Prologue

Every murder involves a vast web of people, from the witnesses and the detectives who first come to the scene, to the lawyers and the juries who examine the facts, to the families of the victims, who must make sense of the aftermath. The more traumatic the killing, the more intricate the web. In the summer of 1982 the city of Waco was confronted with the most vicious crime it had ever seen: three teenagers were savagely stabbed to death, for no apparent reason, at a park by a lake on the edge of town. Justice was eventually served when four men were found guilty of the crime, and two were sent to death row. In 1991, though, when one of the convicts got a new trial and was then found not guilty, some people wondered, Were these four actually the killers? Several years after that, one of the men was put to death, and the stakes were raised: Had Texas executed an innocent man?

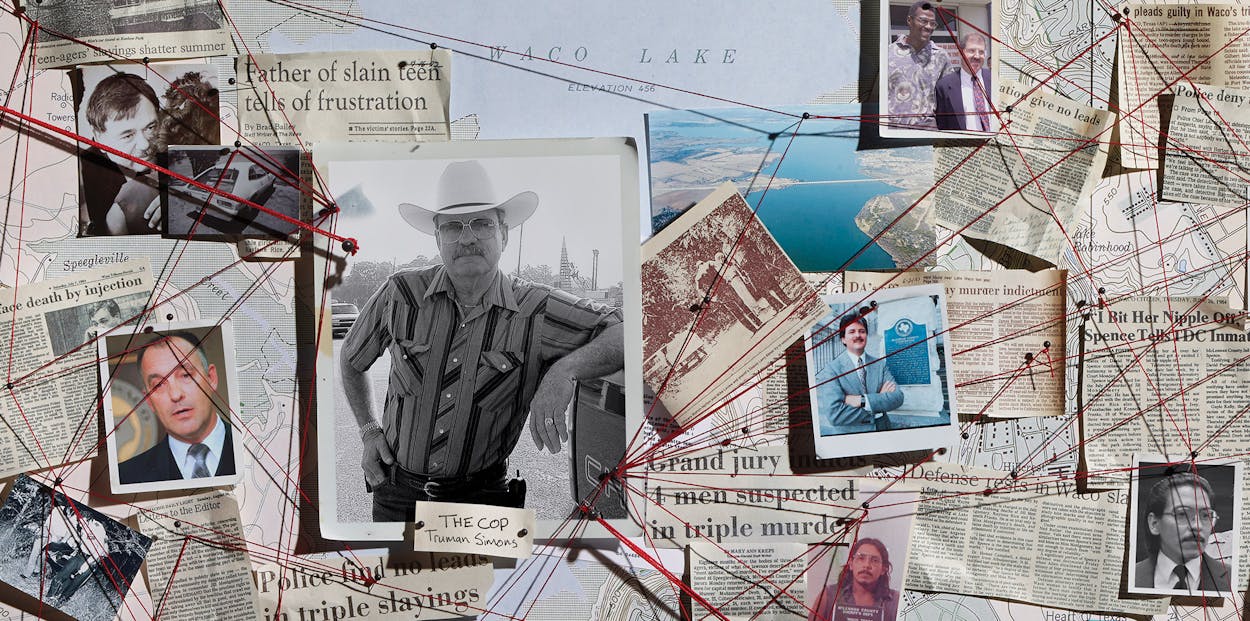

This story examines the case through the viewpoint of five people: a patrol sergeant who investigated the crime; a police detective who became skeptical of the investigation; an appellate lawyer who tried to stop the execution; a journalist whose reporting has raised new doubts about the case; and a convict who pleaded guilty but now vehemently proclaims his innocence.

A word about the reporting. This article is the result of a full year of research—dozens of interviews were conducted with the principal and minor players, and thousands of pages of transcripts, depositions, and affidavits, from the case’s six capital murder trials and one aggravated sexual abuse trial, were carefully reviewed. Still, what follows is not a legal document; some of the people involved in the case are dead, others don’t remember much, and even others—including the patrol sergeant who investigated the case and the DA who prosecuted it—refused to be interviewed. What follows is a story, built around the question that has haunted so many people for so many years: What really happened at the lake that night?

I. The Cop

Patrol sergeant Truman Simons was driving down Franklin Avenue, in downtown Waco, when the call came over the police radio. It was around six-thirty on a summer evening in 1982, and the 39-year-old officer had just returned to his squad car after visiting his wife, Judy. His shift, from three p.m. to one a.m., didn’t allow the couple to see much of each other, so he’d stop by her office when he could, then head back out on patrol. Now it was dinnertime, and Simons had been thinking about grabbing some food, maybe at the Whataburger over on Seventh.

The call was urgent: a body had been discovered at Speegleville Park, near Lake Waco. Simons, a ruggedly handsome man with dark-brown eyes and a brown mustache, took a deep breath. Waco had been having a violent summer; it was July 14, and already a dozen people had been murdered in the city of 100,000. Some cases were the kind he’d seen before, like that of a prostitute who’d been stabbed and thrown into the river. But others had left even the most hardened officers in the Waco Police Department reeling. Just ten weeks earlier, a father of five had been beaten to death by a stranger in his front yard because he wouldn’t light the guy’s marijuana cigarette. In June two cops had been shot in a gun battle downtown. For all of Waco’s small-town feel, Simons—himself the father of a young boy—recognized that these were big-city problems.

Simons knew Waco well. He had grown up in Rosenthal, a tiny town just south of the city, and joined the WPD in 1965, a few years after dropping out of high school. He hadn’t really intended to become a cop, but once on the force, he found the work to be a calling, and over his seventeen-year career he’d covered every inch of Waco, leading both the narcotics and tactical squads. “I’m just an old country boy,” he would say, but behind his self-deprecating manner were a sharp intellect and an insatiable drive for justice. Over time, many of his peers had gravitated to desk jobs, but Simons remained committed to the streets. It was there, he felt, that he could actually solve crimes, often using a network of informants he had carefully developed over the years. On the streets he could also stay away from the politics and backbiting within the police department, which at times had made him consider quitting. He was a man who liked to work alone, following his gut instincts; he’d worked the streets long enough now to have seen many of his hunches proved right. Though he wasn’t a regular churchgoer, Simons felt God’s hand in his work, and he often quoted from the Book of Matthew: “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called the sons of God.”

Simons turned his patrol car around and headed for Texas Highway 6 and the Twin Bridges that spanned Lake Waco. He’d driven that road many times, and as he crossed the reservoir, he looked out over the water. Waco didn’t get much credit for physical beauty, but this lake, just inside the city’s western border, was a jewel, deep and blue. It had been created in 1930, when engineers dammed the Bosque River, and now there were six parks along its edges, with pretty white-sand beaches. Speegleville was the largest, a pleasant, wooded wilderness that made for good camping, hiking, and fishing.

