the supporting cast is made up of well-liked, high-intensity actors, including Samuel L. Jackson, Donald and Kiefer Sutherland, and Academy award winners Kevin Spacey and Brenda Fricker. “The movie is not on my shoulders,” says McConaughey, who was paid $200,000 for his part.

He was back to work in Eagle Pass when he heard the news. “I get the call and it’s Joel and John Grisham,” he remembers. “Grisham goes, ‘Matthew, let’s make a movie together.’ I was out of my head. I coughed a lot. I said ‘F yeah!’ about thirty times.” He immediately sought out Lone Star’s still photographer: “I said, ‘Take some pictures of me right now. I’m glowing and I have a good reason to be glowing and I want to see what I look like.’ So he took some shots, and I’ve seen ’em and my cheeks are hot. I’m just electric.”

ASK MOST SHOW BUSINESS PEOPLE these days who their movie heroes are and you’ll get a Quentin Tarantino—like laundry list of old-time matinee idols, suitably obscure auteurs, and action directors. But not Matthew McConaughey—besides Paul Newman, his only other cinematic hero is noted thespian Lou Ferrigno. “The Incredible Hulk, yeah,” he says, grinning. “He turned into the Hulk twice a show, and he’d always throw those big air tanks.”

Entertainment wasn’t on the agenda in McConaughey’s working-class family. “We weren’t allowed to watch much TV,” he says. “The rule was, if there was daylight, you were outside, building tree houses, frog gigging, riding bike trails, stuff like that. At night, okay, an hour of TV, then let’s play a board game.” McConaughey was the youngest of three children, and he was also an accident: Unable to conceive a second child, his parents had adopted a son, Pat, as a tenth birthday present for their eldest, Rooster (Mike on his birth certificate). Six years later, Matthew came along.

His father, “Big Jim” McConaughey, was, in his son’s words, “a coonass from Louisiana.” He spent a year with the Green Bay Packers after playing college ball at the University of Houston and (for one year) at Kentucky for Bear Bryant. Big Jim ran a Texaco station in Uvalde, but in 1980—boom time—he moved the family to Longview and went into the pipe business. McConaughey’s mother, Kay, was a Trenton, New Jersey-born schoolteacher, and in the course of 39 years she and Big Jim were twice divorced and twice remarried (Big Jim died in 1992). Nevertheless, it was a fairly religious, no-nonsense family with a few simple rules: no lying, no back talk, and, McConaughey remembers, “You could never say ‘I can’t.’”

At UT he was going to get a liberal arts education and then he was going to law school. “The family always said, ‘Yeah, you need to become a lawyer and then come and get us all out of trouble,’” he says. “But it wasn’t tickling my gut. I wasn’t waking up every day thinking, ‘Man, I can’t wait to get to law school.’”

An epiphany was just around the corner. Well, lying on the coffee table at a friend’s house, actually. McConaughey, who says he never read a book cover-to-cover until college, was killing time before his sophomore final exams when he spotted the paperback that changed his life: The Greatest Salesman in the World, a multimillion-selling tome by Og Mandino, who was a sort of Dale Carnegie-M. Scott Peck figure in the sixties and seventies.

“My first reaction was, ‘That’s a really aggressive, corporate-capitalistic title,’” McConaughey says, “but it was philosophy, it was self-improvement, and it was very, very practical.” (Among the book’s mantras: “I will laugh at the world” and “I will act now.”) McConaughey keeps multiple copies around the house for himself and for anyone else he encounters, including journalists. He was struck by “the fact that I had found it, that it found me, it wasn’t a book that somebody said, ‘You must read this.’ The next day I ripped up my fall schedule and decided I wanted to tell stories.”

A TIME TO KILL AND LONE STAR are not the only movies McConaughey appears in this year. Before either of those films began shooting, he landed a small part in Larger Than Life, a man-meets-elephant comedy starring Bill Murray. During the post-Boys on the Side downtime, McConaughey auditioned for the part of Tip Tucker, an obnoxious, pill-popping trucker who picks up Murray and the elephant hitchhiking. “I went and got this ugly green stretch-material jersey, stuffed it, pulled my American flag cap on all bowed over, put a big ol’ dip in, and just had fun,” he says. He had to tone it down, though, after Murray made a crack about the movie’s needing subtitles.

That was then. Now McConaughey is a commodity, and new scenes are being added to Larger Than Life. It’s eight days after the Sunday beach party, and this morning a driver came at five o’clock to take McConaughey to the location. In makeup, one of the film’s producers, John Watson, comes to pay his respects. Watson mentions the dramatic justification for the new scenes: Late in the film, the “conflict” between Murray’s character and the elephant has been “resolved” (i.e., Bill has gotten over his irritation with the unwieldy creature and learned to love it), so the return of Matthew’s angry trucker gives the story a shot in the arm. Plus, the producer says “the cards” were through the roof, the preview audience loudly declaring that Tip Tucker’s eight minutes were the best part of the movie. Throw in the equally overwhelming results of A Time to Kill’s test screenings, and the new scenes and delay in opening Larger Than Life until after McConaughey’s starring debut make sense.

McConaughey is glad to be working and pleased that he’ll be seen in this comic role after his more serious work in A Time to Kill. He doesn’t want to be pigeonholed; he wants to move between genres, to be a leading man and also do character parts. “There’s two kinds of actors,” he says. “Some actors have a certain characteristic. You just like ’em, they’re movie stars, and you always know it’s them. Then there’s someone like Gary Oldman or Sean Penn, who can completely humble himself. They erase everything to become a certain character. I’d like to incorporate both.”

Exactly what movie McConaughey might do that in is the question—one that’s very much on his mind as he works on Larger Than Life. In between quick takes and little actorly adjustments—“Did my ass stick out enough?” he asks the director, who assures him that it did—McConaughey is on his cell phone, checking with Gus for a career update. “In the next hour,” he says, “the year could be entirely planned. Or it could take another four months.” Well, it took more than an hour but less than four months: By June, McConaughey’s future was mapped. Because he has a two-picture option with Warner Bros. as part of his deal for A Time to Kill, he had to pass on a remake of The Day of the Jackal as well as the sequel to Speed. Another project, the Texas bank robber saga The Newton Boys, from Texas screenwriters Claude Stanush and Clark Lee Walker and writer-director Linklater, has been back-burnered but remains a likely prospect.

The movie he will make for Warner Bros. couldn’t be more ideal. McConaughey will yield the top of the marquee to Jodie Foster in Contact (he’s being paid a reported $4 million), a sci-fi action epic that will be the first post-Forrest Gump effort from director Robert Zemeckis. As with A Time to Kill, McConaughey shares the heat with a high-level female star and with a director who has been responsible for some of Hollywood’s grandest (and highest-grossing) commercial entertainments—not just Gump, but also Who Framed Roger Rabbit and the Back to the Future and Romancing the Stone series. There’s even talk of Paul Newman’s joining the cast in a supporting role. Naturally, McConaughey says he’d rather be the first Matthew McConaughey than the next Paul Newman, but he probably didn’t foresee the day when he could be billed above his blue-eyed idol, either.

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Longreads

- Matthew McConaughey

- Uvalde