I.

On April 12, 1987, Michael Morton sat down to write a letter. “Your Honor,” he began, “I’m sure you remember me. I was convicted of murder, in your court, in February of this year.” He wrote each word carefully, sitting cross-legged on the top bunk in his cell at the Wynne prison unit, in Huntsville. “I have been told that you are to decide if I am ever to see my son, Eric, again. I haven’t seen him since the morning that I was convicted. I miss him terribly and I know that he has been asking about me.” Referring to the declarations of innocence he had made during his trial, he continued, “I must reiterate my innocence. I did NOT kill my wife. You cannot imagine what it is like to lose your wife the way I did, then to be falsely accused and convicted of this terrible crime. First, my wife and now possibly, my son! Sooner or later, the truth will come out. The killer will be caught and this nightmare will be over. I pray that the sheriff’s office keeps an open mind. It is no sin to admit a mistake. No one is perfect in the performance of their job. I don’t know what else to say except I swear to God that I did NOT kill my wife. Please don’t take my son from me too.”

His windowless concrete cell, which he shared with another inmate, measured five by nine feet. If he extended his arms, he could touch the walls on either side of him. A small metal locker that was bolted to the wall contained one of the few remnants he still possessed from his previous life: a photograph of Eric when he was three years old, taken shortly before the murder. The boy was standing in the backyard of their house in Austin, playing with a wind sock, grabbing the streamers that fluttered behind it in the breeze. There was a picture too of his late wife, Christine—a candid shot Michael had taken of her years earlier, with her hair pinned up, still wet from a bath. She was looking away from the camera, but she was smiling slightly, her fingers pressed against her mouth. The crime-scene photos were still fresh in Michael’s mind, but if he focused on the snapshot, the horror of those images abated. Christine with damp hair, smiling—this was how he wanted to remember her.

The last time he had seen her was on the morning of August 13, 1986, the day after his thirty-second birthday. He had glanced at her as she lay in bed, asleep, before he left for work around five-thirty. He returned home that afternoon to find the house cordoned off with yellow crime-scene tape. Six weeks later, he was arrested for her murder. He had no criminal record, no history of violence, and no obvious motive, but the Williamson County Sheriff’s Office, failing to pursue other leads, had zeroed in on him from the start. Although no physical evidence tied him to the crime, he was charged with first-degree murder. Prosecutors argued that he had become so enraged with Christine for not wanting to have sex with him on the night of his birthday that he had bludgeoned her to death. When the guilty verdict was read, Michael’s legs buckled beneath him. District attorney Ken Anderson told reporters afterward, “Life in prison is a lot better than he deserves.”

The conviction had triggered a bitter custody battle between Christine’s family—who, like many people in Michael’s life, came to believe that he was guilty—and Michael’s parents. The question of who would be awarded custody of Eric was to be resolved by state district judge William Lott, who had also presided over Michael’s trial. If Christine’s family won custody, Michael was justifiably concerned that he would never see his son again.

Two weeks after sending his first entreaty to Lott, Michael penned another letter. “My son has lost his mother,” he wrote. “Psychological good can come from [seeing] his one surviving parent.” Ultimately, custody of the boy was awarded to Christine’s younger sister, Marylee Kirkpatrick. But at the recommendation of a child psychiatrist who felt that Eric should know his father, Lott agreed to allow two supervised visits a year. Marylee drove Eric to Huntsville every six months to see his father. He was four when the visits began.

At first, Eric was oblivious to his surroundings. He raced his Matchbox cars along the plastic tabletops in the visitation area, mimicking the sounds of a revving engine. He talked about the things he loved: dinosaurs, comic books, astronomy, his dog. As he grew older, he described the merit badges he had earned in Boy Scouts and his Little League triumphs. Marylee always sat beside him, her impassive expression impossible to decipher. For Eric’s sake, she seemed determined to make the mandated reunions—which she had strenuously opposed—as normal as possible. She flipped through magazines as Eric and his father spoke, sometimes glancing up to join in. Michael tried to pretend there was nothing unusual about the arrangement either, dispensing lemon drops he had purchased at the prison commissary and talking to his son about the Astros’ ups and downs or the Oilers’ failed attempts at a comeback. During the months that stretched between visits, he wrote letters to Eric, but Marylee did not encourage the correspondence, and it remained a one-way conversation.

“I’m not going to force you to come see me,” Michael told him. “You can come back anytime if you change your mind.” Before he walked away, he said to Marylee, “Take good care of my son for me.”

Over the years, as Eric got older, Michael would try not to register surprise at each new haircut and growth spurt, but the changes always startled him. He was dumbstruck the first time he heard Eric call Marylee “Mom.” The boy’s memories of his mother had, by then, receded. “Of course, I have lost him,” Michael wrote in his journal after one visit, when Eric was ten. “He knows little or nothing of me or the short time we spent together.”

Around the time Eric turned thirteen, the tenor of their visits changed. Eric was distant and impatient to leave. Michael knew that the boy had started asking questions; during a trip to East Texas to see his paternal grandparents, he had asked if it was true that his father had killed his mother. Fearful of alienating Eric any further, Michael never tried to engage him in a conversation about the case or persuade him that he had been wrongfully convicted. He assumed that Marylee would contradict any argument he made, and he doubted Eric would believe him anyway.

The silences that stretched between them became so agonizing that Michael often found himself turning to Marylee to make conversation. Two hours were allotted for their visits, but that was an eternity. “Well . . . ,” Marylee would say when they ran out of small talk.

“Yes,” Michael would agree. “It’s probably time.”

Their last meeting was so brief that Eric and Marylee barely sat down. Eric, who was fifteen, was unable to look Michael in the eye. “I don’t want to come here anymore,” he choked out.

Michael considered thanking Marylee for turning his son against him or telling Eric that everything he had been led to believe was a lie. But as he looked at his son, who stared hard at the floor, he kept those thoughts to himself. “I’m not going to force you to come see me,” Michael told him. “You can come back anytime if you change your mind.” Before he walked away, he said to Marylee, “Take good care of my son for me.”

II.

When Michael and Christine bought the house on Hazelhurst Drive, in 1985, northwest Austin had not yet been bisected by toll roads or swallowed up by miles of unbroken suburban sprawl. The real estate bust had brought construction to a standstill, and the half-built subdivision where they lived, east of Lake Travis, was a patchwork of new homes and uncleared, densely wooded lots. Although the Morton home had an Austin address, it sat just north of the Travis County line, in Williamson County—an area that, despite an incursion of new residents and rapid development, still retained the rural feel and traditional values of small-town Texas. Austin was seen as morally permissive, a refuge for dope smoking and liberal politics that Williamson County, which prided itself on its law-and-order reputation, stood against. In Georgetown, the county seat, bars and liquor stores were prohibited.

Their neighborhood was a place for newcomers, most of them young professionals with children. The Mortons arrived when Eric was a toddler, and Christine had quickly learned everyone’s name on their street, often stopping in the driveway after work to visit with the neighbors. Friendly and unguarded, with long brown hair and bright-blue eyes, she had a disarming confidence; she might squeeze the arm of the person she was talking to as she spoke or punctuate conversation with a boisterous laugh. Michael was slower to warm to strangers, and his neighbors on Hazelhurst, whom he never got to know well, found him remote, even prickly. (“He would spend the whole morning working in the yard and never look up,” one told me.) The Mortons’ next-door neighbor Elizabeth Gee, a lawyer’s wife and stay-at-home mother, often seemed taken aback by Michael’s lack of social graces. He made no secret of the fact that he found her comically straitlaced; he and Christine had gone out to dinner with the Gees once, and Michael had rolled his eyes when she had demurely looked to her husband to answer for her after the waiter asked if she wanted a drink.

Christine had grown up in the suburbs south of Houston and attended Catholic school, where she was a popular student and member of the drill team. Michael was rougher around the edges. His father’s job with an oil field service company had taken the family from Waco to a succession of small towns across Southern California before they finally settled in Kilgore, where Michael attended his last two years of high school. One day when Michael was sixteen, his father brought him along to an oil drilling site, and Michael sat in the car and watched as his dad slogged through his work in an icy rain. The experience forever cured him of wanting to toil in the oil patch. He went to Stephen F. Austin State University, in Nacogdoches, where, in 1976, he met Christine in a psychology class. For their first date, he took her out in a borrowed Corvette, and not long afterward, she confided to her friend Margaret Permenter that she thought he might be “the one.” “Mike was pretty reserved, but he was nice and handsome, with one of those Jimmy Connors haircuts,” Permenter told me. “Chrissy was more committed than he was at first.”

Christine followed Michael to Austin in 1977 after he dropped out of SFA. They had hoped to finish their degrees at the University of Texas, but the plan fizzled when they learned that many of their credits would not transfer. Instead, Michael landed a job stocking shelves at night at a Safeway and eventually became a manager, overseeing toiletries and housewares. (He would also later start a side business cleaning parking lots.) He and Christine spent their weekends at Lake Travis, waterskiing and buzzing around in the jet boat that Michael and several of his college buddies had pooled their money to buy. He became an avid scuba diver, and on his days off, he would explore Lake Travis for hours.