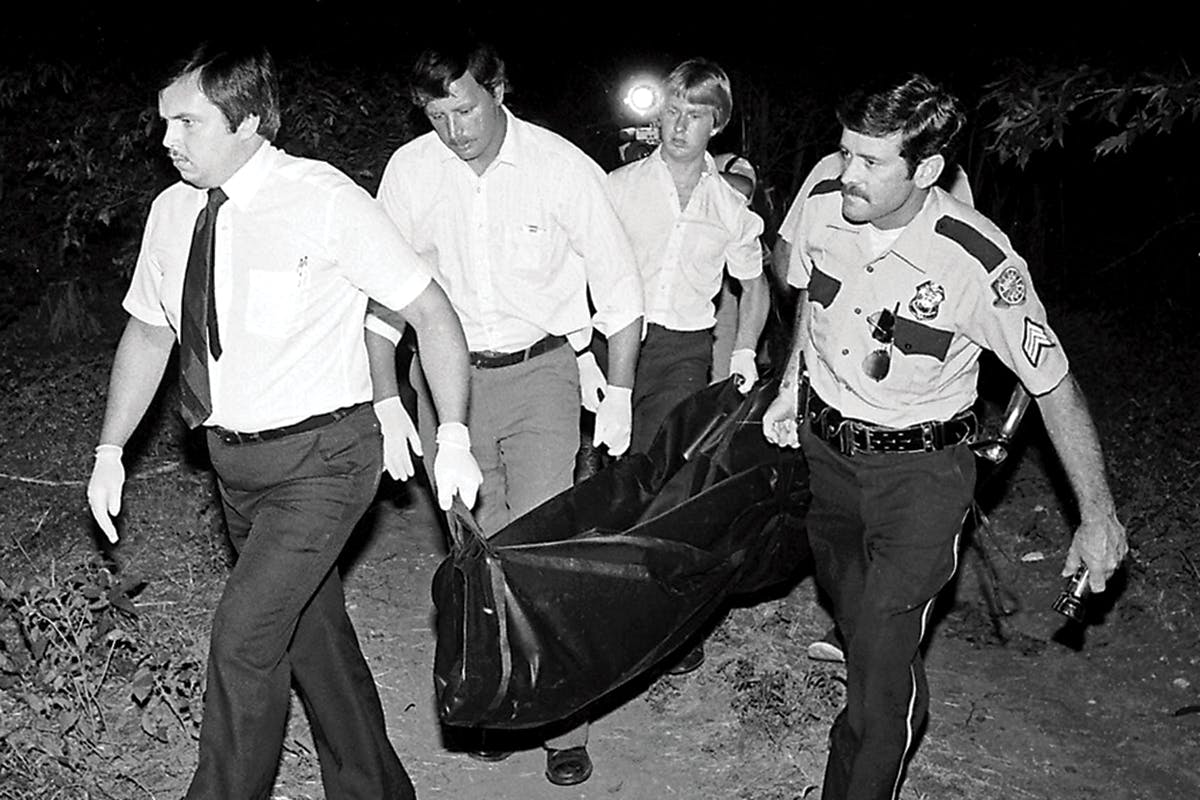

At the park entrance, Simons met a couple of other policemen and some sheriff’s deputies. Together they drove into the park, heading down a rutted dirt lane that snaked through the brush, until they came to a lonely fork in the road at the edge of the woods. A crowd of deputies from the sheriff’s and constable’s offices stood around talking; several reporters milled about as well. Simons parked and made his way to one of the deputy constables, who pointed out two young men standing nearby. They had been looking for a place to fish when they’d spotted the body near the foot of a tree, lying beneath some low-hanging branches. Thinking that it was a prank—a mannequin, perhaps—or that maybe they’d come across a sleeping drunk, they’d stopped to investigate. But their curiosity had quickly turned to horror: a young man, in jeans and an orange shirt, lay gagged, his hands bound behind him. His shirt was stained with blood, his chest full of stab wounds.

The sergeant got on his hands and knees and crawled under the branches. The victim, he could see, was just a boy, with a wispy mustache. He wore a pair of half-tinted aviator glasses, which were slightly cocked on his face. As Simons stood up, WPD detective Ramon Salinas showed him a photograph of an eighteen-year-old named Kenneth Franks, who had been reported missing earlier that day. The dead boy was clearly Kenneth, the men agreed, studying the photo. But there was more, said Salinas. Kenneth had last been seen with two girls from Waxahachie, a blond seventeen-year-old named Raylene Rice and a brunette seventeen-year-old named Jill Montgomery. They too were missing.

Simons felt uneasy. Nobody seemed to be in charge of the crime scene yet, so he took command, instructing the deputies and cops to fan out and search the area. Within minutes, a cry arose from about 75 feet away. Simons hurried over. Lying in the grass was the body of a young blond woman. She had been stabbed repeatedly and was naked except for a bra that was tied around her right leg. She was gagged, her hands bound behind her back. Heart pounding, Simons peered around the immediate surroundings. He and his fellow officers soon spotted something else: a bent knee, rising above some weeds. It belonged to another young woman, this one dark-haired. She had been stabbed multiple times and was naked, gagged, and bound. Her throat had been slashed. She still had on a Waxahachie High School class ring. They had found Raylene and Jill.

None of the officers on the scene had ever encountered a crime this grisly. The teens had been bound with shoelaces and strips of towel and stabbed a total of 48 times. Many of the wounds were shallow, suggesting they had been tortured. “I’ve seen a lot of gory things,” Salinas later told a Waco reporter. “Guys getting their faces shot off. But that didn’t bother me like this.” The murders, another official said, were “the most sadistic” and “cruel” he had seen in his career. Simons, walking among the bodies as he searched for clues, was shaken. Who would do something like this? And why? On instinct, he kept returning to Jill, who he sensed had been the main target. Standing over her, he felt overwhelmed by the evil that had befallen her.

Simons crouched down next to her lifeless body. “I don’t know what’s happened to you,” he whispered in her ear, “but I promise you one thing. Whoever did it won’t just go to jail—he is going to pay for this. I promise you that this won’t be another unsolved murder case in Waco, Texas.”

The next morning, citizens across Waco awoke to a terrifying headline. “Man, 2 Teen-age Girls Found Stabbed to Death at Lake Park: Police Say Bodies Bound, Girls Nude,” read the front page of the Waco Tribune-Herald. Local newscasts repeatedly showed images of ambulance workers and police officers, including Simons, carrying three body bags out from the brush. The youth and innocence of the victims—all three were high school students—made the crime particularly senseless. Fear spread through town, and residents began locking their doors at night and pushing for park curfews.

The case was quickly assigned to WPD lieutenant Marvin Horton, who headed up a special investigative force of seven full-time officers. For days, the department’s phones rang nonstop as people called in with leads, most of which amounted to nothing: someone claimed that members of a biker gang known as the Scorpions had bragged about the killings; someone else reported having given a ride to an “extremely nervous” man with blood on his pants who had been walking along a nearby highway on the morning after the bodies were found; one caller reported that someone had been doing “Indian rituals” near the crime scene; another said that there was a “devil’s cult” operating in the area.

Investigators learned that the girls had driven from Waxahachie, an hour north of Waco, in Raylene’s orange Ford Pinto to pick up Jill’s last paycheck from Fort Fisher, at the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum, where she had been a tour guide that spring. The girls cashed it at a supermarket and drove to Kenneth’s house. Jill knew Kenneth from the Methodist Home, in Waco, a boarding school for troubled and academically challenged kids; the two had lived there for a while and dated each other but were now just friends. Kenneth told his father that they were going to Koehne Park, which was directly across the lake from Speegleville Park. It was a spot where teenagers often congregated to drink, smoke, and hang out.

After that, however, the teenagers’ trail vanished. Though several people had seen them arrive at Koehne, and Raylene’s car was found there, no one had seen them leave. No one had heard any screams. Investigators couldn’t figure out how they’d gotten across the lake to Speegleville. There was no evidence of a boat, and there were no tire tracks around the Speegleville gate, which closed at eleven. A couple of Bud Light cans found near Raylene’s body yielded no fingerprints. The grass around the girls was flattened, as if they’d struggled with whoever killed them, but there was no knife, very little blood on the ground, and no semen anywhere—even though the medical examiner eventually determined that the girls had been sexually assaulted.

“It’s amazing the lack of information we’ve found out there,” Sergeant Dennis Kidwell told the Tribune-Herald. WPD officers combed the parks repeatedly and interviewed between 150 and 200 people, yet they found few clues and no discernible motive. “Nothing like this had ever happened in Waco,” Officer Dennis Baier would remember years later. “As a police department, we were totally unprepared for the complexity of this case.”

Simons in particular seemed to be deeply affected by the brutal scene he’d encountered. Though he was not officially assigned to the investigation, he spent hours at the lake, devoting much of his free time to searching the woods and talking to people. This didn’t surprise his fellow officers; it was this kind of dedication that had helped him solve difficult cases in the past. “When he got on the trail of something,” remembered Officer Richard Ashby, who patrolled the streets with Simons in the late sixties, “you couldn’t get him off.” Police chief Larry Scott agreed. “He would work like a bird dog, around the clock,” he recalled. Simons, a man of intuition, couldn’t always explain his methods, but everyone knew they got results. “I don’t know how he does it,” said one of his fellow officers around the time of the investigation, “and I don’t want to know.” (Simons declined to be interviewed for this story.)

Compelled by his vow to avenge the teenagers—he’d whispered the same promise to Raylene and Kenneth as he had to Jill—Simons kept tabs on investigators’ progress, even stopping by police headquarters after his shift to read their reports. He was especially baffled by the question of where the kids had been killed. In his long career, he had discovered that he could often feel the violence in the air at a crime scene—and later use that sense to connect the perpetrator to the deed. But he hadn’t felt any violence at Speegleville. These kids, he felt sure, had been killed somewhere else.

On September 9, Simons walked by Salinas’s desk and saw the case file lying out. Opening it, he read that there were still no definitive leads. The police had developed a few suspects, including Terry Lee “Tab” Harper, a local tough guy with a long record of assaults. They had also recovered a few hairs from the bodies of the teenagers. But the hairs did not implicate anyone in particular, and eight weeks into the case, there was simply not enough evidence to make any arrests. Though the WPD would continue to respond to new leads, the investigation, Salinas had written in the report, was now officially inactive.

Simons called Chief Scott at home. He had been working on the lake murders in his spare time, he told his boss, and he wanted permission to take over the case. Simons and Scott often had disagreements; in truth, the two men didn’t much care for each other, and the cop had already told the chief he was considering leaving the force at the end of the year. But Scott knew this case had to be solved. He was persuaded when Simons told him he had some new ideas. As Scott would later recall, Simons said he would solve the case in a week.

The next day, Simons pulled all the police reports that had been filed in the case and, with the help of Baier—whom Scott assigned to assist Simons—began looking for any leads that hadn’t been exhausted. Before long they found a tip from Lisa Kader, a seventeen-year-old who had lived at the Methodist Home with Kenneth and Jill. During an interview with investigators, she had fingered a man named Muneer Deeb, who she said didn’t like Kenneth and became angry at the mere mention of his name. Simons knew Deeb: he was a 23-year-old Jordanian immigrant who ran the Rainbow Drive Inn, a convenience store across the street from the home. He walked with a limp and went by the nickname Lucky.

