This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

In the dead of the night, after everyone else in the house had gone to bed, he would pull out a small notebook that he kept hidden away in a table drawer. It was a journal he had started keeping, no more than fifteen pages, each page containing a sentence or two.

“I was harassed because I wasn’t someone else,” he wrote on one page, and then he stopped. “I stayed civilized under primitive conditions,” he wrote on another page, then stopped again.

He sat for hours, the only sound in the house coming from the ticking of a clock. Outside, his dog pressed his nose against the patio door, hoping to be let in. Finally, he began to write on a third page, pressing down so hard that his pen almost ripped through the paper.

“I have to be able to express my hurt—my pain—my animosity toward you or I will die . . .”

The football arched through the air, traveling in a tight spiral, and the 2,500 fans of the Richland High School Rebels rose from their seats with a startled roar. It was 1995, an autumn evening in suburban Fort Worth, and the quarterback for the Haltom Buffalos, Richland’s longtime rivals, had flung a pass toward an open receiver halfway down the field. But Richland’s free safety, senior Lance Butterfield, was already racing for the ball, his head held straight up, moving so smoothly that his shoulder pads hardly rattled. At the last second, just when the football seemed beyond him, he leapt, stretching his body and pulling the ball away from the baffled Haltom wide receiver, who had no idea that Lance was even nearby.

“Butter! Butter! Butter!” students and parents chanted from the stands. To them, Lance Butterfield was the kind of old-fashioned hero rarely seen anymore in high school sports. Lean and handsome, with an earnest face and a gentle smile—“A smile that could melt a room,” his English teacher used to say—he maintained a 4.0 grade point average and was a member of the National Honor Society and Young Life, a Christian student fellowship organization. He didn’t get in fights, he didn’t skip classes, he didn’t drink or smoke, and he was unfailingly polite, even taking the time in the locker room to talk to hapless third-stringers who rarely got a chance to play. “In so many ways, he glowed with promise,” says Richland’s head football coach, Bob Briscoe. “Lance was the all-American kid, and everyone perceived him that way.”

