A few hours before dawn on a sticky summer night in Somerville, a one-stoplight town ninety miles northwest of Houston, police chief Jewel Fisher noticed the faint smell of burning wood. Fisher was following up on a late-night prowler call east of the main drag, in the predominantly black neighborhood that runs alongside the railroad tracks. Turning down the town’s darkened streets, he suddenly caught sight of a house on fire and realized that he was looking at the home of 45-year-old Bobbie Davis, a supervisor at the Brenham State School. Flames climbed the walls and skittered along the roof of the one-story brick structure, casting a murky orange glow. The windows had already been smashed in by several neighbors, who had screamed the names of the children they feared were trapped inside, pleading for them to wake up. Fisher quickly radioed for help, but when volunteer firefighters arrived, they discovered the bodies of Bobbie, her teenage daughter, and her four grandchildren inside. Each person had been brutally attacked and left to die in the blaze.

Word of the killings, which took place on August 18, 1992, traveled quickly through Somerville. The tragedy had no precedent; it was—and eighteen years later remains—the most infamous crime in Burleson County history. “Many in the neighborhood remarked that this was the kind of thing that you expected to happen somewhere else, not in Somerville,” read a front-page article in the Burleson County Citizen-Tribune. Bobbie had been bludgeoned and stabbed. Her sixteen-year-old daughter, Nicole Davis, a popular senior and top athlete at Somerville High School, had been bludgeoned, stabbed, and shot. Bobbie’s grandchildren—nine-year-old Denitra, six-year-old Brittany, five-year-old Lea’Erin, and four-year-old Jason—had been knifed to death. (Bobbie’s daughter Lisa was mother to the oldest and youngest children; Bobbie’s son, Keith, was father to the two middle girls.) All told, the victims had been stabbed 66 times. Even the youngest member of the Davis family, who stood three and a half feet tall, had been shown no mercy. Jason, who investigators would later determine had cowered behind a pillow, was stabbed a dozen times. His body had been doused in gasoline before the house was set on fire.

After daybreak, neighbors gathered to survey the ruins of the Davis home, and TV news crews from Houston came by helicopter, circling overhead. Two Texas Rangers arrived that morning, and two more later joined them, but they had few early leads. There were no obvious suspects and hardly any clues; the fire had ravaged the crime scene, and the killer—or killers—had left behind no witnesses. A night clerk at the Somerville Stop & Shop, Mildred Bracewell, came forward to say that two black men with a gas can had purchased gasoline shortly before the time of the murders. A hypnotist employed by the Department of Public Safety elicited a more precise description from her of one of the men, and a forensic artist sketched a composite drawing of the suspect. Still, there were no arrests.

Four days after the murders, the Rangers got their first break. Five hundred mourners—nearly one third of Somerville—turned out for the funeral, which was held in the local high school gymnasium. Among them was Jason Davis’s absentee father, a 26-year-old prison guard named Robert Carter, whose bizarre appearance that day drew stares. His left hand, neck, and ears were heavily bandaged, as was most of the left side of his face. When Bobbie’s sister-in-law approached him at the cemetery to inquire about his injuries, Carter’s wife, Cookie, quickly answered for him. “His lawn mower exploded on him,” she said. Carter added without explanation, “I was burned with gasoline.” His conversation with his deceased son’s mother, Lisa Davis, was no less strange. Lisa had suffered an unimaginable loss; that day, she would bury two children, as well as her mother, sister, and two nieces. (That her own life had been spared was a quirk of fate; had she not traded shifts with a co-worker at the Brenham State School, she would have been at the Davis home on the night of the murders.) As Carter reached to embrace her, she took a step back, startled by what she saw. “What happened?” she asked, studying his face. Abruptly, Carter turned around and walked away.

After the funeral, the Rangers paid Carter a visit at his home in Brenham, fifteen miles south of Somerville. “I figured y’all would be over here to talk to me because of the bandages,” he told them. The Rangers had learned from Lisa that she had recently filed a paternity suit against Carter, a first step in obtaining child support. Carter had been served with papers just four days before the killings. Ranger Ray Coffman, the case’s lead investigator, read Carter his Miranda rights and asked him to come in for questioning.

That afternoon, at the DPS station in Brenham, Carter sat down with the four veteran Rangers assigned to the case: Coffman, Jim Miller, George Turner, and their supervisor, Earl Pearson. The Rangers were skeptical that one person could have brandished the three weapons used in the murders—a gun, a knife, and a hammer—and had surmised early on that the Davis family had been killed by as many as three assailants. Carter was grilled by the Rangers, but he remained steadfast in his insistence that he knew nothing about the killings. He had burned himself, he told them, while setting fire to some weeds in his yard. By evening, he and the Rangers had reached an impasse, and he agreed to take a polygraph exam. Three of the investigators—Coffman, Miller, and Turner—drove him to Houston, where the test could be administered by a licensed polygraph examiner. He failed it sometime after 11 p.m.

The Rangers continued to interrogate him until well past midnight. After several hours, they wore down Carter’s resistance, and he finally agreed to make a statement about the crime. At 2:53 a.m., Ranger Coffman turned on the tape recorder, and Carter began to talk. He had been present at the Davis home on the night of the murders, he allowed, but it was another man—his wife’s first cousin, Anthony Graves—who was to blame. As he began, he stumbled over the killer’s name, once calling him Kenneth. Later he corrected himself: “I said Kenneth. It wasn’t Kenneth. I’m sorry. Anthony.”

Carter told the Rangers that he had driven Graves to the Davis home after one o’clock in the morning. Graves, he said, had asked him if he knew any women, and the only prospect who had come to Carter’s mind was sixteen-year-old Nicole. He had dropped Graves—who was, by Carter’s own admission, a stranger to the Davis family—off at the front door while he stayed in the car. He did not say exactly how Graves had gotten inside. As he waited for Graves to return, Carter said, he heard someone shouting, and then screams. Alarmed, he let himself in to look around. To his horror, he said, he had walked in on a killing spree. “There was blood everywhere,” Carter said. “He was going from room to room.” Carter maintained that he helplessly looked on while Graves single-handedly murdered the Davis family. “I had no part in it,” he insisted, though he had already accurately described the precise locations where many of the victims had been killed.

Afterward, he said, Graves had retrieved a gas can from the storage room, poured gasoline throughout the house, and set it ablaze, scorching him in the process. Remarkably, he expressed no anger toward the man who, by his own telling, had just murdered his son. After the rampage, he said, he drove Graves back to Brenham and dropped him off at Graves’s sister’s apartment.

During the tape-recorded conversation, the Rangers never stopped to ask Carter fundamental questions that could have determined whether Graves was actually present at the scene of the crime. They never pushed Carter to explain why he would have taken a man who was looking for sex to a house full of sleeping children. Or why Graves would have brutally murdered six people he did not know. They never questioned him about the improbable logistics of the crime he had just described. (How had Graves managed to find a gas can inside the storage room of a house he had never visited?) Nor did they press Carter to admit his own role in the killings. (Wouldn’t Bobbie Davis, whose body was found nearest the front door—where investigators had determined there was no sign of forced entry—have been more likely to let in Carter, the father of her grandchild, than a stranger who had turned up at her house in the middle of the night?) Even after Carter divulged that he had burned his own clothes upon returning home, Ranger Coffman continued to focus on his accomplice, twice prompting Carter to say that he wanted to help investigators find his son’s killer.

Although Carter’s statement was badly flawed, the Rangers had gotten what they wanted: an admission from Carter that he was at the scene of the crime and the name of an accomplice. The possibility that he had falsely named Graves to shift the attention away from himself was never fully explored and would haunt the case during its long and meandering path through the court system over the next eighteen years. “I hope that you don’t use this to lock me up,” Carter said when he was done, his face still partially obscured by bandages.

What evidence the Rangers were able to find later that day pointed exclusively to Carter himself. A cartridge box in his closet held the same type of copper-coated bullets that had been used to kill Nicole. The .22-caliber pistol that he usually kept above his bed was missing. The Pontiac Sunbird that he had admitted driving to the Davis home was gone; he had traded it in at a Houston car dealership two days after the killings. And yet even as his story fell apart, the Rangers continued to pursue their case against Graves. Two warrants were issued hours after Carter made his statement: one for Carter, who was immediately arrested, the other for Graves. There was no physical evidence that tied Graves to the crime and no discernible motive—only the word of the crime’s prime suspect.

