This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

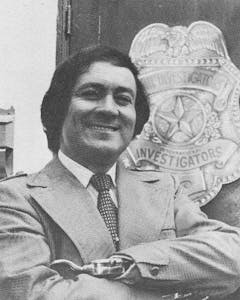

Jay J. Armes was running short on patience and long on doubt. He was slipping out of character. It was possible he had made a mistake. The self-proclaimed world’s greatest private detective, an internationally famous investigator who liked to brag that he’s never accepted a case he didn’t solve, fast on his way to becoming a legend, was stumbling through a television interview with a crew of Canadians who never seemed to be in the right place at the right time, or to have the right equipment, or to ask the right questions.

Jay Armes calculated that his time was worth $10,000 a day, which meant that the three-man crew from Toronto had gone through $15,000, on the house. Pretty much ignoring his suggestions, the Canadians had concentrated on what Armes called “Mickey Mouse shots” of the “Nairobi Village” menagerie in the backyard of his high-security El Paso home, and on his bulletproof, super-customed, chauffeur-driven 1975 Cadillac limousine.

Worse still, the Canadians were not from the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, as Armes has led himself to believe, but from CTV, a smaller independent network. He had badly overestimated the value of this publicity. The seeds of discord had been scattered unexpectedly the previous day, at a corner table of El Paso’s Miguel Steak and Spirits where Jay Armes sat with his back to the wall regaling the Canadians and two American magazine writers with tales of his escapades, or “capers,” as he called them.

He talked of the long helicopter search and dramatic rescue of Marlon Brando’s son Christian from a remote Mexican seaside cave where the lad was being held by eight dangerous hippies; of the time he piloted his glider into Cuba and recovered $2 million of his client’s “assets”; of the famous Mexican prison break, another helicopter caper which, he said, inspired the Charles Bronson movie Breakout; of the “Onion King Caper” in which a beautiful model shot her octogenarian husband, then turned a shotgun on herself because Armes wouldn’t spend the night with her—all incredible adventures of a super-sleuth, adventures made more incredible by the fact that both of Jay Armes’ hands had been blown off in a childhood dynamite accident.

He raised one of his gleaming steel hooks, signaling the waitress, still watching the faces around the table. Too much, they said in admiration: how did he do it? “I read the book,” Armes replied enigmatically, “and I saw the play.” That was one of his best lines.

At another table strategically positioned between his boss and the front door sat Jay Armes’ chauffeur-bodyguard, Fred Marshall, a large, taciturn man who used to sell potato chips. You could not detect the .38 under the coat of his navy-blue uniform. When they traveled in the limousine, which was a sort of floating office, laboratory, and fortress, Fred kept what appeared to be a submachine gun near his right leg. Armes claimed there had been thirteen or fourteen—the number varied from interview to interview—attempts on his life, a figure that did not include the six or seven times he had been wounded in the line of duty. He lifted his pants leg and exhibited what appeared to be a small-caliber bullet wound through his calf.

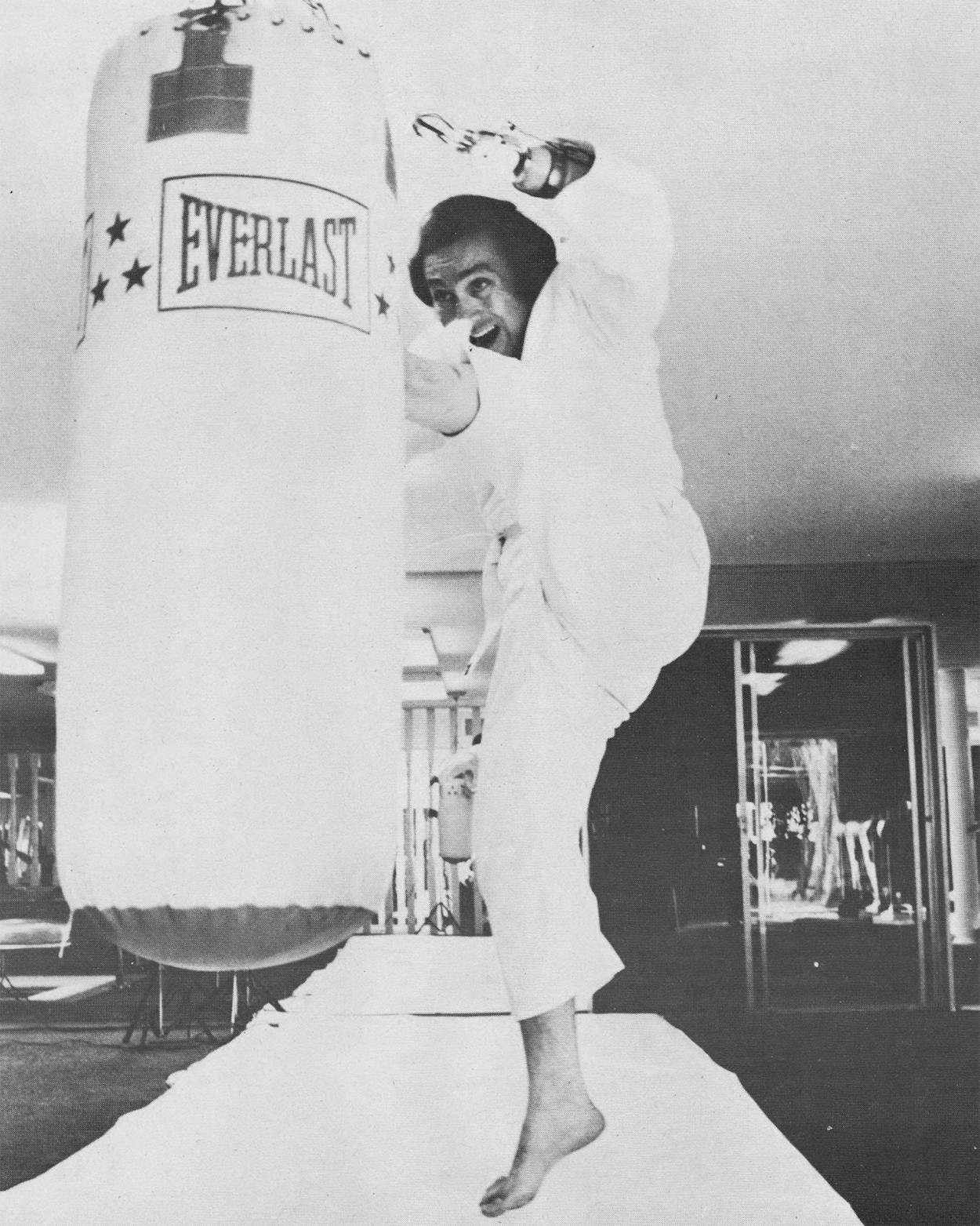

Concealed on his left hip, under his immaculate, custom-tailored suit with epaulets and belted back, was a .38 Special; implanted in the base of the hook on his right arm was a .22 magnum. What’s more, he told CTV producer Heinz Avigdor, he held a third-degree black belt in karate—and that was the point of the ensuing argument.

“I want to show you what a black belt does, besides hold your gi [karate regalia] up,” he smiled at the producer. “Look, I’ve been in a lot of films, I know what I’m talking about. Do it my way, I’ll show you what it’s all about.”