“When they argued, they were both very vocal,” Christine’s best friend, Holly Gersky, told me. “That’s how their marriage worked. They got everything out in the open.”

Michael and Christine were affectionate with each other but also voluble about their problems. “It was not Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? but they had what I would call passionate conversations,” Jay Gans, a former roommate of Michael’s, told me. “There was nothing subtle about either one of them. They would argue very intensely, and eventually one of them would start cracking up, and not long after that, they would disappear into the bedroom.” They married in 1979.

The candor with which they spoke to each other could unnerve even their closest friends. “When they argued, they were both very vocal,” Christine’s best friend, Holly Gersky, told me. “That’s how their marriage worked. They got everything out in the open.” They bickered constantly, and no subject was too inconsequential. After they bought the house on Hazelhurst, the topic of the landscaping spawned pitched battles over everything from the size of the deck that Michael was building to the prudence of Christine’s decision to plant marigolds at the end of the driveway, beyond the sprinkler’s reach. Michael also liked to rib Christine, and his sense of humor could be sarcastic and sometimes crude. A running gag between them involved Michael calling out, “Bitch, get me a beer!”—something they had once overheard a friend of a friend shout at his girlfriend. Christine would respond by telling Michael to go screw himself. “He teased her a lot, and he would go right up to the line of what was acceptable, and sometimes he went over it,” Gersky said. Referring to an attractive friend of theirs who stopped by the house one day wearing shorts, he told Christine, “Now, that’s the way you should look.”

Yet the connection between them ran deep. They weathered a tragedy in the early years of their marriage, when Christine suffered a late miscarriage with her first pregnancy, in 1981. She had been four and a half months pregnant at the time. If not for Michael, she later wrote to his mother, she could not have survived the anguish of their loss. They were overjoyed when she became pregnant again less than two years later and elated when she reached her ninth month without any serious complications.

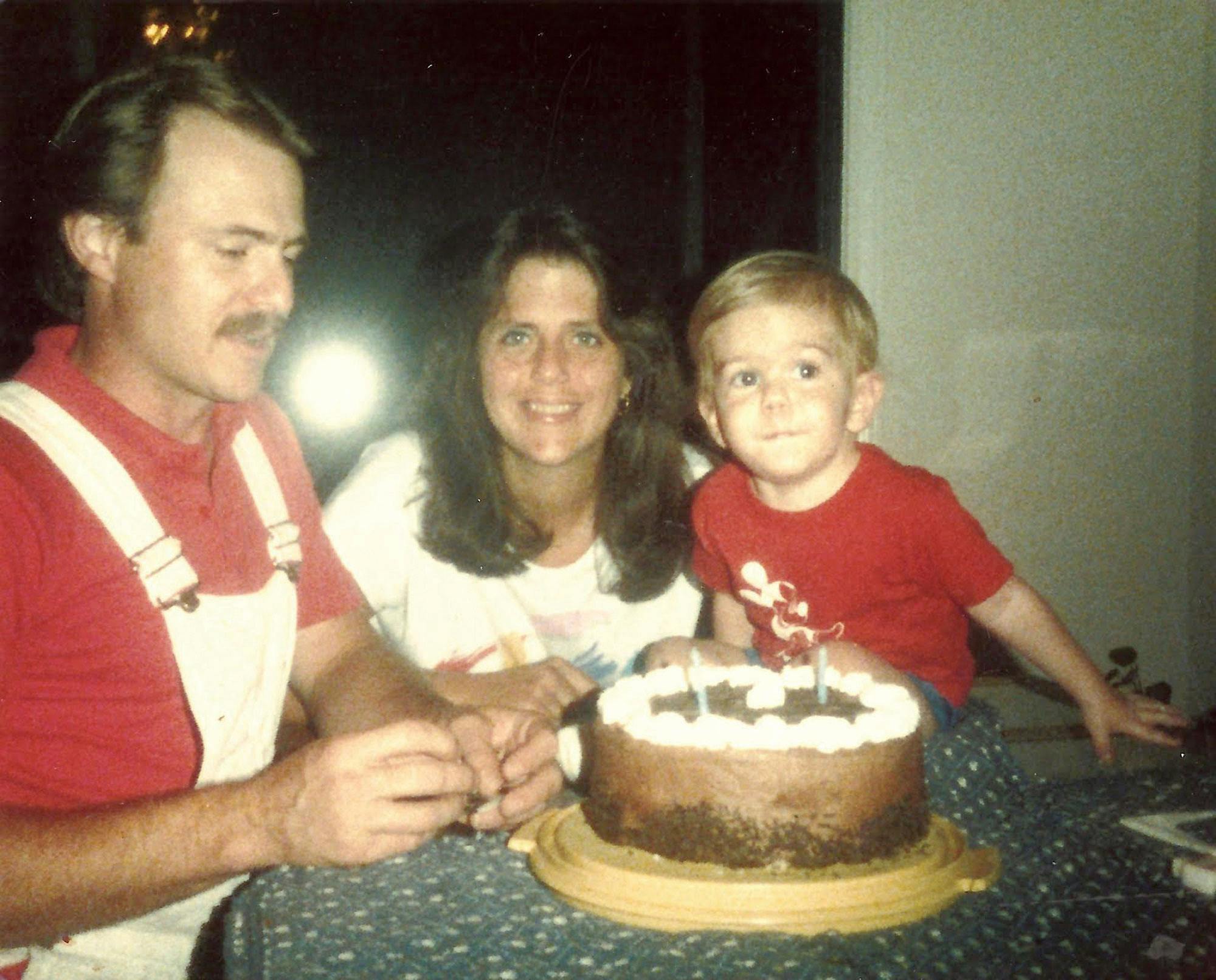

But within an hour of Eric’s birth, in the summer of 1983, the Mortons were informed that their son had major health problems. Emergency surgery had to be performed that day to repair an abnormality in his esophagus. During the three-week stay in the neonatal unit that followed, doctors discovered that Eric also had a congenital heart defect. The condition prevented his blood from receiving the proper amount of oxygen. Doctors advised Michael and Christine that their son would not survive to adulthood unless he had open-heart surgery. But he could not undergo the procedure until he became bigger and hardier; he had to either reach his third birthday or weigh thirty pounds. Operating sooner carried too much risk. Until then, there was nothing that Michael and Christine could do but wait.

Together, they devoted themselves to caring for Eric. If he exerted himself, he turned blue, a symptom that only worsened as he got older. As a two-year-old, he would sit quietly and draw or leaf through picture books. He tired so easily that if he ran around the living room once or twice he would fall to the floor from exhaustion. Christine dropped him off on weekday mornings at a day care in Austin, an arrangement that allowed her to continue working full-time as a manager at Allstate, but in the evenings, she was reluctant to leave him with a babysitter. “Mike thought it was important to take a break and do something fun from time to time, but Chris felt she needed to stay close to home,” Gersky said. “They were both so worried about Eric and keeping him healthy until his surgery, and that put a lot of stress on their marriage.”

The strain on the relationship became obvious. Nothing stayed below the surface for long, and Michael’s wisecracks began to have a harder edge to them. He openly complained to friends that he and Christine were not having enough sex and that she needed to lose weight. “His comments stung,” Gersky said. “Chris shrugged them off—she would say, ‘Just ignore him’—but they made other people uncomfortable. The bottom line was that Mike loved her, she loved him, and they adored Eric, and he was the most important thing to both of them, but they were definitely having a difficult time.”

In June 1986, shortly before Eric’s third birthday, the Mortons drove to Houston for his operation. Christine took a leave of absence and Michael used all of his vacation time so they could both be present for Eric’s three-week hospital stay. They each took turns sleeping at his bedside so that he was never alone. The surgery went smoothly, and by the time he was discharged, he seemed to be a different child. The transformation was dramatic, even miraculous. For the first time in his life, his cheeks were pink and he was full of energy. When they returned home, Michael and Christine watched in amazement as he gleefully ran up and down the sidewalk outside their house, laughing.

Six weeks later, on the morning of Wednesday, August 13, Michael rose before dawn and dressed for work, quietly moving around the bedroom so as not to wake Christine. They had celebrated his birthday the night before, and it had been a fun evening at first. They brought Eric with them to the City Grill, a trendy restaurant in downtown Austin, for a rare night out. Michael and Christine smiled at each other as their son, now the picture of health, ate from his mother’s plate and then dug into a bowl of ice cream. Eric nodded off in the car on the way home, and when they arrived, Michael carried him to his room and tucked him in. Once he and Christine were alone, Michael put on an adult video that he had rented for the occasion, hoping to spark some romance. But not long after they began watching the movie, Christine fell asleep on the living room floor. Hurt and angry, Michael retreated to the bedroom without her. Later, when she came to bed, she leaned over and kissed him. “Tomorrow night,” she promised.

