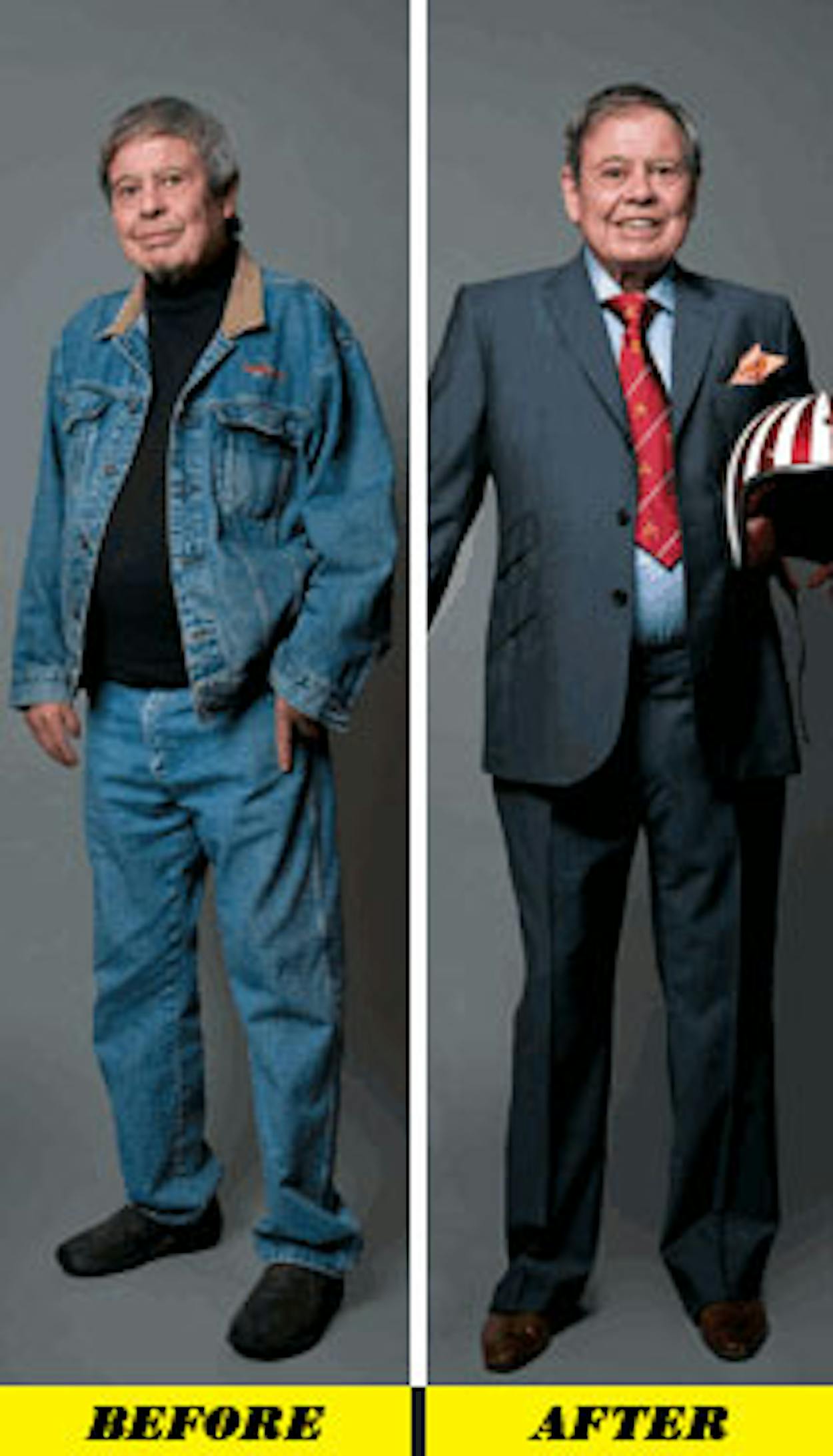

The before and after photos were my idea. I insisted, in fact. They were to be my evidence in case this experiment went terribly awry. Generally I mistrust the concept of makeovers, subscribing to the firm belief that plucking out a pig’s snout hairs and exfoliating his mud-caked backside are no more effective than painting him with lipstick, an exercise in folly much discussed during the last presidential campaign. Nine times out of ten, the pig won’t be able to tell the difference, and neither will anyone else. Personally, having devoted 74 hard years to creating the before, I was reluctant to put myself in the hands of a so-called “makeup artist,” who, with a few dabs of monkey gland oil, might undo my dedicated years of debauchery in her pursuit of some unattainable after. Yet the editors of this magazine insisted. They cajoled and wheedled until I agreed to submit myself to their questionable plan: an extreme and total makeover at the hands of a Dallas stylist. As a condition of the surrender, however, I put them on notice that if the after was substantially inferior to the before, they could expect to hear from my attorney.

