This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

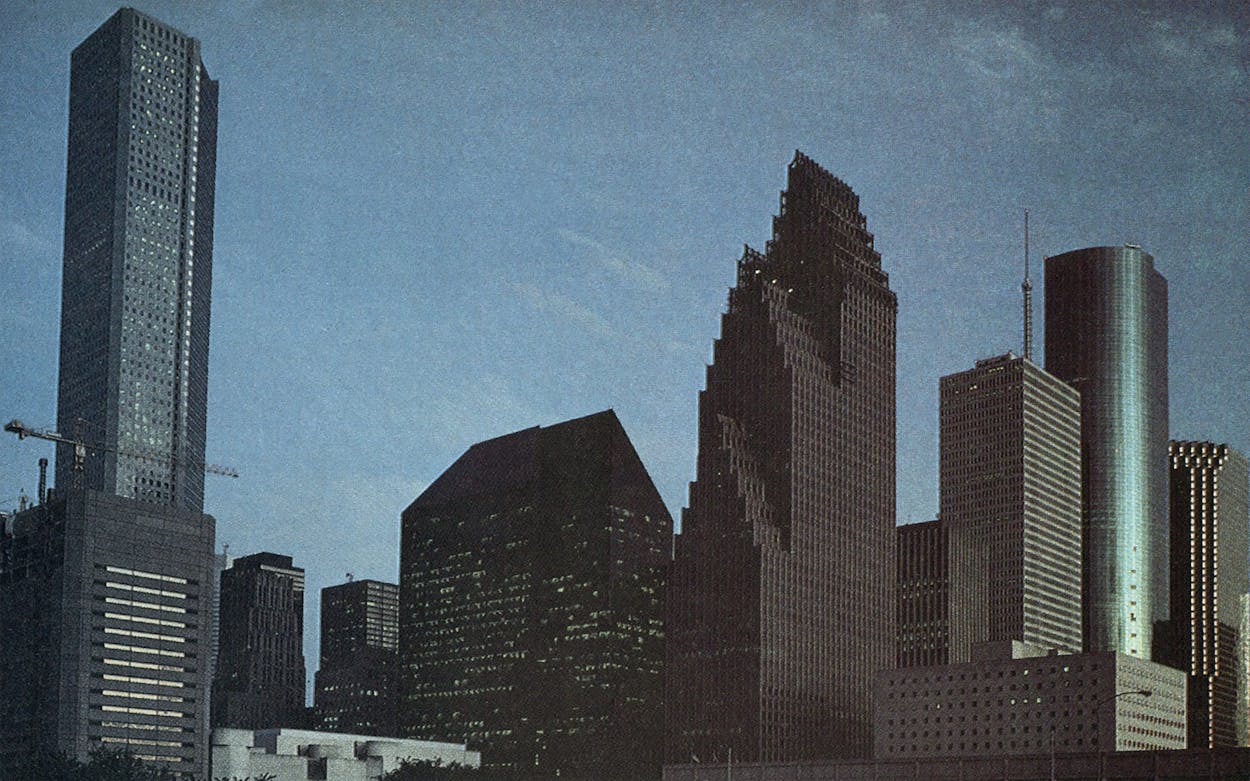

Skylines have always had a life of their own. It’s easy to recall those movies from the fifties that opened with the outline of Manhattan sketched in a single, uninterrupted notation, a kind of urban cardiogram. In the brief time since then, the architect’s pen has jogged to take in a whole new generation of designs. Houston’s downtown skyline has become nationally recognizable and nationally celebrated, and a stunning skyscraper going up now will assure its prominence for a long time to come; it has given a lacy, frenzied edge to the city. A second grand skyscraper, serene and aloof, is kicking off a whole new skyline in another part of Houston.

The Transco Tower, which was opened to tenants in December 1982, looks from afar like the kind of building Frank Lloyd Wright must have had in mind when he said that the only appropriate place for a skyscraper is out in the country. Visible from miles around, it appears as a lone lighthouse shimmering in the distance. Transco towers over a vast sea of stalled cars and squat buildings near the busiest junction in Houston—the intersection of Loop 610 and Westheimer. The building’s publicists say the 64-story tower is “the tallest building in the Southwest outside a central business district,” but those words hardly get at the impression Transco makes on a passerby. Its glass silhouette catches the eye and then holds it and holds it until you are miles down the road and the building has disappeared over the horizon. The Transco Tower, quite simply, is a building with charisma.