The episode had rankled Michael, and before he went to the kitchen that morning to fix himself something to eat, he glanced over at Christine; she lay sleeping in their water bed, in a pink nightgown she had put on for his birthday, her dark hair fanned out across her pillow. After he ate breakfast, he wrote her a note, which he propped up on the vanity in the bathroom so she would be sure to see it before she left for work:

Chris, I know you didn’t mean to, but you made me feel really unwanted last night. After a good meal, we came home, you binged on the rest of the cookies. Then, with your nightgown around your waist and while I was rubbing your hands and arms, you farted and fell asleep. I’m not mad or expecting a big production. I just wanted you to know how I feel without us getting into another fight about sex. Just think how you might have felt if you were left hanging on your birthday.

At the end, he scribbled “I L Y”—“I love you”—and signed it “M.”

It was still dark outside when he pulled out of the driveway sometime after 5:30 that morning. When he arrived at the Safeway, he rapped his keys against the glass doors out front, and the produce manager, Mario Garcia, let him in. He punched his time card at 6:05 a.m. Throughout the morning, he and Garcia stopped to talk about their mutual interest in scuba diving. They made plans to go on a dive the next day, which they both had off from work. Michael agreed to call Garcia that evening so they could pick a place to meet.

He left work shortly after two o’clock that afternoon and stopped at the mall to run a few errands. Afterward, at around three-thirty, he went to pick up Eric. Mildred Redden, an older woman who looked after the boy in her home along with several other children, was surprised to see Michael. She told him that she had neither seen Eric nor heard from Christine all day. Alarmed, Michael reached for the phone and dialed home.

The phone rang several times and then a man whose voice he did not recognize picked up. For a moment, Michael thought it might be Christine’s brother, who was in town. “Can I help you?” the man asked.

“Yeah, I’m calling my house,” Michael said.

“Say, where are you?” the man asked.

“I’m over at the Reddens’,” Michael replied.

“Over where? This is the sheriff.”

“What’s going on?” Michael said. “I live there.”

“Well, we need to talk to you, Mike.”

“I’ll be there in ten minutes,” he said, sounding panicky.

“Okay,” the sheriff said. “Just take it easy though, okay?”

Michael bolted for the door so quickly that Redden, who had turned for a moment to place a baby in a swing, never saw him leave.

III.

To his admirers, Williamson County sheriff Jim Boutwell was larger than life; to his detractors, he was a walking cliché. The amiable, slow-talking former Texas Ranger wore a white Stetson, and he took his coffee black and his Lucky Strikes unfiltered. As a young pilot for the Department of Public Safety, he was famous for having flown a single-engine airplane around the University of Texas Tower in 1966 while sniper Charles Whitman took aim at bystanders below. (Boutwell succeeded in distracting Whitman and drawing his fire as police officers moved in, though he narrowly missed being shot himself.) Law enforcement was in his blood—his great-grandfather John Champion had briefly served as the Williamson County sheriff after the Civil War—and stories were often repeated about Boutwell’s ability to win over almost anyone, even people he was about to lock up. More than once, he had defused a tense situation by simply walking up to a man wielding a gun and lifting the weapon right out of his hands. At election time, Boutwell always ran unopposed.

But Boutwell also played by his own rules, a tendency that had, in one notorious case, resulted in a botched investigation whose flawed conclusions reverberated through the cold-case files of police departments across the country. In 1983, three years before Christine’s murder, Boutwell coaxed a confession from Henry Lee Lucas, a one-eyed drifter who would, within a year’s time, be considered the most prolific serial killer in American history. Earlier that summer, Lucas had pleaded guilty to two murders—in Montague and Denton counties—and then boasted of committing at least a hundred more. At the invitation of the sheriff of Montague County, his old friend W. F. “Hound Dog” Conway, Boutwell had driven to Montague to question Lucas about an unsolved Williamson County case known as the Orange Socks murder. (The victim, who was never identified, was wearing only orange socks when her body was found in a culvert off Interstate 35 on Halloween in 1979.) After a productive initial interrogation, Boutwell brought Lucas back to Williamson County and elicited further details from him about the killing, but his methods were unethical at best. “He led Henry to the crime scene, showed him photos of the victim, and fed him information,” reporter Hugh Aynesworth, whose 1985 exposé on Lucas for the Dallas Times Herald was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize, told me. “Henry didn’t even get the way he killed her right on the first try: he said Orange Socks must have been stabbed, instead of strangled. His ‘confession’ was recorded four times so it could be refined.”

Boutwell played by his own rules, a tendency that had, in one notorious case, resulted in a botched investigation whose flawed conclusions reverberated through the cold-case files of police departments across the country.

Lucas, who was held at the Williamson County jail, seemed to like the attention. In subsequent interviews with Boutwell, the number of murders he claimed to have committed climbed to a staggering 360. Despite signs that Lucas was taking everyone for a ride, the Williamson County DA’s office—which had nothing but his confession to connect him to the Orange Socks killing—charged him with capital murder. Among the many problems with the state’s case was the fact that Lucas had cashed a paycheck in Jacksonville, Florida, nearly one thousand miles away, a day after the killing. When the case went to trial, in 1984, his job foreman testified that he had seen Lucas at least three times on the day the murder occurred. (Prosecutors countered by laying out a time line that allowed Lucas to kill his victim and return to Jacksonville without a second to spare.) During a break in the trial, Boutwell speculated that jurors would see past the case’s myriad contradictions. “Even if they don’t believe Henry did this one, they know he done a lot of them, and they’ll want to see him put away for good,” Boutwell observed. Lucas was found guilty and sentenced to death.

After his conviction, Lucas remained in the Williamson County jail, where he would eventually confess to committing more than six hundred murders. He soon became a kind of macabre celebrity. Investigators from across the country traveled to Georgetown to interview him about their unsolved cases, but the integrity of Lucas’s confessions was dubious. A task force manned by Boutwell and several Texas Rangers often briefed him before detectives arrived; one Ranger memo stated that in order to “refresh” Lucas’s memory, he was furnished with crime-scene photos and information about his supposed victims. Provided with milk shakes, color TV, and assurances that he would not be transferred to death row as long as he kept talking, Lucas obliged. He gave visiting investigators enough lurid details that he was eventually indicted for 189 homicides. Not a single fingerprint, weapon, or eyewitness ever corroborated his claims. Even as his stories grew more and more outlandish—he declared that he had killed Jimmy Hoffa and delivered the poison for the 1978 Jonestown massacre in Guyana—Boutwell never washed his hands of him. The sheriff, who was interviewed by reporters from as far away as Japan, appeared to enjoy the limelight.

Years later, after Boutwell died of lymphatic cancer, Governor George W. Bush took the unusual step of commuting Lucas’s death sentence to life in prison. “While Henry Lee Lucas is guilty of committing a number of horrible crimes, serious concerns have been raised about his guilt in this case,” Bush announced in 1998, on the eve of Lucas’s execution for the Orange Socks murder. By then, it was no secret that the investigation Boutwell had kick-started was a fiasco. Aynesworth’s exhaustive Times Herald series had used work records, receipts, and a trail of documents to show that Lucas was likely responsible for no more than three of the slayings credited to him. In the spring of 1986 Texas attorney general Jim Mattox had issued a scathing report about the Lucas “hoax” and the investigators who had perpetuated it.

This was just a few months before the murder of Christine Morton, but when Boutwell arrived at the crime scene that day, Mattox’s report probably wasn’t weighing too heavily on his mind. It might have hurt his reputation in Austin, 28 miles south, but in Georgetown he remained untarnished. “He’d go around town, boy, and everyone would clap him on the back,” Aynesworth told me. “He was a hero.”

The house on Hazelhurst was blocked off with crime-scene tape when Michael returned home. Despite the oppressive heat that August afternoon, many of his neighbors were standing outside in their yards; they stopped talking when they saw him pull up. Michael sprinted across the lawn and tried to push his way inside, past the sheriff’s deputies and technicians from the DPS crime lab who were already on the scene, but several officers converged on him. “He’s the husband,” Boutwell called out, once Michael had identified himself.

Michael was breathing hard. “Is my son okay?” he asked.

“He’s fine,” Boutwell said. “He’s at the neighbors’.”

“How about my wife?”

The sheriff was matter-of-fact. “She’s dead,” he replied.

Boutwell led Michael into the kitchen and introduced him to Sergeant Don Wood, the case’s lead investigator. “We have to ask you a few questions before we can get your son,” Boutwell told him. Dazed, Michael took a seat at the kitchen table. He had shown no reaction to the news of Christine’s death, and as he sat across from the two lawmen, he tried to make sense of what was happening around him. Sheriff’s deputies brushed past him, opening drawers and rifling through cabinets. He could see the light of a camera flash exploding again and again in the master bedroom as a police photographer documented what Michael realized must have been the place where Christine was killed. He could hear officers entering and exiting his house, exchanging small talk. Someone dumped a bag of ice into the kitchen sink and stuck Cokes in it. Cigarette smoke hung in the air.