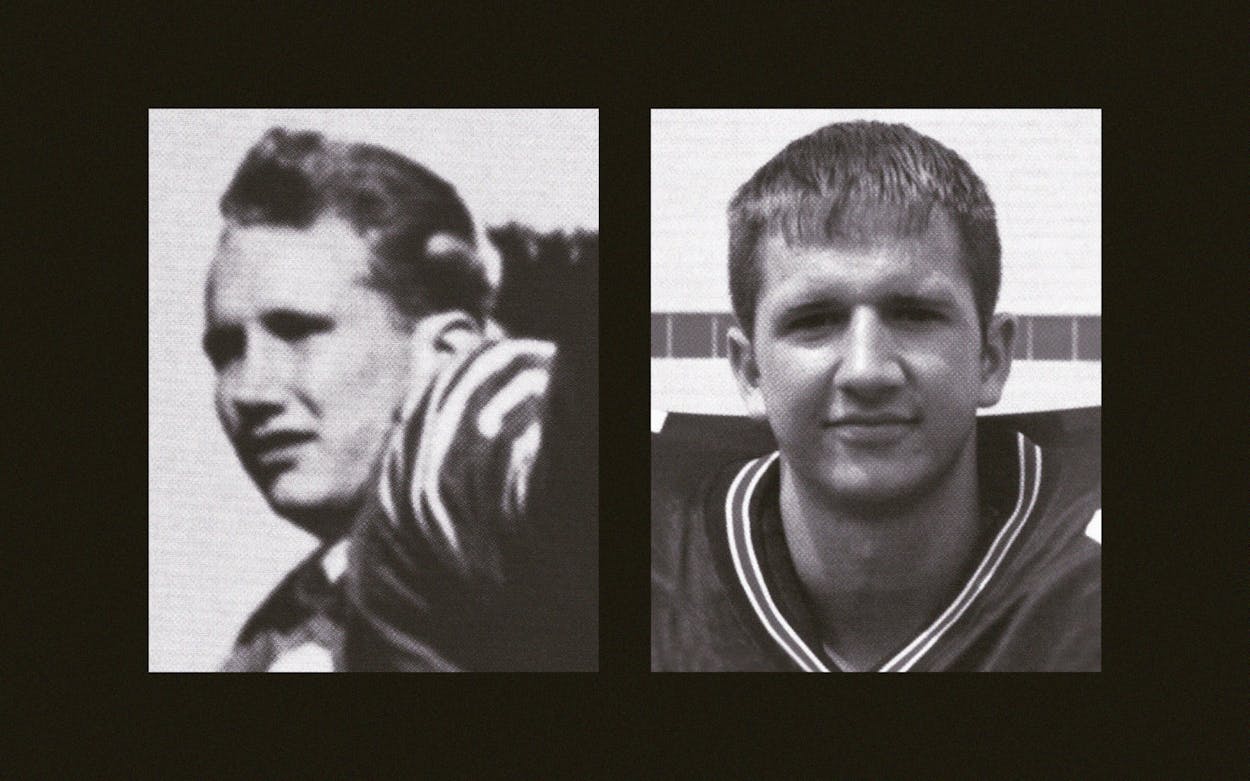

At every game, sitting on the top row of the bleachers, was Lance’s always-smiling mother, Kathy, who taped the games with a small video recorder, and Lance’s father, Bill, a former high school football hero himself who, almost thirty years after his own playing days, still carried himself like an athlete, his chest thrust forward and the muscles in his upper arms like knots. It was amazing, the fans used to say, the way Bill Butterfield’s blue eyes remained fixed on his son during the games. He studied Lance like a scientist, missing nothing. Many in the stands knew that during Bill’s own days as a running back at Amon Carter Riverside High School in Fort Worth, he was considered the ideal all-around athlete, the kind of player colleges craved. Not only was he strong—coaches fondly called him Butt because of the way he would lower his head and head-butt anyone who tried to tackle him—but his speed was astonishing, especially on the sweeps, when he would feint toward the line with a shake of his head and burst outside without breaking stride.

And now here he was passing on what he knew to his son. Butt and Butter, the fans said, were the perfect father-son team. Bill was so devoted to his son that he left work every afternoon just to watch Lance’s practices. He devised extra workouts for Lance at home, he gave him protein drinks twice a day, and he installed $10,000 worth of weight-lifting equipment in the garage. Under his father’s guidance, Lance was both the most superbly conditioned athlete on the field and the smartest player, someone who understood the game almost as well as the coaches.

“Your boy was great tonight,” the other parents would tell the elder Butterfield. Bill would smile—a thin, wise smile—and he’d say, “Oh, he’ll be better next week. He’ll be better.” Then he would head home to watch the videotape of the game his wife had just filmed.

In the winter months following that championship season, when curious outsiders would ask what went wrong, the Richland fans would shake their heads. Nothing felt out of place, they insisted—it was a perfect time. The team was playing so well together and was on its way to a district title, the first in a decade. And, the fans said, it was such a delight to watch Lance, who at the end of every game stayed on the field as if he never wanted to leave. He seemed to be drinking in those nights, those glorious autumn nights when the Rebels were winning and everyone was cheering and all of a young man’s dreams seemed capable of coming true.

Sometimes the entries were only fragments of sentences. “I still me I haven’t changed,” he wrote on one page, then stopped. “Spent life-perfect you.”

He seemed to be searching for just the right words. “You don’t understand what I mean by spending life competing against the world with my actions,” he wrote. And then he stopped again.

Every December in various neighborhoods in North Richland Hills, one of the many bedroom communities near Fort Worth, the residents cover their hedges and porches with Christmas lights. They lug Santa sleighs and snowmen to their roofs, and they are considerate enough to park their cars in the garages at night so the hundreds of families from other suburbs who drive in to see the displays won’t have their views obstructed. In the mid-nineties many of those families drove past a particularly cheerful home with blinking lights around the borders of the front yard, a plywood painting of Mr. and Mrs. Claus next to the sidewalk, and another large sign in the yard that read “Merry Christmas From the Butterfields.”

Bill and Kathy Butterfield owned a small mattress manufacturing company, and they had three children—Billy, born in 1968, his sister Sandy, born three years later, and young Lance, born in 1977. Around the neighborhood, the Butterfield children were famous for their manners. They shook hands with every adult they met, always said “sir” and “ma’am,” and never needed to be reprimanded. “You’d see the whole family at a restaurant, and the children rarely spoke unless an adult spoke to them first,” recalls Wade Parkey, a congenial North Richland Hills insurance agent who grew up with Bill and Kathy near downtown Fort Worth. “What also impressed you about Kathy was that she was so incredibly polite, with this light, sweet voice. It was almost as if she thought she might offend you by talking too loud.”

Bill Butterfield looked the part of a former football star. He dressed mostly in sweats, he owned at least a dozen pairs of the same expensive Nike cross-training shoes, and he worked out daily, running up and down the bleachers at the high school practice field. He made regular trips to the GNC vitamin store at the mall to check out the newest supplements, and he read constantly about nutritional theories and training techniques—the trainer for the high school athletic program jokingly called him Dr. Butterfield.

