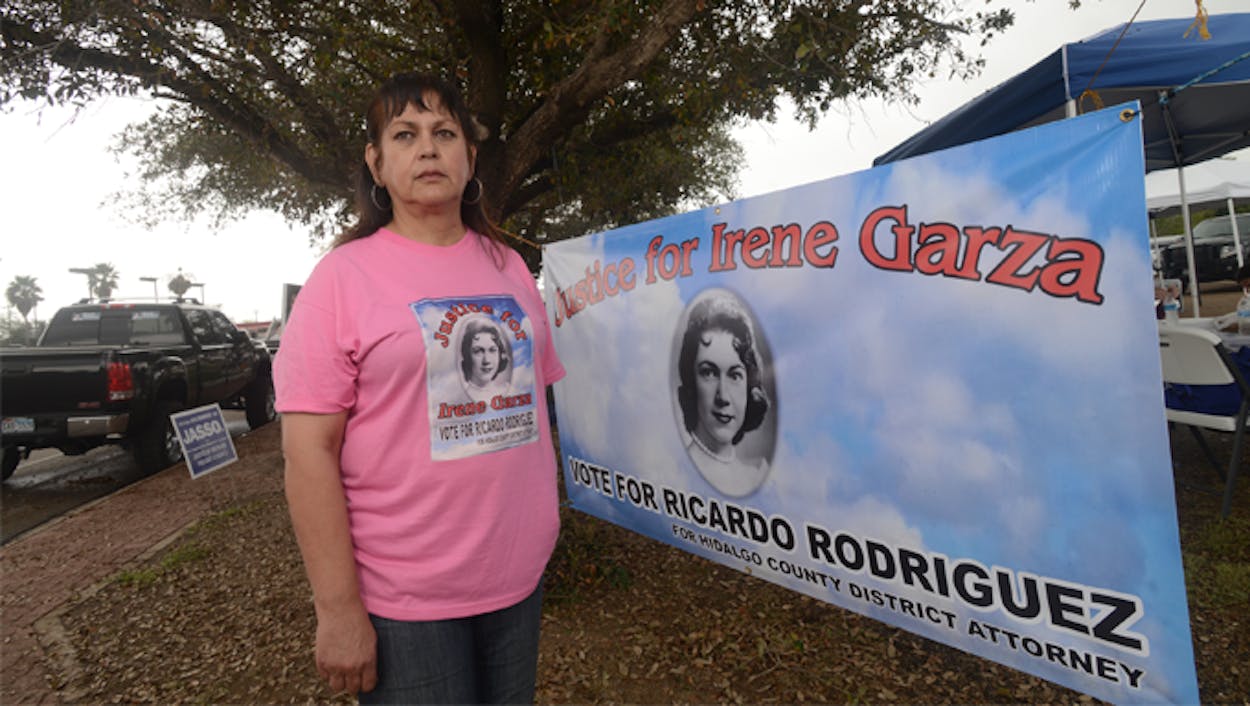

At a recent campaign event for Ricardo Rodriguez, a former district judge who is running to replace Rene Guerra as Hidalgo County’s district attorney, Edinburg mayor Richard Garcia took to the podium to warm up an already enthusiastic crowd. Garcia offered boilerplate campaign rhetoric, trumpeting the 41-year-old candidate’s accomplishments and his desire to bring sweeping change to the DA’s office. But near the end of his statements, Garcia brought up Irene Garza, a young woman from McAllen who was murdered nearly 54 years ago. Garza’s killer has never been prosecuted, and the mere mention of her name moved the spectators. “How many of you want justice for Irene Garza and all the rest of us here?” he said to a deafening cheer. “Enough said,” Garcia added, smiling.

It may seem strange that a half-century-old cold case could elicit such a strong reaction, but the memory of Irene’s murder haunts the Valley. More than five decades after her body was pulled from an irrigation canal, there is still only one suspect: the priest who heard her final confession.

Irene led a short but remarkable life. At McAllen High School, where Anglos were the majority, she was the first Hispanic twirler and head drum majorette. She was the first person in her family to attend college and graduate school. A former prom and homecoming queen at Pan American College, she was crowned Miss All South Texas Sweetheart 1958. At the time of her death, she was a 25-year-old schoolteacher who worked with McAllen’s poorest children. She spent her first paycheck on them, buying them books and clothes.

On April 16, 1960, Irene borrowed the family car to drive to Sacred Heart Church, where she planned to go to confession. As she walked out the door, around 6:30 that evening, she promised her mother she would not be long. A number of parishioners saw her at the church that evening, but no one saw her leave. The next morning, Easter Sunday, her car was still parked down the street.