As I flew to Dallas on a foggy morning a week before Christmas to meet my makeoverers, I made a mental inventory of my scars and blemishes. The Frankenstein-quality scar that zigzags down the length of my breastplate, as well as the smaller, jagged scar on the inside of my left knee, commemorates an event in 1988 in which a surgeon sawed open my chest, removed a damaged heart artery, and replaced it with a vein extracted from my leg. The cell-phone-size bulge that swells above my left breast is a pacemaker-defibrillator. There are other deformities and irregularities that have become a part of my native character, including ten clawlike toenails and a 38-inch waist that testifies to too many pints of ale and plump pigeon pies. Yet what others might view as flaws I prefer to think of as badges of authenticity, memorials to the nobility of self-abuse, as it were.

The stylist met me at Love Field. She was a slender blonde with a pixie haircut. I could tell from the way she sized me up that I represented an entirely new and possibly insurmountable sort of professional challenge. “I don’t suppose you spend a lot of time in salons and spas,” she asked. I shook my head. “No, I didn’t think so.”

Our first stop was a hair salon inside the Neiman Marcus at NorthPark Center, where the stylist had me scheduled for a $60 haircut. To paraphrase Mort Sahl, the idea of a $60 haircut on a 60-cent head is the perfect metaphor for a culture addled by vanity, but no matter. I had a job to do. My hairdresser was a Russian immigrant of undetermined age named Olga. Standing behind me, my head clamped between her hands like a hunk of modeling clay, Olga pulled and inspected wisps of hair as she studied the contours of my cranium in the mirror. Finally she declared in her thick Russian accent, “I’m going to make you look very dangerous.” As she snipped and shaped, Olga told me about her first husband back home and her new one in America. After about half an hour, she seemed satisfied. Again clamping my head between her hands, she nodded approval and said, “See? Dangerous.”

Inspecting my face in the mirror, I was dismayed to discover that she had coiffed my hair into a lopsided pouf that made me look alarmingly like Conan O’Brien. Dangerous? Actually, the word that sprang to mind was “deranged.” I held my tongue, however, and gave an indifferent nod. The stylist seemed pleased with the haircut, or at least relieved that I took it like a man.

From NorthPark we drove through dense fog to my next appointment, at the Osgood-O’Neil Salon on Snider Plaza, near SMU, where my eyebrows were to receive the attention of a certain Nicole. Before accepting this assignment, I had solicited a pledge from my editors that none of the day’s activities would cause me any physical pain. They had assured me that there was nothing to fear. But now I discovered that they were merely fobbing me off with half-truths. Nicole sat me in a chair and began to pluck out my eyebrows with tweezers. “Ouch!” I yelped, loud enough for the stylist to hear from across the room. “Tell my swine editors they will pay dearly for this.”

“It won’t hurt much,” she promised.

“Compared to what? Having my fingernails ripped out with pliers?” I squirmed, trying to dodge the insidious tweezers. “I’m fairly certain this is forbidden by the Geneva Conventions.”

This torture goes for $25. For an extra $10 I could have had my eyebrows tinted by a colorist. As we returned to the car, I was reminded of the remark of the man on death row: If it wasn’t for the honor, I’d just as soon forget the whole thing.

Over a disgustingly healthy lunch at a Snider Plaza deli, the stylist and I talked about how television shows like Extreme Makeover and Dr. 90210 have fostered the illusion that remolding the flesh is a duty rather than a luxury, at least among the very rich. Dr. 90210 is described as a “plastic surgery reality show.” Say that real slow and see what it does to your brain. I’d read in that morning’s New York Times a story titled “Putting Vanity on Hold.” Written by Natasha Singer, it related how the once booming microeconomy of beauty maintenance and body modification was suffering shamefully from the recession. Plastic surgeons were experiencing so many cancellations that they actually had time for golf. Back when everyone was flush and self-esteem was priceless, wrote Singer, “the body became the new attire, a mutable status symbol subject to trends in proportion, silhouette, technology and disposable income.” Now that families were having to choose between face-lifts, tummy tucks, and, say, mortgage payments on the McMansion, cosmetic surgery was becoming “the new S.U.V.,” a luxury that women (or their husbands) were discovering they could do without. Women were rising to the challenge by ditching personal trainers and joining gyms instead. Imagine that. One woman told Singer that she had recently started wearing bangs, a camouflage technique that allowed for fewer Botox injections. The stylist admitted that her own business was feeling the pinch. “Fewer husbands are calling to set up shopping trips for their wives,” she told me. “They don’t want their wives shopping, period.”

At a salon on the sixteenth floor of the W Hotel, just south of downtown, I changed into a robe and flip-flops for a facial, a manicure, and a pedicure. This was uncharted territory for me, as I suspect it would be for many men. In the three salons and spas I visited during that unforgettable day, I did not encounter a single member of the male species. I wonder if I was the first man ever to set foot in that perfumed sanctuary where people talked in soft voices and the only sound was “Greensleeves” lilting almost imperceptibly from hidden speakers. Sophia, a nail technician, assured me that that was not the case. “More and more men are coming in,” she said. “If they are embarrassed, I tell them we have a back door.”

