This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

On August 20, Racehorse Haynes, the noted criminal defense attorney, was enjoying a quiet Sunday on his sailboat and perhaps wondering what his most lucrative client, T. Cullen Davis, was up to these days. When the ship-to-shore radio crackled, he found out: Cullen was being arrested and charged with hiring a hit man to kill his divorce judge, Joe Eidson.

“I don’t have the foggiest notion what’s going on,” Haynes told the reporter who had called with the news. The reporter gave him the sketchy details: David McCrory had gone to the FBI with a story that Cullen planned to hire the killing of fifteen people; the FBI staged the judge’s murder and took photographs of Eidson’s body curled up in the trunk of a car, then made a videotape as Cullen allegedly paid McCrory $25,000. “Is this the same McCrory who was involved in Amarillo?” Haynes asked. It was. “It’s curious,” Haynes said.

And it got curiouser and curiouser. The state’s evidence included four tapes of McCrory and Cullen talking about murders and hit men, $25,000 in cash, the faked photo of the judge’s body, and a .22 pistol equipped with an illegal silencer. By Sunday night Haynes and the other members of Cullen Davis’ blue-ribbon defense team were reassembled in Fort Worth, where they had started on Davis’ legal odyssey almost exactly two years before.

Haynes was never much inclined to float on his laurels, but since winning Cullen Davis’ acquittal in Amarillo, where Cullen was on trial for the murder of his wife’s boyfriend and her daughter by another marriage, some of Haynes’ old fire seemed to be missing. It had been a brilliant victory, adding to his fortune and assuring his fame: Haynes was now being mentioned in the company of Percy Foreman, F. Lee Bailey, and Edward Bennett Williams. But fame had certain drawbacks. It was harder now to pick a jury. Too many people knew his reputation and were suspicious; there is something about lawyers with high-blown reputations that conjures up images of warlocks. Nor did the constant demands on his time help his concentration. Only a few weeks earlier, as he was working on Cullen’s divorce case and at the same time defending another client accused of murder, Haynes caught himself in an uncharacteristic lapse. During the voir dire of the murder case, Racehorse asked a potential juror if he believed in community property. My God, he thought as soon as he’d asked the question, wrong trial! Haynes’ client was convicted. Haynes had been beaten by a young Tarrant County prosecutor. He must have wondered if he were slipping.

News of Cullen’s latest plight may have shocked Haynes back to reality, because Race arrived in Fort Worth like Eddie Stanky sliding cleats-high into second base. At the heart of the prosecution’s case were the four highly incriminating tapes, including the segment in which McCrory said, “I got Judge Eidson dead for you,” to which Cullen Davis replied in a clear, calm voice: “Good.” Haynes knew that recorded conversations were not automatic proof of guilt, but as physical evidence went, these tapes were pretty formidable.

The state’s fatal weakness in the Amarillo murder trial had been the lack of physical evidence. No fingerprints, no murder weapon, only the testimony of three eyewitnesses. Haynes ate eyewitnesses for breakfast. In any case where there were eyewitnesses, Haynes’ first line of defense was to discredit them. If the tactic failed, and it seldom did, Haynes’ second line was an alibi. If this failed, he attacked the physical evidence, bombarding the jury with a mind-boggling amount of expertise on ballistics, pathology, internal medicine, psychology, crime-scene investigative techniques—not to mention law. Finally, if all else failed, Haynes resorted to the technique used by all great criminal attorneys. Skeptics call it the Ultimate Lie technique. Warren Burnett, the celebrated Odessa lawyer, was once called on to defend a fellow who drove his car through the front door of a tavern where he had drunk every night for forty years; he won acquittal when his client testified that he’d never been in that tavern in his life.

In Amarillo, Haynes had defended Cullen Davis by prosecuting the eyewitnesses, especially Priscilla Davis. By the second week of the thirteen-week trial, the jury was ready to stone her. For the next eleven weeks Haynes unraveled a number of simultaneous scenarios designed to take the jurors’ minds off the fact that Cullen Davis was accused of the murders of Andrea Wilborn and Stan Farr and to get them to focus instead on the theory that any number of “phantoms” could have committed the crime. But most observers agreed later that the case was won as soon as Haynes completed his cross-examination of Priscilla, “the queen bee . . . the other-worlder . . . the Dr. Jekyll and Mrs. Hyde . . . the lady in the la-di-da pinafore.” Race and his associates, Phil Burleson, Mike Gibson, and Steve Sumner, formulated the “second-worlder” scenario early in the trial. It explained how Priscilla’s addiction to the painkiller Percodan enabled her both to rub elbows with the elite of Fort Worth and to hobnob with its drug dealers and low-life criminals; it explained how she could easily have been confused when she identified Cullen Davis as the killer. Haynes had called in an expert on drug addiction, Dr. Robert Miller, who told the jury that, yes, indeed, “second-worlders” frequently got their facts confused.

