In 1995 a Mount Rushmore of modern blues—Eric Clapton, Robert Cray, Buddy Guy, and Jimmie Vaughan—gathered beneath Austin City Limits’s famous wood-and-cardboard skyline to tape a tribute to Stevie Ray Vaughan. What they played that night was alternately mournful and celebratory. After all, five years earlier the same four men had traded solos onstage with Stevie Ray himself at Wisconsin’s Alpine Valley Music Theatre, mere hours before he died in a helicopter crash. Near the end of the ACL show, Jimmie and his brother’s band, Double Trouble, led the cast—augmented by B. B. King, Dr. John, Art Neville, and Bonnie Raitt—through “Six Strings Down,” a moving gospel-blues fusion he had co-written about Stevie Ray’s passing. “Heaven done called another blues-stringer back home,” they sang.

Nearly two decades later, in late April of this year, Guy and Double Trouble came together for another tribute in the same room, under the same skyline. It too was a celebration—this time, of Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble’s induction into the Austin City Limits Hall of Fame. But it was lost on nobody that this was yet another honor Vaughan wasn’t here to see.

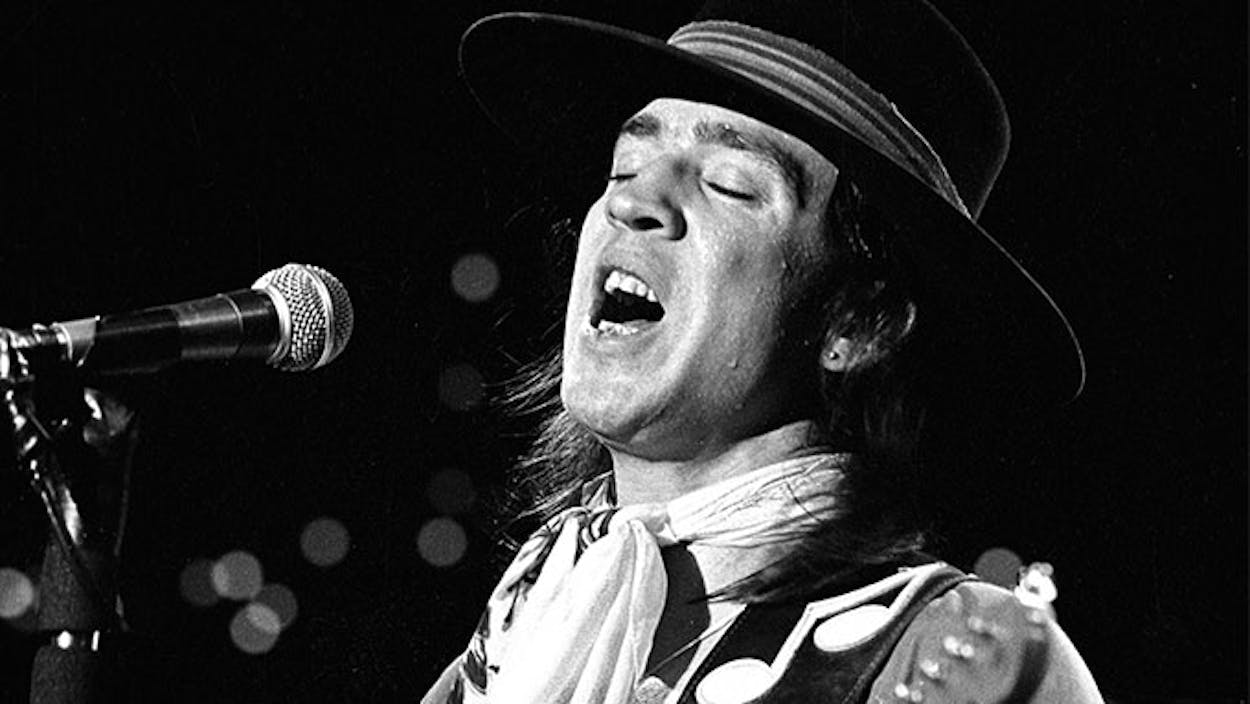

Vaughan and Willie Nelson are the first musicians to be inducted into the ACL Hall of Fame, a new institution, created on the occasion of the PBS show’s fortieth anniversary, that recognizes artists who, executive producer Terry Lickona says, “made [ACL] what it is today.” Vaughan taped two of the show’s defining performances: a 1983 set when he was the hometown kid people suspected might single-handedly revive the blues and a 1989 victory lap after he’d done just that. If he’d lived, he’d surely have made at least a few more appearances, and maybe even inaugurated the program’s new downtown home in 2011.