Simons and Baier set out to investigate. There had indeed been bad blood between Deeb and Kenneth, they learned; Kenneth had shouted obscenities at Deeb inside his store, called him Abdul, and made fun of his limp. The source of the conflict, it appeared, was a sixteen-year-old Methodist Home resident named Gayle Kelley, who frequented the Rainbow Drive Inn and whom Deeb had offered a job. Deeb had an unrequited crush on Kelley, yet she was close with Kenneth. Such was the animosity between the two men, said several witnesses, that when Deeb learned of the murders, he laughed, saying he was glad Kenneth was dead.

For Simons, this was a promising start, and later that afternoon he and Baier sat down to interview Kelley, who had also been a friend of Jill’s. As Kelley, a slim brunette, answered their questions, Simons got a sudden hunch. He stopped Kelley mid-sentence. Had anyone ever told her, he asked, that she looked a lot like Jill? Yes, Kelley replied—in fact, people had asked if they were sisters. Baier didn’t see the resemblance, but Simons mentally filed the detail. That night, the officers got a huge break when a panicked Kelley called Simons at one in the morning. “He did it!” she screamed. “He did it!” After Simons calmed her down, she explained how, earlier in the evening, Deeb had taken her and a friend to a gory movie. Afterward, Deeb had confessed. “I did it,” he said. “I killed them.” Though he then apologized and said he was joking, Kelley felt certain he was not.

Simons phoned Scott with the news later that morning. Simons told the chief that Kelley had also said that Deeb was about to flee the state because the bank was foreclosing on his store. He needed to be arrested at once. Baier, however, wasn’t so sure. He, Salinas, Horton, and another investigator on the case, Sergeant Robert Fortune, didn’t believe there was nearly enough to make an arrest and were wary of Simons’ certainty. “He played things close to the vest,” Baier would explain later, “and that bothered some people.” Nevertheless, Scott, convinced of Deeb’s flight risk, approved the arrest, and that night Simons brought the store owner in for questioning.

Deeb loudly protested his innocence, claiming he knew nothing about the killings. Yet during his interrogation, Simons made another breakthrough. From the start, he’d felt that Deeb was too slight to have committed three murders on his own, and earlier he had followed up with the original tipster, Kader, to ask if she could think of any other suspects. Kader had mentioned a rough biker character known as Chili—his real name was David, she thought—who hung around the convenience store. Now, at police headquarters, Simons grilled Deeb about his acquaintances. Did he know a man named Chili? Yes, admitted Deeb; he often spent time at the Rainbow Drive Inn. When Simons took a break, Fortune—who’d been present for the interrogation—mentioned that he too knew Chili. His name was David Spence, and he had just been arrested with his friend Gilbert Melendez for cutting a teenage boy on the leg and forcing him to perform oral sex on Melendez.

A knife, a sex crime, a violent man: Simons was sure he was on to something. The next day he spoke with Jill’s mother, Nancy Shaw, and her aunt, Jan Thompson, and revealed a theory that was beginning to take shape in his mind. Kelley, he posited, had been the target of the killers. But in a case of mistaken identity, they had attacked Jill, and Raylene and Kenneth had been caught in the wrong place at the wrong time. When Simons then learned that, two weeks before the murders, Deeb had taken out an accident insurance policy on Kelley that paid $20,000 in the event of her death—and listed himself as Kelley’s common-law husband—he felt his instincts confirmed. Now there was a financial motive too.

“Truman thought Deeb would confess,” recalled Baier. “He really believed that.” Deeb’s family hired a lawyer, who pushed for a polygraph test, and after four days Simons agreed to set it up. After three hours of testing, the operator delivered his opinion: no deception. The results sent Simons into despair. Going into a separate office, he sat on the floor, absently tracing his finger on the carpet as he and Scott discussed what to do next. “He felt humiliated,” remembered Salinas.

To some of Simons’s colleagues, the results of the polygraph were no surprise. They had come to distrust the sergeant for his tendency to build cases on his own; in a vocation that valued teamwork, being a loner didn’t win him any friends. He seemed to prefer the company of hustlers to that of his fellow cops, and he was known among local law enforcement for his distaste for rules. (“You can put away the bad guys all you want, but you’ve got to do it right,” said a former investigator with the McLennan County DA’s office years later, recalling Simons’s work.) For his detractors in the WPD, Simons’s efforts to go after Deeb were evidence of his questionable methods and fixations. “You all just fucked up the whole goddamn case,” a disgusted Horton told Simons and Baier in front of a crowd of detectives the morning after Deeb was brought in.

But Simons knew he was on the right track, and he was going to see it through, skeptics be damned. (When Deeb’s lawyer asked him if the store owner was still a suspect, Simons retorted, “You bet your ass he’s still a suspect.”) He called the sheriff’s office and asked if there were any openings as a jailer. It would mean a cut in pay and status, but Simons didn’t care. He had a plan. David Spence was at the county jail awaiting trial for aggravated sexual abuse. If Simons had a job at the jail, he could get close to Spence and use him to solve the lake murders.

Simons’s plan had been forming ever since he’d first learned about Spence. Soon after his interrogation of Deeb, he’d headed over to the jail with Baier to meet the inmate. To his surprise, Spence was so friendly that they fell into easy conversation; Simons even told him he was quitting the force. Spence, unaware that he might be a suspect, offered to help the officers in their investigation. At the time of the murders, he’d been working at Burke’s Aluminum, next door to the Rainbow Drive Inn; his girlfriend, Christine Juhl, worked in Deeb’s store, and Spence had spent many hours there, hanging out and playing video games. Spence said he’d have Juhl ask around on the street about the murders.

Spence was the kind of criminal Simons knew well: rough, poor, and full of swagger. A middle school dropout with a fondness for beer, marijuana, and amphetamines, he had married at 16, become a father of two by 18, and divorced at 20. He’d robbed a Fort Worth convenience store with a hatchet at 21 and served fifteen months. By the time he got out of prison, he had become entranced by the biker lifestyle. He got tattoos: dice on his right arm, Harley wings on his left. Now 24, Spence had become more and more unpredictable and violent. But he was lonely at the jail. And he liked to talk.

Soon after Simons began his new job as a sheriff’s deputy, working the graveyard shift from midnight to eight, he and Spence began having regular conversations, often about the Lake Waco case, which the inmate clearly enjoyed discussing. Simons would allow him long phone calls to Juhl, sometimes until three or four in the morning, but she failed to turn up any new leads. Afterward, the two men would sit and talk—about life, love, God—sometimes until the sun rose. “I get people talking, and then I shut up and listen,” Simons would later explain. Spence’s lawyer in the abuse case, an earnest attorney just three years out of law school named Walter Reaves, had instructed his client not to speak to Simons, but Spence ignored him; when Spence’s father asked Simons if he should hire a lawyer for his son for the murder case, the deputy said Spence didn’t need one because he hadn’t been charged with murder.

Spence had, however, been informed that he was a suspect by then. Simons told him early in their relationship, a few weeks after arriving at the jail. Spence was caught off guard and hurt—hadn’t he been trying to help the investigation?—but he enjoyed his time with the deputy so much that he nevertheless continued their late-night discussions. Spence claimed he’d had nothing to do with the murders, but Simons bided his time, talking to other inmates and coming to the jail outside work hours.

In early January, the deputy’s patience paid off: an inmate named Kevin Mikel told him that Spence had bragged about killing the teenagers. Mikel gave Simons some corroborating details, such as how Kenneth had been bound with shoelaces and Raylene had had a bra tied around her leg; he also reported that Spence had suggested that Gilbert Melendez—Spence’s co-perpetrator in the abuse case—had been involved. Spence knew Melendez through his younger brother, Tony, with whom Spence had gone to school.

Before long, other inmates were also coming forward with things Spence had told them: he had been in a satanic cult; he’d been paid to kill the teens but had killed the wrong ones; a foreigner named Lucky had paid him to kill the three because a girl had dishonored him. Simons decided to share his findings with Waco’s new district attorney, Vic Feazell. A charismatic, headstrong lawyer, Feazell had stepped into office that month, at the age of 31. After campaigning on the promise to shake up a complacent DA’s office, he’d been elected in an upset, and he now set about hiring more prosecutors, tightening protocols for defense attorneys, and increasing security measures. (His office, outfitted with an elaborate taping system, was soon nicknamed Fort Feazell.) A Baptist preacher’s son who took to the pulpit himself on occasion, Feazell— married and with a son of his own—had promised that he would be active in the courtroom; his first trial as lead prosecutor, in fact, was to be Spence’s aggravated sexual abuse case.