But no one doubted his knowledge of sports. “He’d talk to you about your kids and how they were doing,” Parkey says, “and he could point out flaws in their baseball swings or the way they tackled. And he was happy to talk to the kids when they needed extra motivation.” He didn’t hesitate to tell other parents that sports was the best way to instill discipline and drive in a child’s life. In fact, even though Bill was the president of the mattress company, it was Kathy who went to work each morning to run the business—Bill spent most of his time training his children. When Billy was in the second grade, Bill set up daily workouts for him, having him do pull-ups from the top bar of the swing set and then run wind sprints in the yard. He later taught Billy to be a switch-hitter, and he took him to a park and pitched batting practice to him for hours while Kathy, Sandy, and Lance, who was then just a toddler, shagged balls in the outfield. Bill had Sandy playing softball and basketball, and he told her that if she wanted to be a cheerleader, as her mother had been, she would need to develop a better body, which meant eating less. He kept her away from all sweets and carbonated drinks, and he went so far as to order for her when they went to restaurants.

Some parents, of course, were disturbed by Bill’s obsession with his children. During Billy’s baseball games, Bill sat in the stands until Billy came to bat. Then he walked to the backstop to critique his swing. Once, during a critical inning, when the coach of Billy’s baseball team ordered him to bat right-handed, his natural way, an outraged Bill stormed onto the field and shouted at the coach, “What the hell do you think you’re doing? My boy is a switch-hitter!” At a youth-league football game one night, Bill ran out onto the field after a referee made a poor call against Billy, grabbed the ball from the referee’s hands, threw it into the darkness, and stomped off the field.

There was no question that Bill often let his competitive spirit get the best of him. Bill’s neighbors had also heard stories about his disciplinarian methods. According to one rumor, Bill had grounded Billy for a week for not playing well in a youth-league football game. One of Sandy’s girlfriends said that several times when she went over to the Butterfield house, an angry Bill met her at the door and demanded that she open her purse so he could make sure she was not sneaking in food for Sandy. Some parents had heard Wade Parkey tell the story about the evening in 1984 when he and his wife, Arvettia, invited Bill and Kathy over for a night of cards. After the Butterfields lost the first hand, Bill threw his cards at his wife and yelled, “You are a stupid f—ing bitch!” Parkey was shocked, at a loss for words. But Kathy quickly smiled, said, “Oh, I’m sorry,” and after a few minutes, the couple acted as if nothing had happened.

For all of his tantrums, however, Bill was liked well enough around the community that he was voted president of Richland High School’s booster club after Billy started school there. Parents flocked to the booster club meetings to hear Bill talk football—he could explain Richland’s veer offense to them as well as the coaches could. Even the high school coaches liked him. “To be honest with you, we didn’t see him as being that different than any other sports-oriented dad,” says Coach Briscoe. “And there was a lot to admire about him. He was a good teacher, especially the way he had trained Lance. You could tell that Lance was going to make something of himself.”

“Definition of insanity,” he wrote on another page. “Doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.”

Although never a star, Billy Butterfield did become a starter on Richland High School’s baseball and football teams, and Sandy did become a Richland High cheerleader. After they graduated, they left North Richland Hills, Billy for a junior college in Colorado and Sandy for Texas Tech University in Lubbock. By the time Lance started junior high school in 1989, he was the only child left.

Kathy used to call her youngest son “the gentle child.” Whenever Lance saw a cricket in the house, he’d catch it and set it free outside. He kept to himself, going straight to his room after school to study. Although Lance, like his brother, began a running and pull-up regimen once he reached the second grade, the truth was that Bill didn’t give him much attention during his early years, focusing mainly on Billy. Other parents noticed that the father would take his sons to the park and leave Lance alone for hours at a playground while he and Billy went off to another field to train.

But one afternoon, an assistant coach from Texas Christian University walked into a sandwich shop where the Butterfields were eating. He recognized the twelve-year-old Lance—under his father’s orders, Lance had attended TCU’s football clinic earlier that summer—and turned to Bill and said, “If your boy keeps his head on straight, he’s going to have a great future.”

Bill gave Lance a long, curious look—he seemed to be seeing his son for the first time. “And right at that point,” recalls Wade Parkey, “everything changed. I remember Bill saying to me, ‘Wade, Lance is my last chance. He can make it.’ I could see Bill’s whole demeanor changing. He was going to make his son a star.”

Bill had Lance jump rope daily in the driveway to improve his quickness, run up and down a hill near the house for endurance, and lift weights in the newly converted garage. He put Lance through rigorous football drills in the yard, making him backpedal furiously as if he were covering a wide receiver and then leap into the air as if to intercept a pass. Determined to make Lance a star in baseball too, Bill built a gigantic backyard batting cage, the size of batting cages at public parks, and he bought an electronic pitching machine. He installed floodlights in the yard so that he and Lance could practice into the night.