Though Haynes usually disavows the value of showboating in front of a jury, he didn’t resist many opportunities in Amarillo. Sometimes he did it with a glance at the jury box. Did you hear what she said? When he caught a witness in an inconsistency, Haynes dug out some previous transcript, approached the witness stand like a missionary accustomed to dealing with pygmies, pointed to the conflicting statement, and said very softly: “Now, don’t you remember saying that way back there?” Sometimes he did it with props, like the famous photograph of Priscilla and W.T. Rufner, the one where “T-man” posed naked except for a Christmas stocking covering his genitals. Though the picture was never admitted into evidence, the jury was able to see it quite clearly, since Racehorse had printed it on nearly transparent paper. And sometimes he did it with wondrous phrasing, the innuendo clinging to his lips like feathers. The Rufner scenario was largely designed to convince the jury that Priscilla, the two-worlder, the queen bee, enticed her daughter Dee and other teenage girls into drug-and-sex orgies with disreputable men twice their age, many of them convicted drug dealers. Valerie Marazzi, one of Dee Davis’ teenage friends, told the jury of an evening when she, Priscilla, Rufner, and Larry Myers were all naked in Myers’ bed. T-man got the idea they ought to change partners, Valerie said, so Priscilla crawled over on Myers’ side of the bed. Valerie and Rufner watched while the other couple had sexual intercourse.

HAYNES: And as a consequence of that situation . . . what did W.T. Rufner do?

MARAZZI: He apparently got jealous and poured a drink on her.

HAYNES: Was she still in criminis particeps?

MARAZZI: Huh?

HAYNES: Were they still doing it?

MARAZZI: Yes, sir, they were.

None of the prosecutors objected to criminis particeps. Maybe they didn’t know what it meant either. It charmed the jury, though. They could well imagine Priscilla participating in that sort of criminis.

Haynes claimed his hardest decision in Amarillo had been whether to call Cullen Davis to the stand, but he decided not to. “I thought about it drunk and sober,” he said. It haunted his dreams. Haynes remembered the Gus Mutscher trial. After a night of agony, he had decided not to call Mutscher to the stand. The former Speaker of the Texas House of Representatives was convicted. “What it boils down to,” Haynes said, “is that you have to trust the jury. It’s hard to do. You want to trust yourself, but there are times when the back of your neck says stop now, you don’t need anymore, don’t second-guess, trust the jury!” It’s possible that Haynes exaggerated his agony over Cullen Davis. He had trusted that jury all the way.

When the jury announced its verdict after less than five hours of deliberation, there were tears in Haynes’ eyes and his voice was a hoarse, cracked whisper. It was probably the greatest victory of his career, though not necessarily the greatest moment of his life. Members of the jury made it clear that though they had acquitted Cullen Davis, this didn’t necessarily mean he was innocent. There is a slight but perceptible difference. Under the law the jury is bound to acquit a defendant if it has a reasonable doubt of his guilt. Haynes had planted the doubt. It had taken thirteen weeks, many times the length of the average murder trial; Haynes had deliberately prolonged it until he was certain all twelve jurors had a reasonable doubt. He hadn’t anticipated it would take that long, otherwise he would probably have asked for much more than his flat fee of $250,000. Phil Burleson’s law firm, working on an hourly basis, billed the client for $1.5 million.

Nine months after Amarillo, when Haynes learned that Cullen was once again in the clink and that David McCrory was the state’s key witness, the old juices started flowing again. McCrory was a proven liar. Originally, he had been the defense’s bombshell witness in the murder case, charging Priscilla with a number of unsavory acts and pointing the finger of suspicion at W.T. Rufner, but McCrory later refuted the defense affidavit line by line. Haynes had been cited for contempt of court when he entered McCrory’s unsigned affidavit in the court record. This was easily Racehorse’s most embarrassing moment in the entire Cullen Davis affair, and the proud Houston lawyer had not forgotten. The tapes were going to be a problem, but Haynes looked forward to his confrontation with McCrory. He quickly formulated a scenario in which McCrory, Priscilla, and a mutual friend, Pat Burleson, had conspired to frame Cullen on the new charge.

For several days Haynes argued that the case should be tried in Fort Worth (where Cullen was now a genuine hero and where Priscilla’s name was usually spoken with a sneer). The judge disagreed with Haynes’ argument and ordered the trial moved to the 184th District Court in Houston. The 184th was presided over by Judge Wallace “Pete” Moore, Race’s longtime close friend. Pete Moore is frequently cited as an extraordinarily fair man by lawyers who have appeared in his court.

“He’s an A-number-one guy,” Haynes smiled. “A very able lawyer and a very able judge.”

It was the best-seller Blood and Money that got Haynes his first small measure of national recognition and, at the same time, introduced him to Cullen Davis. That was back in the summer of 1976. Cullen didn’t read a lot of books but he read this one. It was written by an old Arlington Heights High School classmate, Tommy Thompson, who had been the speaker and celebrity at a class reunion two months before the murders.