Armes had called ahead and cleared the plan with the Miguel manager. It would be a scene right out of The Investigator, a proposed television series which, according to Armes, CBS would begin filming right here in El Paso, right here at the Miguel, in fact, on January 20. CBS planned a pilot film and 23 episodes, all of the stories adapted from Armes’ personal files. Jay J. Armes, of course, would play the title role of Jay J. Armes.

This was the scenario Armes outlined for the CTV producer:

As soon as the Canadians had positioned their lights and camera, a telephone would ring. Armes would be paged. Fred would presumably go on eating his steak and chili. As Armes approached the lobby he could be confronted by a large Oriental who would grab him by the collar and say, “You’ve been pushing around the wrong people, Armes.” Jay would then project his thin smile, inform the Oriental that he was a man of peace, then flip the startled giant over his shoulder with a lightning-quick maneuver of his hooks. A second man would charge him with a pepper mill. Armes would deflect the blow with one of his steel hands, jump into the air, and paralyze the second assailant with a judo chop.

“Uh, Jay,” producer Heinz Avigdor said feebly, “I think that is a bit dramatic for the purposes of our show. We’re doing a documentary. I think perhaps a workout in your private exercise room, wearing your karate outfit, then some footage in your shooting range downstairs, and maybe a shot in your library. Something from real life, you see.”

Jay Armes saw, all right: he saw that the producer was a fool.

“I’m offering you something from real life,” he said, that edge of impatience returning to his voice.

“But, Jay, it’s so . . . so staged,” Avigdor argued. “W-5 isn’t that sort of show.”

“It’s real,” Armes snapped, and the pitch of his voice was much higher. “What you’re talking about isn’t real. There’s nothing real about working out in a gym, with a body bag, wearing a stupid gi. This way, I’ll be in a suit and tie in a public place doing my work, exactly like real life.”

Avigdor protested that his crew didn’t have the manpower or equipment for the scene Jay was suggesting. Jay sighed, adjusted his hooks to the fork and knife. He changed the subject abruptly: he began telling the two magazine writers about his secret code, and about his dissolvable stationary that you could stir in a glass of water and drink.

But the affront hung in his mind, and he began to speak of the amateurish approach of the Canadians, about how when 60 Minutes comes to El Paso in a few weeks to do the Jay Armes story the CTV crew would be eating tin cans. He estimated that the 60 Minutes segment would be worth $2 million in publicity, and would probably get him elected sheriff of El Paso County, a post he covets not for personal gain but in the interest of justice. “When I decided to run for sheriff,” he said, “I telephoned my producer at CBS and he said, great, what can I do to help?” The producer’s name was Leonard Freeman, and what he agreed to do, Armes continued, was send the 60 Minutes people to El Paso. The show would appear in January, a week before the election.

“Look,” Armes told Avigdor. “I’ve tried to be patient with you guys. I wore the same suit two days in a row—I won’t even look at this suit for at least a year now. I invited you into my home. I took time out from my work. I showed you around. I called my producer at CBS a little while ago, and, frankly, he told me to blow you off.”

Armes was smiling, but it wasn’t his dark, boyish face and licorice-drop eyes that captured attention, it was those powerful, gleaming steel hooks. Each hook could apply 38 pounds of pressure per square inch, three times that of a normal hand. They were sensitive and deadly, these hooks, and he used them the way a surgeon uses his hands, picking rather than hacking, demonstrating, extracting, mesmerizing, proving precisely what it means for a man to turn a liability into an asset. Somewhere in those gestures was the message: I’ll bet you couldn’t do this. And yet what you saw was not an amazingly skilled man who could shoot and play tennis and paint and do pushups, what you saw was the dark bore of a .22 magnum inches from your forehead. It was rimmed with black powder and projected an even more deadly threat than the threat of the hooks—the threat of subconscious impulse, unchecked by distance or time—for the trigger mechanism of this weapon was connected by tiny wires to Armes’ right biceps. The operation cost $50,000, Armes added, and was performed by a New York surgeon named Bechtol. Don’t worry, he said, it has a fail-safe: it can’t go off by accident.

“It can only be fired by my brain,” Armes had told us. “It’s like . . . let me put this right . . . like opening your mouth. Your brain can tell you to open your mouth, but it doesn’t just fly open by itself.”

That was the same day that Armes asked Avigdor and his two technicians why it was that “Canadians condone concubines.” Armes said he had known many cases, especially among French Canadians, in which prominent men “kept concubines [sic] of fifteen and even twenty women.”

I don’t know if Armes noticed, but Heinz Avigdor’s mouth dropped wide enough to accommodate a jack rabbit.

The first thing you see when you enter Jay Armes’ office at 1717 Montana in El Paso is a mural on the wall at the end of the hallway. The mural depicts a man in a trench coat and hat, cradling the world in one arm. Painted on the face of the globe are all the cities where Jay Armes operates branch offices. On closer inspection, the man in the trench coat turns out to be Jay Armes. It is a self-portrait.

There are other Jay Armes paintings throughout the office, and throughout his home, mostly of long, graceful tigers springing at some prey off canvas.

The office has a jungle motif. The rooms are dimly lit in eerie reds and greens. “Psychological lighting,” Armes says. Armes says he employs more than 2000 full-time agents—600 right here in El Paso—but the employees visible are a secretary who sits in the front office, and the faithful bodyguard Fred, who lurks nearby.

Armes escorts the visitors to his crime lab. On a long table under the weird green light, laid out like oranges in an autopsy, is a curious assortment of detective gimmicks—the latest touch-tone portable telephone, its range worldwide; a de-bugger that Armes values at $10,000; a Dick Tracy–like wristwatch recorder; a tranquilizer gun that shoots sleeping gas; many small bugging devices; and two microscopes. Armes says he can do a complete laboratory breakdown here. In addition to his mastery of chemistry, Armes says he has degrees in psychology and criminology from New York University, as well as the ability to speak seven languages, including thirty-three dialects of Chinese.

Photographs on the wall and in the fat scrapbook show Armes in diving equipment, or playing with his lions and tigers, or firing on his pistol range. There is a photograph of his son, Jay Armes III, riding a pet lion. Jay III used to have a pet elephant, but a neighbor shot it with a crossbow. In a rear room with a coffee pot and a copying machine, Armes points out several bullet holes in the window and door, the marks of that night when an assassin sprayed the building with a .45-caliber grease gun.

Armes leads the visitors to his private office and site at his desk, his back to 71 volumes of Corpus Juris. On the wall are the framed diplomas testifying that Jay J. Armes is a graduate of a number of detective academies, and a member of a number of detective associations. One of the academies is the Central Bureau of Investigation in Hollywood. Curiously, there is no diploma from NYU. But Armes tells a story about how his old mentor, Professor Max Falen, discovered Armes was working his way through NYU as a dishwasher. “He blew his stack,” Jay says. “He said I was shortchanging criminology.” Falen arranged for his prize student to receive a paid student assistantship and moved him into his own home. The years passed, and poor Max Falen began hitting the bottle. NYU finally had to let him go. When Jay learned what fate had befallen his onetime friend and benefactor, he hired the professor and moved him to the Los Angeles bureau of The Investigators.

Although he graduated with honors at age nineteen, Jay Armes soon learned there were few openings for criminologists. That’s when he decided to open his own detective agency.