Four days later, her body was found floating in a nearby canal. An autopsy determined that she had been bludgeoned and suffocated. According to her death certificate, she was raped while in a coma.

The exhaustive investigation that followed turned up one prime suspect: Father John Feit. The 27-year-old priest admitted that he had heard Irene’s confession that evening, and that he had done so in the privacy of the rectory rather than the confessional. There were other odd details. Several churchgoers who stood in his stalled confession line that night told detectives that he seemed to have been absent from the sanctuary for long periods of time. Another priest, Father Joseph O’Brien, reported seeing conspicuous scratches on Feit’s hands when they drank coffee together after midnight mass.

Investigators’ interest in Feit only deepened after they dragged the portion of the canal where Irene’s body appeared to have been dumped. There, they made an intriguing discovery. Lying on the bottom of the canal was an Eastman Kodaslide viewer with a black cord—a cord long enough to have bound together Irene’s hands. Police appealed to the public for help in finding its owner. Two days later, Feit stepped forward and said that he had purchased it the previous summer at a local drugstore.

Detectives also discovered that a priest who closely fit Feit’s description had attacked a young woman named Maria America Guerra inside a church in nearby Edinburg two weeks before Irene’s disappearance. Curiously, Feit did not deny being in the church that afternoon or even driving the same car that the attacker was spotted in. But he insisted that he had left Edinburg at least an hour before the attack. He flunked a subsequent polygraph test, which “definitely implicated him in both crimes,” read the report. “The subject was not telling the truth when he denied killing Irene Garza or attacking Maria Guerra.”

In the summer of 1960 Feit was indicted for “assault with intent to rape” Guerra. He was declared a fugitive when church officials told arresting officers that he had left the state. The priest later surrendered, claiming that he had suffered a nervous breakdown brought on by the police interrogations, and stood trial the following year. The jury deadlocked nine to three in favor of conviction, and the proceedings ended in a mistrial. In 1962 Feit pleaded no contest to reduced charges of aggravated assault and was fined $500. And that was it. No charges were ever filed against Feit for Irene’s murder.

As I wrote nine years ago in a lengthy article about the case (“Unholy Act,” April 2005), people wondered whether a deal had been struck between the church and the DA’s office, or if the elected officials in the overwhelmingly Catholic town were afraid to challenge the church any more than they already had. Irene’s parents, Nick and Josefina Garza, who would both pass away without seeing anyone prosecuted for their daughter’s murder—and who had suspected Feit from the outset—were assured by Father O’Brien that the young priest would be sent to a monastery and kept away from the public. As Josefina’s sister Herlinda de la Viña told me in 2005, “Who were we to question a priest?”

When the Texas Rangers’ cold-case unit reopened the case four decades later, in 2002, its investigators turned up even more compelling evidence. A former priest from Oklahoma City named Dale Tacheny came forward to say that during his time at a Trappist monastery in Missouri in the sixties a young priest from Texas had told him of murdering a woman. According to Tacheny, the young priest said that one year during Holy Week, he had taken the woman to the parish house of her church to hear her confession. Then he assaulted, bound, and gagged her. Later, he put a bag over her head, suffocated her, and dumped her body by a canal. The priest, Tacheny said, was named John Feit.

The Rangers also interviewed Father O’Brien, who said that he had suspected Feit of Irene’s murder from the start. Under further questioning, he told the Rangers that a few months after the murder, he had confronted Feit about whether he had killed Irene, and the priest had told him everything. O’Brien said he would disclose exactly what Feit, who lived in Phoenix by this time, had told him if he were called to testify before a grand jury.

But that never happened. Hidalgo County DA Rene Guerra (no relation to Maria America Guerra) refused to take the substantial evidence that the Rangers had amassed to a grand jury, citing that it was insufficient. Without DNA or a confession, Guerra said, he could not take such an old case to trial. “I reviewed the file some years back; there was nothing there,” he told the Brownsville Herald in 2002. “Can it be solved? Well, I guess if you believe that pigs can fly, anything is possible.” What he said next wounded Irene’s family even more. “Why would anyone be haunted by her death?” he said. “She died. Her killer got away.”

Local media pounced on the story. “I wonder if he thinks he would be excommunicated if he took the case to a grand jury?” retired police investigator Sonny Miller quipped to reporters. After tremendous negative publicity, Guerra finally agreed to have two of his prosecutors present evidence to a grand jury in 2004. But the DA’s office hardly seemed invested in obtaining an indictment. The Texas Rangers were not called to testify until the proceedings were nearly over. Stranger still, Dale Tacheny and Father O’Brien were never called at all. Nor was Feit ever subpoenaed to appear before the grand jury, which would have compelled him to either testify, or invoke his Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination. On June 9, 2004, the jury declined to indict him and no-billed the case.