Graves, who had moved back to Brenham from Austin that spring after getting laid off from an assembly line job at Dell, was picked up before noon at his mother’s apartment and brought to the Brenham police station in handcuffs. In the station’s booking room, a surveillance camera captured the half hour that passed as the 26-year-old—who was never told why he was being detained—waited, bewildered. He repeatedly asked an officer who busied himself with paperwork what he was being held for, but he was informed that he would have to wait until a magistrate arrived to read him the charges. Graves turned his attention to another officer, who he hoped would be more forthcoming, but the man feigned ignorance. “You don’t know neither?” Graves said, sighing. “I wish somebody would tell me what’s going on.” When the justice of the peace finally appeared, Graves jumped to his feet, eager for information.

“You’re Anthony Charles Graves?” asked the justice of the peace, glancing up from the warrant that she held before her. She was flanked by two police officers.

“Yes, ma’am,” he said.

“Anthony, this is going to be your warning of rights,” she said. Her delivery was matter-of-fact: “You’re charged with the offense of capital murder.”

“Who?” he said, dumbfounded. He stared back at her blankly.

“An affidavit charging you for this offense has been filed in court,” she continued. As she read him his Miranda rights, he watched her in disbelief. “At this time, no bond has been set,” she said. “Do you understand what I’ve told you, Anthony?”

Graves held up his hands in protest. “Capital murder?” he said, incredulous. “Me? Wh-wh-who murdered? I mean—”

A man wearing a white Western hat interrupted him. “You’ll have a chance to talk to the officers who are actually working the case,” he said.

“This is a big mistake,” Graves said, his voice rising. “Capital murder?” Dubious, he turned to the police officer who had brought him down to the station. “This is a joke,” he said, breaking into a grin, as if he were suddenly on to the elaborate prank that he seemed certain was being played on him. “Somebody’s messing with me, right?” The officer, who did not smile back, ordered him to have a seat.

Graves studied the copy of the arrest warrant that the judge had handed to him, trying to make sense of it. He repeated the words “capital murder” eighteen times, enunciating each syllable as if doing so would help him better grasp their meaning. “This is a big mistake,” he repeated. “This has got to be straightened out today.” Finally, before he was led down the hall to talk to the Rangers, he slapped the side of his head and cried out, “Am I dreaming?”

Roy Allen Rueter was listening to the radio at Magnetic Instruments, a Brenham machine shop, when he heard the news that Graves had been charged with six counts of capital murder. Graves had worked for Rueter for three years before moving to Austin to work at Dell, and he had played third base for the company softball team, the Magnetic Instruments Outlaws. Though the two men outwardly had little in common—Rueter, who is white, hailed from a prominent local family; Graves, who is black, was raised in Brenham’s federal housing projects—they had become close friends. After Outlaws games, they would talk late into the night about softball and women, and Graves had counseled the twice-divorced Rueter on matters of the heart. “He could always lift you up out of your own self-indulgent misery,” Rueter said. “He had a big, deep laugh and a lot of charm. Everyone liked Anthony, especially women.” Rueter later proposed to a former classmate of Graves’s, to whom he has been married for the past nineteen years, and he credits Graves, who offered encouragement and counsel during their courtship, for bringing them together. When they got married, Graves was in the wedding party.

The news on the radio deeply affected Rueter. “I knew—everyone who knew Anthony knew—it had to be a mistake,” he said. “I could never imagine him raising his hand to any woman or child, much less doing what he was accused of doing. It was inconceivable.” Rueter called the best lawyer he could think of, Houston defense attorney Dick DeGuerin, and asked him to take on the case. The veteran trial lawyer agreed to represent Graves at his upcoming bond hearing, where the state would have to prove that it had enough evidence to hold Graves. DeGuerin’s expertise did not come cheap; his fee for the hearing and a preliminary investigation was $10,000. Without hesitation, Rueter wrote him a check. “I figured it would take a few days to get straightened out, and then Anthony would come home,” he said. “I kept thinking, ‘Christ, how did Anthony’s name get mixed up in this?’ ”

While Rueter’s father gave his son a job in the family business and bankrolled his favorite diversion—the Outlaws—Graves’s father had been an ephemeral presence in his son’s life. Graves’s childhood in Brenham, the home of Blue Bell Ice Cream, did not unfold in the pastoral small town of the creamery’s television commercials, which are heavy on mom-and-apple-pie nostalgia. He was born to a single mother, Doris Graves, just after her seventeenth birthday and raised in the dreary projects on Parkview Street. His father, Arthur Curry, was a musician and an inveterate womanizer who worked for the Santa Fe Railroad. “He lived with us for a while, and then he’d wander, and then he’d come back,” Doris told me with a shrug. “He was the man of my dreams, the love of my life—blah, blah, blah. That’s the way the story goes.” They married when Graves was two and had four more children together, but Curry’s visits grew more infrequent. In his absence, Graves became the man of the house, making sure that his brothers and sisters did their homework, ate dinner, and went to bed while Doris worked the 2 to 10 p.m. shift at the Brenham State School. Graves succeeded in keeping out of trouble, except when it came to girls. When he was fourteen, he told Doris tearfully that he had gotten a girl pregnant. “He said, ‘Mama, don’t you think it’s time you taught me about the birds and the bees?’ ” she recalled. “And I said, ‘Looks like you’ve already been stung.’ ”

Graves was a handsome kid with a dazzling smile, and he was popular with his peers. The 1980 Brenham High School yearbook, The Brenhamite, features photo after photo of him as a smooth-faced freshman, beaming beside his teammates. He played football and basketball, and he ran track, but it was baseball that he excelled at. His sophomore year, he was devastated to learn that he had been cut from the varsity team to make room for seniors. Rather than be relegated to junior varsity, he moved in with his paternal grandfather in Austin and enrolled in Westlake High School, an elite, virtually all-white school with a championship baseball team.

Former coach Howard Bushong, who led Westlake to state titles in 1980 and 1984, remembered him as a likable kid with a good arm and serious potential. “I was excited to have his caliber of talent in our program,” he said. But Graves’s chance to prove himself—and to perhaps cinch a college scholarship or advance to the minor leagues, as Westlake’s best players often did—was short-lived. His grandfather handed him off to his father, who was living in Austin but who would disappear for days on end, leaving him stranded without food or a way to get to school. Halfway through the semester, his father left for good. Doris picked up her son and brought him back to Brenham.

When Graves returned, he was held back because he had not finished his semester at Westlake. His loose-limbed confidence was gone; rather than throw himself back into baseball, he sat out the next season. He dropped out of school his senior year after another girlfriend informed him that she too was pregnant. Interest from a major league scout, who had approached him about playing in the minors, fizzled once he quit the team. Graves was seventeen, with two children—a three-year-old son and a newborn—to support. He went to work at Blue Bell, loading trucks, and got a job in a factory that made metal clothes hangers. The following year, 1983, his father was shot and killed by a romantic rival in Houston. In the wake of his father’s death, Graves briefly moved to California, where he worked as a security guard. When he returned to Texas, he got into the first real trouble he had ever been in;at 21, he was arrested during a Brenham Against Drugs sweep. After he learned that prosecutors were seeking a fifteen-year sentence, he agreed to plead guilty to selling a small amount of pot and cocaine. He served 120 days in a minimum-security prison in Sugar Land.

After his stint in Sugar Land, Graves put his life in order and went to work as a machine operator at Magnetic Instruments, making oil field equipment. He got along with the other men in the shop, and he helped the Outlaws maintain a winning record on the softball field. During his three years with the company, there was only one incident that had left Rueter shaking his head. One morning, when Graves was working on little sleep, a co-worker swiped two doughnuts that Graves had set aside for breakfast. Graves sucker-punched him, breaking his nose, and when the man lunged for him, Graves ran to his toolbox and pulled a paring knife. A co-worker immediately stepped in and defused the situation. No police report was filed, and neither man lost his job; they were both sent home for a week without pay. Later, though, the confrontation would be used to cast Graves, who had no prior history of violence, as someone who was capable of an act as brutal as the Davis murders.

Graves’s whereabouts at the time of the murders could be confirmed by at least three people, all of whom placed him at his mother’s apartment in Brenham. His 19-year-old brother, Arthur, and his sister Deitrich, who was 21, remembered him coming home shortly before midnight with his girlfriend, Yolanda Mathis. According to Graves’s brother, sister, and girlfriend, it had been a typical night at home. Graves and Mathis had eaten fast food from Jack in the Box and stayed up talking, while Arthur had carried on a marathon phone conversation with a female friend. At about 2 a.m., the couple had lain down on a pallet on the living room floor. (Graves, who was out of work, was staying at the apartment temporarily.) Arthur recalled getting off the phone at about 3 a.m. Before turning in for the night, he had checked to see if the front door was locked. The apartment was cramped, and in order to reach the door, he had needed to step over Graves and Mathis. “Anthony got annoyed,” Arthur told me. “He said, ‘Man, what are you doing? Turn out the light!’ ” By then, the crime—which had gotten under way sometime after 1 a.m., according to Carter’s statement—was done. Somerville’s chief of police had reported the fire at roughly 2:56 a.m.