Haynes was at a bar association barbecue in Fort Worth when he first heard of the plight of T. Cullen Davis. Race thought maybe he had met Davis at a party years ago when they were both in college, but he wasn’t sure. In August 1976, Haynes was just a lawyer for hire—at a substantial fee, he hastened to add, and only on those select cases that intrigued and challenged him and stimulated his private pleasure in dealing with il mondo weirdo. He’d defended a motorcycle gang accused of nailing a woman follower to a tree, Houston cops charged with kicking a prisoner to death, the Speaker of the Texas House of Representatives, and the Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan. All he really knew about Cullen Davis at that point was that he owned a $6 million mansion and was charged with murder. “Television sold a six-million-dollar man,” Haynes said. “That gets you a little bit interested, right?” It came as no surprise when someone at the bar association barbecue got word to Cullen’s jail cell that Racehorse Haynes was interested in his plight.

Early in his life Richard Haynes had dreamed of being a decathlon athlete. He wanted to do it all—faster, stronger, higher, and with more skill and endurance than anyone had done it before. A plaster’s son who grew up in a tough, blue-collar enclave of North Houston, Haynes was built like a refrigerator. “I grew up to be a midget,” he claimed. But he didn’t remind anyone of a midget. Long before he became a famous attorney, Haynes could fill a room with his mere presence. People sensed that he was a fierce competitor. A nose that spread over his face like the blade of a bulldozer showed that he didn’t back away from fights.

As an eighteen-year-old he was Texas Amateur Athletic Federation welterweight boxing champion, and he was known as a battering-ram running back at Houston’s Reagan High School. The name Racehorse was originally a slur directed at him by a junior-high football coach who was chiding his habit of running toward the sideline. “What do you think you are,” the coach rebuked him in front of his teammates, “a racehorse?” The name stuck, not without Haynes’ encouragement. He liked the name, liked the image it connoted—fast, sleek, ready for the distance.

He liked the fact that he was a self-made man. There had never been a professional man in his family, and Haynes had joined the paratroopers with the idea of making a career in the military. An accidental encounter turned him to the practice of law. A young enlisted man from his company was accused of stealing food from the mess hall. Race knew a little about law—he used to cut class in college to watch Percy Foreman perform his fire-belching magic—and he was appointed to defend the accused food thief. In those days the Uniform Code of Military Justice didn’t provide the accused with a genuine attorney in misdemeanor cases. Nor did it prohibit hearsay evidence. Haynes’ client was convicted on the testimony of a witness who told the court what a sergeant had told him someone else had said. “I checked the book,” Haynes recalled. “That was called hearsay twice removed. I brought this up to the major who was the presiding officer at the court-martial, but he said, ‘Naw, if the witness said he heard the sergeant say that’s what he heard, it’s admissible.’ The kid was selectively prosecuted, then convicted on double hearsay. The inequity of that situation fired me up to the point that I decided to head for law school.”

In 1954, Haynes returned to Houston and entered the University of Houston law school, supporting himself with the GI Bill and an assortment of odd jobs that included life-guarding and hustling golf. He was already married (Race and his wife Naomi have been married 28 years) and Naomi also worked full-time. Race already understood the value of publicity. He was elected student body president after a story circulated around campus that he had announced his campaign by parachuting out of an airplane into the campus reflecting pool. It never happened, but it was some years before Haynes got around to setting the record straight. People still swear they saw him jump. Years later people would perpetuate another myth: that Haynes won acquittal for the motorcycle gang accused of nailing a woman follower to a tree by nailing his own anesthetized hand to the jury box. To win the “Crucifixion Case” (Race claims he took it because it was the first crucifixion case to come along in 2000 years), Haynes was no doubt prepared to drive a nail through his hand. “I’ve always regretted that my case was so strong I was able to win without doing that,” he says.

The mythical parachute jump got Haynes his first case. Some University of Houston students charged with violating the state’s tough laws against open saloons had heard the myth and hired Racehorse to defend them. The young lawyer went first to the law library, then to the medical library, where in a few days he made himself an expert on the subject of intoxication. He won the case. It was that expertise in intoxication that set him on his course. Over the next few years he built his practice by defending hundreds of clients accused of driving while intoxicated. In the early sixties he won 163 straight DWI cases.

From the beginning, Racehorse had devoted almost all of his attention to the defense of those accused of crimes. He didn’t have much wherewithal for prosecutors—prosecutors reminded him of the bullies he’d fought all his life—and he didn’t have the patience to handle personal injury suits. They took months, sometimes years, just to get on the docket. In most cases Haynes’ client couldn’t afford to wait, and neither could he. But there was something else about criminal law—it appealed to Haynes’ ego and incited that unnamed thrill of saving a fellow human from what Race calls the Crossbar Hilton.