Bewildered, Michael looked to the two law enforcement officers for answers. “She was murdered?” he asked, incredulous. “Where was my son?” Boutwell was not forthcoming. The sheriff said only that Christine had been killed but that they did not yet know what had happened to her.

From the start, Boutwell treated Michael not like a grieving husband but like a suspect.

By then, Boutwell had been in the house for two and a half hours. Sheriff’s deputies had arrived earlier that afternoon, responding to a panicked phone call from the Mortons’ next-door neighbor Elizabeth Gee, who had spotted Eric wandering around the Mortons’ front yard by himself, wearing only a shirt and a diaper. Alarmed, she let herself in to the Morton home and called out for her friend. Hearing nothing, she looked around the house. After searching the home several times, she finally discovered Christine’s body lying on the water bed, with a comforter pulled up over her face. A blue suitcase and a wicker basket had been stacked on top of her. The wall and the ceiling were splattered with blood. Her head had been bludgeoned repeatedly with a blunt object.

From the start, Boutwell treated Michael not like a grieving husband but like a suspect. The sheriff had never tried to reach Michael to notify him of Christine’s death, and once he arrived, their conversation at the kitchen table began with Boutwell’s reading Michael his Miranda rights. His opinion of Michael was informed by the note left in the bathroom for Christine, which established that Michael had been angry with her in the hours leading up to her murder. Boutwell had read it shortly after arriving at the house. Michael’s lack of emotion at the news of her death did not help to dispel the sheriff’s suspicion that the murder had been a domestic affair. Odd details about the crime scene only reinforced his hunch. There were no indications of a break-in, a fact that Boutwell would repeat to the media in the weeks to come. (Though it was true that there were no signs of forced entry, the sliding-glass door in the dining area was unlocked.) Robbery did not appear to have been the motive for the crime; Christine’s purse was missing, but her engagement ring and wedding band were lying in plain sight on the nightstand. Other valuables, like a camera with a telephoto lens, had also gone untouched.

Michael, who did not request an attorney, was cooperative and candid during his conversation with Boutwell and Wood. When he was asked to account for his time, beginning with the previous morning, he described his day in painstaking detail, down to the particular kind of fish Christine had eaten for dinner and the color of socks he had worn to bed. As the afternoon wore on, they pressed him about tensions in his marriage and whether either of them had ever had an affair. Sensing the drift of the conversation, Michael said at one point, “I didn’t do this, whatever it is.” Boutwell, who had not examined Christine’s injuries, had incorrectly surmised that she had been shot in the head at close range, and many of his questions focused on the guns that Michael kept in the house. Michael liked to hunt, and he had seven guns in all. As he spoke, he reeled off their makes and models according to caliber. When he listed his .45 automatic, Boutwell and Wood glanced up from their legal pads. “Is my .45 missing?” Michael asked. The pistol could not be accounted for—they had already searched his cache of firearms and hadn’t seen it—but neither man answered him.

Growing more and more uneasy with their line of questioning, Michael finally erupted. “I didn’t kill my wife,” he insisted. “Are you fucking crazy?”

The conversation stretched on for the rest of the afternoon. Afterward, Wood escorted Michael to a neighbor’s home, where Eric had been playing. Relieved to see his father, Eric ran to him. Michael fell to his knees and embraced the boy. For the first time since the ordeal had begun, he broke down and wept.

People would later remark on how strange it was that Michael did not go to a hotel or a friend’s house that night, but in the fog of shock and grief, he and Eric went home. Michael did not ask what, if anything, the three-year-old had witnessed. (Wood had already tried to question the boy but was unable to get any information from him.) Instead, Michael offered his son assurances that everything would be all right. The house was in disarray; furniture was overturned, clothes were strewn across the bedroom floor, and the kitchen was littered with empty Coke cans and cigarette butts. Intent on reclaiming some sense of normalcy, Michael pulled down the yellow crime-scene tape outside and began to clean up. As it grew dark, he went from room to room, turning on lights. When exhaustion finally overtook him, he crawled into Eric’s bed and lay beside him, holding the boy close. The lights stayed on all night.

The next morning, Orin Holland, who lived one block north of the Mortons, on Adonis Drive, stopped a sheriff’s deputy who was canvassing the neighborhood to share what he thought might be important information. Holland told the officer that his wife, Mary, and a neighbor, Joni St. Martin, had seen a man park a green van by the vacant, wooded lot behind the Morton home on several occasions. Holland went on to explain that his wife and St. Martin had also seen the man get out of the van and walk into the overgrown area that extended up to the Mortons’ privacy fence. Shortly after Holland talked to the deputy—either that night or the next, Holland told me—a law enforcement officer visited his home. “His purpose was not to ask us questions about what we had seen but to reassure us,” Holland said. “Everyone was very unnerved at that time, and he came to say that we shouldn’t worry and that we were not in any danger. He didn’t overtly say, ‘We know who did it,’ but he implied that this was not a random event. I can’t remember his exact words, but the suggestion was that the husband did it.”

“We kept waiting for the police to come talk to us, but they never did,” Joni told me. “Eventually, we figured the evidence led them in another direction.”

The St. Martins had also contacted the sheriff’s office about the van. “Joni remembers me seeing the van early in the morning on the day Christine was killed, when I left to go to work,” her ex-husband, David, told me. “I trust Joni’s memory more than mine, but twenty-six years later, I can’t say exactly when I saw it.” Still, the van made an impression on both of them. “There were only two houses on our street: the Hollands’ and ours,” Joni explained. “People dumped trash in that area, so if we saw a vehicle we didn’t know, we paid attention.” After learning of Christine’s murder, David called the sheriff’s office. “We kept waiting for the police to come talk to us, but they never did,” Joni told me. “Eventually, we figured the evidence led them in another direction.” Like most people in the neighborhood, she and David did not know Michael particularly well. “We’d said hi at the mailbox before, but that was it—he pretty much kept to himself,” Joni told me. “So when he was arrested, we thought, ‘Well, what do we know? They must have something on him.’ ”

In fact, what little physical evidence had been recovered from the crime scene pointed away from Michael. Fingerprints lifted from the door frame of the sliding-glass door in the dining area did not match anyone in the Morton household. All told, there were approximately fifteen fingerprints found at the house—including one lifted from the blue suitcase that was left on top of Christine’s body—but they were never identified. A fresh footprint was also discovered just inside the Mortons’ fenced-in backyard. The most compelling piece of evidence was discovered by Christine’s brother, John Kirkpatrick, who searched the property behind the house the day after her murder. Just east of the wooded lot where the man in the green van had been seen by the Mortons’ neighbors, there was an abandoned construction site where work on a new home had come to a halt. John walked around the site, looking for anything that might help illuminate what had happened to his sister. As he examined the ground, he spotted a blue bandana lying by the curb. The bandana was stained with blood.

John immediately turned the bandana over to the sheriff’s office, but its discovery did not spur law enforcement to comb the area behind the Morton home for additional evidence. Either the significance of the bandana was not understood, perhaps because investigators had failed to follow up on the green van lead, or, worse, it was simply ignored.

When John handed over the bandana that afternoon, Boutwell and Wood were already absorbed by another development in the case. Based on an analysis of partially digested food found in Christine’s stomach, the medical examiner had estimated that she had been killed between one and six o’clock in the morning (Michael had, by his own account, been at home with her until five-thirty). The results did not necessarily implicate Michael, but they did not clear him of suspicion either. And neither did the medical examiner’s finding that Christine had not been sexually assaulted. Neither rape nor robbery appeared to have motivated her killer, but the savage nature of the beating—eight crushing blows to the head—seemed to suggest that rage had played a part.

A few days later, Boutwell met with Michael, Marylee, and Christine’s parents, Jack and Rita Kirkpatrick, to update them on the progress of the investigation. Michael had always enjoyed a cordial relationship with his wife’s family, but the sheriff’s comments that day quickly erased whatever goodwill existed between them. As Boutwell comforted the Kirkpatricks with the assurance that he would find Christine’s killer, he made it clear that Michael had not yet been ruled out as a suspect. “I’d like to show you some photos and update you on the progress of the investigation,” Boutwell said. “But I can’t show you anything if he’s”—the sheriff nodded at Michael—“in the room.” By the time Christine’s funeral was held later that week, in Houston, the uneasiness between Michael and the Kirkpatricks was obvious. “I noticed Mike standing off by himself afterward, and I could tell something wasn’t right,” a friend of the Mortons’ told me. “Chris’s brother, John, told me there were some questions about Mike. He said, ‘I’m heading back to Austin to look into some things.’ ”

Over the next few weeks, dozens of people who had known Michael and Christine—from close friends to co-workers and passing acquaintances—were visited by Wood. A former truck driver and small-town police chief, he was hardly a seasoned homicide detective; he had been promoted to the position of investigator only seven months earlier. But he was diligent, sometimes producing as many as four reports a day, and he often reviewed his handwritten notes with the sheriff before typing up his findings. Boutwell’s unwavering focus on Michael left Christine’s best friend, Holly Gersky, who spent days on end being interrogated at the sheriff’s office, deeply shaken. “I knew Chris’s routine, I knew about her marriage, I knew everything they wanted to know about, so they had a lot of questions for me,” she explained. “The whole time, I kept insisting that Mike could never have hurt Chris. I told them that he was incapable of abandoning Eric. One morning Sheriff Boutwell sat me down. He didn’t raise his voice—he was to the point—but he had a very big, intimidating presence. He said, ‘You’re either lying or there’s something you’re not telling us.’ ”

Michael passed two lie detector tests in the weeks that followed and cooperated fully with the investigation, answering another round of questions from Boutwell and Wood without a lawyer present. He gave them consent to search his black Datsun pickup, and he provided them with samples of his hair, saliva, and blood. (Before the advent of DNA testing, in the nineties, forensic tools—such as blood-typing and hair analysis—were relatively primitive. They were effective at eliminating suspects, but they could not pinpoint a perpetrator’s identity.) No physical evidence was ever found that tied Michael to the murder.