“I wanted to clean up the image of the profession,” he says. “In TV and the movies, private detectives are usually pictured as crooked ex-cops who keep a filing cabinet of booze and work both sides of the street.” Jay pointed out that he did not smoke or drink (not even coffee), and was “deeply religious.” Ten percent of everything he makes goes to the Immanuel Baptist Church in El Paso. A secretary at the church later confirmed that Armes “attends regularly and gives generously.”

Although Armes is seen regularly at church, at the El Paso Club and Empire Club, at the police station or courthouse, and cruising the streets in his black limo, he remains a mystery man to most citizens of El Paso. Most of what they know about him comes from recent articles in magazines like People, Newsweek, and Atlantic, or from national TV talk shows.

According to Newsweek, Armes “keeps a loaded submachine gun in his $37,000 Rolls Royce as protection against the next—and fourteenth—attempt on his life. He lives behind an electrified fence in a million-dollar mansion with a shooting range, a $90,000 gymnasium and a private menagerie, complete with leopards that prowl the grounds unchained at night. He is an expert on bugging, a skilled pilot, a deadly marksman and karate fighter and, perhaps, the best private eye in the country.”

The article in People was similar, except for a couple of discrepancies. According to People, Armes earned his degrees in criminology and psychology from UCLA, not NYU. And they referred to him as “recently divorced.”

“My wife went through the ceiling when she read that,” Armes said. His wife Linda Chew is the daughter of a respected Chinese grocer. She is a handsome, soft-spoken woman who seems to accept her husband’s chosen role with traditional stoicism. “When I leave home in the morning,” Armes says, “she never knows if she will see me again.”

Armes doesn’t especially enjoy discussing his childhood in Ysleta. The Lower Valley, as it is called, was a mostly lower-class, predominantly Mexican-American area of small farms and run-down businesses and ancient Indian teachings. It’s now part of El Paso, but it was another town when Armes grew up. As Armes tells it, he was born August 12, 1939, to Jay Sr. and Beatrice Armes. His parents were Italian and French. His father ran a grocery.

“I was a tough kid, like the sidewalk types of Chicago,” he recalls. “I had to fight for what I thought was right. I was always at the head of the class, captain of the football team, a boxer, a basketball player, a star in track. Even after I lost my hands I still played all sports.”

Armes remembers that he was about eleven when the accident happened. An older boy of about eighteen found some railroad torpedoes beside the track and brought them to Jay’s house. The older boy stood back and told Jay to beat the torpedoes together. He did, and they blew his hands off just above the wrists. The accident hardly seemed to slow him down. He recalled holding down four jobs, and running a loan-shark operation across the street from the school. “I’d loan a quarter and get back fifty cents,” he said, and the memory seemed to please him. “If someone was slow in paying, I’d kick ass.”

What he says happened next is straight out of the Lana Turner saga. Jay was drinking a milk shake in the Hilton Plaza drugstore when a Hollywood casting director named Frank Windsor strolled over and said: “Hey, kid, you’re pretty good with those mitts.” The casting director offered Jay a part in a movie called Am I Handicapped?, starring Dana Andrews.

Jay was barely fifteen—he recalled that he had just started taking flying lessons—when he quit school and moved to Hollywood. The next few years are vague in his recollection, but they apparently weren’t dull. He graduated from Hollywood High, landed roles in thirteen feature-length movies, studied one year (1959) at UCLA, moved to New York, did three years (or, as he sometimes remembers, six) at NYU, and returned to El Paso, a triumphant nineteen-year-old determined to change the image of his new profession. Somewhere in there he also graduated from the Central Bureau of Investigation in Hollywood.

Why El Paso, the visitor wonders? With that background, why go home again?

Jay says, “I am deeply religious. It says in the Bible that you will not prosper in your hometown. How could a carpenter’s son become king of the Jews? Jesus had to go to Nazareth to be recognized.”

Was he trying to outdo Jesus?

“I was trying to see if this was a fact,” he says. “And it is. I am recognized now all over the world more than I am in my hometown.”

While the crew from CTV is setting up outside on Montana Street, I take another look around. There is something too deliberate about the way those crime-fighting gimmicks are laid out on that table under the green light in the lab, like toys under a Christmas tree. The holes from the .45 caliber grease-gun would be more impressive if they had smashed the glass or shattered the thin layer of wood instead of leaving clean, neat punctures. I glance through the Jay J. Armes Training Academy correspondence course, which can be had for $300. Sample question: “Eighty percent of people do not see accurately because:

(a) they have a stigmatism

(b) there is too much smog in the air

(c) because they do not pay attention

(d) because they usually just watch the ground.”

I wonder if the Central Bureau of Investigation was like this. Then something else catches my eye—the mural at the end of the hallway, the self-portrait. I didn’t notice before, but Jay Armes has given himself blue eyes. And that’s not a hook holding the world, it’s a hand.

Fred, the ex-potato chip salesman, stands at attention, holding the rear door of the limo open for Jay Armes and his guests. There are a few rules you learn in Jay Armes’ company: you do not smoke, you do not swear, and you do not open your own limousine door. A New York book editor who was in El Paso a few weeks earlier recalled the door ritual as his most vivid impression. Jay Armes always got out first, explaining that “I’m armed. I can protect my friends.”

As the black limousine pulls silently into the traffic and winds past the refinery adjacent to IH 10, Armes reaches out with his hooks and activates the video tape camera buried in the trunk lid of the car. On the black-and-white screen we can see the CTV station wagon trailing us. Sometimes, Armes tells us, he uses the video tape gear to follow other people. “While they’re looking in their rearview mirror,” he says, “I’m right in front of them watching their every move.”

The limo is also equipped with a police siren, a yelper, and a public-address system, each of which he demonstrates. There is a front-seat telephone and a back-seat telephone with a different number, revolving license plates, and Jay Armes’ crest on each door. You might suppose all these trappings would make it difficult to remain inconspicuous, but Jay has his methods. “I read the book,” he says, “and I saw the play.” Sometimes he uses a panel truck with Acme Plumbing on the side. Or the bronze Corvette with the Interpol sticker on the back. He even has a stand-in. Somewhere in El Paso there is another Jay J. Armes.

The limousine pulls off 1H 10 and follows a narrow blacktop along rows of cheap houses, hotdog stands, and weed fields. This is not exactly your silk-stocking neighborhood.

Armes has been talking about his $50,000 fee for cracking a recent jewel robbery at the UN Plaza apartments in New York, and about a potential half-million dollar fee that he turned down on advice of his attorney. Working through his producer, Leonard Freeman, a national magazine that he is not at liberty to identify offered Armes that sum to locate Patty Hearst, which he boasted he could do in three weeks or less. “The FBI called and said, hey Jay, how can you find her in three weeks? I said: ‘cause I know my business.” In return for its money, the magazine wanted Armes to guarantee an exclusive 30,000-word interview with the mysterious heiress, and that’s when Armes pulled out. “Even admitting to you now that I had her located,” he said, “could subject me to criminal prosecution. But I’ll tell you this much, that’s a damn lie about her being in school in Sacramento. I’m writing a book for Macmillan, maybe I’ll tell the true story. The FBI actually put a tail on my book publisher, thought maybe he’d lead them to Patty Hearst. I’ll say one more thing. I’ll bet you $10,000 that Patty will never be convicted.”

Outside the eighteen-foot electrified fence that runs along the 8100 block of North Loop, Fred activates a small electronic box above his head and the gates swing open. He parks the car in front of Jay J. Armes’ curious little mansion with its tall columns and flanking white stone lions.