At Bill’s instruction, Kathy made a steak and baked potato every night for Lance, and she was also in charge of taping all of his games. Afterward, Bill would go through the tape with Lance, pointing out his mistakes, rewinding the tape over and over to the same spot until Lance understood what he had done wrong. Lance studied the tapes intently, never moving from his seat. When his friends asked him to spend the night, Lance would tell them he was sorry, but his father wanted him to get up at six every morning for a five-mile run. When one friend invited him to his family’s lake house for the weekend, Lance said he couldn’t go because his father wouldn’t want him to miss two days of workouts. “I know that some of the boys would ask him, ‘Lance, why do you always do what your father wants?’ ” says Sharon Kates, a neighbor whose son Matt was the same age as Lance. “And his reply always was, ‘Because I respect him. He’s my father.’ ”

And as far as anyone could tell, Lance was willing to do anything for him. Late one afternoon, Wade Parkey pulled up to the Butterfield’s home and heard the sound of the pitching machine in the back yard. As he walked around the house, he heard Bill shouting.

“Watch the f—ing ball, Lance! . . . What is wrong with you? . . . Maybe this will teach you to keep your eyes on the ball!”

Parkey came around the corner and saw Lance cowering at the plate. Bill had aimed the pitching machine directly at his son, and the balls were spitting out at 60 miles per hour, bouncing off Lance’s body.

“Bill!” Parkey shouted. “What are you doing?”

Bill looked surprised. But he recovered quickly and said, “What the hell does it look like we’re doing, Wade? This is a concentration drill.”

Parkey stared at Lance, whose eyes were indecipherable. Then he saw that, from inside the house, Kathy was watching them through the family-room window, her hand frozen to her mouth. For a moment, he thought she was going to rush outside. But Bill’s eyes also turned to the window—and Kathy slowly backed away.

Lance broke the silence. “I’m sorry, Dad. I’ll do it right this time.” Then he resumed his batting stance, waiting for another ball to come flying out of the machine.

On one page was the same sentence repeated thirteen times. “I wasn’t somebody else. I wasn’t somebody else. I wasn’t somebody else. . . . ”

In Fort Worth in the mid-sixties, nobody trained like Bill Butterfield. All summer long, wearing ankle weights, he ran six miles a day up and down the steep Trinity River levees, and then he went home and lifted barbells. During the ferocious two-a-day practices in August, he went the entire day without taking a drink of water—to make himself tougher. “He was a natural-born leader, an inspiration to the rest of us,” says former Amon Carter teammate Richard Sloan. With his wavy hair and a lopsided smile, Bill looked a little like James Dean. He tooled around the neighborhood in a ’55 Chevy, and he played the guitar and sang at the school talent shows.

Kathy Adams, the daughter of strict Baptists and one of the prettiest girls at school, told her friends that she didn’t like the way Butt cussed and that she was bothered by his temper. Still, like a lot of other girls, she sat by the phone every night, waiting for him to call. When they started dating, they were considered the ideal couple, voted favorites of their sophomore class. Then, in the summer of 1967, just before their senior year, word spread that Bill and Kathy were going to be married at a brief courthouse ceremony. Kathy was pregnant. In one passion-filled teenage night, she and Bill had had sex on the fifty-yard line of Amon Carter’s football field.

The news stunned the whole school—the whole city, even. Under the headline WEDDING BELLS CRIPPLE WINGS OF THE EAGLES, the Fort Worth Press reported that Bill Butterfield would no longer be playing for Amon Carter; the school had a rule against married students playing varsity sports. Just like that, the great Butt’s career was over. He and Kathy moved to a tiny duplex to start their new life.

He continued to keep himself in top physical condition, running up and down the bleachers at a high school stadium. “You know Bill had to be deeply disappointed about leaving Carter and losing a chance at a scholarship,” says Bill Crawford, a former teammate. “But he had a way of keeping things hidden.” Telling none of his friends, he attended an open tryout for the Dallas Cowboys in the early seventies; he put weights in his shoes so he would be heavier on the scales at the weigh-in. Bill was cut after the first round. When Kathy tried to give him a hug when he came home, Bill suddenly reached back with his fist closed, two knuckles sticking out, and popped her so hard in the chest that she thought one of her breasts was going to cave in. “You keep away from me, you f—ing bitch!” he shouted. “You keep away!”

At the time, she later said, she assumed that he was just frustrated. But his anger kept building, especially around the children. “He told me that his children were going to grow up right,” Kathy recalls. “And he said that you raise a child like you raise a dog. You beat them until they obey.” He would slap their hands if they touched a glass vase on the coffee table or if they accidentally spilled their food at a meal. When they got older, he began using a solid oak paddle, three and a half feet long and three quarters of an inch thick. Kathy lost count of the times she watched him coming down the hall, slapping the paddle into his palm, his shadow bobbing along the walls. He would tell the kids to put their hands on the edge of their bed and bend over. They learned to take their licks without making a sound. If they ever cried out, their father would only hit them harder. Sometimes he would hand the paddle to Kathy. “Your turn,” he would say, his voice stabbing into her ear. Trembling, she would try to get away with a halfhearted swipe, but Bill would grab her hair or kick her in the back. “Harder, you bitch! You’re the one who taught these kids to disobey!”