I asked how business was. Sophia looked around to make sure our conversation was not being monitored. “Awful,” she whispered. “A year ago I’d be busy all day Saturday. Now I mostly sit and wait.” Born in Cambodia, Sophia escaped the killing fields in 1979, at age six, and went to New York, where she learned to do nails. She arrived in Dallas five and a half years ago. “I’m just so happy to be alive,” she told me. “I love America.”

While enjoying the Hot Milk and Almond Pedicure, I watched the Fox News Channel on a flat-screen TV. Soon Sophia began taming back the knives that grew wildly from my toes. Very much the professional, she resisted the opportunity for sarcasm: Oh, I see you’ve been killing and disemboweling small mammals and fowl, sir. How wise in these difficult times!

Speaking of difficult times, the pedicure and manicure together cost $90. I didn’t ask the price to have my nails lacquered pink, but I’ll bet it’s a pretty penny.

The best part of the day was the facial, which I’m fairly certain I slept through. “Slept” is not completely accurate. It was more like an opium dream. I was able to hear questions from my aesthetician, an attractive Cuban American named Candance, and mumble responses, but there were long lapses when the only sound in the warm, dark room was the brittle rasp of what I believe was my own snoring. The magic of a really good nap is that you know you’re napping and the knowing doesn’t interfere with the doing.

The Homme Improvement facial, as this particular treatment was called, costs $160. It takes about 75 minutes and is amazingly soothing and nonthreatening. First Candance analyzed my skin type and applied some sort of peel to remove dead skin cells. This was followed by the application and removal of various creams, lotions, medicated gauzes, and hot and cold towels. I asked a few questions, and I recall Candance answering with phrases like “glycolic peel,” “enzyme peel,” “oxygen wrap,” and “calming balm.” I had no idea what she was talking about, much less what she was doing. The delicate scent of grapefruit—or was it peach?—conspired with another exotic odor, which Candance identified as shea nut butter. Covering my eyes with a mask of pulverized cucumbers, she gently massaged my face, fingers, and toes. Using an instrument that looked like a small perforated spoon, she scooped blackheads from my nose. Toward the end of the treatment, she sprayed my face with solutions of vitamin A, vitamin C, and vitamin E. The last time anyone treated me like that I was in diapers.

Wobbling back to the men’s locker room on legs that had forgotten their purpose, I saw in the mirror that my skin radiated a nuclear glow, as though it had been backlit for a Norman Rockwell Thanksgiving painting. At the same time, I was shocked to discover that the fancy coiffure I had acquired from Olga had been totally wrecked by the workover my scalp had endured for the facial. Wild sprigs of hair now shot off in all directions. Conan O’Brien had been upstaged by a comic character with his toe caught in a wall socket. I wet my hair in the sink and tried to tamp it down with a comb and the palms of my hands, but the hairdo was history. On an impulse, I found a razor and some shaving cream and scraped off the shaggy patches of facial hair that I had allowed to grow in recent months. This would be my personal contribution to the makeover, which, I could see now, was going to need all the help it could muster.

For the final act, I headed to the Victory Park Lane store of Duncan Quinn, a menswear designer who also has shops in New York and Los Angeles. Quinn, I’d read in a Manhattan-centric fashion magazine, is a British corporate lawyer and unabashed dandy whose shops have been likened to “a kind of stuffy suit department on acid, where hip downtown salesmen in eye-popping patterns impart the kind of unimaginable knowledge of stitching you’d expect to find further uptown, if not across the Pond.”

Quinn wasn’t in Dallas this particular day, but we were met at the door by a sharply dressed salesman named Corey who had selected from his rack a handmade, meticulously tailored blue-gray wool suit that retailed for $3,250. He paired the suit with a $295 light-blue shirt with French cuffs, sterling-silver cuff links with red ruby insets that cost $295, and a red-striped tie that went for $165. The stylist did her level best to fluff up my damp, limp hair, but it was a lost cause. The Quinn-fitted fops that I’d seen photographed in the magazine had posed with English bulldogs at their sides and one leg propped on the bumper of a Jaguar town car. But Corey handed me a freaky motorcycle helmet and an umbrella and stood me against a neutral backdrop, in a far corner of the shop. I focused on looking dangerous but ultimately decided instead that my best hope was to concentrate on not looking goofy. I don’t think it worked.

A fortnight after my “day of beauty,” as I put the finishing touches on this column, I can safely report that the makeover seems to have done no permanent damage. My hair is as untamed and pillow-whipped as ever. The radioactive facial glow has dulled, and a slovenly stubble of beard has taken root over my familiar bag of wrinkles and flakes. My nails have never looked better, but I must confess that I miss being able to shred a chicken with my toes. Oh, and the $3,250 suit and other fancy duds? Had to give them back. It was a Sarah Palin deal.

As for the lawsuit, I’m torn. I keep studying the before and after shots, wondering if I should call my lawyer or leave well enough alone. What do you think? If anyone out there has a strong feeling about my new look versus my old or knows of an island in the Bahamas that the owner would be willing to swap for a successful regional magazine based in Austin that I may soon acquire in court proceedings, let me know.