The first felony case he ever tried involved a poor black charged with theft. The fee was $300 and he won acquittal. Haynes recalled: “As soon as we heard those words ‘Not guilty,’ ol’ Jesse was hugging me, his big fat wife was hugging me, his eight kids were hugging me, his relatives were slapping me on the back and saying ‘Thanks for saving Jesse’ and ‘Come on over for dinner.’ Then you go down to the bar where all the lawyers hang out. Everyone’s saying ‘Good going’ and ‘Attaboy!’ You don’t get that feeling winning money from an insurance company. It’s just a damned good feeling, you know? I like that.”

His mentor, Percy Foreman, impressed on Haynes the importance of the voir dire examination (the questioning of potential jurors by attorneys for both sides). “Know your jurors,” Foreman told Haynes—not just their names, ages, occupations, and religious preferences. Know their politics, their economic history, their family history, their medical history, their superstitions, their tolerance for human suffering, their ability to conceptualize and follow complex scenarios. “A jury is like a computer,” Haynes says. “Twelve components working together, scanning, observing, sworn to pay attention—a formidable machine!” Juries in criminal cases are required to render a unanimous verdict in order to convict. If Haynes picked his jury right, he felt he could convince at least one of the twelve that cobras make honey.

From his early success in defending clients accused of drunk driving, Haynes had learned that trials are not won by showboating in the courtroom—they are won through careful attention to detail and by hard scientific analysis of situations and evidence. Haynes prepares himself for a case by cramming down books and articles on criminology, pathology, ballistics, psychology, crime-scene investigative technique, whatever is called in for a particular case. “Many cases have been lost because some chemist bamboozled the defense attorney,” he says.

In the case of an aircraft mechanic accused of murdering an airline insurance clerk, Haynes made himself an expert on nuclear-activation analysis. The prosecution’s case hung literally by a hair recovered from the victim’s body. A scientist for the state analyzed the hair by a process known as nuclear activation and was prepared to tell the jury that the hair in question could be positively identified as belonging to Haynes’ client.

“I went to the library and made myself the world’s leading authority on nuclear-activation analysis,” Haynes recalls. “I convinced the judge that it just didn’t fit the legal requirements of that time for scientific evidence. The judge ruled that their scientist’s testimony was inadmissible. On the basis of the remaining evidence, the jury voted nine to three for acquittal.”

Race won another case by proving that the impact of an ornamental ball and chain on a human skull is insufficient to cause death. In still another case he snatched victory after interrogating an empty witness chair. When all else fails, Haynes is prepared to win on pure gall. He outlined the classic defense technique in a talk at an American Bar Association seminar: “Say you sue me because you claim my dog bit you. Well now, this is my defense: My dog doesn’t bite. And second, in the alternative, my dog was tied up that night. And third, I don’t believe you really got bit. And fourth [here he broke into a sly grin], I don’t have a dog.”

Haynes never goes into a courtroom depending on a single theory or point of law. It’s his style, his trademark in fact, to develop a number of simultaneous scenarios, each designed to cast doubt on his client’s guilt. When it comes time for his final argument, he picks the one that seems most likely to work.

A classic example was his defense of two Houston cops who were accused of kicking a black man to death after arresting him for attempting to “steal” his own car. The cops had already been acquitted by a district court in Houston—now they were being tried in federal court on charges that they had violated the man’s civil rights. For starters, Haynes got the trial moved from Houston to the conservative German American town of New Braunfels. “I knew we had that case won when we seated the last bigot on the jury,” Racehorse remarked later. As the trial progressed, Haynes developed these scenarios: (1) that the prisoner suffered severe internal injuries while trying to escape; (2) that he actually died of an overdose of morphine; (3) that the deep laceration in the victim’s liver was the result of a sloppy autopsy.

Haynes talks a lot about justice under the law, but in many ways he seems a tiny, tireless law unto himself. After Cullen’s Amarillo trial, chief prosecutor Joe Shannon, a former state legislator and a card-carrying conservative, remarked: “I never thought I’d hear myself say this, but it appears we do have two systems of law in this country. One for the rich and one for the poor.” Shannon believed that Haynes won the case because Judge George Dowlen permitted him to run wild with his many scenarios. Priscilla’s moral character shouldn’t have been an issue, but it was the issue that decided the case. If the situation had been reversed, if the state had done that sort of hatchet job on a witness, the verdict would have ended up in the trash can of some appeals court. The state, however, had no right to appeal, so defense attorneys run with as much rein as the trial judge allows them. Right or wrong, that’s the system. When judges are faced with a tough ruling, they are likely to err on the side of the defendant, knowing that is where the sympathies of the appeals court will lie. The longer a defense attorney can prolong a case, the more opportunities there are for the sorts of technical errors that lead to reversal on appeal. When a defendant has several hundred million dollars, a good lawyer can prolong a trial for months. Leon Jaworski believed that Richard Nixon could not be tried in this country. Haynes thought otherwise. Nixon could be tried, he just couldn’t be convicted, not with enough money and a lawyer like Racehorse Haynes to show him how to use it.