A Rolls, Corvette, and several other cars are parked in the driveway between the house and the tennis court. Gypsy, Armes’ pet chimpanzee, screeches from her cage until Armes walks over and swaps her a piece of sugarless gum for a kiss. A pack of dogs hangs back, menacingly.

While the crew from CTV is hauling its equipment upstairs to the library, Armes conducts a tour of the Nairobi Village in the backyard. Armes stiffens when visitors refer to this as a “zoo,” and with good reason: this place is right out of a Tarzan movie, except that most of the animals are caged. There are thatched huts, exotic plants, narrow trails through high walls of bamboo, and a lighted artificial waterfall beside a man-made lake. Though the lake is not much larger than a hockey rink, there is what appears to be a high-powered speedboat anchored against the far bank. And on the bank nearest to the house, inside a corral of zebras and small horses, sits a twin-blade helicopter. This is the chopper, Armes reveals, that he uses most often. He can have it fueled and airborne in less than half an hour. He also says he owns a jet helicopter (it’s presently in Houston), a Riley turbojet, and a Hughes 500.

In the heart of the jungle, a telephone rings. Armes opens a box on the side of a palm tree and talks to someone. Then the tour resumes.

“When I was a kid,” Armes says, “I couldn’t even afford a good cat. I decided that when I got older and could afford it, I’d buy every animal I could find.” So far he has found 22 different species, including a pair of black panthers from India, some miniature Tibetan horses that shrink with each generation, some ostriches, a West Texas puma, and a 400-pound Siberian tiger that roams the grounds at night, discouraging drop-in visitors. Many of his prize animals, he tells the visitors, are currently grazing on his 20,000-acre Three Rivers Ranch in New Mexico.

Armes opens the tiger cage and invites his guests inside. They politely decline. He smiles, having already detected the presence of fear in the tiger’s movements. The tiger seems suddenly irritable. Armes talks to the tiger and strokes its head. The tiger rears back and Armes controls it with a skilled movement of his steel wrists.

Entering Jay Armes’ mansion is yet another trip beyond the fringe: it is something like entering the living room of an eccentric aunt who just returned from the World’s Fair. There is a feeling of incongruity, of massive accumulations of things that don’t fit, passages that lead nowhere, bells that don’t ring.

We wait in what I guess you would call the bar. The décor might be described as Neo-Earth in Upheaval. It was as though alien species had by some unexplained cataclysm been transposed to a common ground. Dark green water trickles from rocks and runs sluggishly along a concrete duct that divides the room. There are concrete palm trees, artificial flowers, and stuffed animals and birds. Two Japanese bridges span the duct, and the walls sag with fishnets, bright bulbs, African masks, and paintings of tigers. There is a piano in one corner, but Jay Armes does not volunteer to demonstrate the skill just now. Although neither Armes nor his wife Linda drink, the bar is well-stocked with Jack Daniels, Chivas Regal, Beefeater, and two varieties of beer on tap.

In an adjacent room, what appears to be a living coconut palm floats in a tub in the indoor swimming pool. Though the pool is small, it takes up most of the room. In one corner of the room, hidden behind a thatched bar, is a washer and dryer and a neat stack of freshly laundered children’s clothes.

The room behind the swimming pool is Jay’s exercise room. Steps lead down to his computerized target range in the basement. After his customary two-and-a-half hours sleep, Jay wakes around 4 a.m., dictates into his recorder, exercises with his karate instructor, practices on his target range, has a sauna and a shower, selects one of the suits with the epaulets from a closet that he estimates contains about 700 suits valued at $500 a pop, has a high-protein breakfast, and calls for Fred to bring the limousine around.

“Almost every day of my life,” he says, “there is some violent or potentially violent incident. I have to stay in tip-top shape.” His single vice is work. “The Lord has given us a brain,” he says. “We only use one-tenth of ten percent of it. The rest is dormant. That’s because we are lazy. I try to use as much of my brain as I can.” Armes claims that he personally worked on 200 cases last year, and that doesn’t count the thousands of cases in the hands of his more than 2000 agents.

Like the other rooms, there is a disturbing incongruity to the exercise room. It’s too neat, too formal. The equipment is the kind you would find at a reducing salon for middle-aged women. It’s mostly the easy stuff that works for you.

Upstairs above the exercise room is the Armes’ master bedroom. Scarlet O’Hara would have loved it. Flaming red carpet, flaming red fur spread, a lot of mirrors, and the ever-present eye of the security scanner. From the video screen beside his circular bed, Jay Armes can watch any point in or outside the house.

Armes is pacing like a cat: the CTV crew is still not ready in the library. He leads the two magazine writers downstairs again, to his shooting range where he demonstrates both the .38 and .22 magnum.

“Yes,” he says, “I have killed people. I don’t want to talk about it. It’s sad . . . no one has a monopoly on life. But it’s like war. Sometimes you must take a life in the line of duty. I’m guarding some diamonds, say, my job is to protect my client’s property. If someone gets in the way, maybe I’ll have to kill him. But I don’t like to talk about it.”

Then he tells of a caper in which he rescued a fifteen-year-old girl runaway from an apartment somewhere in New Mexico. He kicked open the door and a hippie with a .32 shot him three times. The third bullet struck less than an inch from his heart. There was no time for the .38. Armes raised his right arm and killed the hippie with a single .22 slug square between the eyes. “Remind me to show you a picture of it when we get back to the office,” he says. Bleeding like hell, Armes drove the runaway girl back to her parent’s house in El Paso. Only then did he drive himself to the hospital.

“It’s funny,” he says, “but when I get shot, I seem to get super strength. I know the Lord is looking after me.”

When the TV camera is finally in place, Armes goes up to the library and stands in front of a painting of a tiger which is actually a secret door to the children’s room. On cue from Heinz Avigdor, Jay Armes shows off his gun collection, and tells a little story about each weapon. I had examined all this hardware earlier, so I excused myself and walked down to the bar where I telephoned a friend.

Through the fishnet and the porthole window I could get a closer look at Jay Armes’ helicopter. From appearances, it hadn’t been off the ground in years: its tires were deflated and hub-deep in hard ground, the blades were caked with dirt and grease, and the windows were covered with tape instead of glass. Armes had told us that the chopper had a brand-new engine. I wondered why he hadn’t put glass in the windows.

I walked back upstairs and told Armes that I had to get back to town. I made up a lie about having dinner with my old college roommate.

“Say hello to Joe Shepard,” Armes said with a thin smile.

Is Jay J. Armes for real?” I asked Joe Shepard as we devoured the grub du jour of his favorite Juarez hangout.

“No way in hell,” Joe said. At least that was his hunch. Like almost everyone else in El Paso, Shepsy (as he calls himself) knew Jay J. Armes only by reputation. He was that mystery man in the black limo. You’d see that big sinister Cadillac glide up in front of the police station or the courthouse, Fred would pop out, look around, open the door, and Jay Armes would hustle up the steps, his head low and his hooks locked contemplatively behind his back. They had all read about Armes and seen him on TV talk shows. He lived behind that eighteen-foot electric fence way out on North Loop, in a poor section of town, in that white mansion with the never-land façade, next to the parked helicopter, next to the miniature lake. They had heard that wild animals roamed the estate.

Shepsy had heard, too, about the repeated attempts on Armes’ life and had concluded: “El Paso must have the worst assassins in America. If I wanted to shoot Jay Armes I’d sit across the street from the courthouse for an hour or two.”