On this particular spring evening, Matthew McConaughey did the honors as emcee, and Willie and Lyle Lovett led the show-closing, all-cast rendition of “Texas Flood.” It was the Platonic ideal of a night out in Austin—is there a more perfect Texas musical moment than Willie and Lyle singing a Stevie Ray Vaughan song? But you’d be forgiven for thinking that the whole thing felt like the dress rehearsal for something else: Vaughan’s inevitable induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. You can imagine what that night would look like. Clapton would deliver the induction speech and then join Vaughan’s former bandmates, keyboardist Reese Wynans, bassist Tommy Shannon, and drummer Chris Layton, on an incendiary version of “Pride and Joy.” And maybe this time there would be another generation represented—young guns like John Mayer, Derek Trucks, and Gary Clark Jr.

Here’s the thing, though: none of that may be so inevitable after all. Six years ago, Vaughan became eligible for induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (artists become eligible 25 years after the release of their first record). The details of the Hall of Fame nomination process have long been shrouded in secrecy, but a recent story in the New York Times revealed that each September a committee of 35 critics, musicians, and industry representatives meets in the offices of Rolling Stone (magazine co-founder Jann Wenner is also a co-founder of the Hall of Fame) to nominate a dozen or so artists for that year’s ballot. In the years since Vaughan became eligible, more than four dozen groups or artists, including such lesser lights as Bon Jovi and John Mellencamp, have been included on those ballots. Stevie Ray Vaughan, however, has not. Not once.

To get a sense of how shocking this is, take a look at the December 8, 2011, issue of Rolling Stone, in which the magazine compiled its most recent list of the one hundred greatest guitarists of all time. Vaughan ranks twelfth. Every one of the eleven guitar players ahead of him—from Jimi Hendrix to George Harrison to Keith Richards to Eddie Van Halen—are members of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. With the exception of Derek Trucks, who is not yet eligible, Vaughan is the only guitarist in the entire top thirty yet to be inducted. “It’s shockingly peculiar and outrageous,” says ZZ Top’s Billy Gibbons, who was inducted in 2004. “There’s but two questions: A, why not? And B, okay, so when?”

The simple answer to both questions is, nobody knows. The first rule of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame nominating process is you don’t talk about the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame nominating process. (The Hall of Fame did not reply to a request for comment.) We can, though, turn to the Hall of Fame’s eligibility criteria for clues. “We shall consider factors such as an artist’s musical influence on other artists, length and depth of career and the body of work, [and] innovation and superiority in style and technique,” the Hall of Fame’s website explains. “But musical excellence shall be the essential qualification of induction.” Let’s address these one at a time:

Musical influence on other artists. “Within the blues community, I think he’s still the single most influential postmodern guitar player,” says Guitar World editor in chief Brad Tolinski. “He’s much more influential than Eric Clapton or even Jimmy Page, when you listen to young blues players coming up. That world is still full of kids playing SRV shuffles on Strats.” The Austin blues guitarist and Warner Bros. recording artist Gary Clark Jr. agrees. “He changed the way people play Stratocasters. I don’t know of any young guitar player interested in blues who hasn’t studied his licks and wanted to play as powerfully and dynamically as him. I was watching YouTube clips of Stevie just a couple hours ago. I’m still trying to figure it out, and I can’t, which is frustrating. You can’t touch him.”

Length and depth of career and the body of work. Obviously, Vaughan falls a bit short in this regard. But it would be strange to penalize a musician for dying young; many other members of the Hall of Fame—like Hendrix, Janis Joplin, and Kurt Cobain—had similarly abbreviated careers. And in a sense, Vaughan’s career has never ended. Last year, according to Nielsen SoundScan, his combined catalog sold nearly 150,000 albums, numbers that don’t include the digital download of singles or video collections on DVD. Week after week, classic Vaughan albums like Texas Flood and The Sky Is Crying and his Greatest Hits compilation occupy top-ten positions on the “core genre blues chart,” alongside albums from Clapton, Raitt, and B. B. King. In 2013, on the heels of Sony’s release of an expanded two-disc, thirtieth-anniversary edition of Texas Flood, Tolinski put Vaughan on Guitar World’s cover. It was the year’s second-best-selling issue, trailing only a Led Zeppelin cover. “He still sells magazines,” Tolinski says.