Kathy was not strong. She was not a fighter. Only one time, a few years into their marriage, had she tried to leave, carrying young Billy and Sandy to the car and racing to her parent’s home. But Bill followed them, nearly knocking the door down to get to her, pushing her elderly father against the wall and telling him to stay out of his business. Kathy realized that if she ever tried to hide from Bill again—if she and the children went into one of those underground programs she had read about in Good Housekeeping—he would abandon the home, the mattress plant, everything he owned, just to find them. She decided she had no choice but to return home and, for the children’s sake, try to make everything feel as normal as possible. She bought sports posters to cover up the dents in the doors Bill had kicked in. She cooked large meals and smiled lovingly at all times. When Richard Sloan drove past their home one afternoon and saw her in the driveway in a rubber sweat suit, with one end of a rope tied around her waist and the other end tied to the back of a car, she put on her best smile and waved cheerfully and called out, “Bill is just helping me lose weight.” Shrugging at Sloan as if the whole scheme were Kathy’s idea, Bill began pulling Kathy around the block, forcing her to run at full speed. Her breaths came in little whoops. But Kathy kept smiling.

“He pretty much controlled everything that went on in the house—everything we ate, everything we did,” Sandy said later. “It was like walking around on eggshells. We just tried real hard not to do anything wrong.” Lance became an expert at acting like the model child, going to school every day wearing crisp, button-up shirts, neatly tucked in. Even his jeans were ironed. “Our parents would hear us tell stories about Lance spending two hours working on a single calculus problem, and they’d ask us why we couldn’t be more like him,” says one of Lance’s friends and football teammates, Jason Meng. Besides his straight A’s, he was such a perfectionist in sports that “when he made the smallest mistake, he would hang his head in embarrassment,” says Coach Briscoe. “We didn’t have to get on him because he was already so hard on himself.”

“You don’t understand the straw that broke the camel’s back, but there is one. . . . When it happened to me—you didn’t understand you still don’t.”

During the first football practices of Lance’s senior year, a pretty girl began jogging around the track that circled the practice field. Kim Maywald was a clear-complexioned, brunette junior with a perky personality and a way of giving boys long, lingering looks. And when Kim loped around that track, she aimed those looks at Lance.

In the past, plenty of girls had slipped Lance romantic notes, but he kept his distance. Although he had never been told the reason his father’s football career ended—Bill didn’t want any of the children to learn the story of Kathy’s teenage pregnancy—he had been warned many times by his father to limit his extracurricular activities to sports. “You don’t want those girls turning you into their pacifier,” a disgusted Bill often said.

But Lance and Kim found themselves in the same computer class that fall semester. He started walking her down the hall, and soon he was holding her hand while she dug the point of her chin into the muscle of his shoulder. For Lance, the experience of a first girlfriend must have been overwhelming. He bought Kim stuffed animals. He wrote her lavish love notes, which she kept in a shopping bag under her bed. In them he called her “my little cowgirl” and “my snugglebunny” and always concluded with the phrase: “With all my love from the bottom of my heart to the top of the sky . . . Butter.”

To keep the relationship a secret from his father, Lance met Kim at Young Life meetings, and afterward they slipped away in his new pickup, parking on a remote street next to a golf course. But Bill already knew something was going on. From his position at the top of the bleachers during Richland’s practices, he had seen the looks that passed between Kim and Lance. He began getting in his pickup and tailing Lance whenever he left home at night. He also began staking out Kim’s house, even following her to and from school, sometimes making Kathy come along with him. “He became obsessed with Lance and this girl,” says Kathy. “I remember him saying, ‘That little bitch Kim is going to ruin everything for us!’ And I thought, ‘What does he mean by us?’ ”

Bill had planned carefully for Lance’s senior year. To make his son more muscular, Bill was giving him ten to fifteen pills every morning—vitamins, liver pills, protein supplements, and metabolic boosters. At the end of each school day, he was at the locker room with a protein drink for Lance. Then, in the third game of Richland’s season, Lance mistimed an interception attempt that led to a touchdown for the other team. A few days later, a devastated Bill Butterfield appeared at Coach Briscoe’s office and confessed, “I think his mind is on other things.”

“Bill, it was just one pass,” replied a perplexed Briscoe. “Lance will be fine.”

“Coach, I’ll get him back on track for you.”