Simons was sure the DA would be interested in his jailhouse findings, but when he approached one of Feazell’s assistants, he was told that, as hearsay, the inmate testimony was probably inadmissible in court. Simons was undeterred; he felt that his relationship with Spence was the key to solving the case. Spence had grown so dependent on their conversations that he would sometimes call Simons at home, waking him up to talk. At the jail, Spence had taken to pacing back and forth, crying hysterically after each marathon phone call with Juhl, despairing that she was about to leave him. Sitting calmly nearby, Simons would tell him to let it all out. When Juhl finally did break things off, Spence went so berserk he had to be given a shot of Thorazine. “The only friend I’ve got,” he told Simons that night, “is the guy who’s trying to kill me on this lake case.”

Spence seemed more and more bewildered about what was going on in his mind. The two men started discussing the idea that maybe, like Ted Bundy, Spence had a split personality, and Chili was his evil half. Spence insisted he couldn’t remember murdering anyone, but he began to wonder if it was possible that he had really done it.

“Did I kill them kids?”

“I think you did,” said the deputy.

“Why don’t I know?”

In early March Feazell announced that he was creating a task force to take a new look at the Lake Waco murders. Despite some qualms about Simons’s methods, he included the deputy on his team, along with the two cops most familiar with the case, Salinas and Baier. This made for an awkward arrangement, since Simons and the WPD officers had been on cool terms after he’d left the force. Baier and Salinas decided they’d focus on the rest of the city and leave the jailhouse world to their old colleague.

Simons, meanwhile, began to work on Gilbert Melendez. A tough 28-year-old from Waco who’d served time in the mid-seventies for assault with intent to murder, Melendez had been given seven years after pleading guilty in the aggravated sexual abuse case. (Spence was found guilty in late March and given ninety years; he was allowed to remain at the jail because he was helping with Simons’s investigation.) Melendez had always denied any involvement in the lake murders, but now Simons, encouraged by the headway he’d made with Spence, began to press the inmate. Things were about to get crazy, he said, and Melendez might want to consider talking. Melendez gave it some thought. Later that day, when Simons returned to see him, he had something to say. “I was out there,” he told the deputy. Simons informed him that if he confessed and testified against Spence, he’d almost certainly avoid the death penalty. “I’ll testify,” said Melendez.

Simons turned on a tape recorder as Melendez recounted the events of that night. He and Spence had been riding around in Spence’s car, he said, drinking and smoking, when they went to Koehne Park. There they’d seen the kids, whom Spence enticed into the car with the promise of beer and weed. Spence raped and stabbed Jill, then Raylene, and finally he killed Kenneth. He and Melendez drove the bodies to Speegleville and dumped them there. Then they went home.

It was just what Simons had been waiting for—a statement from an actual eyewitness. But as Baier soon pointed out, there was a problem: when asked for details on Spence’s car, Melendez had said it was a station wagon. Yet Spence hadn’t bought his station wagon until two weeks after the murders. Simons went back to the inmate, even taking him to Koehne and Speegleville parks the next morning; over two days, Melendez gave three statements that included other discrepancies, such as different times for when he and Spence arrived at Koehne Park. Simons thought the inconsistencies were likely due to Melendez’s drug- and alcohol-addled memory, but the changing statements, plus the fact that Melendez claimed it had been Spence alone who did all the raping and killing, made other investigators suspicious. Though Melendez took two polygraphs that seemed to confirm his involvement, he also recanted his confession entirely. He was sent to prison.

It was April 1983; in a few months, the local media would mark the one-year anniversary of the murders, and yet the investigation was still floundering. Then Simons got a surprise visit from Ned Butler, an assistant DA who had recently been hired to try capital cases. He gave Simons a cryptic message: soon, Butler said, he’d be able to tell the deputy whether his theory that Spence had killed the teenagers was correct.

Butler, it turned out, was a big believer in forensic odontology, or the study of bite marks. He’d made use of the discipline two years earlier to help solve a violent Amarillo murder in which the killer had bitten his victim. When Butler first saw the lake murders file, he immediately asked Salinas if they’d checked the bodies for bite marks. After studying the autopsy photos himself, he determined that several of the wounds on the girls’ bodies did, in fact, look as if they’d been made by human teeth. He had a mold taken of Spence’s teeth, then personally delivered it and the photos to Homer Campbell, a forensic odontologist in Albuquerque who had helped solve the Amarillo case. Within days, Butler got remarkable news: Campbell was certain that Spence’s teeth had made the marks.

At last, Simons had confirmation of what he had suspected all along. Even Feazell was won over. The task force now gathered momentum as investigators found witnesses who told of suspicious things Spence had said the previous summer: that he thought he had killed somebody, for example, and that he had raped two girls at the lake. More significant, the officers also had another suspect: Tony Melendez, Gilbert’s younger brother. A 24-year-old who was wanted in Corpus Christi for robbery and rape, Tony had been taken into custody by the WPD for questioning about the lake case and his brother’s involvement and then sent to the Nueces County jail. Though he insisted he had been in Bryan painting apartments the day of the murders, he failed a polygraph, and jailhouse informants claimed they’d heard him say he was at Lake Waco. That October, Feazell announced that his office was steadily putting together “a puzzle where someone is trying to hide some of the key pieces.”

One month later, the puzzle was finished. On November 21, 1983, a McLennan County grand jury indicted Deeb, Spence, and both Melendez brothers for the murders of the three teenagers. The DA’s office was exultant. “We started with nothing, and we have found pieces literally in the dark and fit them together,” a spokesman told the Waco Citizen. A grateful city breathed a sigh of relief. “We were finally going to hear the real story,” remembered Jan Thompson, Jill’s aunt. “We were finally going to find out what happened to our kids.”

The criminal trials for the lake murders were the most anticipated in Waco’s history. Throughout the spring of 1984, an endless string of pretrial hearings domi-nated the local papers; in nightly broadcasts, Waco’s citizens were regaled with details of the defendants’ shady pasts, including the rumor that Spence was a Satan worshipper. In April district judge George Allen made a decision: Spence would be tried first, followed by Gilbert, Tony, and then Deeb. Each man was charged with three counts of capital murder, and each would stand first for the killing of Jill Montgomery.

The run-up to Spence’s trial was particularly contentious. His lawyers, Russ Hunt and Hayes Fuller, were convinced their client was being railroaded—in their view, Spence’s long-running interrogation by Simons had been unorthodox, and the jailhouse testimony against him was suspect. Furthermore, although forensic odontology was admissible in court, there was no established science behind it, and allowing Campbell’s testimony would be a “travesty of justice,” argued the lawyers. After having their motions repeatedly denied by Judge Allen, Hunt and Fuller sent a 33-page letter to the FBI and the U.S. attorney’s office asking for help. “An innocent man has been charged with this crime and is very likely going to be convicted in state court and sentenced to death,” they wrote.

The lawyers’ pleas were ignored. Then, six days before Spence’s trial, they were dealt an even bigger blow: in an unexpected about-face, Tony pleaded guilty in exchange for a life sentence. It was yet another coup for Simons, who had visited Tony in jail until the inmate finally broke down. In a written confession, he stated he had participated with Spence and Gilbert in raping and killing the teenagers.

The trial began on June 18, 1984. Outside the majestic McLennan County courthouse, news crews set up cameras on the lawn; inside, the third-floor courtroom was jammed with spectators, who crowded into seats, stood in the aisles, and even sat on the floor. Relatives of the victims, including Kenneth’s and Jill’s parents, and friends who’d driven in from Waxahachie sat together with members of the DA’s office. (Raylene’s family chose not to attend the trial, and later they refused to comment on the case.) Everyone strained to catch a glimpse of the accused killer, who had gotten a haircut and wore a suit and tie. For Jill’s family, the day was especially excruciating. Her brother, Brad, who had refused her request for a ride to Waco on the day of her disappearance, was so distraught and full of rage that Simons feared he’d lunge at Spence as soon as he laid eyes on him; the deputy made him promise he’d behave himself. Jill’s mother, Nancy, who was scheduled to be a witness, had forced herself to study the crime-scene photos as a way of bracing herself for the gruesome details she’d hear in testimony.

The state’s case was based on the theory that Deeb had hired Spence and the Melendez brothers to kill Kelley for insurance money, but that Spence and the brothers had mistakenly killed Jill because she looked so much like Kelley. They’d killed Kenneth and Raylene to prevent them from talking. From the beginning, Feazell was a formidable prosecutor, calling 39 witnesses. “Evidence will show,” he declared, “that David Wayne Spence . . . not only bragged repeatedly that he was responsible for the murders but that he had details [about] how the murders were committed.” Seven jailhouse informants took the stand. One testified that he heard Spence say he’d bitten off one of Jill’s nipples; another stated that Spence told him that when he saw the teenagers, he’d said, “There’s the motherfucker that beat that Iranian on a drug deal. Let’s go get them and fuck them up.” Yet another claimed that Spence told him he had sexually assaulted the girls with a “whoopee stick.” The inmates denied receiving anything in return for their testimony. Several other witnesses reported the suspicious remarks Spence had made—about raping two girls at the lake, about being scared he might have killed someone. One testified that he had heard Deeb ask Spence if he knew of someone who could “get rid of” Kelley for a share of insurance money and that Spence had replied he could do it.

