The tiny town of Ingleside on the Bay occupies about a third of a square mile of sand across the water from Corpus Christi. It is known primarily for its nearby shipping traffic, a closed naval station, and rustling palm trees; its 615 citizens are a placid bunch of retirees, Canadian snowbirds, shrimpers, and championship Bunco players. But in the past year, the hamlet has become a battleground, as Marty Rathbun, an ex-Scientologist who moved here in 2006, has tangled with a group of self-appointed defenders of his former religion. In the process, the town’s residents have found themselves at the center of one of the strangest religious dustups in America.

Scientology has long captured popular imagination with its Hollywood Boulevard personality tests, cosmic belief system, and celebrity followers such as Tom Cruise and John Travolta. The religion was founded by science fiction writer L. Ron Hubbard in 1952, and according to the Statistical Abstract of the United States, the Church of Scientology has around 25,000 adherents nationwide. Under its ecclesiastical leader, David Miscavige, the church has become a powerful entity, with tentacles that reach as far as Taiwan and a 440-foot cruise ship that roves the Caribbean. It does not take kindly to defectors. A church dropout who continues to practice Scientology in unauthorized ways is termed a “squirrel” and is investigated, lest he or she become, as Hubbard once wrote, “the implanter, the warmonger, the wrecker.”

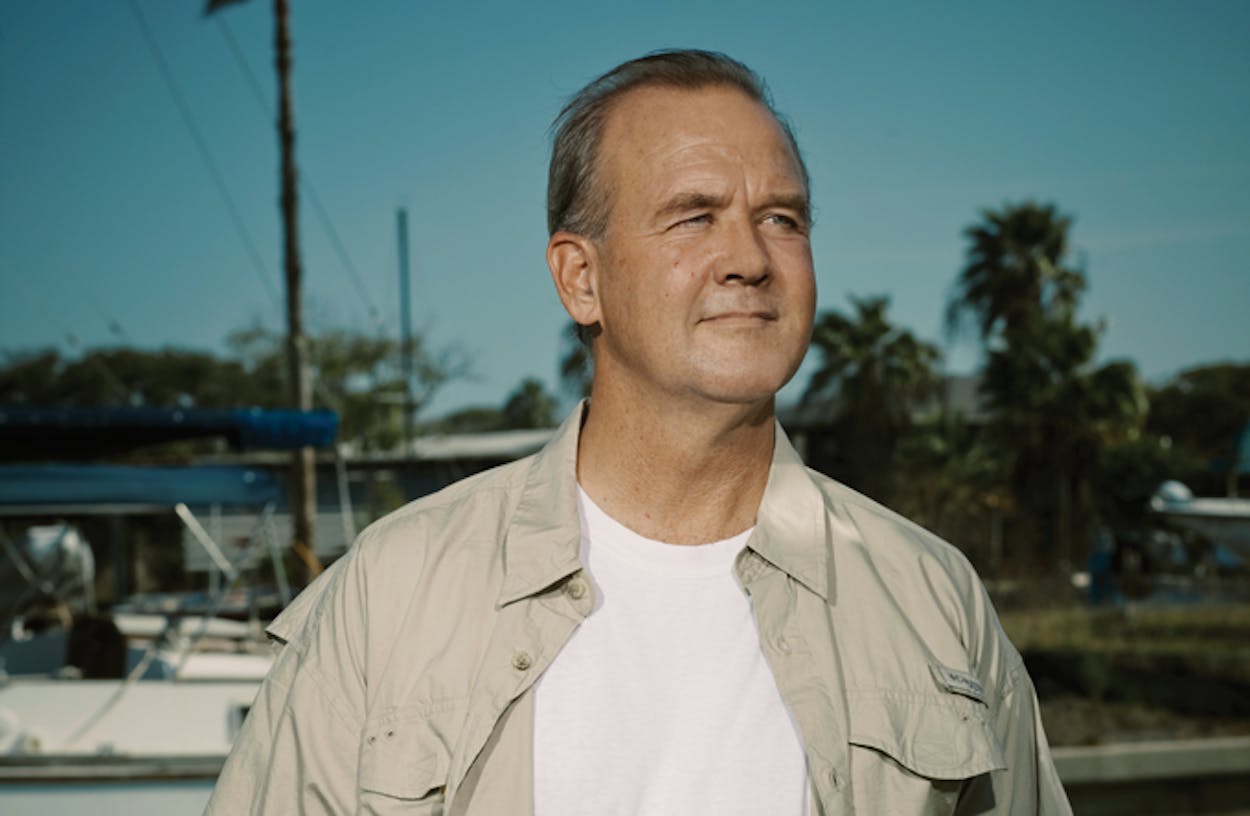

One of the most well-known heretics is Rathbun, a 55-year-old from California who spent 27 years in the church and rose to the rank of inspector general of the Religious Technology Center—a position directly under Miscavige—before leaving in 2004. A few years later, Rathbun, whom the church describes as a “defrocked apostate” who was expelled for malfeasance, began giving damning interviews about the institution to, among others, the St. Petersburg Times, the Village Voice, Anderson Cooper, and the New Yorker. In February 2009 Rathbun launched a blog, labeling himself an “independent Scientologist” and offering counseling to fellow defectors, who began flocking to his doorstep from around the world. All of this was seen as an egregious violation by the church, which has publicly condemned Rathbun’s actions.

In Ingleside on the Bay, residents neither knew nor cared much about Scientology when Rathbun moved to town. But as his notoriety grew—he says his blog got 2.5 million hits in 2011 alone—he attracted the attention of Squirrel Busters Productions, a band of filmmakers who made it their mission to expose his unsanctioned Scientology practices. (The church denies an association with the group, saying it is an independent production company.) The town was quickly overrun: SBP crews began following Rathbun in April 2011, filming him in the street, trailing him into restaurants, and confronting him at the airport and his house. Local radio ads cautioned listeners about Marty “the Squirrel” Rathbun. Residents found 41-page “neighborhood alert” booklets affixed to their front doors.