According to Dick DeGuerin, their story was corroborated by someone he interviewed in the course of his investigation, someone who had no allegiances to Graves: the middle-aged white woman who had been on the other end of the line with Arthur. She and Arthur, a soft-spoken gospel singer who played the organ at New Hope Baptist Church, often talked late into the night, and sometimes he sang her love songs. On the evening of the murders, he had serenaded her with Johnny Mathis standards. When Graves caught him crooning “Misty” into the phone, he had ribbed his little brother mercilessly. The woman, who could overhear Graves mocking his brother in the background, had come to Arthur’s defense, and Arthur had passed the phone so that she could have a word with Graves herself. “She could verify that he had been home when the crime was being committed, but she was reluctant to get involved because she was white,” DeGuerin said. “She was concerned that it would look funny that she had been on a long telephone call with Arthur in the middle of the night. But she did candidly tell me that Arthur had a beautiful voice and that Graves had gotten on the phone while Arthur was singing to her. She said that if she had to testify, she would.” (The woman, who has denied ever speaking to DeGuerin, did not respond to interview requests for this story.)

Ranger Coffman’s 51-page report makes no mention of the white woman—or of Arthur, Deitrich, Mathis, or the Jack in the Box employee who vividly remembered Graves’s visit to the drive-through window, down to the precise details of the order he placed. In fact, little of the report concerns Graves at all; Carter is its focus. So cursory was the Rangers’ investigation into Graves that they never bothered to search his mother’s apartment, where he was arrested. (Some items of clothing and his aunt’s car, which he had been driving, were processed by the DPS crime lab, but nothing was discovered that connected him to the crime scene.) Had the Rangers spoken to more people who knew Graves, they would have learned that while he and Carter had indeed met before, through Cookie, they were not friendly; they traveled in different circles and knew each other only in passing. An introvert, Carter worked the night shift at a prison in Navasota and was considered a bit “off” by people who knew him. He had little in common with the easygoing, gregarious Graves.

When the Rangers questioned Graves after his arrest, they pressed him to tell them about the killings, but Graves insisted that he had no idea what they were talking about. When they told him that “Robert” had fingered him as the killer, he was unable to place his accuser. (Days later Graves would tell a grand jury that if Robert Carter had indeed implicated him in the Davis murders, “he needs psychiatric evaluation.”) He agreed to take a polygraph exam, and like Carter, he was driven to Houston. That evening, Graves—who had not eaten since the previous night and was rattled after more than seven hours in police custody—failed the test. Polygraphs are not admissible in court because of their unreliability, but they can help determine the direction of an investigation. Again the Rangers demanded that he tell them everything he knew about the murders, urging him to give Carter up. Exhausted, Graves broke down in tears, reiterating that he had no knowledge of the crime. When he did not confess to the killings, he was taken to jail.

Three days later, when Carter testified before a grand jury, he recanted the story he had told the Rangers, saying that he had been pressured to name an accomplice. (Exactly what had transpired during the hours leading up to Carter’s tape-recorded statement to the Rangers is unknown; no audio or video recording was made of his interrogation, and the Rangers declined to be interviewed for this article.) “I said ‘Anthony Graves’ off of the top of my head,” he insisted. “They told me they would cut me a deal, that I could walk if I give up a name, if I give up a story, and that’s what I did.” His attempt to clear Graves would have been more credible had he not claimed that he too knew nothing about the crime.

With Carter waffling, the Rangers’ case against Graves rested on Mildred Bracewell, the convenience store clerk who had undergone hypnosis to help the investigation. After Graves’s arrest, Bracewell had picked him out of a photo lineup and a subsequent live lineup. (Her husband, who had also been at the Stop & Shop that night, could not.) Bracewell was never able to identify Carter, and her selection of Graves was problematic; he did not fit her original description or resemble the composite drawing that had been sketched from her hypnotically recalled memories. Bracewell had originally told investigators that the man was tall, with an oblong face, and clean shaven. Graves was five feet seven, moonfaced, and had a mustache.

At the bond hearing that October, more witnesses turned up to bolster the state’s case. Graves had been put in a cell directly opposite Carter’s at the county jail, and a sheriff’s deputy and a jailer took the stand to say that they had separately overheard him admit his guilt to Carter. “Yeah, I did it, and don’t say a thing about it,” the jailer, Shawn Eldridge, remembered him saying. The sheriff’s deputy, Ronnie Beal, recalled, “I heard Mr. Graves state to Mr. Carter that he had done the job for him and to keep his damn mouth shut.” DeGuerin tore apart the witnesses’ credibility, getting Beal to admit that he had not yet met either inmate when he heard them talking through the intercom, casting his identification of their voices into doubt. And Eldridge was forced to acknowledge that on the night in question, he did not write down what he had heard; in fact, he had waited eight days before making a statement to law enforcement officers about Graves’s purported confession, a long time to withhold critical information in a high-profile murder case.

Ranger Coffman told the court that there were other witnesses who had heard Graves’s remarks, but they were not called to testify. Before stepping down from the stand, the Ranger added that he had seen “what appeared to be blood” on a pair of Graves’ shoes, a claim that was not substantiated when the results later came back from the crime lab.

But, DeGuerin warned Graves, no matter how flimsy the evidence against him, the judge was not likely to dismiss such a high-profile case. In the end, Graves—whose arrest had been heralded on the front page of the local newspaper—was denied bond. He would have to remain in the county jail for the next two years, until his case went to trial. After the bond hearing, DeGuerin withdrew as Graves’s attorney. According to Rueter, DeGuerin had informed him that taking the case to trial would run between $150,000 and $200,000, an amount that Rueter had balked at. “Had I known then what I know now, I would have tried to find a way to pay the whole damn thing,” Rueter told me, his eyes watering. “I mean, how do you put a price on a human life?”

The case that the Rangers handed off to the Burleson County district attorney’s office was hardly a slam dunk. “I think in many ways the Graves case was the most difficult case that I tried,” said Charles Sebesta, who served as the district attorney of Burleson and Washington counties for 25 years. “But at the same time, the cupboard wasn’t bare when it came to evidence. We were comfortable with the evidence.” Sebesta—who is lanky and genteel but who enjoyed a reputation during his long tenure as chief prosecutor as a bare-knuckle courtroom adversary—faced enormous pressure, not only to win a conviction against Graves but also to secure a death sentence. Somerville mayor Tanya Roush captured the community’s anger over the killings when she told the Austin American Statesman that some residents did not think putting Graves and Carter on trial was worth the trouble. “They’re saying, ‘Bring back the hangin’ tree, and save the taxpayers’ money,’” she said.

In Graves’s case, the prosecution’s star witness had recanted, and four Rangers had been unable to turn up a plausible motive or any physical evidence that tied Graves to the crime. Still, the district attorney’s office pressed ahead, trying to build a case from the few prospective witnesses it had. Prosecutors also charged another person as an active participant in the Davis murders: Carter’s wife, Cookie. Her indictment stemmed from her unpersuasive testimony before the grand jury, in which she had insisted that Carter had been home with her all evening on the night of the murders. She had also sworn that she had seen no burns on his face when she had left for work the next morning. Investigators had learned that at a health clinic, she had directed a nurse to bandage her husband’s wounds in such a way that he would not look too conspicuous at a funeral they were obligated to attend. Most significantly, Cookie had a bitter rivalry with a member of the Davis family. Both she and Lisa had sons with Carter, born just eight months apart. According to Carter, the paternity suit had capped a tumultuous few years, during which he and Lisa had carried on an affair. Shortly before the murders, Cookie had given him an ultimatum, demanding that he choose between her and Lisa.

Neither the Rangers nor the prosecution seems to have seriously considered the notion that Carter might have named Graves in order to deflect attention from his wife. Nor was another theory fully explored: that Carter, as he would insist after his own trial, was actually telling the truth when he claimed to have had no accomplice. The district attorney had a clear vision of what had happened on the night of August 18, 1992. “There were three weapons, and there were three active participants in the crime: Graves, Cookie, and Carter,” Sebesta told me. “As far as culpability, we know that Graves was the worst one. He had the knife. He was going room to room killing the children. Carter told us that.”

Despite his belief that all three people had executed the crime, the only case that Sebesta could easily make was the one against Carter. The evidence against him—particularly the bullets that tied him to Nicole’s murder—was substantial, and in February 1994 a jury in the Central Texas town of Bastrop, where the trial was moved on a change of venue, found him guilty of capital murder and sentenced him to death. As Graves’s trial date drew near, Sebesta negotiated a deal with Carter’s appellate attorney: If Carter testified against Graves, the state would allow him to plea to a life sentence if his conviction were reversed on appeal. The chances of a reversal were slim, but Carter was inclined to placate the district attorney, given that his wife was under indictment, and he agreed to help the prosecution when Graves went to trial. Even so, Sebesta was not convinced that he would testify. “Our agreement with Carter was extremely tentative,” he said.