But the state’s case was entirely circumstantial until Campbell, the bite-mark expert, took the stand. Using electronically enhanced autopsy photos, the odontologist testified that Spence was “the only individual” to a “reasonable medical and dental certainty” who could have bitten the women. Hunt and Fuller promptly called their own expert, who said the quality of the photos was too poor to make a valid comparison. However, though he couldn’t say Spence was the biter, he also couldn’t exclude him. (The medical examiner said she had not recognized the bite marks at the autopsy, but she was now certain that some of the victims’ wounds had a pattern that sug-gested teeth.) Campbell’s words had a distinct impact. “We had life-size pictures of the marks and a cast of [Spence’s] teeth brought into the jury room,” remembered one juror afterward. “The testimony—‘everyone’s bite mark is different, like a fingerprint’—was very convincing.”

The defense tried its best. Hunt and Fuller pointed out that none of the hair or blood found at the crime scene tied Spence to the murders, and they insisted that Deeb had been joking about getting rid of Kelley and that Spence knew it. Besides, the lawyers argued, Spence knew Kelley, so the mistaken-identity theory made no sense. Hunt even got an insurance salesman to explain that Deeb’s insurance policy on Kelley was the kind often used to cover employees in case of accidents.

Still, the defense attorneys made a miscalculation in their overall strategy. They had hoped to introduce evidence showing that the crime could have been committed by two other men—James Bishop, a former Waco resident who had moved to California right after the murders and then been arrested for raping and attempting to kill two high school girls on a beach, and Ronnie Breiten, a man who had been seen in bloody clothes after a night fishing at the lake. But the judge ruled the evidence irrelevant to the case against Spence and refused to allow it.

The trial lasted just over two weeks. In his closing statement Feazell reminded jurors of the substantial testimony against Spence, the pain of the victims’ families, and the torture the teenagers had endured. “Folks,” he implored in the same preacher’s cadence he’d used throughout the trial, “it has been two years, and there are a lot of people who have been waiting for your decision.”

The twelve jurors found Spence guilty in less than two hours. As the verdict was read, Spence stared solemnly and a collective gasp went up from the courtroom. His mother, Juanita White, who’d attended every day of the trial, burst into tears. Three days later, Spence was given the death penalty.

“We feel the angels have been with us,” a fragile-looking Nancy told news reporters at the close of the trial. Afterward, when the crowds and cameras had dispersed, the jurors asked to meet Simons, about whom they had heard so much. Feazell brought him to the jury room. “Ladies and gentlemen,” he announced as Simons entered, “I thank God for men like Truman Simons. So should you.”

A week later, Simons felt like taking another look around the lake. He asked an investigator with the DA’s office to accompany him, and the two men wandered through Koehne Park. About 25 yards from the spot where Tony had said Jill was murdered, Simons was suddenly overcome by a strong feeling. He grabbed a stick and dug deep into the leaves. There, in the dirt, lay a gold bracelet.

Simons, who’d relied on his gut so many times before in his career, was stunned. Could the bracelet be Jill’s? He took it to the girl’s mother and aunt, who both said she had owned a bracelet like it. As the trials for Spence’s accomplices approached, the discovery seemed to be a sweet validation of all his work.

His tenacity, in fact, was about to pay off in other ways. Not long after Spence’s trial, Gilbert contacted the deputy; he had seen a news report on Spence’s getting hustled off to death row, and he now wanted to make a deal before his own trial. In January 1985 Gilbert wrote out a sixteen-page confession, pleaded guilty for two life sentences, and agreed to testify against Deeb.

Deeb’s trial, which began on February 25, lasted twelve days and featured forty witnesses, many of whom had testified against Spence, including one jailhouse informant. The ace in the hole, though, was Gilbert, who took the stand to describe the murders and stated that Spence had said Deeb would pay them $5,000 for killing Kelley. After closing arguments, in which Feazell likened the store owner to Judas Iscariot for his “dirty hands” in the killings, Deeb was found guilty in less than two hours. Like Spence, he was given the death penalty.

That October, a second trial for Spence—this time for Kenneth’s murder—was just as straightforward. Feazell didn’t have to rely as heavily on the murder-for-hire theory; thanks to Simons, he had new ammunition. There was the gold bracelet, entered now as conclusive evidence of where the teenagers had been killed. More important, Tony, in the expectation of getting help with parole, had agreed to give a more detailed statement and testify against Spence. On the stand, Tony told basically the same story as Gilbert, saying that he and his brother and Spence had killed the teenagers at Koehne and then loaded the bodies into Gilbert’s truck. The brothers’ testimony differed on some details—Tony said they’d partied for two hours before the violence began and that he stabbed Jill; Gilbert said the violence began almost immediately and that Tony stabbed Raylene—but they were consistent in their portrayal of a night characterized by beer, weed, and bloodshed.

Throughout the proceedings, Spence exhibited little of the calm he’d shown during his first trial. He was continually unnerved by Feazell, who seemed to enjoy provoking him: during jury selection, for example, as Spence’s lawyers questioned potential jurors, the DA passed him taunting notes (“You’re drowning and your lifeguards don’t swim!” read one). Spence, who had two new attorneys—Walter Reaves, who’d represented him on the aggravated sexual abuse case, and Bill Vance—grew increasingly agitated, eventually trying to fire his lawyers. “I know that we didn’t do this,” he cried out in exasperation at one point. “And I know that you know it too, Vic!” As before, the jury found him guilty. Again he was given the death penalty. “I’m really getting tired of this shit,” Spence whispered to his father, Edwin, before being sent to the Ellis Unit, outside Huntsville.

Feazell and Simons were hailed all over McLennan County as heroes. It had taken more than three years, but the tireless lawmen had finally brought the killers to justice. (With the four men safely behind bars, the DA chose not to prosecute further.) For Feazell in particular, the victory could not have come at a better time. Months before, in the spring, the DA had drawn nationwide attention when he cast doubt on the murder claims of famed serial killer Henry Lee Lucas. Feazell’s findings, which showed that Lucas lied about his victims, had embarrassed the Texas Rangers, who had used Lucas’ statements to erroneously clear dozens of murders. But as spring turned to summer, the limelight had grown dark: in June, Dallas television station WFAA ran a ten-part investigative series on Feazell and his office, accusing him of, among other things, dismissing DWI cases in exchange for money. Feazell had called the charges a “smear campaign” brought on by “the big boys in Austin” because of the Lucas case; now the convictions in the Lake Waco murders offered irrefutable proof of his commitment to the law.

Simons, meanwhile, became one of the most well-respected officers in the state. Two years later, he’d win a Texas Peace Officer of the Year award. He’d also be the featured protagonist in a best-selling book about the murders, Careless Whispers, which won the 1987 Edgar Allan Poe Award for fact crime book of the year. Despite this acclaim, Simons felt the most satisfaction from having fulfilled his calling. “I am a peacemaker,” he told the book’s author, Carlton Stowers. “I followed the direction that has been pointed out to me.”

He had one last gesture to make. Three years after her murder, Jill’s remains lay in an unadorned grave in a country cemetery just north of Waxahachie. The girl’s father, Rod Montgomery, owned a granite company and cut tombstones, but he had been so devastated by her death he had found it impossible to put up a marker. Now Simons, with the help of Stowers, ordered one and had it installed. The large, elegant slab of Dakota Mahogany granite was decorated by Jill’s mother with the girl’s photo, a poem, and the inscription “Forever Seventeen.” Not only had Simons kept his promise to avenge Jill, he had also made sure she would never be forgotten.

He could not have known that his promise, and every action he took to fulfill it, would shortly come under intense scrutiny—and, in the years to come, set the course for one of the strangest, most serpentine cases of criminal justice in modern Texas history.

II. The Detective

Jan Evans didn’t know anything about Waco before she moved there, in June 1981. An attractive blonde from Detroit, the 29-year-old thought the city’s name was pronounced “Wacko” and assumed its residents got around on horses. She was a tomboy who had grown up wanting to be a cop, like her grandfather, and joined the Detroit Police Department in 1977. But four years later she was laid off, and wanting to live someplace warm, she applied for a job in Texas. The Waco Police Department offered her a position, and when she arrived, she was pleasantly surprised to find that the city had cars and paved roads.

Evans threw herself into her job as a patrol officer; though she knew that many Southern cops believed police work should be reserved for men, her fearlessness and forceful attitude quickly earned her a reputation, in the words of Chief Larry Scott, as “one of the best officers we had in the department.” The Lake Waco murders, which took place a year after she arrived on the force, were a rude awakening. Evans had seen plenty of murder and mayhem in her career, but nothing this macabre. Though she didn’t take part in the investigation, she followed it avidly, and she was relieved when David Spence, Muneer Deeb, and Gilbert and Tony Melendez were finally put away.

Evans liked Waco. She found that the weather and the laid-back, friendly attitude of Texas suited her. She also fell in love with a fellow officer, J. R. Price, whom she married; the two bought some land out in the country and acquired a few horses. Evans changed her name to Jan Price, and after several dedicated years on the force, she became a detective.