For six months, Rathbun’s neighbors witnessed daily filming sessions, which sometimes included shouting matches between Rathbun and the Squirrel Busters. (The group posted the exchanges on its YouTube channel, SquirrelZone.) In September, standing a legal ten feet from Rathbun’s yard, a two-man crew held a camera as a reporter read “breaking news” from cue cards. Wearing a black baseball cap and a T-shirt emblazoned with an image of Rathbun’s face on the body of a squirrel, the woman accused Rathbun of having a drinking problem. (Rathbun was arrested in New Orleans in July 2010 for public drunkenness; the arrest was expunged.) Also, she continued, he had no regard for his wife as a woman. “We know that from the type of sex toys in his collection,” she stated gravely.

The Squirrel Busters presented themselves as documentarians, and aggrieved ones at that. Earlier in the summer, John Allender, a producer for SBP, told the Corpus Christi Caller-Times that Rathbun was fostering a “hate campaign against his former religion” and that SBP was making a documentary to chronicle his harmful influence. (Allender did not return calls for this story.) But as filming turned increasingly into what Rathbun considered harassment, residents of Ingleside on the Bay found themselves officially caught in the middle. Sheriff’s deputies became inundated with competing calls from Rathbun and SBP, with both parties offering video evidence of the other’s transgressions.

For the most part, though, the town seemed to close ranks around Rathbun. In 1991 Ingleside on the Bay fought a proposed annexation from neighboring Ingleside and incorporated with a popular vote; as Jim Isbell, a retired research scientist, told me, citizens are rigorous about their rights. “Look, I’m not a member of Marty’s religion. I’m a Lutheran,” said the 75-year-old, who runs the local tea party group. “But I am a believer in the First, Second, Fourth, and Tenth Amendments. And the Squirrel Busters are trying to take away Marty’s right to free speech.” A petition to stop SBP from filming was circulated. Yards sprouted signs forbidding the entry of Squirrel Busters. Residents whispered about a film-interrupting plot involving popcorn and seagulls. Rathbun’s next-door neighbor, 70-year-old Charlie Orr, ambushed the crew by turning his sprinklers on them. (They returned wearing raincoats in the 100-degree heat.)