Shepsy is a licensed private investigator. He showed me his card. License number A-01123-9. True, he didn’t know Jay J. Armes, but he knew enough to dislike him.

“I don’t want to sound like sour grapes,” Shepsy said, ordering another round of tequila and beer, “but it’s not that difficult to run a magic lantern show in this business. The more sophisticated a client is, the easier it is to take them. They seem to feel an obligation to understand what you’re doing. The wife of Dr. ——- [he named an El Paso surgeon] hired me to shadow him—I could have worked her for 50,000 bucks, that’s how sophisticated she wanted to be. But I didn’t. I checked the doctor—there was nothing to it, so I dropped it.

“A good investigator will find out what a client wants to hear. After that, it’s no problem to write a report. The hell of it is, there are a lot of poor people getting ripped off, too. You have no idea how many poor husbands or wives will take everything out of their savings and hire a private investigator. They feel trapped, they don’t know what’s going on in their lives. . . . I guess they believe it’s like it is on television.”

Shepsy is 43, the same age as Jay J. Armes, although Armes claims to be 36. Shepsy has been frequently married, and his life is constantly in danger from his current wife, Jackie, a high-spirited, free-lance nurse anesthetist who supports his unorthodox lifestyle and sometimes heaps his clothes on the back porch and burns them. Shepsy drives a red VW and has never owned a gun in his life.

“If I carried a gun,” he said, “sooner or later someone would take it away and shoot me. If someone is going to shoot ol’ Shepsy he’s damn sure gonna have to bring his own gun.”

Nothing was just what it seemed. So was everything.

None of Shepsy’s wives, including the pretty incumbent Jackie, could get it through their heads that he was really spending all those lonely nights perched in a tree watching bedroom windows through binoculars.

They had been married about four months when Jackie hired Jay J. Armes to check out Shepsy’s story that he was flying to Albuquerque on business. She paid Armes $300—she’s still got the check to prove it—and he reported back by telephone. The entire substance of his report was that one of his “operatives” followed Shepsy and, sure enough, Shepsy had driven to the airport. He made a couple of “mysterious phone calls,” then boarded the flight for Albuquerque, exactly as he said. Case closed. Fee paid.

“Nobody followed me,” Shepsy said. “Not in a New York minute. I wasn’t anywhere close to the airport that night. I drove to Albuquerque with my clients.”

Shepsy had heard all about those fantastic fees that Jay Armes commanded, but he was skeptical. Nobody in the business charges like that—not half a million, not $100,000, not even $10,000. Shepsy works for $15 an hour, or $150 a day, plus expenses. One of his larger cases popped up just that morning when a distraught father paid him $500 to prove that his daughter was dating a homosexual, which in fact she was. What a price to pay for truth.

But this was a border town; the rules were a little different. Nothing was just what it seemed. So was everything. For $50 you could have someone killed. Any Juarez cab driver could arrange it. Investigators knew the rules of operating in Mexico—speak the language and have the money. They all heard about the 25 grand Jay Armes got for rescuing Marlon Brando’s son. They believed it. They didn’t believe the part about the three-day helicopter search in which Jay Armes survived on water, chewing gum, and guts, but they all knew the trick of grabbing a kid. You hired a couple of federales or gunsels. The problem wasn’t finding the kid, it was getting him out of the country.

I told Joe Shepard what Armes had said as I was leaving. He’d said: “Say hello to Joe Shepard.” I don’t know how he knew I was meeting Joe Shepard.

The next night I had dinner with Joe and Jackie and some of their friends, and the entire conversation was Jay J. Armes. It turned out that Jackie had gone to Ysleta High School with Linda Chew, Armes’ wife. Jackie recalled that Linda was shy and obedient, a hard worker. Jackie’s friend, Guillermina Reyes, hired Armes a few months ago to substantiate her contention that the business manager of Newark Hospital was embezzling funds. Mina had been fired from her receptionist job by the business manager, but the hospital board had agreed to hear her story and she needed some hard evidence.

“This was last August,” Mina told me. “I hadn’t heard of Jay J. Armes at the time—I picked him out of the phone book. I went to his office and told him my problem and he said he would look into it for $1500. That shook me up. Then he said, how about $700? I apologized and said he was way out of my range, so he said, ‘How much have you got?’ ”

Mina finally paid Armes $150, and several weeks later, Armes told her, “I checked it out. This guy is clean.” That was the entire report. A few weeks later Mina and everyone else began hearing just how clean Ramirez was—the Newark business manager was arrested, charged with embezzling funds in the amount of some $21,000, and placed under $500,000 bond. Whatever the truth, Jay J. Armes hadn’t exactly resembled the world’s, or even El Paso’s, greatest detective.

Brunson Moore, a lawyer and former El Paso JP, recalled a time when the Armes had performed spectacularly in a domestic case involving a husband who thought his young wife was playing around. She was playing around alright—Armes gained entry into her apartment and produced some amazing movies. The wife’s co-star turned out to be the pastor of one of El Paso’s larger churches. The films were not admissible evidence, of course, but the pastor soon moved out of town.

Clarence Moyers, an attorney, had a Jay J. Armes story. This was a couple of years ago, when Moyers was getting a divorce. Jay Armes telephoned, very familiar, very friendly, saying, “Clarence, ol’ buddy, I’ve been out of town and a terrible thing happened to you while I was gone.”

“I had never spoken to Jay Armes,” Moyers said, “but suddenly he’s laying it on me how his agents didn’t realize what great buddies we were, so they accepted an assignment from my ex-wife to do an investigation on me. Armes said he had a stack of pictures a foot deep. He said he was sitting there right then looking at one of me in a daisy chain. I asked him what a daisy chain was, and he told me. Well, I hadn’t been in a daisy chain recently, but I was still worried. Then he got to the point: he said my ex-wife had paid his agents $3,000 cash, so if I’d put up another $300 he’d give me the pictures and return my ex-wife’s money.”

Moyers instructed Jay Armes what to do with his pictures and hung up. When he confronted his ex-wife later, she denied ever hiring Armes or one of Armes’ agents.

There was a paradox here. Jay J. Armes’ stories didn’t check, yet the man was absolutely larger than life. He didn’t support his flamboyant lifestyle by misleading poor receptionists or working both sides in domestic cases. This riddle of Jay Armes hung in some dark passageway; tracing it back was like looking in old encyclopedias for new discoveries. The city directory, for example, first took note of Jay. J. Armes in 1957, when he should have been in California. Armes operated the Central Bureau of Investigation, named no doubt for the detective course he took in Hollywood. His office was in the Caples Building, the old seven-story warren of bail bondsmen, quicky finance companies, and ambulance chasers. “The Investigators” first appeared in 1963.

Joe Shepard nudged me with his elbow and motioned to follow him outside. We walked to a remote corner of the parking lot, and stood on a high ledge overlooking the lights of El Paso. Shepsy waited while a small aircraft passed overhead.

Then he said in a low voice, “The reason you’re having trouble tracing Jay Armes is that’s not his real name. He’s really Julian Armas.”

He pronounced it hool-yon are-mas.

Julian Armas was born August 12, 1932. His father was Pedro, not Jay Sr., and his mother was Beatriz. Pedro didn’t own a grocery store as had been claimed, but he worked in one. He was a butcher at the P&N Grocery store in Ysleta. “He worked hard and drank his beer,” recalled Eddy Powell, who used to own the store. Like Professor Max Falen, Pedro had a drinking problem. Pedro and Beatriz Armas and their five children were Mexican-American. Not Italians. Not French. Julian, a friend recalled, didn’t speak English until he started school.