Almost five months after the final conviction in the lake murders, at around noon on March 2, 1986, Price got a call about a questionable death at a house on North Fifteenth Street. It was a Sunday, and she had been working with one of her horses, but she was the on-call detective that week. J.R., who also got the call, was to serve as crime-scene investigator; taking separate cars, Price met him and Ramon Salinas at the address. There they found a footprint on the front door, which had been kicked in, and some smudged fingerprints around the house. In the back bedroom, facedown on the bed, lay the nude body of a 54-year-old woman. She had been raped, sodomized, beaten, and suffocated. Her name was Juanita White. She was David Spence’s mother.

White, the investigators learned, had gotten off work the previous night at nine-thirty, after her shift at Uncle Dan’s Barbecue, where she bused tables and washed dishes. When she didn’t show up for church the next morning, her Sunday school teacher stopped by the house and found her. White had struggled with her attacker—her nose was broken, her ear torn, her body battered. She also had marks on her skin that looked as if they’d been made by teeth. The contents of White’s purse were strewed across the floor, and her car was missing; the vehicle was found several hours later at an apartment complex about fifteen blocks away.

The crime struck Price as unbearably sad. White was poor and had had a hard life; she’d been married four times and had lived long enough to see her son vilified as a monster, only to die like this. To make matters worse, seven hours after the officers finished searching White’s home, they received a call to return to the scene: the house had been broken into again. The intruder had not taken anything of value—the TV was still there—but had ransacked the front bedroom, opening several boxes and scattering papers everywhere. The bedroom, Price discovered, had been Spence’s. “Somebody went in there looking for something,” she told me years later, recalling the strangeness of the case.

Price soon learned that White had been conducting her own investigation into the lake murders—going to bars and asking questions, interviewing figures in Waco’s demimonde, looking for evidence to prove that her son hadn’t killed the three teenagers. White had another son, Steve Spence, who told officers that she had begun to receive threats; she also thought her phone was tapped.

Price was astounded to find that a few days before her death, White had received a letter from Spence that had been sent to him by Robert Snelson, one of the men who had testified against him; he was the informant who told jurors that Spence had confessed to biting off Jill’s nipple. In his letter, Snelson wrote that he had made his testimony up. White rushed the letter over to Russ Hunt, Spence’s trial lawyer. “She was really excited,” he recalled. “She was sure it would result in her son’s exoneration.” Hunt, who still believed that Spence was innocent, made copies, one of which he sent to the U.S. attorney’s office. Leon Chaney, a private investigator who knew the case, remembered, “[White] called Hunt and me all the time; she was going to give us all these leads. On that Friday, she said, ‘I think I’ve found out what happened. I have a witness.’ ”

Two days later, White was dead. Price began to work the murder, but within days, she learned that someone—either from the sheriff’s office or the DA’s office—had been making calls to the Dallas County crime lab, where White’s body had been sent, to ask for the preliminary autopsy results. This was unusual; as far as Price knew, no one outside the WPD was on the case. Then, within a week, the DA’s office asked for all the police files on White. Vic Feazell was taking over the case and appointing Truman Simons as his investigator.

“I’d never heard of the DA getting involved so quickly in an investigation,” recalled J.R. “Two weeks into a whodunit like the White case, you’re just getting started.” Price would continue working the case for the WPD, but she felt blindsided, as if she had done something wrong. Other officers weren’t so surprised. They’d seen Simons take over an investigation before. (Simons has said that he got involved only after he received calls from a few of his informants.)

The rift between the WPD and Simons made Price nervous. She knew of the deputy’s reputation for relying on informants and had heard negative things about him from her fellow officers; as she would later say in a deposition, people arrested by the WPD “were getting right back out of jail because they were supplying information to Simons.” (Simons has always denied that he made deals with suspects, saying he didn’t have the power. As he testified in a deposition in 1997, “I’m a deputy sheriff, I’m not an assistant DA or a prosecutor. I don’t have the authority to do anything.”)

When Simons contacted Price, he told her that he already had a suspect. As soon as he’d heard about White’s death, he’d called Dennis Baier, who told him that a black man had been seen exiting White’s stolen car. Simons promptly put out feelers to his contacts on the street and got a name: Calvin Washington, a 31-year-old ne’er-do-well who, it turned out, had recently landed in the McLennan County jail for car theft. Simons had searched Washington’s sister’s apartment, where he had been arrested, and found a sweatshirt that appeared to have blood on it, as well as some tennis shoes whose treads Simons thought might match the footprint on White’s door.

The deputy had also heard—from other officers or his informants—that White had been bitten by her assailant, and so on March 17 he visited Washington in jail and asked for his permission to take a dental mold. (Simons would later say that it was Price who believed the wounds on White’s body were bite marks and that they agreed to get the mold after looking at autopsy photos together; Price insists that the mold already existed when she and Simons joined forces.)

Price was stunned that Simons had taken his investigation so far without her, but she agreed to accompany him to go speak with Jim Hale, a forensic odontologist in Dallas who was studying the Washington mold. She had been a detective for only two years at that point, and they were after a vicious killer. Perhaps Simons’s informants knew what they were talking about. Hale, at least, seemed to reassure her that Simons was on the right track. When the officers got to Dallas, he informed them that Washington’s mold matched the wounds on White’s body.

Simons told Price that, through his informants, he had learned that Washington had had a partner in crime, a nineteen-year-old named Joe Sidney Williams. When they returned to Waco, Simons set about gathering information on the young man, talking assiduously to sources both in and out of jail. Price continued investigating too, but she became increasingly frustrated with her partner. For one thing, Simons wasn’t filing any reports. “He didn’t want to tell you anything beyond ‘This is what I’ve got,’ ” Price told me. (Simons later testified that he didn’t file reports because the WPD and the sheriff’s office had different reporting systems and it would “mess up the statistics.”) And although Simons initially shared leads from his informants, Price told me that when she tried to corroborate their claims, several of them said Simons had instructed them not to talk to her. (Simons testified that he fully cooperated with Price.)

By mid-April, Price’s frustration had turned to suspicion of Simons’s techniques. As she would later testify, she had checked with the courthouse records and found out that many of the jailhouse informants were getting their cases dismissed by the DA’s office. Furthermore, in her view, the evidence that Simons had gathered was not very impressive—the blood on the sweatshirt, it turned out, was barely a drop, and the sneakers did not match the shoe print from the front door.

Then Price began to develop a different suspect. On May 1 a woman who lived a few blocks from White was violently attacked in her home. She was beaten with a hammer, raped, and left for dead. As in White’s case, the assailant had kicked in the door; he had also stolen her purse. The woman survived and identified her attacker, a young man named Benny Carroll, who had been dating her granddaughter. Eight days after the assault, Carroll was arrested for the rape, and he pleaded guilty. According to Price, she tried to share this development with Simons, but the deputy was too busy gathering information on Williams, who was arrested the following month for burglary. (Simons would later disagree and say that it was Price who fingered Williams as a suspect after his arrest.) A mold was promptly made of Williams’s teeth too. This time it was sent to Homer Campbell, the expert in Spence’s trial, along with Washington’s mold and White’s autopsy photos. When Campbell reported his results, his conclusion was different from Hale’s—it was Williams, he said, not Washington, who had bitten White. Nevertheless, Simons believed he had found his men.

Price didn’t agree with him, and neither did several of her fellow WPD officers, so in July, when Feazell held a press conference to announce the indictments, the cops kept their distance. By now the tension between the WPD and the DA’s office had grown to an all-time high. Not long after WFAA’s investigative series on alleged corruption in Feazell’s office had aired the previous year, Feazell had filed a libel suit against the TV station; its parent company, Belo; and one of its reporters. Feazell also included Chief Scott, who had publicly accused him of refusing to prosecute valid criminal cases. The acrimony was about to get even worse. In September 1986 Feazell was arrested on federal racketeering and bribery charges; once again, the DA claimed it was a retaliatory move by local and federal forces for the embarrassment he’d brought to the Texas Rangers in the Henry Lee Lucas case. “I think you all know what’s going on,” the DA told news cameras as he was taken into the federal courthouse in Austin. (He was acquitted of all charges in June 1987, and four years later his libel suit concluded with a jury’s awarding him $58 million, the biggest libel verdict in U.S. history.)

Meanwhile, Price refused to close the White case; though she now had other investigations to work on, she was convinced that Williams and Washington were innocent and spent her spare time interviewing their lawyers and sources on the street. The following summer, in August 1987, Williams went on trial. The case was a slam dunk for prosecutors, who presented the same type of evidence in White’s murder—informant testimony and bite-mark evidence—that had been used against her son just a few years earlier. Eight informants, two of whom had been in jail with Williams, took the stand. Campbell identified four bite marks on White’s body and testified that “the dentition of Mr. Williams [was] consistent with the injury” on her hip.