And so the case once again hit another brick wall. Father O’Brien died in 2005, having never had the opportunity to recount to a grand jury what Feit had told him. Witnesses died, and others grew older. Guerra clearly had no interest in pursuing the case any futher, so when he announced last year that he would be seeking a ninth term—he has been the Hidalgo County DA for no less than 32 years—Irene’s family had all but given up hope of ever seeing Feit tried for her murder.

That changed when Ricardo Rodriguez stepped forward to challenge the 68-year-old Guerra in the Democratic primary. Guerra has had challengers before, but none who were able to unseat the man who is considered the most powerful person in Hidalgo County. (Detractors like to joke, “¿Es el rey o el DA?” or, “Is he the king or the DA?”) But the popular and well-connected Rodriguez, who stepped down from the bench last year to run, is Guerra’s most formidable opponent yet.

When Rodriguez announced his candidacy last fall, he did not mince words. If elected, he said, he would not “threaten and silence those who are not in political favor.” He added that he had “heard many stories from Hidalgo County residents and families who have suffered many years and many injustices at the hands and at the whim of our present district attorney. Our present district attorney imparts justice and bases decisions not on the fundamental tenets on which this country is based, but rather on his arbitrary beliefs, as when he tells someone that justice will be dispensed when pigs fly.”

The reference to Irene’s case was not an accident. Rodriguez has met several times with Irene’s family, and her relatives were present at his announcement. “I have not been privy to the actual, physical case file,” Rodriguez cautioned when I spoke with him last week, “but the fact that the Texas Rangers and the McAllen police department wanted to see this case prosecuted, and then it wasn’t, tells me that something wasn’t done right.” If elected, he said, he would review the case file and determine whether all the available evidence had been presented to the grand jury. If not, he said, he would consider presenting it to a grand jury again, with a full airing of all the available evidence.

The son of migrant workers, Rodriguez has a compelling life story. He worked in the fields until he was eighteen then put himself through the University of Texas at San Antonio and the Thurgood Marshall School of Law at Texas Southern University. He returned to the Rio Grande Valley, where he was elected to the Edinburg city council. He was then elected state district judge when he was just 33.

Although the Garza case is more than half a century old, it has been “a big issue” on the campaign trail, he told me. “I hear about it every day,” he said. “Even young people ask me about the case. When I visited the University of Texas-Pan American recently, the students asked me, ‘Why? Why was this case treated this way?’”

In heavily Democratic Hidalgo County, the primary election, which occurs next Tuesday, will effectively decide the race’s winner. Much hangs in the balance for Irene’s family, since the case’s star witness, Dale Tacheny, is now 84 years old. Feit, who left the priesthood in 1972 and went on to live a quiet life in Phoenix, is now 81.

What is Feit like now? The CBS News program 48 Hours—which will devote an upcoming broadcast to Irene’s case—shows the former priest in what might generously be called an unguarded moment. (Full disclosure: I worked as a consultant on the episode.) When CBS News correspondent Richard Schlesinger tracked Feit down in Phoenix and began asking him about Irene, he responded this way:

Feit Confrontation from Texas Monthly on Vimeo.

The 48 Hours broadcast—a comprehensive look at the case that was many months in the making—will air at 9 p.m., central standard time, on Saturday, March 1.

Irene’s family members are hopeful that the show will be widely watched in Hidalgo County. They have been trying, on their own, to rally support for Rodriguez before the election. Irene’s first cousin Lynda de la Viña wrote an impassioned letter to the McAllen Monitor last week in which she talked about Guerra’s insensitivity to her family and his refusal to pursue charges against Feit. Her letter read, in part:

In essence he said that no one cared [about this case]. But really, it was he who didn’t care. We cared. We were there through the days of terror before her body was found; through the days of sorrow after her death; through the days of hope that her killer would come to justice; and through the years that followed of dismay and frustration with the district attorney. We have cared for 53 years. We have been pained for 53 years, and we have been patient for 53 years. . . . We care about violence against women. We care that those from the highest to the lowest stations in life receive the same equal dignity and attention that is merited by our legal system. I do not believe that Guerra cares.

In closing, she wrote, “Cast your vote for Judge Ricardo Rodriguez for district attorney. Judge Rodriguez cares!”

This weekend, a member of Irene’s family by marriage, Noemi Sigler, plans to hold a press conference for local media at which Tacheny—who will travel to the Valley from Oklahoma City—is expected to speak. Sigler and de la Viña feel that such attention is critical in the days leading up to the primary. This may be the last chance they have to see anything happen to Feit. “People say to me, ‘Well, he’s already so old,” de la Viña said. “And I say, ‘What does that matter?’ No matter how many years have passed, we still want justice for Irene.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Crime