The Houston trial started on October 30. By November 3, Race knew he was in trouble. He couldn’t trust this jury for the unanticipated reason that he couldn’t trust this judge. His old friend Pete Moore was being obstinate. On the first day of pretrial, he reprimanded Haynes for being a few minutes late to court. He rushed the attorneys through jury selection in four and a half days, and when the lawyers warned the jury the trial might take five or six weeks, Moore interrupted and said: “It won’t take that long.” Haynes couldn’t believe his ears when the judge announced that he would tolerate no irrelevant testimony designated to assassinate the character of any witness. If Moore held to this mandate, their first line of defense was already in jeopardy. The master scenario—that Priscilla had framed Cullen in consort with David McCrory and Pat Burleson—depended on connecting the three “conspirators,” then hacking them into bloody pieces.

The defense hadn’t yet found a way to connect the three, except indirectly — Haynes could document that Priscilla and Burleson (a distant cousin of co-defense counsel Phil Burleson, though the two had never met) had a curious series of meetings shortly before Cullen’s arrest, as had Burleson and McCrory: Burleson put McCrory in touch with the FBI. Burleson was the link. But the state wasn’t going to call either Burleson or Priscilla, which meant Haynes couldn’t get his hands on them for cross-examination, when the witness is pretty much fair game. Of course the defense could call them, but Pete Moore wasn’t about to allow Haynes to impeach his own witnesses.

The second line of defense, the alibi, had no meaning in this particular case: there was no doubt that was Cullen Davis’ voice on those tapes, and there was no doubt the subject of conversation was murdering people. This also foreshadowed the third line of defense—attacking the authenticity of the evidence, in this case the tapes. What Race could attack was the intent of the tapes. Did Cullen really intend for Judge Eidson to die? Maybe Cullen was just playing along with McCrory. But why? Maybe to gain information to use against Priscilla in the divorce trial. It was an improbable scenario, but if the conspiracy theory wouldn’t travel it might be the only way out. Otherwise, the defense would be left with old number four, the Ultimate Lie—“I don’t have a dog.”

The prosecution was armed with a ton of evidence, particularly the tapes, but it was possible that the most telling piece of physical evidence was a piece they didn’t have—Cullen’s fingerprints. Not on the $25,000, not on the gun, and most embarrassingly not on the photograph of Eidson’s body that Cullen supposedly examined before making the payoff. The FBI had dusted the photo with fluorescent powder before sending McCrory to the August 20 payoff meeting. The powder should have collected in the ridges of Cullen Davis’ fingers and nailed shut the proverbial coffin lid, but in those dizzy hours after the arrest something happened that is only supposed to happen in dumb movies: unaware of the fluorescent powder, some well-meaning Fort Worth cop did a routine fingerprint make on Cullen, then instructed him to wash his hands with naphtha.

The prosecution downplayed McCrory’s role as a star witness, focusing instead on the tapes. McCrory was just there to corroborate the physical evidence. That was pretty much their case, and once the jury had listened to the tapes fifteen or twenty times, the state rested. Jack Strickland, the number two prosecutor, called the tapes “irrefutable” and for the time being that assessment appeared accurate. But Haynes reminded reporters that the system gave each side a turn at bat and their turn was coming.

“The opera ain’t over till the fat lady sings,” Haynes said, smiling while cleaning his half-moon glasses with a silk handkerchief and puffing on his pipe.

Race called as his first two witnesses the other alleged conspirators, Priscilla and Pat Burleson. The scenario depended upon Haynes exploring the longtime relationships and private lives of the three, but time after time Pete Moore ruled that Race’s barbed questions were irrelevant. Priscilla and McCrory both claimed they hadn’t seen each other in a year, and the fact they both knew Pat Burleson established nothing.

Pat Burleson proved to be a very able and patient witness; it was Haynes who appeared obstinate and unsure of his direction. About the best Race could do was to establish that Burleson wasn’t positive about the exact times of his meetings with Priscilla. In the bond hearing he said a meeting took place at 10 a.m., but now Burleson was telling the jury it took place around midmorning. “Well,” Haynes grilled him, “which was it?” Burleson looked at the jury, sighed, and said: “I guess midmorning.” Burleson confirmed Priscilla’s story that the meetings were to plan security for the upcoming divorce trial. The court had removed its order requiring that Cullen pay for Priscilla’s bodyguards and Burleson, a karate expert, was taking on the job himself.

Haynes tried every back-door tactic in his repertoire, but Pete Moore kept reminding the lawyer: “You’re running down another rabbit trail. Move on to something else.” At one point when the judge had admonished Haynes to get off some inadmissible harangue, Haynes barked, “If we’re not going to be able to go into that, we might as well not go into anything!” Moore barked back, “Well, we’re not!”

The nearest thing the defense had to a bombshell witness was a secretary who claimed to have seen McCrory, Burleson, and Priscilla together (apparently with one of Priscilla’s lawyers) several months before Cullen’s arrest, but the fact that she had waited five months to tell the story reduced the impact. Later, when another witness claimed to have seen the three together shortly before Cullen’s arrest, Pete Moore very nearly cited the witness for perjury.