Though Price had been the police department’s investigating officer, she wasn’t called as a state witness. Instead she, along with three other WPD cops, testified for the defense to say how untrustworthy the informants were. When Williams was nevertheless found guilty and given a life sentence, Price was so peeved that she stepped up her informal investigation. She interviewed Washington and Williams again. She talked to inmates, some of whom claimed that Simons’ sources were liars. Others told her about special treatment that informants got from Simons, who gave them cigarettes, food, and time alone with their wives and girlfriends. (Simons has always denied giving inmates conjugal visits.)

In November Chief Scott decided to make Price’s investigation official. He gave her a partner, Officer Frank Turk, and took them off all other cases so they could look directly into the DA’s and Simons’s handling of the White case. “It’s the only time I’ve ever seen the police investigate a DA,” said Walter Reaves, who, after working as Spence’s lawyer, had gone on to represent Williams. Price and Turk made quick headway. On November 17 they spoke with Otis Douglas, an informant who had testified against Williams. Though he didn’t exactly recant, Douglas told them, “I feel Joe Williams and Calvin Washington are being railroaded.” They then spoke to WPD officer Mike Nicoletti, who gave a statement saying that on October 31 an inmate named Arthur Brandon had told him about a deal he’d made: if he testified against Washington, Simons would drop a pending murder charge. (The charge was indeed dropped, but Simons has said repeatedly that only the DA had the power to drop charges.)

On November 19 a furious Feazell dragged Price and Scott before a grand jury, cross-examined the detective, and demanded that she turn over her files on the White case. Price obliged, agreeing to halt the investigation until after Washington went to trial. But at the end of the hearing, she walked up to the DA and gave him a message. “When I’m done with the White case,” she told him, “I’m going to look into the lake murders.” (Feazell declined to be interviewed for this story, although he did communicate his view that Price’s account of these events was untrustworthy. “Jan Price was arresting our witnesses on the Juanita White case and holding them in the city jail, incommunicado, without access to a magistrate or attorney, trying to pressure them to change their stories,” he wrote in an email.)

Washington’s trial took place that December; he was found guilty and given life. After the trial, Feazell went on the offensive against Price, announcing that he was considering launching a probe for “witness tampering, retaliation, and subornation of perjury” by her and the WPD. Price and Turk returned to their investigation in earnest, tracking down all the informants who had testified against Washington and Williams. Some wouldn’t talk, but three of them recanted their testimony, saying they’d agreed to speak on the record for food, cigarettes, and conjugal visits.

One of these was a woman named Angela Miles, who had been serving time for burglary. At Williams’s trial, she had testified that she saw Williams and Washington in a club parking lot, sitting near White’s car. Now she told Price in detail how Simons had visited her after hearing that she had dated Washington; though she’d told him she had no information to offer, he kept returning, even bringing crime-scene photos. Right before the trial, Simons had written out a statement for her to sign; in it he offered various incriminating facts she knew nothing about. “I don’t know if Calvin Washington or Joe Sidney Williams Jr. killed Mrs. White,” Miles told Price. “I do know that just about every one of the witnesses who said that Calvin or Joe murdered Mrs. White would say anything to benefit themselves.” (In a deposition Simons gave in 1989, he said, “I only talked to Angela Miles one time, and she said that she couldn’t write a statement out, and as she quoted it to me, I wrote it out.” He insisted that he let her examine it. “She didn’t make any changes, she didn’t say anything was wrong with it, and she signed it.”)

The more people Price talked to, the more she doubted the case against Washington and Williams—and wondered about the case against Spence, Deeb, and the Melendez brothers in the lake murders. But the world that she and Turk were investigating was so shadowy that they never got anywhere on the Lake Waco case. Informants they interviewed offered myriad allegations about Feazell and Simons, and the two cops found themselves having to consider the sources. “These people’s whole lives were based on lying,” Price told me.

Price and Turk’s investigation went through May 1988, when she took their findings to the FBI and the U.S. attorney in Waco. Feazell’s antagonism, the open hostility between the DA’s office and the WPD, and the seedy informant underworld she’d spent months in had begun to make her feel paranoid. (“There were times I thought I was going to be ambushed at my house,” she told me.) Now she hoped she could help free Washington and Williams—and cast some light on the DA and his investigator.

But the case went nowhere. “After Feazell was acquitted in the federal case, the feds didn’t want anything more to do with him,” Price remembered. She was devastated. “I was brought up to do things the right way,” she told me. “If something’s not right, you do something about it. To see all this unfolding before my eyes and know I couldn’t stop it was terrible.”

Her ordeal over, Price began keeping tabs on the men who had been sent to death row as a result of Simons’s work, Spence and Deeb. She found herself rooting for two convicted killers. “I was hoping their verdicts would get overturned and they would be tried again so all the details about the investigation would come out.”

In June 1991 she got her wish with Deeb, when the Court of Criminal Appeals overturned his murder conviction. After his direct appeal had been denied, the former shop-keeper, who never wavered in his protestations of innocence, had resolved to free himself: sitting on the floor of his cell at the Ellis Unit, he’d studied law books and typed out cases, trying to learn the rhythms of legal writing. He eventually hammered out a 114-page writ of habeas corpus, a last appeal available to death row inmates in which evidence can be introduced to allege that their trial was unfair. The writ was full of typos but also cogent arguments; Deeb was granted a new trial when the court ruled that the jailhouse informant’s testimony that had been used against him was hearsay.

Spence wasn’t so lucky. The inmate had taken his mother’s death hard; his ex-wife, June Ewing, whom he had married and divorced years before, reported after a visit that he’d stood in the prison yard and screamed at the sky in anguish, “Are you real? Is my mother with you?” Sixteen months after White was murdered, Hunt and Fuller filed Spence’s direct appeal with the CCA. It was denied.

Spence’s execution date was set for October 17, 1991.

III. The Lawyer

In 1991 Texas was carrying out more executions than any other state. After the U.S. Supreme Court reinstituted the death penalty, in 1976, the first Texas execution took place in 1982; by the end of that decade, the state was responsible for 33 of the country’s 116 executions. There were many reasons for this: Texas’s law-and-order tradition, its system of electing tough-on-crime judges, its practice of appointing low-paid, inexperienced defense lawyers. Perhaps more significant, however, was the fact that Texas, unlike many states, had no law requiring that a death row inmate be granted legal representation for his writ of habeas corpus. In fact, it was standard practice for judges to set death dates before inmates had even filed these appeals.

Texas’s execution tally attracted the interest of anti–death penalty activists everywhere, and in 1988 a federally funded nonprofit known as the Texas Resource Center opened its doors in Austin to offer pro bono help to death row inmates, either by connecting them with law firms who could help with their habeas appeals or by representing them in-house. The TRC lawyers faced an enormous task: to persuade the courts that their clients, whom they knew in most cases to be guilty, had received an unfair trial or death sentence and thus deserved a new trial or at least a life sentence. To uncover any facts that might help save their clients—that prosecutors had concealed evidence, for example, or that an inmate had suffered an abusive childhood or was mentally disabled—the attorneys had to reinvestigate every case, searching through files and trial transcripts, visiting with inmates, and traveling far and wide to find old and new witnesses. The lawyers worked nonstop, often juggling several cases at once in a race against the clock, filing appeals and motions up until the very hour of a scheduled execution.

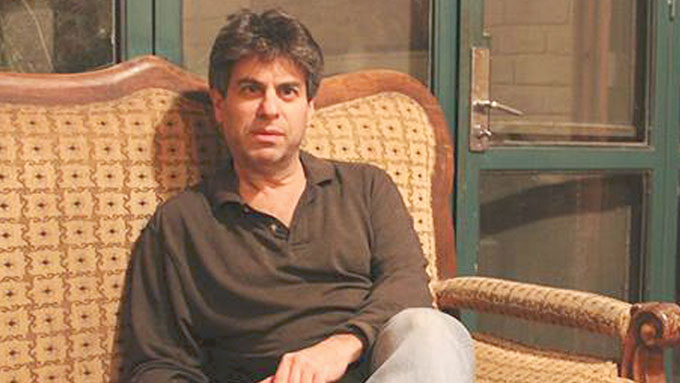

It was grueling, often heartbreaking work, and it tended to attract young, idealistic lawyers, like two attorneys in their late twenties named Rob Owen and Raoul Schonemann. Owen, a Harvard law graduate from Georgia, moved to Texas to work for the nonprofit in 1989; he encouraged Schonemann, an NYU law grad who’d grown up in Ohio and Indiana, to join him a couple of years later. The two had become friends after working one summer in Atlanta on death penalty cases with the American Civil Liberties Union, and they had developed a passion for representing the doomed. When Schonemann arrived for work, in the summer of 1991, he was immediately enthralled by the TRC’s pace. Six or seven full-time lawyers handled five to ten appeals at any given time, for convicts who had sometimes just weeks, or days, to live. “It was one crisis after another,” Schonemann told me. “Like a legal MASH unit.”