Bill ordered Lance to drive over to Kim’s house and break up on the night of her seventeenth birthday. When Lance asked if he could wait for another night, Bill grabbed him by the shirt and snarled, “Don’t you ever f—ing talk back to me again.” Lance arrived at Kim’s birthday party and asked her to step outside. With tears in his eyes, he told her it was over. He said his father had told him he wasn’t even supposed to look her way during computer class. “I said, ‘Lance, you are eighteen years old. Your father can’t control your life forever,’ ” Kim recalls. “And he said, ‘I know, I know. But you don’t know what my dad can be like.’ ”

Lance did get back on track in football. After his two interceptions against the Haltom Buffalos in October, he was named one of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram’s players of the week. Richland fans proudly shook Bill’s hand, but he was not satisfied. “Lance could have had three,” Bill snapped to one father. Bill told Parkey that Lance needed to be tougher for the upcoming playoffs. “I need to get the pussy out of that boy,” he said.

Like other parents, Parkey used to chuckle at what he called Bill’s “eccentricities”—to lose weight, Bill once went for weeks eating only Rice Krispies—but now Parkey was becoming genuinely alarmed. He knew that before each game, Bill would take a Vicodin, a powerful prescription painkiller, and sometimes he’d take another at halftime. Yet at one game the relaxant had little effect. Wearing a camouflage hunter’s suit to keep warm, Bill rose and screamed at the coaches, “You f—ing idiots! Turn the page on your playbooks!” The whole side of the stadium turned to stare at him. Her hands shaking, Kathy kept filming with her video camera, too embarrassed to pull it away from her face.

Lance and Kim tried to keep their relationship alive, meeting in the back hallways at school or in darkened movie theaters. But Bill was determined to keep them apart. At a party for one of the football players, Bill was spotted half a block away, sitting motionlessly in his truck, staring at the player’s house, the exhaust from the truck’s engine muttering softly against the pavement. Lance, his head lowered in shame, told his teammates that his father was still following him. After Kim’s parents learned that Bill had not stopped stalking their daughter, they complained to the North Richland Hills Police Department. To avoid further detection, Bill rented a car to follow Lance and Kim. One evening Lance and Matt Kates were driving around when Bill passed them, made a screeching U-turn, and came right up on their back bumper. “It’s your father!” Matt cried. “He’s going to run us off the road!” Bill, however, seemed content just knowing that his son had seen him. He followed them to a friend’s house and waited outside for several minutes before driving off.

Soon, alarms were going off all over the neighborhood. In late October word spread among the other players that Lance had shown up at the home of his friend Carl Prichard, asking if he could stay the night. When Kathy called looking for him, Carl’s mother could hear Bill in the background cursing and throwing things against the wall. Although the Prichards told Lance that he could stay with them as long as he wished, he returned home, saying his dad was just “a little high-strung.” But on a freezing night a few weeks later, dressed only in a pair of sweat pants, Lance pounded on a back window of Matt Kates’s house. He was shaking uncontrollably. Matt wrapped him in a bed cover, then held him. “My dad tried to strangle me,” Lance gasped. “He caught me on the phone with Kim, and he jumped on me and put his hands around my neck, and he started choking me.” Once again, Kathy tracked Lance down and told him that Bill had promised not to bother him as long as he came home. Lance was hesitant. Then Kathy pleaded, “Please come home.” Lance knew the meaning of her words. If he didn’t go, Bill was likely to explode and hurt her. Mrs. Kates heard Lance say over the phone, “Mom, I’ll come home for you.”

Lance’s teenage love affair had clearly loosed something in Bill Butterfield’s head. One night in November, when Wade and Arvettia Parkey were having dinner with Bill and Kathy, Bill suggested that they drive back to their old Fort Worth neighborhood. They piled into the car and cruised past the small, unlit homes where they grew up. Bill told Parkey to stop at the Amon Carter High practice field. While Kathy and Arvettia walked toward the end zone, Bill and Wade stood on the fifty-yard line. Under the dim glow of the moon, Bill looked into the distance and said, his voice trembling, “This is where it all ended for me, Wade. Right here, it all ended. All because of one night . . . one f—ing night.”

Several nights later, while cleaning the house, Kathy came across a little notebook hidden away in a desk drawer. She had seen her husband in previous weeks writing in it, but he had refused to tell her what he was doing. “This involves or is the past,” she read on one page. “Everything stems from past.” On another page was a short sentence about high school: “Junior Summer: Pain Every Summer Since.” And then, her heart in her throat, she came to the last entry: “I have to be able to express my hurt—my pain—my animosity toward you or I will die or worse hurt my kids more than I already have or us.”

Kathy later said that she felt as if she had walked into a Stephen King novel. Her husband was losing his mind. Still, she tried to convince herself that if the family could get through that last season—if Lance could play well enough to help get the Rebels to the playoffs—perhaps their lives could again be, well, “normal.”