Records in the El Paso County Courthouse show that Julian was nearly fourteen when he jabbed the railroad torpedoes with an ice pick and blew off both of his hands. A negligence suit filed against the Texas & Pacific Railroad on December 6, 1948, claimed 70 per cent disability and asked for $103,000 in damages, based on Julian’s estimated total income for the next forty-six years. The case was dismissed. The way Armes, or Armas, tells it, he was awarded an $80,000 settlement, which he gave to his family. A lawyer connected with the case said Armas collected nothing.

“The boys didn’t find the torpedoes beside the track,” the lawyer said. “They broke into a section house. There was no evidence of negligence on the part of the railroad.”

Margaret Caples Abraham recalled the day of the accident. It happened in the chicken yard behind her house. She was about seven at the time. It was her brother, Dickie Caples, who was with Julian. When Margaret and her family returned from a Saturday afternoon shopping trip, the boys were gone and the chickens were pecking on bits of flesh and small fingers. Dickie wasn’t injured, but the trauma of that day still haunts him. Curiously, the Caples own the Caples Building where Jay. J. Armes first started his detective business.

Van Turner helped Julian get fitted with his hooks. Van and Julian attended the same Catholic Church and were members of Boy Scout Troop 95. They also shared a paper route. Julian operated a motor scooter specially customed with two bolts instead of handle grips, and Van rode on the back.

“I never made any money from the paper route,” Van Turned recalled. “I never knew what Jay did for money. I felt sorry for him.”

Van Turner remembered that the other kids helped Julian with his homework. After two years of high school, Julian split for California. “When he came home seven or eight years later,” Turner said, “he had changed. He was always sort of a bully, but now he was very obnoxious.”

“He came back with a different attitude,” said Rudy Resendez, who also delivered newspapers with Julian Armas. Resendez is now principal of an elementary school in Ysleta. “It was like he had to prove himself. He was a strange person. Nobody could get close to him. He gave the impression that he was better than anyone else.”

Old friends recalled well when he returned from California. Julian, or Jay J. Armes as he now called himself, drove an old, raggedy-topped Cadillac with a live lion in the back and a dummy telephone mounted to the dashboard. He would pull up beside the girls at the drive-in and pretend to be talking to some secret agent in some foreign land.

“For most people, losing both hands would be the end of the show; for him, it was the beginning.”

“He told stories about all the war movies he’d been in,” recalled a doctor who asked his name not be used. “He also told the story that he had lost his hands in the war. He had his hair cut very short. He wore a hat and sharp clothes. Yes, people in Ysleta were impressed at first.

“He had another wife back then. I don’t remember her name, but I remember treating one of their daughters in the emergency room about 1962. Julian [the doctor used the Spanish pronunciation, hool-yon] said, ‘Don’t cry, honey, we’ll watch our TV in the car on the way home.’ He wanted everyone in the emergency room to understand that he had a television in his car.”

The doctor, a one-time Golden Gloves champion and a Korean War veteran, was a few years older than Julian Armas, but he recalled that “he was very active, real smart, he had his finger in every pie. No, he never played football at Ysleta, but he was a pretty good touch football player, even without his hands. He had a competitive drive even before he lost his hands.

“There are many people in Ysleta who think of him as a phony, and by most standards perhaps he is, but I don’t think so, because I understand the motive behind his behavior. I have respect for Julian. For most people, losing both hands would be the end of the show; for him, it was the beginning.

“The other things, the name change and claiming to be Italian, that’s compensation . . . not only for his physical handicap, which is really an asset to him now, but for the psychological stigma of being a member of the much persecuted and chastised Mexican-American minority in Texas, which can be a problem even to the most intellectual of minds.”

When you get down to it, the doctor said, Jay J. Armes isn’t all that different from Julian Armas. He was always a braggart. He always demanded center stage. He always had a need to achieve, and a need to exaggerate his accomplishments. If he sold fifty newspapers, he would claim that the figure was two hundred. Even now, when he apparently has the wealth to live anywhere in the world, he built a fortress for himself located less than a mile from his place of origin. Why not one of the silk-stocking areas, you ask. Why not Coronado Hills, a section of El Paso that he openly admired?

The doctor’s laugh was not sympathetic. He had a patient in the next room who manifested some of the same problems. This person had commissioned a sort of wood-carved Mount Rushmore in which his face appeared alongside Zapata, Villa, and Cortés. “The sine qua non,” the doctor said, “is a departure from reality.”

“Julian,” he said, “lives here in the Lower Valley because these are the people he needs to impress. In a better part of town the rich gringos would just look on him as another crazy Mexican.”

The Catholic church that Turner, Resendez, Julian Armas, and almost everyone else in Ysleta attended still stands, as it has since 1682. It was the first mission in Texas. From the Tigua Indian museum across the church grounds visitors can still hear recordings of the ancient ceremonial chants. Long before Europeans had crossed the Atlantic, the ancestry of these people—Julian Armas’ forefathers—had perfected a civilization that the flock at the Immanuel Baptist Church might not yet comprehend. This was the heritage that Jay J. Armes denied.

Almost everyone I spoke with in Ysleta who was anywhere near Jay J. Armes’ age, knew the story of Julian Armas. “He wasn’t tough,” a drunk Indian named Rachie told me, “but he was mean.” Rachie recalled Julian’s first job as a security officer—it was throwing Rachie and his friends out of the movie house where Julian worked. Rachie remembered how delightful it had been, shooting Julian in the head with chinaberries. Van Turner remembered the high school PE teacher made Julian take off his hooks when they played touch football. All of the old friends remembered that Julian liked to pinch the girls with his hooks. Or heat them red-hot in the popcorn machine at the movie house. One of his pleasures was heating up a 50 cent piece and throwing it to a younger kid. The doctor, Margie Luna, and several other eyewitnesses recounted the time he had his hooks in the popcorn machine and grabbed Rosalie Stoltz by the arm. You can still see the burn scar 30 years later.

A few years ago when Jay J. Armes ran for justice of the peace, he failed to carry his home district of Ysleta. The prediction is he won’t do much better running against Sheriff Mike Sullivan, who is also from Ysleta.

Mike Sullivan is half Irish and mostly Mexican. The people who know him think he’s a pretty good man. Until very recently Jay Armes professed to think the same thing.

Sullivan made his department’s criminal investigation division available to Armes, and helped Armes get appointed deputy constable last August, which is the reason Armes is permitted to wear a gun and maintain a siren and yelper on his limousine. Armes also claims to be one of three authorized Interpol agents working in the United States, but Sullivan has no knowledge of this.

Cynical talk has it that they are still friends, that Armes has volunteered his services as a stalking horse to ward off other potential candidates. Armes did this once before, in the JP race some years ago.

Whatever the motive, Armes sounds like a serious candidate. Lately, he has been speaking to labor and women’s organizations, telling how he could find Jimmy Hoffa in a few days if the price were right, and spreading bad tales about his old mentor, Mike Sullivan. He called Sullivan a “figurehead” who allows prisoners to walk in and out of jail as though it were a resort motel, who permits his deputies to beat Farah picketers, who hires ex-cons and homosexuals, who gives his inmates amphetamines, which are “the same thing as tranquilizers, and also known as Darvon.” But the most serious charge was serious, even by border-town standards. Armes accuses Sullivan of framing and even assassinating his enemies and credits several recent attempts on his own life to the Sheriff.