Innovation and superiority in style and technique . . . [and] musical excellence. Determining “musical excellence” is a hopelessly subjective exercise, but we can get a pretty solid bead on Vaughan’s status as an innovator and virtuoso. Vaughan was inspired by blues greats like T-Bone Walker, Freddie King, and Albert Collins, but he also idolized Hendrix and, like him, tuned his guitar down a half step, which was crucial to his instantly recognizable tone. Gibbons, who watched Vaughan play clubs in East Austin early in Vaughan’s career, says that his trademark strumming pattern—his right hand would draw an imaginary figure 8 over the strings, almost fanning them instead of plucking, picking, or striking them—was another part of his unique sound. “He was fierce, fast, and there was an X factor of soul and passion,” Gibbons says. “It wasn’t all technique. He mastered the real feel of the blues. A lot of people call attention to his success in interpreting Albert King or Jimi Hendrix. But he didn’t take it note for note. He took the essence of what he loved and expanded upon it.”

In short, Vaughan would seem to be a shoo-in for a Hall of Fame ballot. Actually being inducted, of course, is another issue. Last year Cat Stevens, Hall and Oates, Kiss, Linda Ronstadt, Peter Gabriel, and the E Street Band—acts who began their recording careers in the sixties and seventies—were welcomed into the Hall, long after they should have been, some would say. Exactly why some artists get in the first time they appear on a ballot while others appear on ballots for years before being inducted is a minor mystery. One could make the argument that it’s only fair that Vaughan wait his turn in line to get into the Hall. But his absence from even a single ballot is indefensible; the blues are the rootstock of rock and roll, and nearly a quarter century after his death, Vaughan remains one of the best-selling blues musicians in the world.

So why isn’t he on those ballots?

The answer to that question is a matter of no small conjecture. Vaughan partisans have their theories, which range from the vaguely plausible to the loopily conspiratorial. But some sober observers suggest that Jimmie Vaughan has done his little brother’s legacy no favors with his conservative management of the estate. Jimmie and Sony Music have signed off on relatively few posthumous albums and collections. This failure to promote Stevie Ray to anyone other than loyal blues fans, the argument goes, is one reason he’s made no headway at the Hall of Fame.

Jimmie isn’t having any of it. “The rule is this: if Stevie wanted to put something out, he would have,” he says, adamant that leftover studio scraps won’t be turned into albums and that the albums his brother did release won’t be repeatedly repackaged just to make a buck. “I know him better than anyone. I know that a lot of the songs that he recorded and didn’t release, he didn’t like. It’s that simple. So I don’t sit around and worry about what to put out and not to put out.

“I just haven’t been a whore. Is that conservative?” he asks. “I don’t think so. People yell at me and say nasty things because I won’t go in the studio and finish a couple of songs he didn’t finish. They want me to go and change history. That’s desperate. It’s not what we were about. We weren’t raised that way.”

“At first, I was frustrated,” Chris Layton says of Jimmie’s cautious approach. “But Jimmie has a really tough job. I told him at some point, ‘I stopped arguing with you because he was your family, your brother, another guitar player—all these things I can’t begin to understand.’ Both he and his brother have always had a real sense of what is true to them.”

Actually, the estate may be entering the heaviest period of activity it has seen in a long time. This month, just weeks after the ACL Hall of Fame tribute, the Grammy Museum, in Los Angeles, is putting up a major Stevie Ray Vaughan exhibit—the first solo exhibit for a blues artist in the institution’s five-year history. “Part of our mission as a museum is to make certain the legacies of artists that are no longer with us are remembered, recalled, and celebrated again,” says executive director Bob Santelli, who has no doubts about Vaughan’s importance. “Hopefully this will allow other institutions to pay attention to his legacy—like the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.”

Then there are the reissues. Later this year, Vaughan’s entire catalog is being remixed, remastered, and reissued on 180-gram collector’s vinyl. Next year, 1985’s Soul to Soul is due for an expanded re-release as a two-disc set. So perhaps 2015 will be the year SRV finally gets some love from the folks in Cleveland.

Perhaps. This year Nine Inch Nails, Green Day, and Garth Brooks all become eligible for nomination, and each is a well-connected act. There have always been whispers that the Hall of Fame is as much a celebration of the music industry as it is of artistry—that it’s as much about the businessmen the musicians were connected to as the music they made. Jimmie is the first to suggest that if a higher-profile music industry type had been championing his brother’s case, things might have turned out differently. But he’s torn on whether the Hall of Fame matters at all. At one point, he sneers, “In the real world, it’s sort of a badge of honor not to be in that f—ing thing.” A few minutes later, he says, “I think he belongs in there. And I think it’s important.

“They’re gonna have to do it eventually,” he adds, perhaps trying to convince himself as much as anybody else. “But Stevie’s legacy doesn’t revolve around whether he’s in the Hall of Fame. His legacy is what he did when he was alive.”

That’s fair enough; even if Stevie Ray Vaughan never gets inducted, his music will live on. But it’s hard not to pine a little for one more star-studded run-through of “Six Strings Down,” played mournfully because he’s not here—and in celebration because he’s finally gotten his due.