Still, Boutwell stuck to his theory of the case, telling a local newspaper, Hill Country News, that footprints found near the scene of the crime had been determined to have no connection to the killing and that blood stains discovered at a nearby work site—a reference to the blue bandana—were believed to have resulted from a minor construction accident. No doubt mindful of how an unsolved murder might unsettle the real estate developers and new families who were moving in to Williamson County, the sheriff sought to allay concerns about the safety of the community. Above all, Boutwell emphasized, Christine’s murder had not been random. “I feel confident to say there is no need for public alarm, because I seriously doubt that we have a serial murderer running loose in the area,” he said.

Of all the nightmarish possibilities that Michael turned over in his mind about what might have happened on the day Christine was killed, he was the most preoccupied by the possibility that Eric had witnessed the attack or had been harmed in some way himself. Certain details about the crime scene—that the blinds, which Christine always opened when she woke up, remained closed; that she had still been wearing her nightgown—suggested to him that she had been murdered shortly after he left for work, and so he held out hope that Eric had slept through the ordeal. He was heartened when Jan Maclean, a child therapist he had arranged for Eric to talk to, told Michael that his son manifested the usual signs of separation anxiety that often follow the death of a parent, but nothing indicated that the boy had himself been victimized.

Then, several weeks after the funeral, Eric said something that knocked the breath out of him. Michael was on his hands and knees in the master bathroom, scrubbing the bathtub, when Eric walked up behind him. The boy stared at the tub and looked up at the shower, studying it. “Daddy,” the three-year-old said, turning to him. “Do you know the man who was in the shower with his clothes on?”

“Daddy,” the three-year-old said, turning to him. “Do you know the man who was in the shower with his clothes on?”

Michael sat back, stunned. He had no doubt that Eric was speaking of the man who had killed Christine. The boy’s question dovetailed with details from the crime scene; there had been blood on the bathroom door. Hesitant to say anything that might upset his son, Michael did not probe further. “I don’t know him,” Michael said finally. “But I think if you have any questions about him, you should ask Jan.”

Maclean would never glean any more details from Eric, and Michael did not disclose the boy’s statement to the sheriff’s office. Given how aggressively Boutwell and Wood had questioned him, Michael did not want them anywhere near his son. At the urging of a friend, he retained two well-regarded Austin lawyers, Bill Allison and Bill White, who advised him to stop talking to law enforcement. By then, Michael had lost any confidence that Boutwell and his deputies would ever find Christine’s killer.

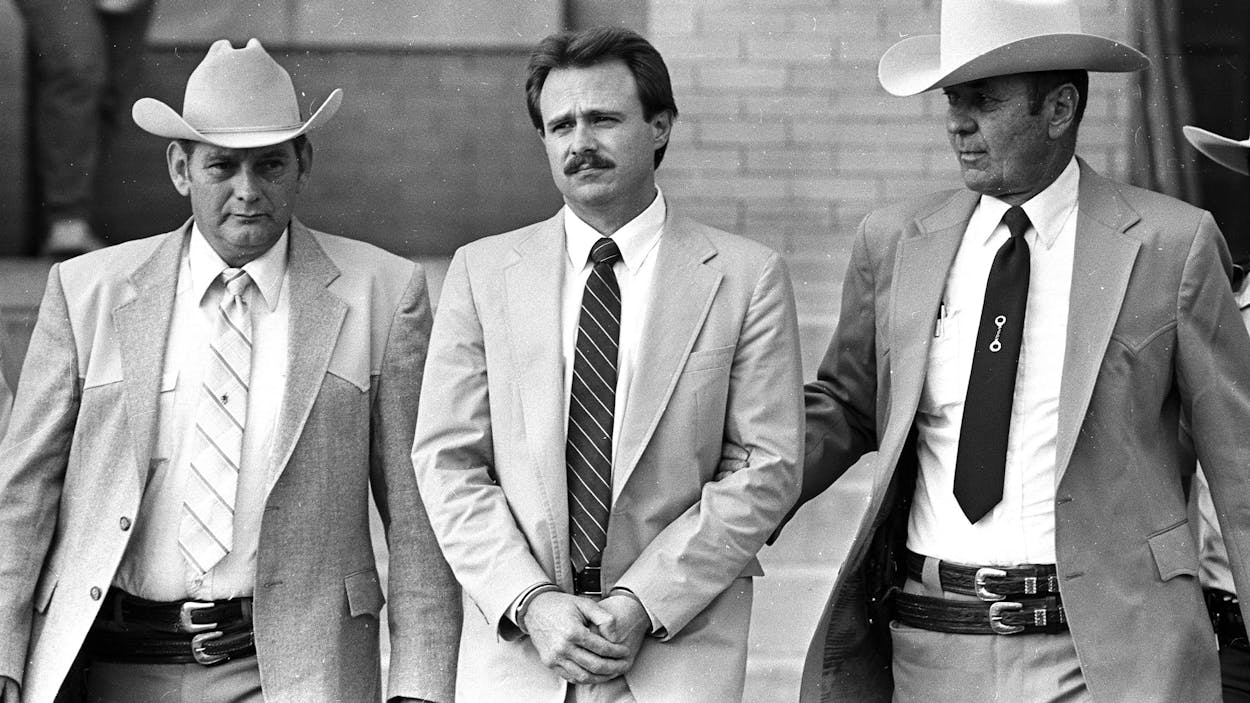

Just before dinnertime on September 25, Michael heard the doorbell ring. He turned off the stove and grabbed Eric, hoisting the boy onto his hip. When he opened the door, he saw Boutwell and Wood standing on his front porch. Boutwell had a warrant for his arrest. Though the sheriff could have let Michael turn himself in at a prearranged time, giving him enough notice to make a plan for Eric’s care, Boutwell had instead chosen to surprise him at home. “You’ve got to be kidding me,” Michael said.

The last time Eric had seen police officers was the day his mother was killed, and as he was pulled from Michael’s arms and handed to their neighbor Elizabeth Gee, he became hysterical. Boutwell put Michael in handcuffs and led him down the front walkway. Michael turned to see Eric, his arms outstretched, screaming for him.

IV.