The prosecution caught a lucky break that August, one month before jury selection began, when Ranger Coffman and an investigator with the district attorney’s office spotted Rueter shaking hands with Graves at a pretrial hearing. The investigators took Rueter aside to ask him a few questions. Despite a wild goose chase that Carter had led them on, the murder weapons had never been discovered, and they were eager to know if Graves had ever owned a knife. “I told them that I’d given Anthony a souvenir knife, but it was a piece of shit that wouldn’t hardly stay together,” Rueter said. “I’d bought two at the same time and kept one for myself. Mine was so flimsy that I had to keep a rubber band wrapped around it so it would stay shut.” Rueter readily agreed to hand over his knife for testing, certain that nothing would come of it. “I’m around metal all day, and I knew that thing couldn’t kill a rabbit,” he said. “I figured they would test it and that would be the end of that.” Rueter’s switchblade, however, would become a powerful tool in the hands of the prosecution.

“We were going forward with the case even without the knife,” Sebesta told me. “But the knife evidence was a godsend.”

When The State of Texas v. Anthony Charles Graves got under way on October 20, 1994, it was clear that the case would likely be won or lost on Carter’s testimony. But even on the eve of his scheduled court appearance—with opening statements having already been made—prosecutors were not certain that their most important witness would actually take the stand or what he planned to say if he did. Carter’s most recent telling of the murders, which he had recounted to Ranger Coffman weeks earlier, implicated Graves and a shadowy third figure named “Red,” whom he described as “a fellow from Elgin” who had “red hair . . . gold in his mouth, red complexion.” (Carter would later say that Jamaican drug dealers were to blame.) The night before he was scheduled to testify, the prosecution team visited him in the Brazoria County jail, in Angleton, a small town about an hour’s drive south of Houston, where the proceedings had been moved, at the defense’s request, in hope of finding an impartial jury.

At the outset of the meeting, Carter did not regale his visitors with another fantastical story. Instead, he made a simple declaration, one that could have altered Graves’s fate if Carter had waited to announce it on the witness stand the following morning. “I did it all myself, Mr. Sebesta,” he blurted out. “I did it all myself.”

The district attorney was unconvinced. “I gave no credence to it, because it didn’t happen,” Sebesta told me. “Six people were killed. There were multiple stab wounds, and some of the victims were hit over the head with a hammer. One of them was shot five times. We talked about it for a few minutes, and finally I said, ‘I’m tired of this. We’re wasting our time.’ ”

Sebesta quickly shifted the focus of the conversation to Carter’s wife. In fact, it was the subject of Cookie, not Graves, that occupied the rest of the evening. For the next two hours, Sebesta grilled Carter about Cookie and what role she might have played in the killings. As the night wore on and Carter continued to insist on his wife’s innocence, a polygraph examiner was brought in to question him about her involvement. He concluded that Carter showed signs of deception when he answered no to two questions: “Was Cookie with you at the time of the murders?” and “Was Red actually Cookie?” When Carter was informed that he had failed the test, he began to weep.

According to Sebesta, he then confessed that Cookie had taken part in the killings, claiming that she was the one who had wielded the hammer. (Carter added that he had shot Nicole, while Graves stabbed the remaining victims.) Assistant prosecutor Bill Torrey would later write: “This examination, which concluded about 10:30 p.m., was instrumental in ‘breaking’ down Carter’s resistance and facilitating his testimony; testimony which, in post-verdict interviews with jurors, was absolutely essential in their minds, toward corroborating a largely circumstantial case.”

The next morning, as the time neared for Carter to take the stand, he had cold feet. At 7:30 a.m., when the district attorney met with him again, “he basically said that he wasn’t going to testify, period,” Sebesta recalled. “He said, ‘I can’t give her up.’ ” Finally, shortly after 9 a.m., following several reminders from the bailiff that Judge Harold Towslee was waiting for them, Sebesta approached Carter with a deal: If he agreed to take the stand, prosecutors would not ask him about Cookie. Carter at last relented. He would testify against Graves.

Before Carter raised his right hand to be sworn in, Sebesta informed the court of the prosecution’s agreement with the witness: Carter would testify as long as he was not questioned about his wife’s possible involvement in the murders. The district attorney made no mention of the fact that Carter had claimed, less than 24 hours earlier, to have committed the crime by himself, though prosecutors are required by law to hand over any exculpatory evidence to the defense, whether they believe its veracity or not. Sebesta would later claim—when the issue came to light during Graves’s appeals—that he was “ninety-nine percent” certain he had told Graves’s lead attorney, Calvin Garvie, of Carter’s declaration when they bumped into each other in the hallway that morning. Garvie remembers things differently. “He obviously didn’t tell me that,” he explained to me. “That conversation never took place.” Had Sebesta informed him of such a crucial admission, he said, “You can be sure that I would have asked Carter about that on cross-examination.”

Graves, who sat behind the defense table in a borrowed suit, his expression stoic after two years behind bars, was elated to learn that Carter was testifying. “There’s no way this man can sit in front of me and tell a lie like this,” he told Garvie. But when Carter took the stand, he told the jury exactly what prosecutors had hoped for, recounting in a slow, deliberate voice how the two men had gone to the Davis home on the night of the crime. Carter took responsibility for only Nicole’s death; Graves, he testified, had wielded the knife. (He never mentioned who had bludgeoned the victims with a hammer.) In this version of the story, Carter added a new flourish: Graves had taken part in the murders because he was enraged that Bobbie Davis had received a promotion that he felt his mother, who was also a supervisor at the Brenham State School, deserved. And to explain away his grand jury testimony, in which he had declared Graves’s innocence, he stated that he had done so out of fear; one day at the county jail, he said, his and Graves’s cells had both been left open, and Graves had threatened and choked him. Jailers had apparently forgotten to lock the cells that held the two highest-profile murder suspects in the county’s history.

The defense had not been certain until that morning that Carter would testify, and Garvie’s cross-examination was brief and superficial. Garvie, who had never handled a death penalty case before, told me that he was hamstrung by what he and his court-appointed co-counsel, Lydia Clay-Jackson, did not know: They were unaware not only of Carter’s last-minute recantation but also of his statement naming Red as a third assailant, which was not provided to them until later in the trial, when Ranger Coffman took the stand. In addition, the defense attorneys had chosen to pursue an unusual trial strategy: Even though the deal that prosecutors had struck with Carter did not prevent the defense from questioning Carter about his wife, Garvie elected not to. He and Clay-Jackson thought that the indictment against Cookie, like the indictment against Graves, was unfounded, given the lack of evidence against her. They also believed that one of their strongest witnesses was Cookie’s sixteen-year-old daughter, Tremetra Ray, who could tell the jury that Graves had never called the Carter residence shortly before the murders to ask Carter if their plans were “still on,” as Carter had testified. But Tremetra also maintained that her mother was home on the night of the murders. And so Garvie never questioned Carter about the deal he had made with prosecutors, or asked him who had swung the hammer that night, or pressured him to explain what Cookie’s role—if any—might have been.

Before Carter was shackled and transported back to death row, Sebesta posed a seemingly harmless question on redirect examination. “With the exception of the time you went to the grand jury and denied any involvement, all the different stories that you have told have all involved Anthony Graves, have they not?” he asked.

In fact, both the district attorney and his witness knew otherwise; as recently as the previous evening, Carter had said that he had acted alone. But Carter agreed. “They have,” he said.

Sebesta summoned a procession of prosecution witnesses to the stand, but Mildred Bracewell, the hypnotized store clerk, was not among them. Carter had changed his story since making his original statement to the Rangers, testifying that he had purchased gasoline before picking up Graves and driving to Somerville; his new account made Bracewell’s eyewitness identification all but impossible. In her absence, the district attorney focused instead on the “knife evidence.” Rueter’s switchblade—state exhibit #192—was shown to the jury, and Rueter was called to testify that he had given Graves a virtually identical knife. Travis County medical examiner Robert Bayardo, who delivered a detailed account of the victims’ stab wounds, stated that the blade, or a knife just like it, could have been the murder weapon. Yet under cross-examination, he also conceded that its dimensions were “very common.” To buttress his testimony, Sebesta called Ranger Coffman to the stand. With his resolute gaze, the lawman was the picture of unimpeachable authority. As he held state exhibit #192 in his hands, it was easy to forget that Rueter’s switchblade was not the actual murder weapon but a stand-in with no connection to the crime.