RepublicBank Center, which will receive its first tenants in October, projects an image that is as gregarious as Transco’s is solitary. It has taken its place downtown, on Louisiana Street between Capitol and Rusk, which is the architectural counterpart of Hollywood’s Avenue of the Stars, with Philip Johnson’s famous Pennzoil Place and Skidmore, Owings & Merrill’s One Shell Plaza, InterFirst Plaza, and Allied Bank Plaza all within a few blocks of each other. RepublicBank stands out in this distinguished crowd not for the usual reason—because of superior height—but rather because of its extraordinary shape. It looks like a Gothic cathedral that somehow broke the customary bounds in its reach for the sky. It has no flying buttresses or spring vaults, no fine tracery or stained glass, but it gives the impression that it should. Whereas the dominant material in most modern Houston skyscrapers is glass, at RepublicBank the first thing you notice is the stone; the building is sheathed in a roseate granite known as Napoleon red. And whereas most other modern skyscrapers emphasize their sleek lines, the RepublicBank building seems to go out of its way to be unsleek. Its stone is purposely rougher than most granite. It has dozens of prickly spires. Its three rooflines jut into the sky in a fashion that can only be described as jagged. The flights of fancy that RepublicBank takes imply much more than a fondness for Gothic architecture. Behind them is the message that RepublicBank is a radical departure from what has come before it in downtown Houston, as radical even as the landmark Pennzoil Place was when it was built eight years ago.

Both Transco and RepublicBank were designed by the architectural firm of Johnson/Burgee architects, home of America’s best-known architect, Philip Johnson, and both buildings were developed by Gerald Hines, who has left a larger imprint on Houston’s skyline than anyone else. Johnson and Hines have joined forces before—they completed Pennzoil Place and the beautiful Post Oak Central project together in 1975—and the combination has always had a certain magic.

Pennzoil Place was Johnson’s first foray into an architectural movement now called Post-Modernism, and with it, he “broke out of the box,” moving away from the rigid glass skyscrapers of the fifties, sixties, and seventies. Since the appearance of Pennzoil’s twin trapezoidal towers, however, Post-Modernism has come to imply a broader, more interesting rethinking of architectural style. Today the best-known aspect of Post-Modernism is the use of forms from the history of architecture that were eschewed by the modernists, who were seeking a timeless, “international” style. In recent years many skyscrapers have taken shapes quite different from the modernist box, but Transco and RepublicBank (on which Johnson and Burgee worked with the Houston firms of Morris-Aubry and Kendall/Heaton, respectively) are two of the first buildings to use the historical forms on a monumental scale. And since it is highly unlikely that a new skyscraper able to outshine Transco and RepublicBank will be built in Houston any time soon (especially now that the oil boom is over and office building vacancies are hovering around 20 per cent), the two buildings may represent the end of the great Houston skyscraper boom that began with Johnson and Hines and Pennzoil Place.

But as impressive as Transco and RepublicBank are, they can’t ride into immortality on the coattails of Post-Modernism or the oil boom. Flash and circumstance aside, the question of the buildings’ greatness is a troubling one; it looms over RepublicBank and Transco as much as RepublicBank and Transco loom over Houston.

Houstonians familiar with the San Jacinto Monument may have a clue to what makes Transco such an awesome sight. Off an obscure dirt road, out of the haze of the Ship Channel, the San Jacinto Monument rises above nearby chemical plants with a grandeur that is a little unnerving. It is a grandeur that comes from the monument’s sheer height in an otherwise commonplace landscape. So it is with the Transco Tower, rising above the Westheimer-South Loop area (it is nearly five hundred feet taller than the next-tallest building in the Galleria area). And, like the San Jacinto Monument, Transco is meant to be viewed in the round, as a piece of sculpture, from the freeways and streets that encircle it. From a distance it does not appear to have a front or a back, nor does it seem to have windows or divisions between floors. It rises straight up from the ground, like an obelisk, and looks no more habitable than the monument does.