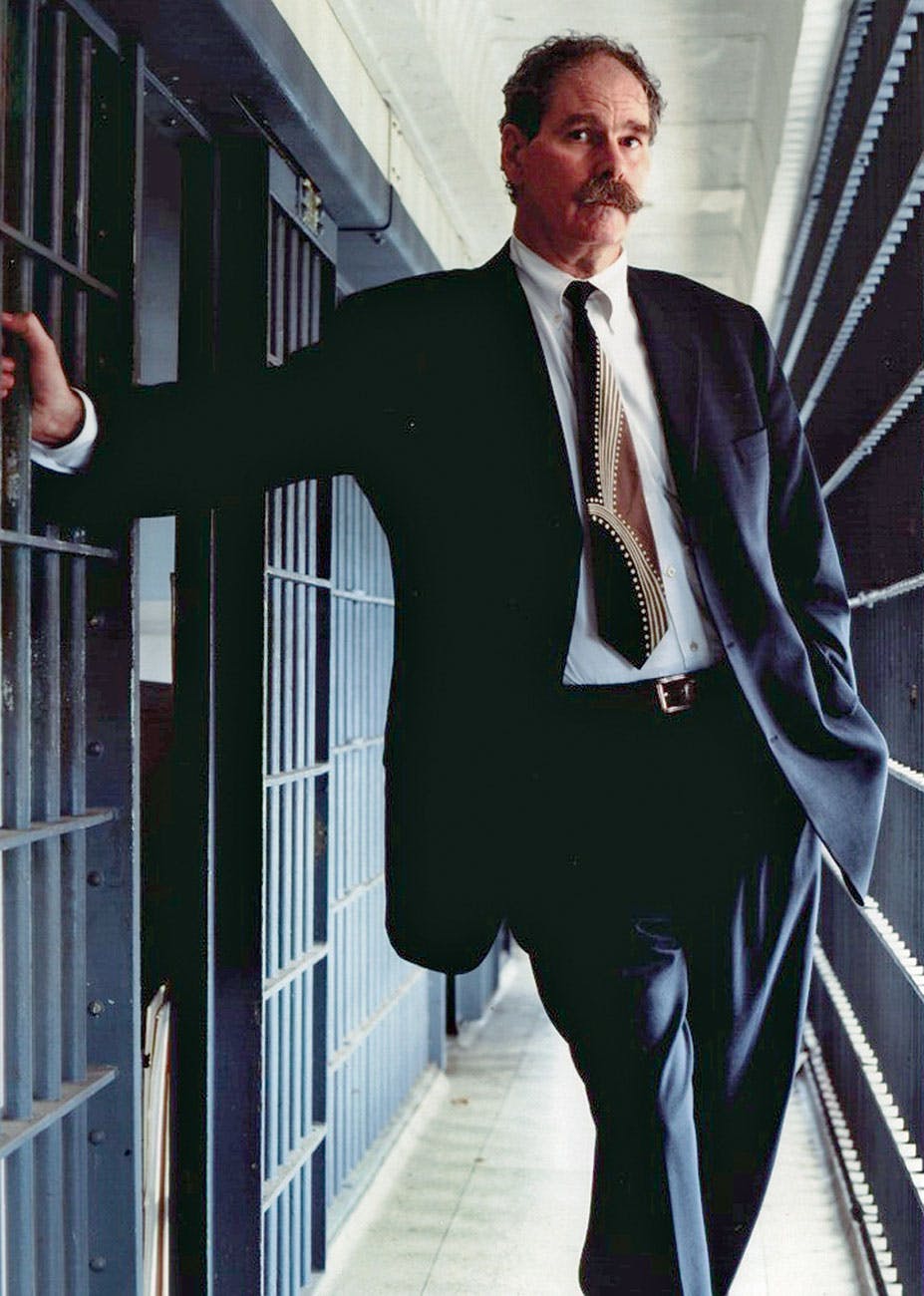

Perhaps no sheriff and district attorney had a closer working relationship than Jim [Boutwell] and I had,” wrote Williamson County DA Ken Anderson in his 1997 book, Crime in Texas: Your Complete Guide to the Criminal Justice System. “We talked on the phone daily and, more often than not, drank a cup of coffee together.” The two men frequently met at the L&M Cafe, a greasy spoon just down from the courthouse square in Georgetown. There, wrote Anderson, “we painstakingly pieced together circumstantial murder cases. We debated the next step of an investigation. . . . The downfall of more than one criminal doing life in the state prison system began with an investigation put together on a coffee-stained napkin at the L&M.”

Anderson, whose family moved from the East Coast to Houston when he was a teenager, had formed his early impressions of the legal profession from watching Gregory Peck in To Kill a Mockingbird and Spencer Tracy in Inherit the Wind. He saw himself as one of the good guys. He had enrolled in UT Law School in the wake of the Watergate hearings, when his politics were left-leaning and his sympathies lay with defending people, not prosecuting them. After graduation, he worked as a staff attorney representing the ultimate underdogs: three-time offenders serving life sentences at a prison outside Huntsville. But the experience left him profoundly disillusioned; he often felt that he was being misled by his clients. “They were innocent, every one of them,” he later told the Austin American-Statesman. “Even if you were wet behind the ears, liberal, fresh-graduated out of law school, you realized they were lying pretty quickly.”

A prominent Austin defense attorney once quipped that Anderson had “one foot in each century—that being the nineteenth and the twentieth.”

Anderson’s ideology took a hard right turn in 1980, when he joined the Williamson County DA’s office. He quickly became an indispensable first assistant to district attorney Ed Walsh, whose ascent had paralleled the county’s rapid growth. Before Walsh was elected, in 1976, there had been no full-time district attorney; at the time, the county’s population hovered at around 49,000 people, about one tenth what it is today. Walsh had run on a tough-on-crime platform that promised convictions and jail time for drug dealing—a campaign pledge he made good on. But while Walsh was an amiable figure who enjoyed a good rapport with the defense bar, his first assistant quickly developed an unforgiving reputation, often taking a harder line on punishment than his boss did. Anderson routinely asked for, and won, harsh sentences and fought to keep offenders in prison long after they became eligible for parole. A prominent Austin defense attorney once quipped that Anderson had “one foot in each century—that being the nineteenth and the twentieth.”

His view of the world, which would shape the modern-day Williamson County DA’s office, was strictly black and white. “Ken did not see grays,” said one attorney who practiced with him in the eighties. “He felt very strongly about the cases he was working on.” Intense and driven, he poured himself into each case he prosecuted, preparing for trial with scrupulous attention to detail. By his own admission, he was not so much a brilliant lawyer as a meticulous one. He was also famously adversarial, sharing as little information with defense attorneys as possible through a firm “closed file” policy. His job, as he saw it, was to fight “the bad guys,” and the struggle between the forces of good and evil was a common theme in his writing and courtroom oratory. “When you go home tonight, you will lock yourselves in your house,” he often reminded jurors during closing arguments. “You will check to see that you locked your windows, that your dead-bolted doors are secure. Perhaps you will even turn on a security system. There is something very wrong with a society where the good people are locked up while the criminals are running free on the street.”

Boutwell, who was a generation older than him, loomed large in the young prosecutor’s imagination. The sheriff was “a lawman from the tip of his Stetson to the soles of his cowboy boots,” Anderson rhapsodized in Crime in Texas. “I admire and respect all the Jim Boutwells of this world.” Their meetings at the L&M Cafe had begun when Anderson, as a first assistant DA, would accompany Walsh whenever the district attorney sat down with Boutwell for one of their regular coffees. Among the topics at hand was no doubt the Lucas case, which Walsh and Anderson had prosecuted. When Walsh stepped down, in 1985, to run for higher office, Anderson was appointed district attorney by Governor Mark White. He had been DA for little more than a year when Christine was murdered. Just 33, he had never run for public office before. Winning a conviction in the Morton case, which was front-page news, would become one of the new district attorney’s signature achievements. In the decades that followed, Anderson often cited the case in interviews and in his own writing when he reflected back on the high points of his 22-year career as a prosecutor.

Yet even with his strong allegiance to the sheriff, Anderson expressed reservations about the evidence early on. Boutwell had been ready to arrest Michael within a week of the murder, but it was Anderson who had held him off. (“I wanted to make sure, dadgum sure, everything was right on this case before we went out and arrested the guy,” Anderson would later tell Judge Lott during the trial.) According to Kimberly Dufour Gardner, a prosecutor who worked in the DA’s office in the mid-eighties, Anderson had voiced his doubts even after Michael’s arrest. “Mr. Anderson made a remark relative to Sheriff Boutwell arresting Morton so soon,” Gardner stated last year in a sworn affidavit. “I recall that he said he did not feel confident about the evidence against Mr. Morton at that time.”

After his arrest, Michael spent a week in the county jail in Georgetown before he was finally released on bond in early October. He returned home and tried to resume a normal life with Eric, who had been cared for by both sets of grandparents in his absence. Normalcy, of course, was impossible: in less than five months, he would be standing trial for the murder of his wife. Still, Michael continued working forty hours a week at the Safeway (the grocery chain’s union held that members could not be fired unless they were actually convicted of a crime), and he attended to the innumerable responsibilities of single parenthood, driving Eric to therapy sessions and cardiologist appointments. He knew that some of his co-workers didn’t know what to make of him, but others, like Mario Garcia, welcomed him back. The two men had not known each other particularly well before Michael’s arrest—they had never socialized outside of work before—but Garcia, who had let Michael into the Safeway on the day Christine was murdered, had always been certain that he was innocent. “That morning, he was the same as he always was,” Garcia told me. “I never doubted him. After everything he did to make Eric well, why would he leave him at a crime scene? Why would he kill Christine and then say, ‘And to hell with my son’? It didn’t add up.”

The notoriety of the crime followed Michael wherever he went. Strangers who had read about the case in the newspaper slowed down as they drove past the house. Teenagers cruised by at night, sometimes whistling and honking and making a scene. Michael had decided to sell the house shortly after the murder, and he put it on the market for a song, but there were no takers. One day, a customer approached him in the Safeway. “Hey, I heard that that guy who killed his wife works here,” the man said, lowering his voice. “Which one is he?”