The Ranger described how, on a visit to the medical examiner’s office, he had observed Bayardo insert the switchblade into puncture wounds found on two of the victims’ skulls. (A forensics expert would later conclude during Graves’s appeals that Bayardo’s techniques were not only unscientific and inaccurate but also likely damaging to the evidence—a claim that the former medical examiner denies. “The knife went in and out without any force, without damaging the bone,” he told me.) When the coroner slid the knife into the skulls, the Ranger told the jury, “it fit like a glove.”

The two original witnesses from the jail—Ronnie Beal and Shawn Eldridge—were called to testify, as were two more men: inmate John Bullard, who had been arrested for forgery, and a local rancher named John Robertson. Bullard claimed to have heard Graves ask Carter, “Did you tell them everything?” and observed the two inmates using hand signals after they realized that the intercom was on. (Bullard also admitted that he had been on three different psychotropic medications at the time.) Robertson, who told the jury that he had stopped by the jail to drop off dinner for a friend, stated that he had overheard Graves say, “We f—ed up big-time,” and assure Carter that any incriminating evidence had been disposed of. Like Beal and Eldridge, he professed to have listened to the two men over the jail intercom. But in aggressive cross-examination of all four men, Clay-Jackson was able to establish that the intercom worked only intermittently and that the jail, which was not air-conditioned, had been noisy that August night, with a fan whirring and a TV blaring in the background. She scored her best point of the trial when she had Eldridge, the jailer, look over his log from the night in question, which included detailed notations (“Served supper”; “Med. to Bullard”) but no mention of Graves’s supposed confession.

After the state rested, the defense called Robert Bux, the deputy chief medical examiner for Bexar County, who testified that the fatal injuries could have been caused by “any single-edged knife.” Wanda Lattimore, a supervisor at the Brenham State School, disproved the motive that Carter had provided for Graves when she told the jury that Graves’s mother had never expressed any interest in the position to which Bobbie Davis had been promoted. But the defense’s best effort to establish Graves’s innocence—proving that he was home at the time of the crime—fell short, handicapped by the fact that the white woman whom Arthur had sung to on the phone refused to testify. (“She cried and told me that her parents would disown her if they ever knew about her relationship with me,” Arthur said, still thunderstruck at the memory.) Arthur told the jury in no uncertain terms that his brother had been at home that night, but his sister Deitrich was never called to corroborate his testimony. That task fell to Graves’s girlfriend, Yolanda Mathis. Shortly before Mathis took the stand, while jurors were outside the courtroom, Sebesta sprang a trap.

“Judge, when they call Yolanda Mathis, we would ask, outside the presence of the jury, that the court warn her of her rights,” the district attorney announced. “She is a suspect in these murders, and it is quite possible, at some point in the future, she might be indicted.”

Never before, in the more than two years that had passed since the killings, had Mathis been identified as a suspect. (When I pressed Sebesta about this, he said, “There was some thought that she could’ve been a fourth person in the vehicle,” although nothing in the Ranger reports or the trial record supports such a charge. In hindsight, he added, “I don’t think she was involved.”) Garvie could have requested that Judge Towslee stop the proceedings and hold a hearing, at which point Sebesta would have been obligated to show the court what proof he had to substantiate his claim. But Garvie never called his bluff. (“I thought he would fight for my son because he was of color too,” said Doris, who had retained Garvie by cashing in her life savings. “But he let Sebesta intimidate him.”) Ethically, Garvie told me, he felt bound to warn Mathis, who had no attorney, that she had been named as a possible suspect. When he and Clay-Jackson informed her that she could face indictment for the murders, she became hysterical. Terrified, she refused to testify.

Mathis’s absence left a gaping hole in the defense’s case that went unexplained to the jury. Making matters worse, the witness whom Graves’s attorneys had pinned their hopes on, Tremetra Ray, strained credulity when she testified that both her mother and stepfather, Robert Carter, had been home all evening on the night of the murders. Before the state rested at the close of the five-day trial, Sebesta underscored the fact that the switchblade Rueter had given Graves was never recovered, emphasizing that Graves had denied owning a knife when he had testified before the grand jury. “We have a co-defendant who has placed Anthony Graves at the scene,” Sebesta told the jury. “He has placed a knife in his hand.” In the end, though jurors knew about Carter’s deal with prosecutors, they chose to believe his account of the night of August 18, 1992. After more than twelve hours of deliberation, they found Graves guilty of capital murder.

“Five children and a grandmother had been brutally murdered, and because of that, I think the burden on the state to prove its case beyond a reasonable doubt was somewhat less than it should have been,” Garvie told me. During the trial’s emotional penalty phase, a death sentence seemed all but a foregone conclusion. After Graves’s workplace fight was offered as proof of his propensity for violence, the jury listened as the anguished members of the Davis family cataloged their grief. “There are some crimes that are so violent, that are so horrendous, that there is but one decision that you as a jury can make,” Sebesta advised jurors at the conclusion of his closing argument. “Pick up the photographs of those six people and you’ll know what to do.” The jury—whose foreman was the panel’s lone black member—took less than two hours to assess a punishment. Anthony Graves was sentenced to death.

Four years later, on January 14, 1998, Carter penned a remarkable letter to his high school English teacher, Marilyn Adkinson, and her husband, Howard, a pastor, both of whom had visited him on death row. “I’m not sure how to begin this letter, but with God’s help, of course, ‘I can do all things’ (Phil. 4:13),” wrote Carter, who had undergone a dramatic jailhouse conversion since Graves’s trial. In careful handwriting that filled three pages, he confessed to the Adkinsons that he had falsely testified against Graves to protect his wife—“she is totally innocent”—and, by extension, their son, Ryan. “The D.A. and law enforcement believe she was involved, so I lied on an innocent man to keep my family safe,” he wrote. “I even told the D.A. this before I testify against Graves, but he didn’t want to hear it.”

Both Carter and Graves had been sent to the Ellis Unit, in Huntsville, where they separately lived out their days amid the more than four hundred condemned men awaiting their execution dates. After their convictions, charges against Cookie were dropped due to a lack of evidence. During his time on death row, Graves maintained a near-spotless disciplinary record. (He was cited once for possessing what was deemed to be contraband: some green peppers that he had swiped from the food cart.) Carter, meanwhile, diligently read the Bible, making detailed notations in the margins. As his execution date approached, he spoke of Graves’s innocence to more than half a dozen people, including his appellate attorneys and at least two death row inmates: Alvin Kelly, who was executed in 2008, and Kerry Max Cook, who had been sentenced to death for the 1977 murder of a Tyler woman. (During his fourth trial, in 1999, Cook pleaded no contest in exchange for his freedom. DNA evidence later showed that semen at the crime scene belonged to another man.) Of hearing Carter’s confession, Cook would write in his memoir, “As I looked deeply into the face of Robert Carter, I knew—just as I knew my own innocence—I had witnessed the truth.”

Carter also penned letters to the Davis family, declaring that Graves had no knowledge of the crime. To Lisa, he wrote, “I just don’t want [an] innocent person to die for something they don’t know anything about.” To Kenneth Porter, the father of Lisa’s other murdered child (the “Kenneth” he would later suggest had been on his mind when he gave his initial statement to the Rangers), he wrote, “I am the only one responsible . . . I also know that I have lied in the past about this and I can certainly understand you and the rest for not wanting to believe me now.” Hopeful that he could correct the record, he reached out to Graves’s state habeas counsel, Patrick McCann. “He asked me to come to Huntsville because he had important information to tell me,” McCann said.

Carter had contacted McCann at a critically important time in Graves’s appeals. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals had reviewed his case, and in 1997 it upheld his conviction. The court—which in the late nineties overturned 3 percent of capital convictions, the lowest reversal rate of any state in the nation—had rejected the argument that there was insufficient evidence at trial to corroborate Carter’s testimony. McCann had been appointed to handle the next phase of Graves’s appeals: filing a state writ of habeas corpus. In the long and byzantine path that a case follows through the courts after a defendant is handed a death sentence, the writ ushers in the most important stage, in which new and exculpatory evidence can be introduced. But the time frame when such evidence may be brought before the court is finite; in Texas, death row inmates are usually limited to a single state habeas appeal—and only during this habeas phase may new facts be introduced. McCann hurried to Huntsville to meet with Carter, who he hoped would admit that his testimony at Graves’s trial had been perjured. As a court reporter took notes, Carter gave McCann a deposition in which he claimed sole responsibility for the crime.