Size is just one reason for Transco’s powerful appearance. Mirrored glass is the other. Except for the black, nonreflecting bay windows that streak up its sides, Transco is completely covered in mirrored glass. It gives the building an overall hard look—unlike that imparted by nonreflecting glass, which, because it absorbs light, gives depth to a surface. Reflecting glass excludes the viewer in the I-can-see-you-but-you-can’t-see-me style of mirrored sunglasses. And yet Transco doesn’t look arrogant, like the wearers of those sunglasses so often do; it looks solid, massive. That impression is bolstered by the six setbacks that cut into and narrow the skyscraper. Topping off the setbacks at the building’s summit, a double-pitched roof evokes the pointed pinnacle of the Washington Monument and underlines what is elsewhere abundantly clear: Transco is at least as much a monument as it is an office building.

In another age Transco would have been called a masculine building. “London is a man’s town/There’s power in the air” went the lines of the old poem. Hines’ promotional brochures claim that Transco’s references to past architecture “recreate the air of boldness and unabashed power.” This is an aesthetic that takes for granted great height, hard edges, unrelenting scale—1.6 million square feet—and most of all, harsh, reflective glass.

Transco’s bravado gives it a suave and even sophisticated presence. But skyscrapers must work on the ground level as well as in the clouds; when Transco stops being a monument and starts being a place where people work, its bravado gets in the way. Some effort has been made to connect the building with the everyday, mundane world. Tenants can walk to the Galleria through a wide skybridge, or they can eat lunch in the huge park still under construction next to the building. In the Transco offices, the corner spaces—the prestige spots in any building—have been reserved for secretarial pools so that more people can enjoy the views.

For all of this, however, there is still an odd litigation between the human factors and the monumental factors in the building. Nowhere is this tension more apparent than in the foyer. There, a two-story-high colonnade of massive pinkish-gray granite columns marches into the building until it is headed off by an absolutely blank granite wall of the same color. Except for two stripes of black granite, which follow the lines of the colonnade, the floor is gray granite, and all of the walls are of the same ponderous pinkish-gray. The entrance has about as much warmth as a tomb and about as much informality as a military troop inspection. It’s the kind of place where only Mussolini would care to linger. Anyone else would want to make a beeline for the elevators and the welcome relief of the colored marble that adorns each of the six cabs.

Outside, the problem is even more acute. Hines’ literature claims that the immense height of the tower is brought down to human scale by a “Presidential” entrance arch, contained within and seemingly carved out of a blocklike granite porch a mere ninety feet high! It had to be that tall to match the proportions and the spirit of the rest of the building, but it’s hardly what could be called human scale. It is difficult to see why such an entrance was needed at all, since visitors and tenants will enter the building through a parking garage.

Transco has been compared to the Chrysler Building in New York, the most famous of the early art deco skyscrapers, built during the late twenties and thirties. The buildings do have in common a kind of glittering presence, but Chrysler’s top, with its series of stainless steel arches, is too unlike Transco’s blocky top of squared-off setbacks to sustain the comparison. There is, however, another building in New York that is much more like Transco: the lesser-known Beekman Tower Hotel, designed by John Mead Howells in 1928. (Philip Johnson, in fact, can see it from his New York office window.) The Beekman Tower has stone where Transco has reflective glass, and its 26 stories are dwarfed by Transco’s 64, but the buildings are otherwise almost identical. Transco’s setbacks and bay windows even create a pattern of light and shadow similar to the pattern that plays across the Beekman Tower’s setbacks and vertical rows of windows.

Transco did not have to be so slavishly imitative to be a striking building. Even if the point of Post-Modernism is to reunite the old with the new, Johnson and Burgee have done it better before. Their nearly completed AT&T building in New York, with its now famous Chippendale top, is a more graceful combination of new and old and, as a result, is a more successful building. Johnson has talked about the influence on the AT&T project of Alberti’s Church of St. Andrea in Mantua, but even so, it is difficult to attribute a particular feature to any other building. Even the pedimental top has never before appeared on a skyscraper in the same way. Most of AT&T’s post-modern touches, like the raised public space on the first floor and the arcade that reaches out over the city sidewalk, are more subtle and integral to the building than the pedimental top is.