“You gotta understand,” said Christian Wiseman, the owner of a local steakhouse, Nightlinger’s Chuck Wagon. “There is nothing going on in this town. Nothing. This place is wallpaper, man. So the paparazzi tactics, the cars with cameras all over them, the cloak-and-dagger stuff, it was wild. By the way, have you watched the videos? Comedy gold.”

A city filming ordinance was created, only to be rescinded after SBP retained a lawyer. (The county attorney found nothing illegal in SBP’s activities, and Mayor Howard Gillespie explained to me, “I don’t like the Squirrel Busters being here, but they have their rights too.”) In July, as residents’ exasperation grew, a spirited public hearing was held—the most-attended town hall meeting in years and, naturally, one recorded by SBP—during which Rathbun volunteered to leave town when his lease expired, in November.

Isbell was among those who urged him to stay. “This is Texas, and we got here in wagon trains,” he told Rathbun. “Not all the cowboys agreed with each other, but when the Indians attacked, they got in a circle. And all the guns were pointing out.”

Three months after the public hearing, I paid Rathbun a visit. He and his wife, Monique “Mosey” Carle, live on Bayshore Court, in a two-story home once owned by a shrimper. I drove past several mailboxes shaped like dolphins and fishing tackle, then past four yard signs that read “No Squirrel Busters Productions Persons Allowed!” Rathbun, in sun-bleached cargo shorts and a backward ball cap, greeted me at the door. In his living room, two laptops were running. A bookcase bulged with Scientology manuals and plastic-wrapped first editions of Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health, the canonical text published in 1950 by Hubbard. “I love Scientology,” explained Rathbun, who considers the religion a practice of “doingness.” “But there needs to be a differentiation between the Church of Scientology and the philosophy.”

One of the religion’s beliefs is that people are “thetans,” immortal beings who have lived many lifetimes. Through coursework and intense one-on-one counseling, known as auditing, a person can transcend any trauma from these past lifetimes to achieve a “clear” state. Over the years, Rathbun said, he audited such notable names as Cruise, Travolta, and Kirstie Alley. But in early 2000 he began to have misgivings; he claimed that he had witnessed the mistreatment of followers and that they were being charged in the thousands of dollars for audits. (The church says Rathbun’s statements are false.) In December 2004 he left his staff apartment in Clearwater, Florida, and headed for the Texas Gulf Coast, where, he said, “I knew a man in his forties could find work without too many questions.” He landed odd jobs, like selling beer at Corpus Christi Hooks baseball games. When he later applied for a paralegal position in Houston, he learned during the interview that he was listed on Wikipedia as dead.

“I felt like an alien,” he told me, “cut off from the only life and friends I’d known.” His job as inspector general, he said, had involved, among other things, “intelligence, reconnaissance, infiltration, and litigation,” especially concerning those who criticized the church, and he knew he’d attract notice if he spoke out. In 2006 he moved to Ingleside on the Bay with Carle, whom he’d met on Match.com. By then he was writing for community newspapers such as the Coastal Bend Herald, and word of his whereabouts spread among other ex- Scientologists, who eventually began knocking on his door. Using an E-meter, a polygraph-like device, Rathbun offered auditing sessions, allowing visitors to crash on his guest bed and accepting donations in return.

On April 18, 2011, Rathbun told me, he was making a sandwich when he heard footsteps outside his glass kitchen door. He turned to find three men with cameras strapped to their heads. They wanted the E-meter. (That Rathbun audits independently—and that he audits his wife—seems to have particularly angered SBP.) He refused, and the visits progressed from on-camera demands for auditing files to as many as 21 drive-bys a day. Some days, Rathbun said, a Squirrel Buster posing as an ex-Scientologist in need of help would show up, asking too many questions about money. Other days, when Rathbun and Carle went for burgers at Nightlinger’s, they’d notice a table of Squirrel Busters nearby, cellphones pointed in their direction. Or, he continued, he and Carle would step out to smoke Marlboro menthols on their back deck, which overlooks a canal, only to be greeted by a Squirrel Buster in a paddleboat. At one point, Carle was sent an unmarked package containing a dildo at her office. In September, on the same day as the Squirrel Busters’ report on his presumed “sex toys,” Rathbun was arrested on misdemeanor assault charges for snatching the sunglasses off the face of a cameraman.