There was just one problem: Carter’s attorney, Bill Whitehurst, had already barred McCann from speaking to his client. “We could not have our client going out and giving depositions, talking about how guilty he was, at the same time that we were presenting a federal writ of habeas corpus, trying to get him a new trial,” Whitehurst explained. “It was obvious that McCann believed in his client’s innocence and wanted to do everything he could to help him, and I respect that. But I also had an obligation to my client, which I took very seriously.” In going around Whitehurst, McCann—who was less than three years out of law school—had also failed to notify the district attorney’s office of his plans to take a deposition from Carter. It was a fatal error: Because he had deprived prosecutors of the chance to cross-examine Carter, the deposition was rendered inadmissible. McCann’s only remaining opportunity to get Carter on the record was to subpoena him to appear at a 1998 evidentiary hearing that Judge Towslee had granted on several issues raised in the writ. But Whitehurst, a past president of the State Bar, warned the young lawyer that Carter would plead the Fifth if he were subpoenaed. Rather than risk his case on a notoriously unreliable witness, McCann did not call him. The court would never hear Carter’s recantations.

Thirteen days before Carter’s execution, in the spring of 2000, after all of his appeals had been exhausted, Graves’s counsel was granted the opportunity to question Carter under oath. Attending the death row deposition were Sebesta and Graves’s new appellate lawyers: veteran capital defender Roy Greenwood and former state district judge Jay Burnett. (McCann, a Navy reservist, had been called to active duty in Bosnia.) As he sat before the assembled attorneys in his starched prison whites, Carter stated in a low, flat voice that he alone had murdered the Davis family. Without betraying any emotion, he said that he had set out for Somerville on the night of August 18, 1992, with the intention of killing his son. He did not attempt to justify himself or explain whether or not he had anticipated that five other people would be present at the Davis home that night. (Nicole, Brittany, and Lea’Erin had returned the previous day after spending the summer in Houston.) Yet he did describe in specific and chilling detail how he had carried out the crime. First, he said, he had stabbed Bobbie to death after knocking her unconscious with a hammer. As for how he had overpowered the remaining victims single-handedly, Carter was nonchalant. “They were asleep,” he said.

Under cross-examination from Sebesta, Carter grew animated, pushing back as the district attorney once again questioned him about Cookie. “I told you personally, just like I told Ranger Coffman that day when you came to that jail,” Carter said. “I told you, just like I told my brother, ‘It was all me,’ but you said you didn’t want to hear it.”

“We said we wanted the truth, didn’t we, Robert?” asked Sebesta. “Isn’t that what we told you? ‘We want the truth’?”

“I’m talking about the day at the jail,” Carter countered. “You said that you didn’t want to hear that coming out of me.”

“I don’t recall that,” Sebesta said.

On May 31, 2000, the day that Carter was set to die, his family gathered in Huntsville. He read the Bible, visited with his mother, and ate his final meal: a double cheeseburger and fries. At 6:02 p.m., he was led to the execution chamber, where he was strapped to the gurney. After two IVs were inserted into his arms, the warden asked if he had any last words. “I’m sorry for all the pain I’ve caused your family,” Carter said, turning toward the six grieving relatives of Bobbie Davis who had gathered as witnesses. “It was me and me alone. Anthony Graves had nothing to do with it. I lied on him in court.” Carter looked to his own family, who stood on the other side of the execution chamber, behind Plexiglas, but Cookie was not there. She had become distraught that morning and returned to Brenham. “I am ready to go home and be with my Lord,” Carter said, shutting his eyes. As the lethal dose of chemicals flowed into his veins, he coughed, then uttered a soft groan. He was pronounced dead at 6:20 p.m.

Death row inmates who maintain that they have been wrongly convicted are at the mercy of not only the judiciary—where capital appeals typically take more than a decade to move through both the state and federal courts—but also of reporters, law professors, journalism professors, and student volunteers, who may or may not choose to look into their claims of innocence. Often an inmate’s last hope is to capture the attention of an organization like the University of Houston Law Center’s Texas Innocence Network, an ad hoc organization of professors and law students that researches such claims. (Court-appointed appellate attorneys who lack the resources to fully investigate capital cases are usually grateful for the help.) The Innocence Network—which works in conjunction with the journalism department at Houston’s University of St. Thomas—first learned about Graves from his attorneys; David Dow, the network’s director, suggested to a journalism professor at St. Thomas named Nicole Cásarez that her students look into the case.

“We started with nothing,” remembered Cásarez, a former Vinson & Elkins associate with short brown hair and a concerned, precise manner. “Four or five students and I drove to Austin in the fall of 2002, and we read the trial transcript, sitting around Roy Greenwood’s dining room table, taking handwritten notes. From there, we asked ourselves, ‘Who do we need to talk to?’ ” She and her students next traveled to Brenham, where they met two of Graves’s alibi witnesses, Arthur and Deitrich Curry. Cásarez and her students found the siblings to be credible, but it was their interview with Yolanda Mathis that left a profound impression. “Yolanda confirmed that she had been with Anthony all night, but she also explained that they had not been in a big, serious relationship,” Cásarez said. “She had been one of many women in Anthony’s life. That was important, because she did not have the motivation that a brother or sister might have to cover for him. She told us, ‘Why would I still say I was with him that night if it weren’t true? I’m married. I’m a mother. Why would I want to protect a child murderer?’ ” The conversation was a turning point for Cásarez. “Until then, all we knew was that Yolanda had been called and didn’t testify,” she said. “Hearing her story, seeing how thin the evidence had been at trial, I began to feel very uncomfortable with this case.”

At the time, Graves’s prospects looked bleak. In 2000 the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals had denied his writ of habeas corpus—in essence, concluding that he had received a fair trial. Afterward, his lawyers filed a motion asking the court to grant him another habeas appeal, arguing that he should be granted such an opportunity because his first habeas attorney had been incompetent. (McCann’s failure to subpoena Carter, they reasoned, was proof of ineffective assistance of counsel.) The court agreed to consider the claim, but in January 2002, a 6—3 majority ruled against Graves once again. Writing for the majority, Judge Cathy Cochran stated that a defendant was guaranteed the right to a qualified court-appointed attorney but not necessarily to one who performed well. Judge Tom Price penned a stinging dissent, noting that it was the Court of Criminal Appeals that had appointed McCann to Graves’s case in the first place. “ ‘Competent counsel’ ought to require more than a human being with a law license and a pulse,” he observed. With that, Graves’ state appeals were done. His last resort would be the federal courts, which would not be able to take into account Carter’s recantations. “If it wasn’t in the state record, the federal court couldn’t consider it,” Cásarez explained.

But if his federal appeals were successful, there was always the chance—however unlikely—that he would be granted a retrial, in which any new or exculpatory evidence that had been discovered would likely be admissible. So Cásarez and her students forged ahead, interviewing upward of one hundred people over the next few years. “We got in touch with anyone who might know anything about the case,” Cásarez said. They tried, fruitlessly, to convince the white woman whom Arthur had serenaded on the night of the murders to speak with them, but she refused. “She had denied knowing Arthur, so I made Xerox copies of cards she had sent him and a note she had written on the back of one of her deposit slips and forwarded them to her,” Cásarez said. “A man’s life was on the line.”

They succeeded in getting Carter’s older brother, Hezekiah, who had dodged them several times before, to finally agree to an interview when they visited him at his house in Clay, near Somerville. Hezekiah explained that he had traveled all the way to Angleton—a nearly three-hour drive—on the eve of his brother’s testimony in Graves’s trial at the behest of the district attorney, who had arranged to pay for his expenses and a hotel room. “Mr. Sebesta told me that Robert was having reservations about testifying,” he wrote in a sworn affidavit. “I agreed to come down to Angleton and talk to Robert.” Hezekiah stated that before taking the stand, his brother had been “troubled, uncomfortable and scared.”

Cásarez’s students also met with John Bullard, the heavily medicated jailhouse snitch, who, they learned, was under the mistaken impression that his testimony had helped Graves. Bullard, whose cell had been near Graves’s, explained that he had only heard the man proclaim his innocence. Cásarez interviewed jailer Wayne Meads, who had been on duty at the county jail on the same night that Beal, Eldridge, and Robertson claimed to have overheard Graves admit to taking part in the killings. Meads told Cásarez that he had overheard nothing unusual on the intercom that night. “If I had heard either Carter or Graves confess, it would be something I would never forget,” he said. Casting more doubt on the reliability of the jailhouse testimony was a revelation about Robertson. Acting on a tip, one of Cásarez’s students, Sarah Clarke Menendez (who would later go on to graduate from Harvard Law School), sifted through records at the Burleson County courthouse and found that Robertson had been under indictment at the time that he reported Graves’s alleged statements to investigators. The charges against him, for cruelty to horses, were never pursued.