David Spence’s case came before the TRC that same summer. The nonprofit’s executive director scrambled to find a firm to represent him, but no one wanted to defend a man who’d twice been convicted of butchering three teenagers. Finally, on Labor Day, with 45 days until his execution, Owen and Schonemann were assigned the case. The two friends quickly got to work, furiously reading through thousands of pages of transcripts from Spence’s two trials and numerous files from the McLennan County DA’s office. The more they understood of the case, the more troubling they found it: the types of evidence used against their client—jailhouse testimony and bite marks—were well-known in legal circles to be unreliable. Other evidence, meanwhile, had never been turned over to defense attorneys, including dozens of police reports that seemed to contradict the murder-for-hire theory. Some reports noted that several people had seen Tab Harper, one of the police’s early suspects, at Koehne Park the night of the murders; witnesses also said he had bragged about killing three people. Other reports contained statements from people who claimed that the victims were heavy drug users; one witness said a friend of a friend had gone to the park that night to collect a $3,000 drug debt from Kenneth.

Then there was the report detailing a bizarre polygraph test taken by Kenneth’s father, Richard Franks. Franks had originally told a newspaper reporter that when his son didn’t return home, he became anxious that Kenneth might be in trouble and went out looking for him at four-thirty in the morning. But later he told the police that he was out driving around the parks at about eight in the evening; this inconsistency, among other details, had prompted Detective Ramon Salinas and Lieutenant Marvin Horton to briefly consider Franks a suspect. The polygraph, given twelve days after the murders, was ultimately inconclusive—yet decidedly strange. According to the report, Franks had become extremely upset toward the end of the test. “Oh, God, I was with them every minute all night when they were killed,” he sobbed. “I don’t have any guilt feelings about causing their deaths.”

“It was all mind-blowing,” Schonemann told me. He and Owen found plenty of evidence implicating others, yet little that pointed to their own client. In fact, not one of the seventeen people interviewed by police who had been at Koehne Park that night mentioned Spence or the Melendez brothers—or anyone who looked like them. It began to dawn on both lawyers that the Spence case was going to be different from any they had handled before.

The two lawyers hit the road, driving all over Central Texas to interview as many original witnesses and jurors as they could find. They also tried to track down all the jailhouse informants. But they were running out of time: Spence had been convicted of murder twice, which meant the lawyers had to file a habeas writ in two trial courts, and it had already taken a month just to read all the documents. On October 16, fourteen hours before Spence was scheduled to die, Owen and Schonemann filed a 164-page writ in each court, in which they stated that in only six weeks of investigating they’d discovered “strong indications of astonishing state misconduct” in the case against Spence for the Lake Waco murders. The prosecutors, Owen and Schonemann wrote, had “engaged in a campaign of deception that was breathtaking in its scope,” including withholding evidence that was exculpatory. The two asked for a stay of execution.

The trial judges postponed Spence’s execution to give the state time to respond, rescheduling the date for December 19. McLennan County DA John Segrest, who had succeeded Vic Feazell, filed a blistering answer. “These are serious allegations against public officials sworn to seek justice,” read the response. There had been no suppression of exculpatory evidence, the brief stated, and the police reports would not have made a difference in Spence’s verdicts. (As for Franks’s polygraph, “without context, it is just as likely that Richard Franks’ statement was that he was with them ‘in spirit.’ ”)

Spence’s prosecutors, in fact, had long maintained that they had turned over everything to the defense that they were required to. At a pretrial hearing in 1984, Spence’s lawyers Russ Hunt and Hayes Fuller had requested that all evidence in the state’s files, even documents the prosecution did not consider exculpatory, be turned over to Judge George Allen for an in-camera inspection in his chambers. The judge had agreed, and Feazell and Ned Butler, the assistant DA, had complied. Allen never disclosed anything from the file to the defense. (Years later, Feazell would tell the Waco Tribune-Herald that the accusation that he had not disclosed exculpatory evidence was “a total lie.”)

But Owen and Schonemann had bought themselves two more months, so they went out on the road again. They knew they had to attack the jailhouse testimony; if Robert Snelson had lied, they figured, other inmates probably had too. Owen tracked down one informant, Jesse Ivy, who had testified that Spence had admitted to killing the teenagers; now Ivy told Owen that Spence had said nothing of the sort. Simons and Butler had shown him photos and given him details, he explained. “The [murders] made me very angry,” Ivy wrote in an affidavit, so he’d talked about them with other inmates. “You could say that Truman Simons and Ned Butler put the facts of the case in my mouth, and I put them into the mouths of the other guys in the jail.”

There was also former inmate Kevin Mikel, who explained how he’d learned details of the murders. “Many times Simons fed me specific pieces of factual information about the crime,” he said in his affidavit, “and then later asked me to relate the information back to him for one of ‘my’ statements.” Simons showed him crime-scene photos and had been the one who told him about the bra tied around Raylene’s ankle. The lawyers found two other jailhouse inmates who had not testified but nevertheless claimed that Simons had fed them information also, offering them leniency and favorable treatment if they turned the words into testimony.

The original case seemed to be unraveling before the lawyers’ eyes. Their suspicions about the jailhouse testimony were further confirmed when they met with Jan Price. “I thought it would be awkward,” Schonemann remembered. “I assumed she wouldn’t be willing to speak with us, but she was candid and forthcoming.” Sitting at a Denny’s in Waco, the three discussed Simons’s work with informants, and Price gave an affidavit about the Juanita White case. “Simons’ ‘investigation’ included numerous promises to jailhouse inmates and the outright fabrication of evidence against the unlucky ‘suspects,’ ” she alleged.

The lawyers also found persuasive reasons to doubt the bite-mark evidence. They met with Lieutenant Horton, who stated in an affidavit that the medical examiner had initially told him that marks on Jill’s breast were “definitely not” bites; it was only after she reexamined the photos and talked with Butler that she changed her opinion. In addition, Owen hired a former president of the American Board of Forensic Odontology, Thomas Krauss, to review Homer Campbell’s conclusions; Krauss pronounced Campbell’s methodology “well outside the mainstream.” The lawyers then found that in August 1984, just two months after Campbell had testified against Spence, he made a mistake that called his expertise into question: he positively identified the remains of a woman alongside a highway in Arizona as those of a missing Florida teenager by comparing the dead woman’s teeth with an enhanced photo of the teenager’s teeth. “They matched exactly,” Campbell told a reporter. Two years later, the teenager turned up alive.

On November 27 Owen and Schonemann filed a supplement to their habeas writs with the Court of Criminal Appeals. The court was not impressed: one week before Spence’s execution date, the judges denied his appeal, sending Owen and Schonemann into another scramble. Their only option now was to go to the federal courts. On December 18, the day before Spence was to die, the lawyers filed for a stay of execution as well as a federal habeas corpus petition, citing 25 grounds for reversal. To their relief, the federal district court granted both. The fight for Spence’s life was back on.

Spence, of course, was not the only client Owen and Schonemann were responsible for; as they worked on his behalf, they were also managing the appeals of several other death row inmates. But Schonemann felt strongly about Spence, and the lawyer made frequent visits to the Ellis Unit to interview the convict. “He had had such an obviously unfair trial,” he told me. “The constitutional violations were egregious.”

The two men could not have been more different. As the mild-mannered Schonemann knew, Spence had a rough history—his ex-girlfriend Christine Juhl had told the police that he beat her, and testimony at the close of his first trial had included allegations of violent rape. But the inmate also had a soft side, composing poetry and writing heartfelt letters to Price, Gilbert Melendez, and Schone-mann himself. He sent gifts to Russ Hunt, including an elaborate stagecoach made out of popsicle sticks and a clock made of matchsticks.

“I was very fond of David,” Schonemann told me. “He was a likable guy, intellectually curious, gregarious. He liked reading about everything and loved talking about religion.” Other TRC lawyers who helped Owen and Schonemann with the case, such as Ken Driggs, agreed—Spence may have been a criminal, but he didn’t seem like a killer. “He’d had a real crappy childhood,” Driggs remembered, “and probably had a lot of anger, but I never read him as a dangerous guy, unlike some others we worked with.” There was no reliable forensic evidence that Spence had killed the teenagers—and to all his lawyers, he had consistently maintained his innocence. Yet there was one nagging question: How to explain the many people who’d heard him say he was the murderer? They couldn’t all be lying.

A possible answer came from Spence’s ex-wife, June, who, besides Schonemann, was one of the inmate’s most consistent visitors. On her first visit, she’d demanded to know the truth, and then she’d kept asking. “I’d say, ‘David, if you did this, you deserve to die,’ ” she told me when we talked last May. “He’d say, ‘June, I didn’t do this.’ ” Once a year, she would bring the couple’s two sons, Joel and Jason, for a four-hour, no-contact visit. He had never been violent with her or them, she recalled. “We used to fight. I’d knock the shit out of him, and he’d say, ‘You done?’ He never bullied me or bit me. He wasn’t perfect. He wasn’t very intelligent. But he was kindhearted to those he loved. I left him because he was drinking and smoking too much weed.”