However powerful the evidence against his client, Haynes had one undeniable advantage: he didn’t have to prove Cullen’s innocence, just plant the seed of reasonable doubt. Race began scattering seeds like a berserk farmer. He called an ex-convict who testified that McCrory had once offered him $20,000 to kill Cullen Davis. A few weeks later the ex-con was in the Harris County jail, charged with aggravated perjury. Rather than abandon his conspiratorial scenario, Haynes decided to expand it. He called it his “creeper peeper” conspiracy and claimed it included the Tarrant County DA’s office, the FBI, the Texas Rangers, ex-prosecutor Joe Shannon, and finally, Mr. Big himself, Bill Davis, Cullen’s younger brother. Bill Davis had sold his one-third interest in the Davis family empire for $100 million after a long and bitter lawsuit with his two older brothers. Haynes claimed that Bill Davis’ men were bugging the headquarters of Cullen’s defense team and feeding information to the Tarrant County DA. But Haynes never got to question Bill Davis. Investigators for the defense, who had been able to turn up an amazing assortment of witnesses, couldn’t locate Bill Davis during the entire eleven weeks of the trial.

By Christmas, almost all the defense attorneys acknowledged that a straight-out acquittal was a near impossibility. “I think all of us would settle for a hung jury,” Mike Gibson said. They could at least get Cullen out on bond and delay a new trial for months. Maybe a different judge would let them travel with their kit of multiple scenarios. Race hadn’t wanted to put Cullen up, but now he had no choice. It was the only way they could explain the tapes.

Cullen’s testimony was the foundation of the conspiracy theory and it essentially meant that all those days and weeks of challenging the tapes and parading red herrings before the jury went by the wayside. The reason he made the tapes, Cullen said, was to “convince Priscilla’s [hired] killers to come over to my side” and testify against her in the divorce trial. The incriminating tapes were to be the killers’ insurance that Cullen wouldn’t double-cross them. Then Cullen told the jury of a strange telephone call on August 10 from a man who identified himself as FBI agent James Acree. The agent supposedly told Cullen that McCrory and others were involved in a plot to frame him, and advised Davis “to play along.” Haynes didn’t intend to prove that it was really Acree who called, only that Cullen believed it was. Cullen had talked to the real Acree several times the previous winter when the FBI was investigating an extortion letter sent to the home of Karen Master.

Cullen then revealed another twist to the plot, one that would become indispensable. Cullen claimed that McCrory had called a meeting on August 18 because an earlier tape they made didn’t satisfy “Priscilla’s killers.” August 18 was the first meeting taped by the FBI, a meeting in which the two discussed killing various people and Cullen said: “Do the judge, then his wife, and that’d be it.” Cullen had no way of knowing that the FBI had wired McCrory for sound, but he had known something else that until now hardly anyone in the courtroom had even considered. McCrory was also holding a small Norelco tape recorder. And here was the clincher: Cullen claimed that on August 20, when McCrory supposedly handed Cullen an envelope containing the photo of Eidson’s body and the judge’s identification cards, the envelope had contained something entirely different—the cassettes of their previous conversations.

Whatever was in the envelope, Cullen had handed it back to McCrory and asked what he intended to do with the contents. McCrory said he was going to get rid of them, and Cullen replied: “Good. Glad to hear it.” What went unexplained was why Cullen was so glad to get rid of the tapes that were supposedly made to attract Priscilla’s killers. The prosecution never asked that question. Also unexplained was why the FBI didn’t find either the Norelco or the cassettes when they searched McCrory before and after his meetings with Cullen. But Haynes had this covered. Early in the trial, when it didn’t seem important, he had asked FBI agent Ron Jannings about the search of McCrory’s car. Haynes specifically asked if the agent limited his probe to a search for “guns or money” and Jannings replied that this was correct.

There was one final twist, and Haynes played it for all it was worth. The phone number that the bogus Agent Acree had given Cullen, the number that Cullen said he used on at least two occasions to report his conversations with McCrory, in fact, the number he was dialing as the cops closed in on him that morning—Haynes asked his client if he recalled hearing that phone number during the course of this trial. Yes, he had, Cullen replied: it was the number of one of Pat Burleson’s karate school franchises.

Cullen’s whole story sounded incredible. It sounded like Racehorse’s story about the classic defense . . . “I don’t even have a dog!” If Cullen really thought he was obeying Agent Acree’s instructions to “play along” then why hadn’t he yelled for Acree as soon as he was arrested? When Cullen’s friend, attorney Hershel Payne, visited his cell the following morning, why hadn’t Cullen told Payne: “This is all a terrible misunderstanding! Call Agent Acree!”? Early in the trial Haynes had pounded at the theory that Cullen didn’t trust law enforcement people—that’s why he was taking matters into his own hands, wearing a bulletproof vest and making tapes with McCrory. This called up another unanswered contradiction: why had Cullen been so quick to believe the August 10 caller was Acree and why had he followed an FBI agent’s advice? The prosecution barely touched on these points.

