In the summer of 1991 West Texas barbecue guru C. B. “Stubb” Stubblefield got word that he’d been invited to appear on Late Night With David Letterman. Unfamiliar with the crotchety TV personality, the chef and restaurateur watched his talk show every night for three weeks to get a feel for him. His assessment of Letterman was simple. “Not a very nice man,” he told musician Joe Ely, one of his best friends from Lubbock. “He treats people really bad, but I’ve just about got him figured out.”

When the day came, Stubb’s approach to dealing with Letterman was a respectful form of intimidation wrapped in old-fashioned Lone Star charm. As if his towering frame and cowboy getup weren’t imposing enough, his greeting doubled as a warning. “The eyes of Texas are upon you, sir,” he said, as if to suggest that the whole state was watching, so you’d better behave yourself. For the next six minutes, Stubb garnered his share of laughs, with Letterman reluctantly playing the role of straight man. When Letterman asked about the ingredients of good barbecue, he jumped at the chance to serve up his stock response: “Love and happiness.”

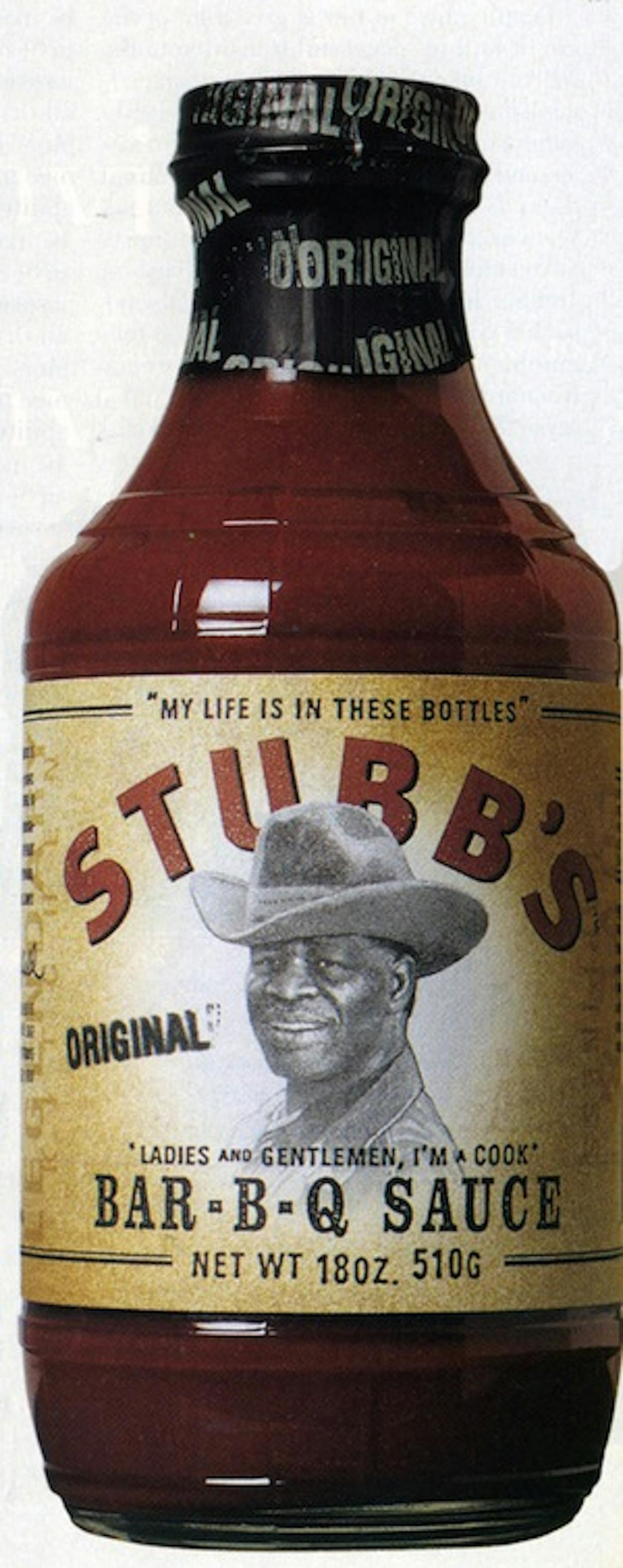

Stubb died in May 1995 at age 64, but his food empire, Stubb’s Legendary Kitchen, is still going strong. The tiny start-up that began eleven years ago with Stubb himself filling jam jars and empty whiskey bottles in the kitchen of Ely’s house now sells professionally packaged sauces, marinades, rubs, and liquid smoke in thousands of supermarkets in the U.S. and the United Kingdom—each product bearing his likeness and a simple declaration: “My Life Is in These Bottles.” It could just as easily be “We’re Number One.” In A. C. Nielsen surveys Stubb’s Original Bar-B-Q Sauce has been ranked the nation’s leading independent “specialty” sauce for two years running, topped only by “mainstream” brands like Kraft and K. C. Masterpiece. Sales of the entire Stubb’s line have been growing at a rate of nearly 70 percent a year—the privately held business reportedly took in more than $7 million in 1999—and could grow and could soon be growing even faster, thanks to a recent merger with the Austin-based Timpone’s family of organic spaghetti sauces, pastas, and salsas.

What makes the company’s record impressive is that it has carved out a niche in the highly competitive condiments market. A 1997 Kraft Foods study estimates the barbecue sauce category logs $336 million in sales annually, with 60 percent of U.S. households buying sauce at least once a year. Kraft, which sells nearly 45 percent of all barbecue products, is part of a small group of major manufacturers that account for more than 70 percent of shelf space in groceries; hundreds of specialty and regional barbecue sauces battle for what’s left. “It’s a pretty diversified field,” says Susan Friedman, the editorial director of Food Distribution Magazine. “These days, having a history behind the product helps immensely. What Stubb’s has done is create a bit of theater. They’ve got a story and the packaging to make somebody pull their sauce off the shelf for the first time.”