During those months leading up to Michael’s trial, sheriff’s deputies regularly stopped by the Gee house to speak to Elizabeth, who was still recovering from having discovered Christine’s body. Her husband, Christopher, became accustomed to returning home from work to find a squad car parked out front. “She was home all day, next to where the murder happened, and she was scared to death,” he told me. (The Gees are now divorced, and Elizabeth did not respond to requests for an interview.) “Sheriff’s deputies would stop by our house while they were patrolling the neighborhood, and they would fill her head with these whacked-out theories about Mike dealing drugs and stuff that was way out in the ozone,” he said. “They scared the tar out of her. They kept telling her, ‘You need to be careful. You don’t know what this guy is going to do.’ ” By then, Christopher told me, it was clear that Elizabeth’s testimony would be part of the prosecution’s case; she not only had discovered Christine’s body but also had overheard some of Michael’s less charitable comments to his wife. Kept on edge by frequent visits from sheriff’s deputies, she would prove to be a powerful witness.

Though Michael had never been a demonstrative person, his stoicism and his apparent lack of sentimentality for Christine only fed Elizabeth’s anxiety. She was astonished to see him two days after Christine’s funeral using a Weed Eater to cut down the marigolds at the end of his driveway, which she knew Christine had planted over his objections. It did not matter that the flowers had already withered in the summer heat or that Michael had been sprucing up the landscaping to attract prospective home buyers; within the context of a murder investigation, cutting down the marigolds took on a sinister dimension. So did another, far stranger thing he did. After a friend who worked in construction cleaned and repainted the master bedroom, Michael resumed sleeping there, on the water bed where Christine was killed. (“I have happy memories of this bed too,” he told a horrified Marylee.) He was clearly still in a state of shock; he had also started keeping a pistol-grip shotgun beside him while he slept. But taken together, the marigolds, the bed, and the caustic remarks he used to make to Christine all hardened perceptions that he was callous and unrepentant and no doubt capable of murder.

According to Bayardo’s revised time of death, Christine could not have died after 1:30 a.m.

Cementing that view was the decision of Travis County medical examiner Roberto Bayardo, who had performed Christine’s autopsy, to change the estimated time of death. (Bayardo had previously worked with Boutwell and Anderson on the Orange Socks case.) Originally, based on his belief that she had eaten dinner as late as 11 p.m., Bayardo had found that Christine could have died as late as 6 a.m., a half hour after Michael left for work. But the medical examiner would later testify that he made that determination when “I didn’t know all the facts. I didn’t know when she had her last meal.” Bayardo changed his estimate shortly after Boutwell and Anderson visited the City Grill and retrieved a credit card receipt showing that Michael had paid for their meal at 9:21 p.m. According to Bayardo’s revised time of death, Christine could not have died after 1:30 a.m.

This conclusion was based on an examination of her partially digested stomach contents, a notoriously imprecise method for determining the time of death that was not recognized, even 26 years ago, as sound science. Bayardo’s math also defied logic; although the time that the Mortons’ dinner ended had been revised by less than two hours, he had adjusted the estimated time of death more dramatically, by nearly five hours. Still, his conclusion was crucial to the state’s case: besides Eric, the only person who had been with Christine between 9:30 p.m. and 1:30 a.m. was Michael.

Years later, Bayardo testified in the cases of two wrongfully accused defendants outside Williamson County who were eventually freed after evidence pointed to their innocence: Anthony Graves, who was sentenced to death in 1994 for murdering six people in Somerville, and Lacresha Murray, who was convicted of the 1996 fatal beating of a two-year-old girl in Austin. A 2004 assessment on appeal of Bayardo’s methodology in the Morton case by noted forensic pathologist Michael Baden, the former chief medical examiner of New York City and a preeminent expert in his field, would indicate that the medical examiner’s work was deeply flawed in this instance as well. According to Baden, Bayardo did not have critical data that would have allowed him to make a more reliable evaluation. “My review reveals a number of serious mistakes in the methodology used by the medical examiner,” wrote Baden in a sworn affidavit. “No proper observations were made at the scene of death of rigor mortis, livor mortis, or algor mortis—the stiffening of the body, the settling of the blood, or the body’s change in temperature—which are the traditional measures that assist forensic pathologists in determining time of death.”

Just weeks after Bayardo changed his time-of-death estimate, Anderson, who had expressed reservations about the strength of the state’s evidence, felt confident enough about the case to present it to a grand jury. And when the hearing was convened, Boutwell was the only witness he called. Based on his testimony, the grand jury indicted Michael for first-degree murder. At trial, Anderson would lean heavily on Bayardo’s conclusions to bolster the state’s case. The district attorney would even go so far as to have Christine’s last meal prepared and delivered to the courtroom for the jury’s inspection.

Bill Allison, one of Michael’s attorneys, told me that until Bayardo’s revision, “the evidence was weak. His finding changed everything.”

On February 10, 1987, the morning that The State of Texas v. Michael W. Morton got under way, Michael put on a suit, kissed his son on the forehead, and handed the boy to his mother, Patricia, who had come from Kilgore with his father, Billy, to help out during the trial. Michael had not boxed up any of the belongings that filled the four-bedroom house or made arrangements for Eric’s care in the event that he was convicted; given the lack of evidence against him, he felt cautiously optimistic that twelve people would not be able to find him guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. He drove his pickup to the home of Allison’s law partner, Bill White, an ex-Navy man and former prosecutor. White’s blunt, outspoken style complemented the more cerebral Allison, a clinical law professor at UT. When Michael arrived, White—who was busy poring through his notes—tossed him the keys to his Porsche and told him to drive. A quiet scene greeted them when they arrived at the Greek Revival courthouse on Georgetown’s main square. The crush of media attention would come later; on the first day, only a few reporters showed up.

In preparation for trial, Ken Anderson had immersed himself in the details of the case. The district attorney knew he was up against formidable opponents: both defense attorneys had impressive track records, and Allison had been one of Anderson’s own law professors. Addressing the five-man, seven-woman jury that morning, the district attorney laid out the state’s theory of the case, arguing that on the night of his birthday, Michael had worked himself into a rage after Christine rejected his advances. “He had rented a videotape, a very sexually explicit videotape, and he viewed that sexually explicit videotape, and he got madder and madder,” Anderson said. “He got some sort of blunt object, probably a club, and he took that club and he went into the bedroom . . . and he beat his wife repeatedly to death.” Anderson went on to explain that Michael had staged a burglary afterward to cover his tracks, though he had done a poor job of it, pulling out only four dresser drawers and emptying them. “He also decided he would write a note as if his wife was still alive,” Anderson continued. “So he wrote a note, pretending she was still alive, and left that in the bathroom.” The motive was a stretch—how often do husbands bludgeon their wives to death for not wanting to have sex?—but Anderson pressed on, telling the jury that Michael had taken Christine’s purse, his .45, and the murder weapon and disposed of them before showing up to work.

In the absence of any concrete evidence, Anderson relied on his most emotional material, calling as his first witness Rita Kirkpatrick, who haltingly provided a few facts about her daughter’s life. She was followed by Elizabeth Gee, who painted a portrait of an unhappy marriage. She told the jury of the Mortons’ frequent arguments and how she once heard Michael bark, “Bitch, go get me a beer.” She vividly described finding Christine’s body and how aloof Michael had been in the weeks that followed. When Anderson asked her to recount what he had done two days after Christine’s funeral, Elizabeth became emotional; she paused for a moment to collect herself, then looked at Michael. “Weed-Eating her marigolds,” she said, enunciating each word. Though much of Elizabeth’s testimony had felt “almost rehearsed,” jury foreman Mark Landrum told me, her disgust for Michael in that moment had been palpable. “From that moment on, I didn’t like Michael Morton,” Landrum said. “I’m assuming the entire jury felt that way too. Whether he was a murderer or not was still to be determined, but I knew that I did not like him.”

As he sat at the defense table weeping, Michael was grasping the full horror of what had happened to his wife.

Building on the idea that Michael hated his wife, Anderson also cast him as sexually deviant. Over the protests of the defense, Judge Lott allowed the district attorney to show jurors the first two minutes of Handful of Diamonds, the adult video that Michael had rented, under the pretext that it established his state of mind before the murder. Though tame by today’s standards, the film did not curry favor with a Williamson County jury. “I was repulsed,” Lou Bryan, a now-retired schoolteacher who served on the jury, told me. “I kept thinking, ‘What kind of person would watch this?’ ”

Anderson’s portrait of Michael only darkened after DPS serologist Donna Stanley testified that a stain on the Mortons’ bedsheet contained semen that was consistent with Michael’s blood type. (In fact, later analysis detected both semen and vaginal fluid, corroborating Michael’s account to Boutwell that he and Christine had had sex the week before she was killed.) Anderson used Stanley’s testimony to suggest an appalling scenario: that after beating his wife to death, Michael had masturbated over her lifeless body.

The burden on the state to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Michael had killed Christine was arguably lessened once he was cast as a sadist. Viewed through that lens, Michael was doomed. When he broke down as Anderson held up a succession of grisly crime-scene photos, his reaction was seen not as an outpouring of grief but as the remorse of a guilty man. “I felt like he was crying over what he had done,” Landrum told me. In fact, as he sat at the defense table weeping, Michael was grasping the full horror of what had happened to his wife.