Richland did win the district championship, but the Rebels were beaten in the first round of the playoffs by Grapevine High School, 45–28. It was a surprisingly lopsided loss; Lance did not play well. He seemed distracted throughout the entire game. For a long time afterward, Bill sat alone in the stands, the muscles of his forearm rippling as he squeezed his hand into a fist and relaxed it—back and forth, back and forth. Then he shrugged at Parkey and headed home. The next day he was back in the yard with Lance, putting him through new workouts to get him ready for baseball season.

To the Butterfields’ neighbors, the tension appeared to subside. When they were in the yard, Bill and Lance waved at friends who drove by. At the end of the fall semester, Bill allowed Lance to go on a Young Life ski trip to Colorado. Bill seemed relieved to learn that Kim, weary of the clandestine nature of her romance with Lance, had told him she wanted to date other boys.

What no one outside the family knew was that Bill had started beating his son again. While Bill had never hesitated during Lance’s high school years to pop him in the chest with his knuckles or push him against a wall, he had not paddled Lance since he was a freshman. But in early December he told Lance to go to his room and put on a thin pair of athletic shorts. He pulled out the wooden paddleball rackets he had recently bought at a toy store and wrapped together with duct tape. From another room, Kathy heard Bill bellow, “Your problem, Lance, is you didn’t get the shit beat out of you enough when you were younger.” She heard the whack of the paddle. “You going to be a mama’s boy and cry?” Bill roared at his eighteen-year-old son. “Is that what you’re going to do?”

Kathy was too afraid to intervene. She began preparing for the holidays. With Lance’s help, she got the Christmas decorations laid out in the yard, and she made sure the whole family came to the house on Christmas Day. Sandy was there—she was living temporarily at her parents’ home while she looked for a new apartment—and so was Billy, who was married and living nearby, working with his mother at the mattress factory. Lance sat in a corner of the room, saying little. He politely handed his father a present, a couple of old John Wayne movies; his father handed him one in return, a new shirt that Kathy had bought a few weeks before. Kathy gave Lance a framed photo of him making an interception.

The next day, Lance worked for a few hours at the mattress factory, then he came home and spent the rest of the day in his room, lying in bed. Bill asked him if he was sick, and Lance said no. “Then you need to get a workout in today,” Bill replied. Lance went for a run. The next morning, Bill told Lance that he needed to get in another run. Without a word, Lance went running again.

A few hours later, Kathy received a phone call at work from a hysterical Sandy. “Mom, something’s happened between Lance and Dad!”

Kathy drove home frantically and stumbled out of the car, calling Lance’s name. She felt something giving way inside her, like dominoes falling, one by one. “Is Lance all right?” she screamed as she ran toward the house. “Is Lance all right?”

But it was her husband she found inside, sprawled in the hallway, one bullet in his back and another in his brain. Her son was over at Kim’s, sobbing so uncontrollably he could hardly speak.

Lance initially told the police that he had found his father in the house. Then, when a detective in the interrogation room gently asked him if he would like to say a prayer for Bill, he put his hands to his face. He confessed that he had jogged past Kim Maywald’s house that morning and tried to assure her that “everything was going to be cool with my dad,” but upon returning home, he saw his father getting out of his truck, an angry look on his face. Lance realized that his father had been following him again. “It was going through my mind that I could make the pain quit hurting by killing my dad,” he said in his confession. He got the .38 revolver that Bill kept in a kitchen cabinet. After his father, wearing only a towel, came out of the bathroom, Lance shot him in the back. “I said, ‘I’m sorry, Dad.’ He turned and he said, ‘Call 911,’ and he was holding his chest and that’s when I pointed and fired the second shot.” The second shot hit Bill in the middle of the forehead.

The news of the killing hammered North Richland Hills. Like a chorus from a Greek tragedy, many of the Butterfields’ neighbors lamented why no one had done anything to prevent it. They argued whether Lance had committed an act of madness or an act of justice. Kids at the high school wrote “We Love You Butter” on the windows of their cars. Bill’s former teammate Richard Sloan told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram that the only thing Bill wanted was “the best for his kid.” At the funeral, a couple of the pallbearers squabbled over the truth of the stories about Bill’s abuse.

Kathy, Billy, and Sandy arrived at the Tarrant County District Attorney’s office to ask that the murder charges be dropped, saying they preferred to handle the situation as “a family matter.” But the prosecutors announced that Lance’s trial would send a clear message to teens about the crime of parricide. Lance was eighteen, the prosecutors said, old enough to be accountable for his own life. He was a straight-A student; he knew there were places to turn for help. What’s more, they said, Lance was in no imminent danger that day. Bill was defenseless, coming out of the shower. Just because Lance had a turbulent relationship with his father didn’t give him the right to commit murder in the first degree.