That history verges on genuine West Texas folklore. Stubb’s father, Christopher Columbus Stubblefield, an East Texas preacher, moved his family to Lubbock in the thirties so his nine sons could earn a living picking cotton. During the Korean War, Stubb served in the all-black 96th Field Artillery Battalion and cooked for thousands of soldiers daily. His original Lubbock restaurant, Stubb’s Bar-B-Q, opened in 1968 on the town’s predominantly black east side; though it served a culturally diverse customer base, it was best known for playing host to jams by up-and-coming musicians like Ely and Jimmie Dale Gilmore and intimate sets by blues mainstays like Muddy Waters and John Lee Hooker. “He was like a father figure to us,” Ely says. “He had a heart of gold. Any money he made he’d wind up giving away.”

In the late eighties Stubb followed many of his musician pals to Austin. After a heart attack left him broke and nearly homeless in 1989, Ely’s wife, Sharon, and singer-songwriter Kimmie Rhodes told him that if he bottled his sauce, they’d buy it and send it around the country as presents. Before long, 23-year-old Lubbock native John Scott—a financial analyst living in New York—and two friends, Scott Jensen and Eddie Patterson, began rounding up investors and sending Stubb checks for $5,000 and $10,000 every few months so that he could continue working out of a rented room on Ben White Boulevard. In 1991, hoping to create a steady income stream for Stubb, the trio incorporated Stubb’s Legendary Kitchen. Unfortunately, the start-up was more costly than anyone imagined, partly because Stubb would buy his ingredients from supermarkets at retail prices. “As we progressively lost more and more money, we started getting serious about what it would take to make it work,” says Scott, who estimates that Stubb’s Legendary Kitchen sold only $8,000 worth of sauce in its first year.

In 1992 Stubb agreed to move his production facilities to a commercial plant in Dallas—where he started buying tomato paste by the truckload instead of the ounce, eventually bringing the cost of a case of sauce down from $40 to $11—and Jensen and Patterson signed on as the company’s first full-time salespeople. They lived in a small four-bedroom house in Austin, working out of a small office on the second floor (Scott would fly into town on the weekends). Their initial goal was to capture 10 percent of the Texas barbecue sauce market and 1 percent of the national market, but they’d underestimated how difficult it would be just to get their product onto supermarket shelves. Texas-based H-E-B and Whole Foods initially refused to stock what was then an unproven barbecue sauce. “If we couldn’t get into H-E-B, the grocer in our own back yard, how could we convince anybody else?” Scott says. “All the doors were slamming in our faces.”