One of the most revelatory moments in Cásarez’s investigation came when she visited Marilyn Adkinson, Carter’s high school English teacher. Adkinson had never observed any signs of trouble in Carter when he was younger, she told Cásarez—in fact, he had no criminal record before the killings—but she mentioned something that she had found curious. Carter had held on to a book that she had assigned his class years before, Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy. He had never gotten around to reading it until he was on death row. When he finished it, Adkinson explained to Cásarez, he had told her, “This is my life.”

The novel, which served as the inspiration for the 1951 film A Place in the Sun, tells the story of a young man from humble origins who is torn between two women: a wealthy woman, whom he hopes to wed, and a poor woman, with whom he shares a secret relationship. The poor woman gets pregnant and threatens to reveal their affair unless he marries her. Afterward, he takes her on a boat ride, and when their rowboat capsizes, he hangs back as she struggles to keep her head above water. Ignoring her pleas for help, he watches her drown. The parallels to Carter’s life were not exact—neither woman in his life was wealthy by any measure—but the story gave Cásarez insight into the psyche of a man who had, by his own admission, felt enough rage to kill his own illegitimate child.

At the conclusion of An American Tragedy, the protagonist is caught, arrested, tried, and sentenced to death. Before he is executed, he becomes a Christian. “Marilyn told me that Robert really identified with this character,” said Cásarez. “He told her, ‘If I had read this book in high school, maybe all of this would never have happened.’ ”

From the viewpoint of the federal courts, the most important development in Graves’s case would turn out to be a casual remark that Sebesta himself made to a television producer after Carter’s execution. In 2000, during George W. Bush’s first run for the White House, Geraldo Rivera came to Texas to make an hour-long NBC special, Deadly Justice, about capital punishment. Although Graves’s case had received scant media attention in the eight years since his arrest, the show’s producers interviewed him at the urging of Kerry Max Cook, whose own case was highlighted in the documentary. Sebesta agreed to talk to producers as well. While the cameras were rolling, the district attorney admitted—for the first time—that Carter had told him, before taking the stand at Graves’s trial, that he had acted alone. “He did tell us that,” Sebesta said. “ ‘Oh, I did it myself. I did it.’ He did tell us that.”

The documentary, which painted Graves’s case in broad strokes, did not seize upon the singular importance of the district attorney’s admission. “If Sebesta had not said what he said, there’s a fair chance that Anthony would have been executed by now,” Greenwood told me. “His statement allowed us to raise a Brady claim for the first time, and that was the only winner we had.” Brady v. Maryland, a landmark 1963 Supreme Court ruling, requires prosecutors to turn over any exculpatory evidence to the defense. Failing to do so is a “Brady violation,” or a breach of a defendant’s constitutional rights—a claim that Greenwood could raise before the federal courts.

“This was the ultimate in Brady material,” Greenwood said. “It was a one-witness case, and the witness recanted! And it was not divulged to the defense.” That fact—that in the midst of Graves’s trial, Carter had told the district attorney that he had acted alone—did not come to the attention of Graves’s lawyers until the deposition Carter gave shortly before his death. “Having Carter say it didn’t matter,” explained Cásarez. “What mattered was having Sebesta admit it, which he did, on camera. Otherwise, it would have just been Carter’s word against Sebesta’s.”

Even with such a powerful argument in hand, it would take several years before Graves’s claim was considered by a federal court in any substantive way. The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals began reviewing his case in 2003 after a lower court had denied relief, and the following year, it granted an evidentiary hearing. At issue was Carter’s statement to Sebesta that he had acted alone, as well as a second comment that the district attorney claimed Carter had made on the eve of his testimony at Graves’s trial: “Yes, Cookie was there; yes, Cookie had the hammer.” (Sebesta did not mention this until 1998, during a hearing in Graves’s first habeas appeal; Carter consistently denied ever implicating his wife in the crime.) The evidentiary hearing, which took place in federal district court in Galveston, included testimony from Sebesta and Graves’s two trial lawyers. U.S. magistrate judge John Froeschner, who presided over the hearing, found as fact that Sebesta did not reveal to the defense Carter’s statement that he committed the murders alone. But he denied Graves’s Brady claim, saying that Carter’s comments would not have altered the outcome of the trial; a jury, he reasoned, would still have decided to convict him. U.S. district judge Samuel Kent delivered a ruling that upheld Judge Froeschner’s findings the following year.

Dispirited, Greenwood asked Cásarez if she would begin drafting Graves’s clemency petition to the Board of Pardons and Paroles. (In 2005 Cásarez reactivated her law license so that she could join Graves’s legal team.) “It was the end of the road,” Cásarez said. “The Supreme Court was not going to take the case. If Anthony didn’t get his conviction reversed by the Fifth Circuit, it was done, dead, over.”

Greenwood appealed the decision to the Fifth Circuit, and on March 3, 2006, a three-judge panel handed down a stunning rebuke to the lower courts. In a unanimous opinion, the panel held that the state’s case had hinged on Carter’s perjured testimony. Had Graves’s attorneys known of Carter’s statements to the district attorney, wrote circuit judge W. Eugene Davis, “the defense’s approach could have been much different . . . and probably highly effective.” The court reserved particular criticism for Sebesta for having prompted two witnesses to say on the stand that Carter had never wavered, other than in his grand jury testimony, in identifying Graves as the killer. (Sebesta had done this not only with Carter but with Ranger Coffman as well.) Wrote Davis, “Perhaps even more egregious than District Attorney Sebesta’s failure to disclose Carter’s most recent statement is his deliberate trial tactic of eliciting testimony from Carter and the chief investigating officer, Ranger Coffman, that the D.A. knew was false.”

With the stroke of a pen, Graves’s conviction was overturned. The ruling did not make any determination as to his actual innocence or guilt. But by finding that his conviction had been improperly obtained, the court paved the way for a new trial.

Students began arriving in Cásarez’s office late that afternoon. “We read the opinion out loud, and we were cheering,” she said. “We were so relieved that finally someone saw the case the way we did.” Amid the jubilation, she and her students puzzled over how to convey the news to Graves. “Death row inmates can’t get phone calls, but I knew that he sometimes listened to The Prison Show,” Cásarez said. “So we called KPFT, and I explained what had happened, and they agreed to call me at eight o’clock that night and give me one or two minutes on the air. My students and I wrote a short statement. I had to practice reading it without crying, because every time I read it, I would start crying. Anthony wasn’t listening to The Prison Show that night, but someone else on death row heard the show and gave a note to one of the guards to take to him. The note said, ‘Hey bro, just heard your conviction’s been overturned. Congratulations. Guess you’ll be getting out of here at last.’”

On September 6, 2006, Graves walked off of death row. But there was no celebration beyond the floodlights and the coils of concertina wire, no crush of television reporters shouting questions, no tearful embrace with his mother, whom he had been allowed to touch just once during his fourteen years of incarceration. Instead, Graves walked out of his six-by-ten-foot concrete cell and into the arms of Burleson County sheriff’s deputies, who transported him back to the county jail in Caldwell, where he would await retrial. The Fifth Circuit’s ruling had not exonerated him, and he still faced the original criminal charges that had been filed against him in 1992. In the eyes of Burleson County, he remained a murderer, and a child killer at that. Judge Towslee’s successor—his daughter, Judge Reva Towslee-Corbett—set his bail at $1 million.

The Burleson County district attorney’s office, which Sebesta left in 2000, could have dismissed the charges against Graves. A federal court had thoroughly discredited the testimony that had put him on death row, and the man who had admitted to the killings had already been executed. Still, many people—most notably the surviving members of the Davis family—believed in Graves’s guilt and were not persuaded by Carter’s eleventh-hour recantations. Days after Graves’s conviction was overturned, Bobbie Davis’s niece, Anitra Davis, told the Houston Chronicle, “We are still waiting for justice.” The county moved forward with plans to retry Graves, and in early 2007 it appointed former Navarro County district attorney Patrick Batchelor as special prosecutor. (The Burleson County district attorney’s office recused itself from the case after Judge Towslee-Corbett ruled that an assistant district attorney, who had helped prosecute Graves thirteen years earlier, could not take part in the new trial.) A skilled adversary, Batchelor had previously won the capital conviction of a Corsicana man accused of a 1991 triple murder, Cameron Todd Willingham, who later became the subject of national debate when updated forensic science called his 2004 execution into question.