About the only one who didn’t take part in the debate was Lance himself. For days he sat in jail, saying little to anyone. When his mother came to visit, he stared at her through the thick, fingerprint-stained glass that divided them, barely holding on to the telephone that connected them. One psychiatrist who arrived to interview Lance wondered if he was experiencing the kind of post-traumatic stress disorder seen in combat veterans. When Lance met with Randy Price, a well-known forensic psychologist, the boy said, “It’s not like I killed my father. It’s like I don’t have a father anymore.” Price speculated that Lance was subconsciously disassociating himself from the shooting, drifting deeper into denial.

After his release on bail, Lance took correspondence courses in the spring of 1996, earning his high school diploma. He enrolled at a nearby junior college. He called Kim a few times and wrote her letters, but she insisted the relationship was over. When she realized they were taking classes at the same junior college, she transferred to another campus. “Some of his friends believe that if I hadn’t broken up with him back in the fall, he wouldn’t have killed his dad,” Kim said one afternoon, sitting with her mother at the kitchen table. “But I think he was always hoping his dad would die. When he told me on the phone from jail one night how he did it, I hung up and started crying and went downstairs and said to my mom, ‘Mom, Lance is a murderer.’ ”

The trial was postponed for nearly two years. On the first day of testimony last August, the courtroom was overflowing with spectators, most of them Lance’s supporters. Bill’s older sister flew in from California to testify that Lance should be given probation. “Lance has been in prison since the day he was born,” she said. A psychiatrist testified that the Butterfield home was like a concentration camp. Kathy herself testified that Lance was driven to kill his father because “he had no help from me, no help from anyone in the community.”

Lance’s lead defense lawyer, Jeff Kearney of Fort Worth, knew that if the boy was to have a chance at probation, he would have to take the stand and fully explain what he did. But Lance remained reluctant to talk about the years of abuse. Finally, the evening before Lance was to testify, Kearney’s co-counsel, Greg Westfall, asked Lance to write a letter to his dead father, thinking the exercise might help him break through his wall of reserve. Late that night, after everyone in his house was asleep, Lance pulled out some notebook paper and began to write. He wrote a sentence, then stopped. He wrote another sentence, then stopped again. “Dear Dad,” the letter began. “You’ll never know how much I admired you. You’ll never know how much I loved you. Why weren’t you able to love me back?”

When Lance took the stand, he testified so powerfully about his father’s violence that some jurors blinked back tears. But prosecutor Mitch Poe interrogated him for mercilessly shooting his father a second time even after Bill asked his son to call 911. The jury split down the middle—six for probation and six for a prison term. One angry juror demanded a life sentence. After days of deliberations, the foreman passed the judge a note that read “We are close to coming to punches.”

After a mistrial was called, the lawyers on both sides, realizing that the chance of another hung jury was high, got together to negotiate. The district attorney’s office settled for a deal: a guilty plea to manslaughter in exchange for a three-year sentence. Lance’s attorneys declared it a victory. In the courtroom, Lance hugged his mother good-bye, asked a few friends to check on her daily, and was led away in handcuffs.

“Dad, I just wanted our family to be a happy family. Was that too much to ask?”

At the state prison in Beaumont, he stays in shape by doing arm curls with buckets filled with water. He attends church and a Bible-study class, and he is taking college correspondence courses. He keeps his hair neatly combed, his uniform spotless, and he is unfailingly polite around the guards. “They yell and cuss a lot at the new prisoners to see if they can get under our skins,” Lance says with a thin smile. “It’s not a problem for me. I’ve had a lot of experience with yelling.”

He is still having trouble coming to grips with what he did. “When I think about it,” he says, staring blankly at the floor, “I see a part of me leaving my body and walking down the hall and shooting my father. And there’s another part of me saying, ‘Don’t do it. Don’t do it.’ ”

He pauses, trying to maintain his composure, and says he isn’t sleeping well at night because of his dreams. In one of them, he is running like a racehorse across the football field, the crowd urging him on. He leaves his feet at just the right moment, suspended in the air as if flying, and comes down with the ball. He turns to the crowd and sees his mother and older brother and sister applauding. He then sees another man, alone, in the top corner of the stands, his unblinking eyes fixed on Lance. It is the man who turned him into a star—and took away his childhood.

“Dad,” Lance calls out.

But the man never smiles, never waves.

After that dream, when he cannot sleep, Lance gets out his notebook and goes back to work on the letter he started during the trial. He changes it often, he says, trying to get the words right. He recently wrote that he forgives his father and that he hoped his father forgives him. “I still love you, Dad,” he wrote, then stopped.

When he gets out of prison, Lance says, he will go to his father’s grave and read him the letter. He will drop by the football field where the Richland Rebels played their championship season. Then he will go back to his home, the one that was once decorated with so many Christmas lights, and he will go through the front door, calling out his mother’s name to make sure she is safe.

- More About:

- Sports

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- High School Football

- Crime

- Fort Worth