The final days of the trial dragged along like a toothache. On one occasion Pete Moore had to physically intervene to prevent a fistfight between Haynes and chief prosecutor Tolly Wilson. The judge had flown combat missions during World War II and again in Korea, and once when an accused killer brandished a knife and attempted to escape, the judge jumped down from the bench and pinned the defendant against the wall. But Pete Moore had never dealt with anything remotely like the Cullen Davis trial. “It’s been the worst experience of my life,” he said. Haynes had tried cases in Moore’s court before, but the judge pointed out: “That was before he developed the technique of asking the same question seven different ways.

There was a strong hint of desperation in Haynes’ style. Maybe he was just stalling, hoping to divide the jury, hoping for a mistrial. Moore thought that was the case and deeply resented it. You could tell that Moore greatly admired Haynes as a lawyer, and when this was over they might still be friends. What seemed lost was the respect—certainly a lawyer was obligated to fight for his client, but Moore gave the impression that he felt this time Race was fighting for his own ego. Lawyers and reporters who had followed Haynes’ career, especially those who had watched the two Cullen Davis trials, thought they saw in Haynes something more than a mere high-priced tireless defender of liberty: was it justice that drove Haynes, or was it his own out-of-control egomaniacal competitiveness? Did Haynes really see a conspiracy in which half of Fort Worth was out to frame Cullen Davis, or did he see the terrible apparition of his own vulnerability? Haynes had been a star in Amarillo, but he hadn’t been a zealot. Now the battlefield was Houston, the place where his character was molded, the home of his absolute gut-level peers. The biggest case of his career, the peak. “Who knows,” one Houston attorney speculated. “Ol’ Race might be fighting just as hard if it was Joe versus Blow. The important thing is winning.” Race may not have agreed. The important thing at the moment was not losing.

It was generally agreed that Race’s closing argument was “remarkable”; most remarkable was the fact that no two people who heard it agreed on what was said. It was as though Haynes were talking two simultaneous, harmonious, completely unrelated, and indecipherable languages. He talked a lot about the sequence of events but he might as well have been describing a road map of Australia. The lawyer had a head cold that was developing into flu, but he talked for two hours, alternately raging and dropping his voice to a pitiful whisper. After a while tears came to his eyes. Tears also came to the eyes of one of the jurors, Mary Carter, a woman of strong opinions and a sense of civic duty. During voir dire Mary Carter told the lawyers that she was a medical secretary between jobs and thought serving on the Cullen Davis jury would be a constructive way to occupy her time. She was an unabashed fan of Haynes and told him he was a “household word” in her family. Mary Carter was elected foreman of the jury.

As the lawyers waited through 44 hours of jury deliberation, Jack Strickland took a solitary walk along the bayou, oblivious to the cold gray drizzle and petrochemical smaze. The jury was hopelessly deadlocked, eight to four for conviction. It was just a matter of time until Pete Moore declared a mistrial. Even though it was sure to be a tie, people were going to say the state had lost. Maybe they had. It occurred to Strickland that maybe it was impossible to convict Cullen of any crime, impossible to find any group of twelve people who could look at Cullen Davis, be apprised of his wealth, status, and family background, be subjected to the charm and expertise of Racehorse Haynes and to the ordeal that enormous wealth could foist on a trial, and still reach a unanimous verdict of guilt. Strickland had taken an oath to uphold the system, but for the moment he surely must have been sick of watching Racehorse Haynes twist and torture the system, sicker still of Haynes’ sanctimonious proclamations. In a speech to the state bar association Haynes referred to himself as “a trustee of liberty.” You had to admire his candor. He was certainly a trustee of Cullen Davis’ liberty. Hugh Russell, one of the lawyers who worked on Cullen’s team in Amarillo, once remarked: “The virtue of being a defense attorney is you don’t have to worry about questions like guilt.”

