I grew up in a grocery store in Amarillo. My dad and his brother took over Central Grocery, the family business, from their father when they returned from World War II. In 1962, when I was ten years old, I started going to work with Dad on Saturdays. I carried around a milk crate to stand on so I could work produce or bag groceries, my apron rolled up so I wouldn’t trip on it. The store was a marvelous place for a little kid, but the best part, the heart of it, was the meat market. Central Grocery was known around town for its fine meats, and the star of the operation was the butcher. The butcher was special: He didn’t sack groceries, run the register, trim the lettuce, or stock the shelves. The meat market was off-limits to me—its floors were slick, the knives were sharp, and the butcher was not to be disturbed.

One butcher stands out in my memory. I was in my early teens when he came to us. His name was Harold Hines, and everyone said he was a really good butcher; I can’t say if that was true or not, but I do know he was friendlier with the customers and with me than most of his predecessors had been. What really set him apart, though, was that once or twice a month, on a Saturday, Harold would make barbecue. That’s what he called it, although it was something he prepared in a big electric slow cooker in the meat market. I loved it—the smell that filled the store, the little cardboard bowls he’d give me to sample from, the soda crackers and longhorn cheese. The aroma drew folks to the market. Harold was a star.

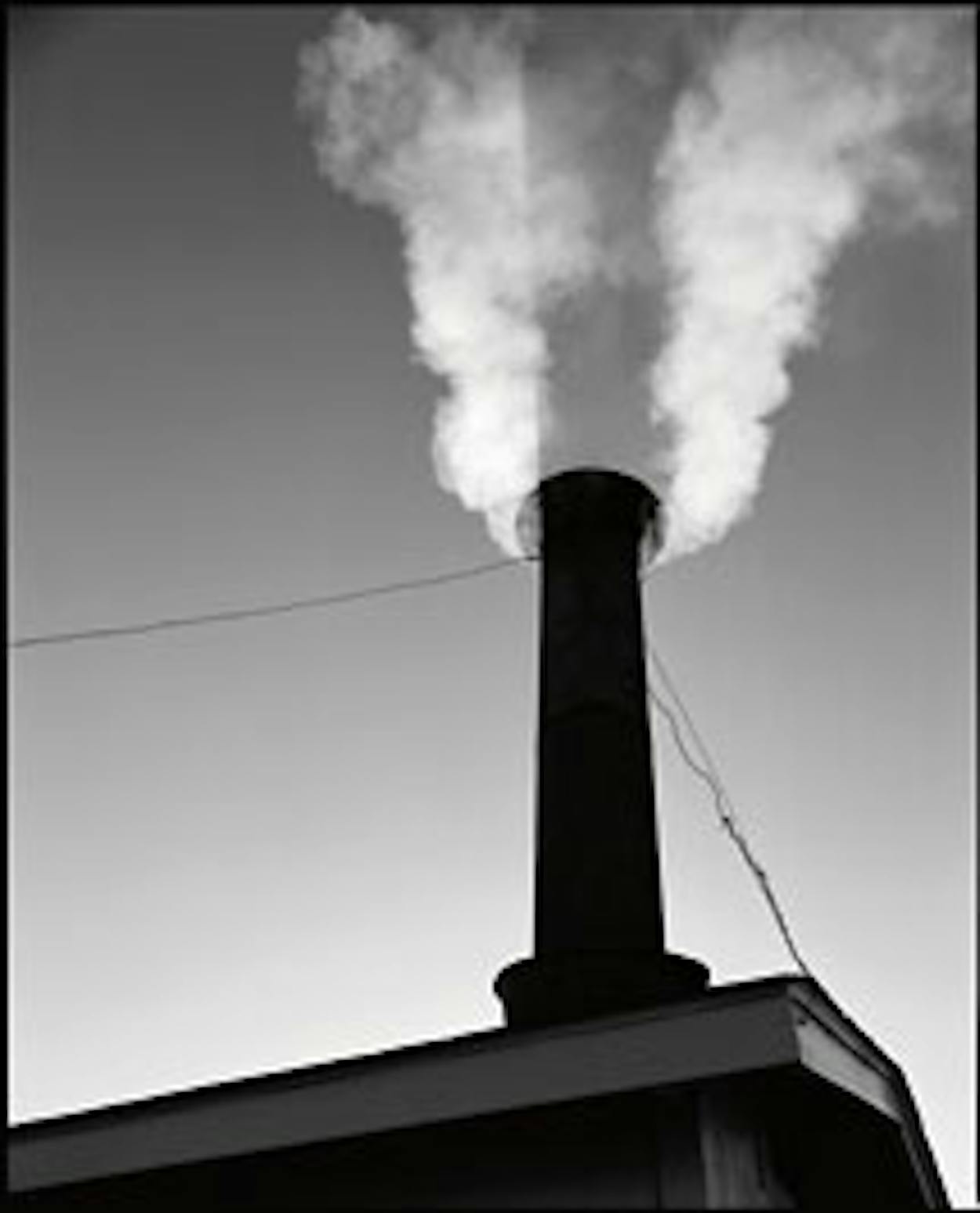

For the past fifteen years, as I’ve traveled around Texas looking for barbecue places to photograph, my inner sack boy has been reawakened. Some of the places I visited weren’t so different from Dad’s store: Prause Meat Market, in La Grange, with the beautiful Friedrich refrigerated cases made in 1952, the year I was born; Gonzales Food Market, where co-owner Rene Lopez Garza still wears an apron and paper hat from a bread company; Dozier’s Grocery, in Fulshear, with a modest display of canned goods and paper products standing between the entrance and one of the most eye-popping selections of meats I’ve ever seen. What these places have that Central Grocery didn’t is real wood-smoked barbecue, made out back in brick pits fueled by post oak, pecan, and mesquite.

Many of the places I visited started out as meat markets. Kreuz Market, in Lockhart, and City Market, in Luling, still display vestiges of their butcher-shop heritage, even though these days the house specialty is smoked meats. Over time the process of creating pit barbecue has transformed such modest spots into magical places. The smoke and heat have penetrated the walls and the people who toil within them. Part of the magic is in the food; part is the fact that I was always made to feel welcome. Whether I called in advance or dropped in unannounced, I was, without exception, free to shoot whatever interested me. These pictures are my thank-you to all the wonderful folks, all the Harolds, who let me inside their lives and who took the time to stand for me or open a pit or stoke up a flame.