Though the case remained entirely circumstantial, Anderson provided enough details to make Michael appear culpable. William Dayhuff, the husband of Christine’s boss at Allstate, took the stand to say that he remembered Michael carrying a billy club in his pickup for protection when he worked nights cleaning parking lots after-hours. Having introduced the existence of a potential murder weapon, Anderson then called Bayardo to the stand to provide testimony that would, in effect, place Michael at the scene of the crime. Bayardo told the jury that Christine had died within four hours of eating her last meal, though he added that his estimated time of death was an opinion based on his experience and “not a scientific statement.” (When Bayardo was asked in 2011 to clarify what he had meant by this, he said under oath that his estimate was “not based on science, real science.”) It was a subtle distinction lost on the jury, who naturally viewed Travis County’s chief medical examiner as a credible source for scientific testimony.

At lunchtime each day, when the courtroom emptied for an hour-long recess, Michael hung back, too unsettled to eat. The windows of the old, drafty courtroom afforded a view of Georgetown’s main square, and he often stood by them, staring down at the people below who casually went about their business. He marveled as they walked to their lunch appointments or waved at friends, unencumbered by anything like the terror that had begun to creep into his mind that he might actually be found guilty.

His attorneys also seemed more anxious, often forgoing lunch to study documents in preparation for the afternoon’s witnesses. But they were hampered by what they did not know. During the discovery phase that preceded the trial, Anderson had disclosed only the most rudimentary information about the investigation. He had turned over the autopsy report and crime-scene photos but fought to keep back virtually everything else, even the comments Michael had made to Boutwell and Wood on the day of the murder. “I’d never heard of a prosecutor withholding a defendant’s oral statements from his own attorneys,” Allison told me. “This was a degree of hardball that Bill and I had never encountered before.”

He marveled as they walked to their lunch appointments or waved at friends, unencumbered by anything like the terror that had begun to creep into his mind that he might actually be found guilty.

What Allison and White did have on their side was a Texas statute that required law enforcement officers to turn over all their reports and notes once they took the stand. However, when Boutwell climbed into the witness box on the third day of the trial, he produced fewer than seven pages of handwritten notes—notes which represented, he said, along with a brief report he failed to bring with him, all of his documentation on the case. “This was a major homicide investigation, and there was nothing there,” White told me.

Stranger still, Boutwell would be the state’s final witness. Anderson never called Wood—who had identified himself at a pretrial hearing as the case’s lead investigator—to the stand. It was a mystifying decision by the prosecution. “We smelled a rat, but we didn’t know what the nature of the rat was,” White said. “There were lots of reasons why Anderson might have decided not to put Wood on. Maybe he was a lousy witness who would get tripped up on cross-examination, or maybe Anderson was setting us up, trying to get us to call Wood, even though he was an adverse witness.”

There was another possibility as well. By not asking Wood to testify, the state was not obligated to turn over his reports or notes (though by law, the state was required to disclose any exculpatory evidence). With the limited information they did have, Allison and White mounted a vigorous defense, calling expert witnesses who cast serious doubts on Bayardo’s time-of-death estimate. But unlike the prosecution, they did not have a cohesive story to tell. As for who had killed Christine, Allison admitted to the jury, “We can’t answer that question because we don’t know.” He and White wove together the available facts they had—the unidentified fingerprints, the unlocked sliding-glass door, the footprint in the backyard—to suggest that an unknown intruder had attacked Christine. But without access to Wood’s notes, they were unable to see the whole picture. They did not know about the reports of a mysterious green van behind the Morton home, and they failed to understand the importance of the discarded bandana with a blood stain on it that had been recovered approximately one hundred yards away from the crime scene. Ultimately, neither Allison nor White would make mention of it during the trial. Nor did they bring up the frightening question that Eric had asked Michael about the man in the shower. The two attorneys knew that Eric had been home at the time of the crime and might have seen something, but they also knew the chances that Lott would allow a three-year-old to testify were slim, and they worried that Michael would object. “Michael was very protective of Eric,” Allison told me. “We were not allowed to talk to him about the case.”

When Michael himself took the stand on the fifth day of the trial, he calmly and steadily answered the questions that were posed to him, but he did not betray the sense of personal devastation that might have moved the twelve people who would render a verdict. “During this whole ordeal, he never fell apart,” Allison told me. “He wanted people to see him as strong. And I think in the end, that very trait worked against him.” Jurors were put off by his perceived woodenness on the stand. Landrum explained, “I would have been screaming, ‘I could never have done this! I love my wife!’ ” Bryan was not persuaded by his testimony either. “He just did not come off as genuine, because there was no emotion there,” she said.

Instead, it was Anderson who turned in the histrionic performance. At one point tears streamed down his face as he addressed the jury, and he shouted so loudly during his cross-examination that people waiting in the hallway outside the courtroom could hear him.

“Isn’t it a fact that you . . . took that club and you beat her?” Anderson cried.

“No,” Michael replied.

“And you beat her?” Anderson said, bringing his arms down forcefully as if he were using a bat to strike Christine.

“No.”

“And you beat her?” said Anderson, again bringing his arms down.

“No,” Michael insisted.

“When you were done beating her, what were you wearing to bed?”

“I didn’t beat her.”

“What were you wearing to bed?”

“Nothing.”

“Nothing on? And when you got done beating her, you masturbated?”

“No.”

“. . . And you took your dead wife’s blood while you were beating her and splattered it on your little boy’s picture, didn’t you?”

“No,” Michael said, his voice breaking.

During closing arguments, Anderson recast some of his shakiest evidence as ironclad proof of Michael’s guilt.

During closing arguments, Anderson recast some of his shakiest evidence as ironclad proof of Michael’s guilt. Echoing his cross-examination of Michael, Anderson suggested that the billy club was not just a weapon he had once owned but the instrument he had used to “beat her and beat her and beat her.” Bayardo’s time of death—which the medical examiner had qualified as an opinion, not scientific fact—became incontrovertible truth. “Medical science shows this defendant killed his wife,” Anderson told the jury, referring to Bayardo’s testimony. “The best [that] medical science can bring us shows this defendant is a killer.” (He used the term “medical science” a total of seven times.) Allison and White gave impassioned closing arguments that sought to persuade jurors that the state had not proved its case, but in the end, it was Anderson’s view of Michael—“He is remorseless. He is amoral. He is beyond any hope,” the district attorney would say—that overshadowed the slightness of the evidence against him. The jurors deliberated for less than two hours, though eleven of them were ready to convict at the start. “I was certain of his guilt,” Landrum told me.

As the guilty verdict was read, Michael’s legs went weak, and he had to be supported by one of his attorneys. Finally, he fell back into his chair, rested his head on the defense table, and wept. “Your Honor, I didn’t do this,” he insisted before he was sentenced to life in prison. “That’s all I can say. I did not do this.”

The trial had lasted six days. Allison—who would be haunted by the verdict for years to come and eventually go on to found the Center for Actual Innocence at UT Law School—lingered after Michael was led away in handcuffs. Both he and prosecutor Mike Davis, who had assisted Anderson during the trial, stayed behind to ask the jurors about their views of the case. It was during their discussions in the jury room that Allison says he overheard Davis make an astonishing statement, telling several jurors that if Michael’s attorneys had been able to obtain Wood’s reports, they could have raised more doubt than they did. (Davis has said under oath that he has no recollection of making such a statement.) What, Allison wondered, was in Wood’s reports?

With his hands shackled in his lap, Michael looked out the window of the squad car and watched as the rolling farmland east of Georgetown gradually gave way to the piney woods of East Texas. Two Williamson County sheriff’s deputies sat in the front seat, exchanging small talk as they sped down the two-lane roads that led to Huntsville. Michael had, by then, spent a little more than a month in the county jail waiting to be transferred to state custody. During that time, he had gotten to know several county inmates who were well acquainted with the Texas Department of Corrections. They had given him advice he never forgot: keep your mouth shut and your eyes open, and always fight back. In prison, it didn’t matter if you won or lost. In the long run, getting the hell beaten out of you was better than showing that you were too scared to fight.

When they reached Huntsville, the deputies deposited him at the Diagnostic Unit, the intake facility where he would spend the next several weeks before being assigned to a prison. Once inside, he was ordered to strip naked. His hair was sheared and his mustache was shaved off, leaving a pale white stripe above his upper lip. He was issued boxer shorts and ordered to get in line to pick up his work boots. As he waited, Michael studied the man in front of him, whose back was crisscrossed with scars—stab wounds, he realized, as he counted thirteen of them in all. Michael was herded along with the other inmates into the communal showers and then to the mess hall, where they gulped down food as a prison guard shouted at them to eat faster. At last, when the lights shut off at ten-thirty, Michael lay down in his bunk, a thin mattress atop an unforgiving metal frame. Sporadically during the night, he could hear inmates calling out to one another, imitating different animal sounds—a rooster crowing, a dog baying—that reverberated through the cell block.

Even then, as he lay in the dark listening to the cacophony of voices around him, Michael felt that he would be vindicated someday. He just didn’t know how or when that day would come.