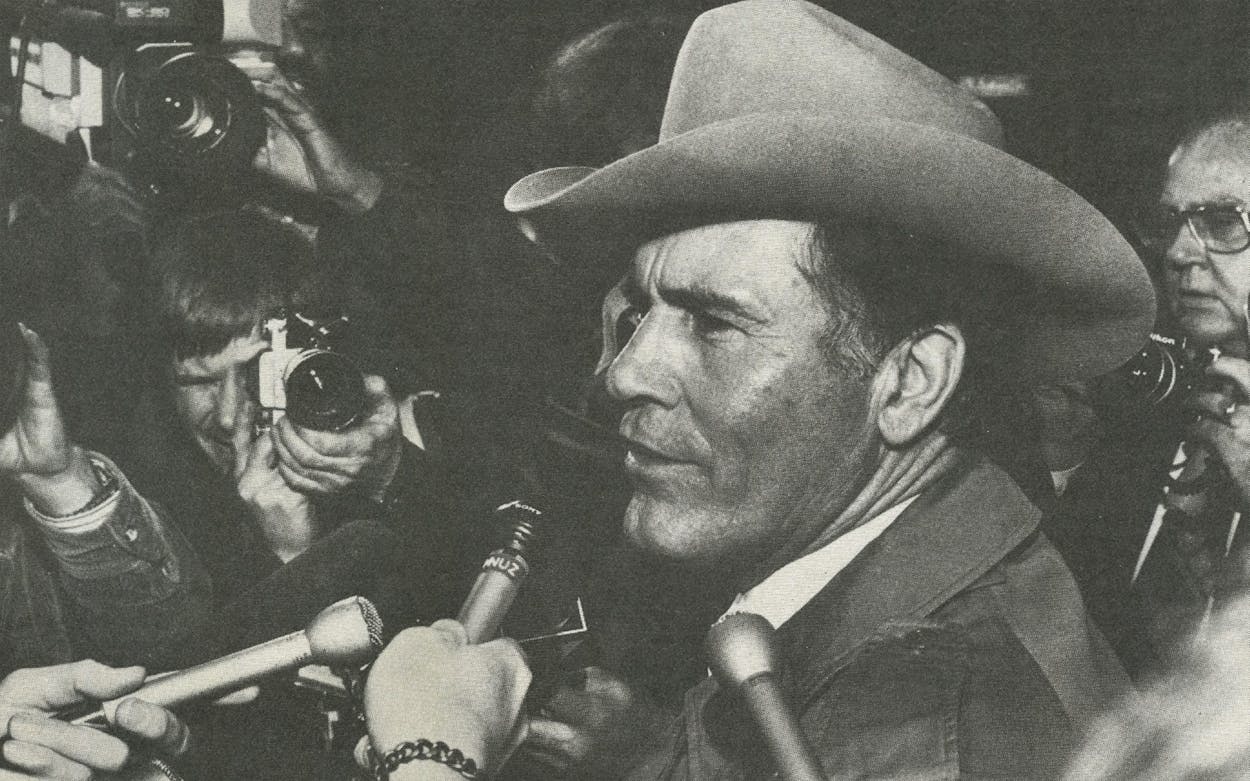

Dozens of reporters clustered around Haynes after the mistrial was declared. Racehorse had dried his eyes but he was trembling like a man who’d just spoken to his own ghost. “They didn’t get us, did they?” he grinned fiercely. When someone brought up the contention that Cullen Davis had bought his freedom, the grin became a scowl of defiance. “Those who say that are bitter, dissident, irresponsible people who have no experience as to how it feels to be poor or wealthy,” Haynes said. “They don’t know that both the very rich and the very poor are vulnerable targets in this country!” At this point in life Race hadn’t made much of a mark defending the poor, but he perhaps intended to. He could afford it. The rumor was that he had jacked up his fee since Amarillo. A million in front and another two million to be paid over a number of years. It was a victory for the system, Race said, a great victory.

Pete Moore disagreed. It was the judge’s opinion that Haynes had just about brought the system to its knees. “The entire system has been abused and I don’t like it,” Moore told reporters. “This trial should have been over weeks ago. After eleven weeks the jurors can barely remember the testimony back in early November.”

Foreman Mary Carter, one of the four who had voted all the way for acquittal, spoke for the minority when she said: “Some of the twelve felt, even with the tapes, the prosecution did not present a strong enough case . . . even if the defense had presented nothing.” Carter was infuriated by the suggestions of several other jurors that she was awestruck by Cullen’s wealth or by Haynes’ charm. “I saw the tapes and heard them,” Mary Carter said firmly, “but I still do not know the reason the tapes were made. Was David McCrory telling the truth when he went to the FBI about Davis wanting people killed? There’s nothing to substantiate his story. Or was Cullen Davis telling the truth when he testified that a representative from the FBI called and told him to play along with McCrory? I believed Davis’ version.”

Another juror, Helen Farmer, freely admitted that she was charmed by Racehorse Haynes. “He has gorgeous eyes,” Mrs. Farmer said. “Do you know how old he is? He really cried during final arguments. I nearly gave him a Kleenex. He’s a wily fox, a really superb lawyer.” Farmer failed to explain, however, why she voted all the way to convict Cullen Davis. How she voted and why was her own business, she smiled.

As soon as Moore announced the mistrial Phil Burleson whipped out a cashier’s check for $30,000 bail, and Cullen was ready to rejoin society. Fifty or sixty reporters waited at the jail entrance as Cullen appeared, pale and smiling. Cullen said he wasn’t bitter, just disgusted with the conspirators. After Amarillo someone asked him what he had learned from his ordeal, and Cullen said he had learned that no matter how rich a man is, it’s not always possible to get bond. What had he learned in Houston? “Not to listen to the FBI,” Cullen said.

A black limousine burned around the corner and stopped abruptly outside the jail entrance. Phil Burleson climbed out and held the door open. Cullen waved one final time, then disappeared into the night.

- More About:

- Longreads