At the El Paso Club one afternoon when Armes was avoiding the crew from CTV, he struck up a conversation with a banker and an architect who were talking business at the next table. The El Paso Club is one of those phony-formal, itchy, squirmy private clubs frequented by movers and shakers, a place where you’re embarrassed to cough unless someone winks first. So it was that everyone in the room (except Fred, who was having lobster salad at the next table) looked up when Jay Armes began to speak of Mike Sullivan as “the first dictator in the United States, except J. Edgar Hoover.” He told the banker and the architect that Mike Sullivan was arranging small cells for his enemies, and when the cells got too small, he was arranging for them to be killed.

The banker puffed on his cigar and said, “I had no idea that situation existed.” Then, as though the question naturally followed, he asked, “How’s the TV series coming?”

Armes told them how his producer, Leonard Freeman, had leaned on 60 Minutes to help him get elected.

“How is the media treating you?” the architect, asked.

“I’m more worried about the press than anyone else,” the banker said. “If they can do it to the president, they can do it to anyone.”

“Don’t be surprised if a bomb goes off and blows me up,” Armes said. Then he shrugged with his hooks, smiled, and said, “But that’s life.”

On the street outside the El Paso Club, Armes stopped to campaign with three gnarled loafers eating pecans on the curb. They didn’t seem very interested. “I don’t vote,” an old man in a World War I campaign hat said. “I’m eighty-one. To hell with it.” Armes shook his head and walked toward his waiting limo. “Can you imagine what this country would be like if everyone had that attitude,” he said sadly.

Mike Sullivan refused to talk about his differences with Armes, except to say, “I knew the kid since he used to deliver my paper in Ysleta. I liked the kid. I helped him in many ways. Then something happened and he turned against me.” What happened was a disagreement over just how Jay Armes could use the El Paso Sheriff’s facilities. In the beginning, Sullivan had authorized his criminal investigation division to cooperate with Armes, and together they had solved some cases. Armes got the money, Sullivan pointed out, and most of the credit. From Armes’ standpoint, the biggest case involved the theft of some men’s slacks stored in the Lee Way trucking terminal. “We broke the case,” Sullivan said, “but the kid took credit, and Lee Way was pleased. They hired him to check out a terminal in Oklahoma City where some TVs and stereos had been ripped off. I told him to go up there and work the same way he did here—work with the sheriff. Sure ’nuff, the goods were recovered. That led to even a bigger contract. He made better than a hundred grand off of that.”

Then Armes became dissatisfied with Sullivan’s criminal investigation division and started demanding the use of patrol division as well. Getting Marlon Brando’s son back from Mexico had been a good lesson. So had his authority as a deputy constable to serve subpoenas. Joe Shepard estimated that the right to serve subpoenas was worth at least $10,000 a year to a private investigator.

“He wanted our patrol cars for cover,” said Captain S. J. Palos, one of Mike Sullivan’s officers. “It was the same trick he pulled when he recovered Marlon Brando’s kid. Brando’s attorney already knew where the kid was. Jay Armes crossed the river, hired a couple of gunsels and got him out of Mexico. There was a similar child custody case here in El Paso. He got one of our marked patrol cars to park outside the residence. After that, all he had to do was knock on the door and say, ‘I’m here for the kid. My backup is parked just outside.’ The rest is automatic.”

Captain Palos, a retired Army colonel, said, “Jay is not a scholar of evidence. We’ve had to reject several of his cases because the evidence just wasn’t there. It appears to me that he lives in a type of fantasy world. He reads an adventure story, and a week later he tries to relive it.”

“I liked the kid,” Mike Sullivan repeated. “He came back from L.A. in an old Cadillac convertible with a dummy telephone, all fired up to be a private detective. I told him then, ‘You do that work just like you do anything else: you take care of business, you do it by the book.’ I said, ‘You’ll be living off human suffering, you had better stay on a straight line.’ ”

I asked Sheriff Sullivan about the submachine gun that Fred the bodyguard carries. Sullivan told me it was an M-1, hammed up to look like a submachine gun. A hype. Just like the helicopter at the side of the house. The same prop rusted years ago in front of Kessler Industries until Armes acquired it and had it shipped to his place.

Captain Palos had an explanation for Jay Armes’ boast that he employs more than 2000 agents around the world, 600 of them in the El Paso office. There is an association of private detectives with about that number of members. They can all claim each other. “There are about 400,000 police officers in the United States,” Palos said. “Sheriff Sullivan, as a member of the National Sheriffs Association, could claim all of them as agents. I seriously doubt if Jay’s got two agents in El Paso, let alone 600. I have never seen them as long as I’ve been here. Put a pencil to it and figure up how much 600 full-time agents would cost a year.”

I did, using the mythical poverty line as a pay base, but the figure was so ridiculous I threw it away.

If this were a real detective story it would now be time to confront the suspect, and with him the reader. It would be the place to pull in all the facts and discard all the red herrings and wrap the whole package with a red bow. But there won’t be any neat red bows, because the true story of Jay J. Armes lies buried beneath the rubble of twisted stories, mistaken dates, and transposed facts: we may never know the true story, but it has little in common with what Newsweek and People and other periodicals printed, or with the B-grade plots and grand mystique that Armes projects for himself. The real story is of a Mexican-American kid from one of the most impoverished settlements in the United States, how he extracted himself from the wreckage of a crippling childhood accident and through the exercise of tenacity, courage, and wits became a moderately successful private investigator. There is more sympathy, drama, and human intrigue in that accomplishment than you’re likely to find in any two or three normal studies of the human condition.

Who really understands the agony of Julian Armas? He wanted much more: He wanted the hands and blue eyes of his self-portrait, he wanted to be in the movies, he wanted his life to be like the movies. Maybe he didn’t see the right movies. Maybe they didn’t show them in Ysleta, or maybe he wasn’t paying enough attention to see that the audience eventually woke to reality. What makes the story of Jay J. Armes, aka Julian Armas, so difficult to tell is precisely the Hollywood mentality in which nothing is what it seems, in which everything is an illusion.

There is no recourse then but to pare away the misstatements and exaggerations and attempt to fill in the blanks, but first I want to point out that I did not go to El Paso for the purpose of exposing Jay J. Armes. I had never heard of him until two days before I arrived, a bewildered guest, at his home. I hadn’t read any magazine articles or seen him on any of the TV talk shows or even heard the mention of his name, although I soon discovered that half the kids in El Paso and even Austin knew him as that dude in the hooks who can do karate. The reader has discovered Armes the way I discovered him, and if the first part of this story overwhelms you, imagine what it did to me.

As the reader may have guessed, they never heard of Armes/Armas at UCLA. They never heard of Armes/Armas or Professor Max Falen at NYU. If this classic father figure, this teacher who first recognized his student’s talents and took him into his own home, really is employed “as a sort of visiting fireman” in Armes’ Los Angeles office, then he too has a serious handicap. Neither Falen nor the office is listed. Neither Falen nor Armes has a California detective’s license.