A letter-writing campaign finally got the trio an invitation to meet with H-E-B buyers, who—after devouring an impromptu lunch cooked by Stubb himself—recommended that they cut deals with local distributors instead of going directly to supermarkets. It made sense, really: Rather than ordering from hundreds of small companies, grocery chains routinely deal with distributors, who secure shelf space and promote the products they represent through in-store demonstrations, coupons, and giveaways. Today, Stubb’s and Timpone’s do business with nearly seventy distributors worldwide. “Attempting to go direct was our single biggest mistake early on,” Jensen says. “Had we known about the distributors all along, we’d be a year and a half further along right now.”

According to Scott, the company’s annual gross sales rose to $100,000 the second year, $300,000 the third, and $700,000 the fourth. By that year the founders were confident enough to look into building an Austin restaurant. It had been Stubb’s dream to open another barbecue-joint-cum-live-music-venue, and it would clearly be good for business to have a place to schmooze grocery distributors. But not long after they closed on a downtown lot, they suffered their biggest personal and professional setback: Stubb died in his sleep. “We wanted so bad for him to walk in, claim his table, and hang his hat,” Scott says. “Instead, overnight, we lost our best friend and founder. We went though a period of asking ourselves, ‘Can we do this? Can we survive without the guy who’s not only on the label but also inside the bottle?'”

After consulting with Stubb’s heirs and longtime friends, the founders and their partner in the restaurant, Charles Attal, agreed to move forward with their plans. Not that it would be easy: Stubb used to say that barbecue is color-blind, but the idea of a bunch of white Gen Xers in control of his legacy naturally raised suspicion; it would look like they bought and exploited his image after he died. “Just after his death,” Scott says, “when we’d present products to buyers, they’d make cracks like, ‘Oh, your picture’s on the label.’ It was insulting. We had such a deep connection.”

The hardest part, however, has been guessing what their notoriously unpredictable and stubborn founder might have done in certain business situations. Jensen says the governing rule is, What Would Stubb Do? Often the answer is easy: He wouldn’t water down the sauce or use thickening agents, he wouldn’t use inferior meats, and he wouldn’t control portions at the restaurant to increase profitability — so they haven’t. Five years later, that approach has paid off; not only is the restaurant profitable, they say, but its connected live music venues (a three-hundred-seat indoor room and a two-thousand-capacity outdoor facility) are regarded as two of Austin’s best.

Getting the Stubb’s Legendary Kitchen line in the black has been more problematic. Food Distribution‘s Friedman says that one of the dominant obstacles to profitability in the grocery industry is the “slotting fee,” the amount that manufacturers or distributors must pay to individual stores in exchange for shelf space. It works like this: If a chain agrees to carry a product line, the suppliers are charged a certain amount per product per store on a one-time basis. In addition, most stores demand that suppliers create a six- to nine-month advertising and promotional plan equal in value to the cost of the initial slotting fee. “Unless you have a lot of money, you can’t compete,” says Friedman. For smaller, relatively new companies like Stubb’s, the slotting fee issue is compounded by the fact that distributors pocket an additional 20 to 30 percent of the selling price. Supermarkets take a substantial cut as well, because specialty products have a slower turnover. Still, Stubb’s approach has been to buy as much space as possible where it makes sense and to spend whatever marketing dollars are available to hold on to it. “Growth costs money,” Scott says.

That was the underlying reason behind the December 1999 merger with Timpone’s; it wasn’t an easy decision for the founders, who would have preferred to go it alone, but they see an opportunity to create new markets for their products, to kick-start profits, and to transfer much of their production to the Timpone’s factory in Austin, a move that would save money by increasing productivity and decreasing shipping costs. The merger should also yield a balanced cash flow. Stubb’s products sell four times better from April to August than during the remainder of the year, whereas Timpone’s sells more sauce in the winter. And Stubb’s expects to enlist distributors to take Timpone’s products to major groceries and for Timpone’s to strengthen Stubb’s presence in the natural foods market.

Stubb surely would have approved of the merger, Scott says: On one of his first trips from New York to Austin, Stubb took him, Jensen, and Patterson to the Timpone’s kitchen and said, “We can do it just like this.” If only he were alive to see it, along with the rise of the cable food networks, which could have capitalized on his quick wit and long history in the kitchen. “He was such a great figure,” Ely says. “He could have been the Colonel Sanders of barbecuing.”