The three weeks since then had felt unusually quiet. “Since the day of the arrest, they’ve been hiding,” Rathbun said. The hiatus had been strange for his household, which includes Chiquita, a Chihuahua mix, and a cat named Tinkerbell. As we talked, Carle joined us, and I noticed that she, Rathbun, and Tinkerbell couldn’t help glancing every few minutes through the window’s blinds. Finally, he pulled the blinds open. He pointed to a home 150 yards away. “The Squirrel Busters are still renting that house there,” he told me.

Within minutes, a black sedan had turned onto Bayshore Court. “They know you’re here,” Rathbun said. He grabbed a video camera. Carle pulled a leatherbound notebook out from under the coffee table. Chiquita trotted to the window, ears perked. We watched as the sedan’s driver snapped a photo of my rental car. “They sent him over here to run your plates,” Rathbun told me.

Carle scribbled an entry in the notebook. Most mornings, Rathbun said, she updated their log while he uploaded videos of himself surveilling the surveillance. (At the Squirrel Busters’ last appearance, Rathbun had stepped out to film them. “You are literally out of your minds,” he said. “You people are sick.” He then uploaded the footage to his YouTube channel.) On the blog, the couple posted photos of new Squirrel Busters they met, requesting help in identifying them.

That afternoon, I called on the Squirrel Busters. A harp-playing angel, surrounded by four video cameras, adorned the door of their house. Though I could hear people inside, and a car and a golf cart sat in the driveway, no one answered my knocks. At sunset, I met up with Rathbun and Carle as they took a walk along the water’s edge. We passed the Squirrel Busters’ house, and the upstairs lights suddenly went dark. I told the couple about my visit and how no one had come to the door. “They were there,” Rathbun replied. “They’re probably emailing your photo around tonight. What car was there? We’ll run the plates.”

Sometimes, he told me, when he and Carle needed a night away, they’d sneak across Harbor Bridge to a bar or restaurant in Corpus Christi. But they always left their cellphones at home and took disposable ones instead. I asked if he thought the Squirrel Busters could track him through his phone. “Think? I know they can get into T-Mobile, absolutely.” On their outings, the couple would park on the lowest level of an underground garage. Later, if they splurged on a hotel room, they paid only in cash. “They are wired into the finance companies,” Rathbun said. No credit cards.

I asked whether anyone had told him that he sounded a little paranoid. “Who says I’m paranoid?” he snapped. We cut through the grounds of the Ingleside Beach Club, passing by the Squirrel Busters’ house again, which was still dark. Then we noticed a red blinking light floating on the second-story porch. “Smile,” Rathbun said. Carle giggled. “See, I told you,” she whispered. “I told you they were going to put on their night-vision goggles.”

A few days later, I reached an assistant producer for SBP over the phone, a Corpus Christi resident named Ralph Gomez. “Marty instigated a lot of this,” he told me. “He has not been practicing Scientology the way he should. The documentary is about his rise and fall, because he views himself as a guru. He is not Mr. Scientology.”

Later, my phone rang. It was Richard Rogers III, a Corpus Christi lawyer retained by the Squirrel Busters. He informed me that the documentary was still in production and read a statement from SBP declaring that the crew had “at all times acted properly and fairly.” It was they who had become “the victims of violence and property damage by Rathbun,” a fact that the documentary would make clear.

When I spoke with Rathbun again, in early November, he reported that the Squirrel Busters had moved out. He was preparing to speak to Inside Edition, and he had been contacted by the St. Petersburg Times for a second series on the Church of Scientology. “I told them to follow the money,” he said. The battle in Ingleside on the Bay was over for now, but not the war. Rathbun was staying. If and when the Squirrel Busters returned, he vowed, he would fight to protect his neighbors.

At the end of my visit, I had accompanied Rathbun and Carle on a boat ride. After riding a few waves, Rathbun cut the engine. “Sunlight is the best disinfectant,” he said. Then he looked over his shoulder at the town. “This is the first home I’ve ever really had,” he told me. “I got into the church looking for a family and thought I had one. But this place is the ideal I’ve been envisioning my whole life.

“It’s funny,” he continued. “We didn’t really interact with the town until this started. Now we actually have friends because of it.”