The Federal Aeronautics Administration never issued a pilot’s license to Armes or Armas. The Academy of Motion Pictures has no record of a film entitled Am I Handicapped?, starring Dana Andrews or anybody else. Old friends speculate that Armes may have made some technical films illustrating expert command of hooks, but no one knows for sure. He did appear in one episode of Hawaii Five-O as a heavy named Hookman, but some people who know Armes and have heard the sound track believe the voice is dubbed. Armes claims the Library of Congress selected that episode as the “best show ever on TV,” an award the Library has never made or has any intention of making.

CBS isn’t filming The Investigator, as the El Paso Herald Post reported on November 29. That film crew that everyone supposed to be from CBS was a crew from Chicago doing commercial work for a toy company. A spokesman at CBS acknowledged that the series was a hot project of producer Leonard Freeman. But Freeman, the man Armes was repeatedly calling while I was there, died almost two years ago. The dog-eared script on Armes’ desk is owned by Lorimar Productions, but it is not an active project. It is one of hundreds of scripts mildewing in Hollywood.

There is a staff memo making the rounds at 60 Minutes suggesting a story on Jay J. Armes, but no decision has been made. Whatever the decision, it won’t help Armes to any election victory in January. The Democratic primary isn’t until May, of course, and the general election is in November, as always. The wonder of it all is that apparently Armes himself is so wrapped up in his own myth that he doesn’t realize what damage an investigative show like 60 Minutes could do to him.

There was, to be sure, a dramatic Mexican jailbreak using a helicopter which inspired the Charles Bronson movie Breakout. The only authoritative account of it, The 10-Second Jailbreak, does not mention Jay J. Armes. Armes takes credit for this oversight: he claims that the pilot who got the publicity was a soldier of fortune from Jamaica whom Armes hired to take the heat off himself. Otherwise, Armes says he would be arrested the next time he put a foot over the border and be forced to serve out the remaining sixteen years of his sentence. Who knows?

Law officers in El Paso believe that Armes did bring Marlon Brando’s kid out of Mexico, though they believe the circumstances were considerably less dramatic than the tale Armes spins. I saw a photograph of Armes and Brando, both exercising large smiles, but I also saw a photograph of Armes and Miss Universe. I couldn’t reach Brando for his version. The UN Plaza jewelry caper, which came after Armes’ recent spate of publicity, appears genuine, but there is no way to check the other claims—the Interpol connection, the third-degree black belt in karate, the glider caper into Castro Cuba, or the friendship with Howard Hughes; for that matter, Armes could have easily said he was a CIA agent or a UFO carrot farmer.

Of all those incredible tales, at least two are fairly accurate, and they probably say more about our junk-commodity society, counterfeit-hero mentality, and burned-out consciences than all the fantasies and delusions of a poor boy from the Lower Valley.

As for the obvious question, where does Armes get all that money if he’s not a big-time operator? I didn’t see evidence of that much money. When you check the El Paso city tax records, Armes’ “nine-acre estate” turns out to be 1.24 acres, although he does own 1.5 acres of adjacent property, as he claims. Most likely the net value of his estate is considerably less than the $1 million figure quoted in Newsweek (or the $1.2 million that he told me). The estimated replacement cost that appears on the city tax real estate card is $50,000. Armes paid real estate taxes last year of $476.13.

Armes probably did earn a nice chunk for the Lee Way security job, and there is convincing evidence he collected on an $80,000 settlement from a bizarre law suit against the American owner of a Juarez radio station who hadn’t paid Armes for his work in Mexico. Armes’ friends trace a big part of his personal wealth to his friendship with an eccentric and reclusive multimillionaire named Thomas Fortune Ryan, who has supposedly cut Armes in on some lucrative real estate deals. The Three Rivers Ranch on the backside of White Mountain in New Mexico, which Armes claimed to own, is in fact Thomas Fortune Ryan’s reclusory, although Leavell Properties picked up a purchase option a few years ago.

It is true that Jay J. Armes drives around El Paso in the damnedest black limo you ever saw, armed to the teeth. That pistol in his hook is the real McCoy; I watched him fire it. So is the loaded .38 on his left hip. Fred’s “submachinegun” might technically qualify as a submachinegun: anyone with a knowledge of weapons can rig an M-1 with a paper clip and make it fully automatic.

Of all those incredible tales, at least two are fairly accurate, and they probably say more about our junk-commodity society, counterfeit-hero mentality, and burned-out consciences than all the fantasies and delusions of a poor boy from the Lower Valley.

The Ideal Toy Corp. is marketing a series of Jay J. Armes toys, designed along the line of the highly successful Evel Knievel series. “It’s what we call our hero action figure,” Herbert Sands, vice president of corporate marketing, told me. “Batman and Robin, Superman, that sort of hero, but like Evel Knievel, Jay Armes is a real live super hero doing what he really does.” There will be Jay J. Armes dolls with little hooks for hands, Jay Armes T-shirts, a Jay Armes junior detective game. That film crew that the El Paso Herald-Post reported was shooting “The Midget Caper” with Armes and Mike (“Mannix”) Connors in November, was in fact doing a trade film for Ideal toys.

And Macmillan Publishing Company of New York does have a contract for the Jay J. Armes story. I talked to Fred Honig, executive editor of the general books division, who got the idea for the book after reading the article in Newsweek. Honig immediately flew to El Paso and arranged the deal. He wouldn’t confirm the price, but the contract I saw in El Paso revealed that Jay Armes would receive about $15,000 advance, and an extra-large break on royalties.

I asked Fred Honig for his impressions of Jay J. Armes.

He told me, “Here in New York we always think of someone from El Paso . . . in the wilds, you know . . . we think of them as being fairly unsophisticated . . . fairly unknowing of what’s going on. But this man is fascinating. Very quick, very intelligent, able to grasp problems and solve them.”

Yes, I thought, that sounds like Jay J. Armes.

What the Media Says About Jay J. Armes

According to People magazine, Jay J. Armes:

- Owns and pilots two jet helicopters;

- Commands million-dollar fees;

- Employs 2400 people around the world;

- Has clients including Elizabeth Taylor, Elvis Presley, Marlon Brando, and Yoko Ono;

- Is 42 years old;

- In high school won letters in track, football, and basketball;

- Was paid $80,000 in settlement for the loss of his hands when he was a teenager, money which he turned over to his parents and seven brothers and sisters;

- Earned a bachelor’s degree in criminology and psychology from UCLA in 1960;

- Lives on a million-dollar, nine-acre estate in a mansion with 26 rooms and an indoor pool;

- Has had eleven attempts on his life, including having his front tires shot off while speeding down the highway at 100 mph;

- Has eleven bulletproof cars.

According to Newsweek, Jay J. Armes:

- Keeps a loaded submachine gun in his $37,000 Rolls Royce as protection against the next—and fourteenth— attempt on his life;

- Lives behind an electrified fence in a million-dollar mansion;

- Is a skilled pilot;

- Made $25,000 in three days by finding Marlon Brando’s son Christian;

- Sent a helicopter to rescue an American from a Mexican jail, [an] exploit said to have inspired the movie Breakout;

- Made the football, baseball, basketball, and boxing squads as a kid—using a crude set of hooks in place of hands—before graduating at age 15;

- Earned degrees in criminology and psychology at New York University;

- Gives 10 per cent of his earnings to the Immanuel Baptist Church;

- Was shot in the chest five years ago by one of his thirteen would-be assassins, whom he managed to kill with a .22 magnum pistol imbedded in his right hook;

- Is 35 years old;

- Has signed to shoot a future television pilot for CBS entitled The Investigator.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- El Paso