In February 2007 Batchelor announced that he would be seeking the death penalty against Graves. The defense suffered another setback that July, when Judge Towslee-Corbett handed down a startling decision: Carter’s original trial testimony would be admissible at Graves’s retrial. The judge reasoned that Graves’s constitutional right to “confront the witness”—that is, to question or challenge his accuser—had already been satisfied when Carter was subject to cross-examination in 1994. Attorneys with the Lubbock-based Innocence Project of Texas, which had taken on Graves’s case pro bono after Greenwood retired, filed a motion with the trial court arguing that any retrial in which Carter’s testimony could be read to a jury would simply be a replay of Graves’s original, flawed trial, a situation that amounted to double jeopardy. Judge Towslee-Corbett denied the claim, as did the Tenth Court of Appeals, in Waco, where the attorneys appealed her decision. Last year, the Court of Criminal Appeals declined to take up the case, allowing Judge Towslee-Corbett’s ruling to stand.

Graves’s retrial is now set to begin in February. As if his path through the legal system had not been protracted enough, the retrial has been beset by delays, including months in which parts of the victims’ skulls and other key exhibits have gone missing. (The evidence was later discovered in an old jail cell that had been welded shut.) Batchelor, who stepped down from the case for health reasons in late 2009, has been replaced by special prosecutor Kelly Siegler, a former Harris County assistant district attorney who has sent no fewer than nineteen defendants to death row. Siegler, who declined to comment on this case before trial, is known for her flamboyance and ability to make the horror of a crime viscerally real for a jury. She once famously re-created a murder by pretending to stab another attorney with the actual murder weapon while straddling him on a blood-stained mattress.

Representing Graves will be veteran capital defender Katherine Scardino and her co-counsel, Jimmy Phillips Jr. Assisting the trial lawyers as third chair will be Cásarez, who can quote the trial record from memory. In 1997 Scardino won the first acquittal for a Harris County capital murder defendant in 23 years. She still does not know whether Judge Towslee-Corbett, in admitting Carter’s testimony into evidence, will also allow in his letters, statements, and deposition recanting his accusations against Graves. “It would be an injustice if Robert Carter’s last statement is not heard by this jury,” Scardino told me. “Even the strongest disbeliever has to stop and take note that he proclaimed Anthony’s innocence from the gurney.”

Meanwhile, the former district attorney remains as convinced of Graves’s guilt as he was sixteen years ago, at his trial. Sebesta believes that Carter’s change of heart was nothing more than a last-ditch effort to protect his wife. “I think Carter was afraid that Graves would make a deal with us after he was executed and give up Cookie in exchange for a life sentence,” he said.

As we sat and talked one afternoon in Caldwell, Sebesta explained that he had known Carter’s family all of his life. The Sebestas hailed from Snook, in southeastern Burleson County, and the Carters lived just down the road, in Clay. “He was a heck of a basketball player,” said Sebesta of the man he sent to death row. The young man he remembered was “a little wimp,” not someone who was capable of cold-blooded murder. “He was the instigator, but he wasn’t the primary actor in this thing,” he said. “As far as complicity goes, I think it was Graves, Cookie, and then Carter.” It was the streetwise Graves, he held, who had wanted to “straighten things out” with Bobbie Davis. In his view, Graves, who throughout the trial had “stared straight ahead with steel-looking eyes,” was utterly, morally debased. Sebesta said he had received “bits and pieces of information” that Graves and Cookie were kissing cousins, a charge he had insinuated to the jury at Graves’s trial.

Still stung by the Fifth Circuit’s ruling, Sebesta told me that he had taken a polygraph exam, which he publicized in advance to local media, to prove that he had disclosed Carter’s statements to Garvie. After the first test was inconclusive, Sebesta took a second polygraph, using a different test structure, which he passed. (“In the opinion of this examiner, you have been completely truthful,” read the polygraph report that Sebesta provided to me.) Indeed, the former prosecutor has gone to extraordinary lengths to clear his name. Last year, he paid for space in the Caldwell and Brenham newspapers to publish a five-thousand-word letter in which he vigorously defended himself. “When I get backed in a corner, I come out fighting,” he told me. The seventy-year-old former prosecutor seemed keenly aware of his legacy. “We did not withhold evidence,” he said, his blue eyes insistent. “I couldn’t sleep at night if I would’ve done something like that.”

For the past four years, as Graves has awaited trial, he has been confined to the Burleson County jail, a colorless, low-slung building by the side of Texas Highway 36, in Caldwell. Unlike his last stay at the jail, Graves, who is now 45, is not housed side by side with other inmates; given the nature of the crime for which he stands accused, the county has relegated him to solitary confinement, citing concerns about his safety. Besides brief exchanges with the guards and phone calls that are limited to fifteen minutes, his only human interaction takes place on Wednesdays and Sundays, when he is allowed a twenty-minute visit by family and friends. He cannot touch his visitors; they talk by phone, separated by a sheet of Plexiglas.

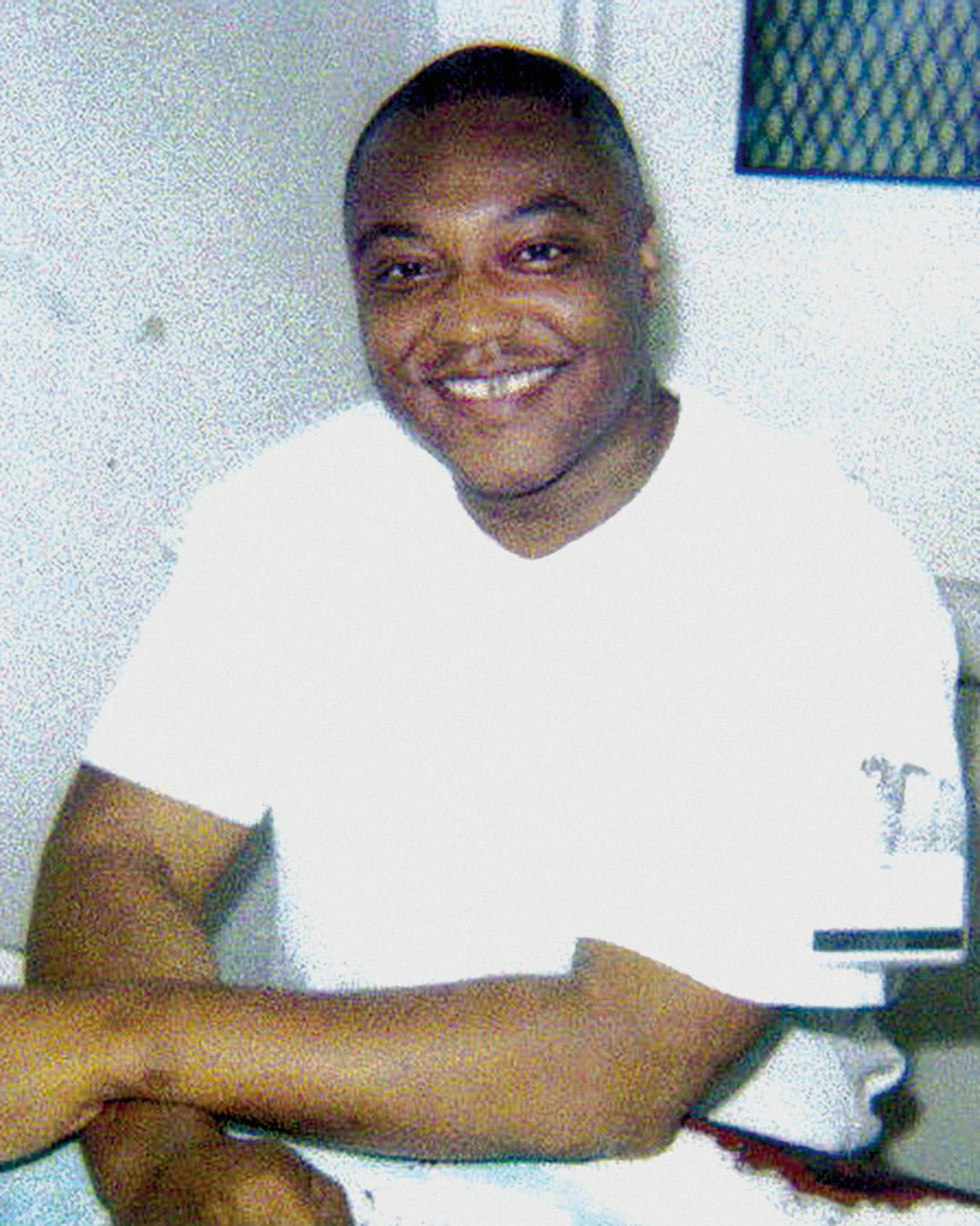

One day in June, I was escorted into a windowless, concrete room inside the jail, where Graves and I were permitted to sit face-to-face to discuss his case. A jailer led him in, and after his hands were unshackled, he took a seat across the table from me. The photos I had seen of him were taken when he was still a young man, but Graves is now a grandfather, and he has settled into middle age. His face was soft and round, his body thicker beneath his black-and-white-striped uniform.