Transco’s shortage of originality is not likely to keep many people from being moved by it, but it might prevent some from pointing out this building as a harbinger of what is yet to come in Post-Modernism. It’s a shame that Johnson and Burgee didn’t take the creative leaps with Transco that they took with AT&T. But, in all fairness, it should be said that the area in which there is the most difference between the two buildings is also the area in which each works best. AT&T reaches out over people on the street because it is a good New York building; Transco dominates the sky in a way that is visible from dozens of streets and freeways because it is a good Houston building. And in this way, Transco, just as much as AT&T, affects people where they live.

“But a cathedral,” Marcel Proust wrote, “is not only a thing of beauty to be felt. It may, for you, no longer be a source of teaching to be followed, but at least it is a book to be read and understood.” When you see RepublicBank’s spires dancing on the Houston skyline, or curve around the city in a car and notice its three-tiered roofline turning with you, you can’t help but be glad that the book of Gothic cathedrals has been reopened.

In the glass and steel world of Houston’s modernist boxes there’s nothing like RepublicBank. With its tiers of pink Gothic spires rising higher and higher, it looks like petticoats among pants legs. And like the great cathedrals of rural Europe—Chartres and Reims—which hover protectively over their small hamlets, RepublicBank is both stern and familiar. Johnson considers his own encounter with Chartres (where his mother took him when he was thirteen) one of the most important architectural experiences of his life. He refuses to use the word “Gothic” to describe RepublicBank (he prefers the phrase “neo-northern Renaissance”), but whatever he calls it, his deep understanding and appreciation of the Gothic spirit come through in the building’s tower.

RepublicBank gives the impression of being a grouping of four buildings. One reason for this is that its tower setbacks are not just corner setbacks, like those of Transco, but rather setbacks that span the entire northern width of the building. This stairstepping (from 32 stories, to 47 stories, and finally to 56 stories) creates the need for three pointed rooftops instead of one. It also creates the appearance of three towers within a single tower. The banking lobby, in front of the tower, looks like another, or fourth, building. On the interior a dramatic six-story-high vaulted arcade connects the lobby to the tower from front to back, and a slightly less impressive north-south arcade forms a lateral connection. On the exterior, however, this second arcade comes between the two buildings, and because it prevents them from abutting each other at any point, it fosters an impression of detachment.

“I know which building RepublicBank is,” a recent visitor to Houston said. “It’s the tall building that looks like the little church next to it.” Well, not quite. But the buildings do have much in common stylistically. The rooftop of the banking lobby looks like what the roof of the tower would look like if it were not broken up by setbacks. It has the same tiers and the same spires marking its corner. Even the short, raised posts that run across the various tiers on the lobby’s roof like tiny attached fences echo the granite piers that stretch up the sides of the tower.

That these piers are in relief rather than flush with the windows, as is common in most Houston skyscraper designs, strikes at the heart of what is best about RepublicBank: it allows for a freer play of light and shadow, of form against form, than any tall building constructed in Houston in recent years. Only in the charming Niels Esperson and Gulf buildings, which went up in the late twenties, can Houstonians find comparable energy in the shaft of a skyscraper. Johnson says his building sparkles, and, his characteristic hubris notwithstanding, he may be right.

RepublicBank certainly wears its Napoleon red granite with a sprightliness not found in the nearby Texas Commerce Tower, which is covered in gray granite. Comparing that building’s use of the stone with RepublicBank’s is a little like comparing a gray tunic with a ruffled dress—the ruffles are a lot more fun to look at. The joints of granite and glass are so precise in the Texas Commerce Tower (designed by I. M. Pei) that the richness of the stone is downplayed and easily overlooked. But the Italian stonemasons working on RepublicBank were called on to accentuate the “stoneness” and tactility of the granite. To accomplish this, they varied the size and cut of the stone, which played different finishes off against each other. In the Renaissance it was popular for palace facades, like that of the Medici palace in Florence, to represent a hierarchy in stonework, with the roughest, most rusticated stones at the bottom, trimmed blocks with deep joints on the second floor, and completely smooth blocks with barely perceptible joints on the third floor. The stone of RepublicBank moves from the ground up in a similar progression. Large, honed blocks of granite rise up from the sidewalk to just about eye level. This fortresslike beginning is then met by a curved molding —called a bullnose—that juts out and marks the beginning of the second level. Here the surface is still rough because the granite has a hammered finish. Higher still, the granite has a flat, flamed finish brought about by heating it to high temperatures. The stones at this level are smoothly cut and closer together.

RepublicBank’s stone is nice, but it is not enough to make the lower portion of the building seem inviting. As in the Transco Tower, the enchantment of the building fades as you get closer to it. The entrance arch is monstrously oversized; at 125 feet tall and with more than a thousand pieces of granite, it seems to solemnly assure that RepublicBank will sanctify your banking needs. The building’s windows are the least inviting part of all. The first line of windows, on the street level, are mock windows, square niches containing blank slabs of granite; they have all the warmth of a fortress. The next two higher registers are real windows, but their only value is that they allow natural light to enter the upper regions of the banking lobby. Looking at RepublicBank, you get the feeling that you have to be a member of the church (or a customer of the bank) to be allowed in.

But once you are inside, the heavy and forbidding forms of the exterior dissolve into something uplifting—forms that seem weightless and shapes that appear to be made of light. And in a sense they are made of light; that annoying separateness between the banking lobby and the tower enables the skylight-filled rooftop of the small building to rise and fall in a complete gable shape before it becomes attached at the bottom to the bigger structure. Because of the profusion of light from the skylights, there almost seems to be no ceiling in this room. There is only a suggestion of the exterior tiers in an intricate, Piranesian latticework of interior arches and coffered designs (all painted white).

This space did not get to be so wonderful without overcoming a few obstacles, the most difficult of which was nothing less than building around an entire existing structure. Because a northeastern portion of RepublicBank’s building site contained the Western Union building with its millions of wires that run all over the world, Hines was faced with either moving the equipment, at intimidating expense, or working around it. He solved the problem by constructing for Western Union a new customer office on the corner of Fannin and Gray and by completely enclosing (except for a doorway on the outside of the building) the old offices within the vast dimensions of the lobby. Maybe that’s why the ground floor has no windows. So effectively obscured from view is the Western Union building now that it seems to have been built out of existence. It is hard to believe, but the roof of Western Union is now the floor of the banking lobby’s northeastern mezzanine.

Certainly not all of the design victories were of such staggering proportions; there are many small touches that make the banking lobby an especially appealing place. Gensler and Associates/Architects of Houston have worked with Johnson and Burgee to find just the right placement for teller’s booths and office furniture. And Gerald Hines has purchased a 1914 four-faced street clock, each face of which is five feet in diameter. When it is set in place at the intersection of the two arcades, it will be visible from all directions and is bound to give the whole room something of the feeling of a medieval town hall. Oddly, though, the floor may suggest such a feeling more than anything else does. Although not all the white and Napoleon red granite slabs of its inlaid design have yet been installed, the sound of shoes on the concrete floor already echoes through the immense lobby. It is a sound peculiar to the great cathedrals and public spaces of Europe, and it is a reassuring reminder that you have not been overwhelmed by the architecture.

It is doubtful that New Yorkers Johnson and Burgee thought in terms of bringing a sense of culture to Houston when they gave RepublicBank a Gothic design. But its appearance there and its general success do signal the beginning of a shift in the image of Houston. The city’s extraordinary assortment of modern buildings has long told the world that Houston is a place of culture, but the variety has also conveyed that it is a city with no real caring about what has gone before. Transco and RepublicBank, by drawing so heavily on the past, may begin to change that, and that’s all to the good.

But architects should be careful not to rely too much on the past. If they don’t filter old ideas through their imagination, they are likely to set a trap for themselves that will become more confining than the rigid walls of Modernism’s box ever were. Great works of art—whether they be operas, novels, or buildings—have the deep resonance that comes not just from critiquing and reinterpreting what has gone before but from absorbing it so thoroughly that when it emerges it does so subtly, almost imperceptibly. This is what separates the truly classic from the merely fashionable. Both RepublicBank and Transco would have benefited from a more rigorous distillation of the old ideas that shaped them. Perhaps their postmodern links with the past should have gestated a little longer before bursting from the heads of Johnson and Burgee like Athena from the forehead of Zeus.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Architecture

- Houston