THE COURAGE OF A BOY CHILD in Texas is equated with his balls. It’s a crude metaphor, but it declines to go away. Male Texans are supposed to be rough, tough, and ready for whatever comes down the pike. In the 1830’s the makers of this myth gave up the relative safety of life in the United States and, allied with a few independent-minded Mexican settlers, risked all they had on reports of well-watered timberlands and prairies that billowed in the wind like ocean waves. When the Mexican claimants to that wilderness turned out to be bullies and despots, why, Texans licked their army and kicked them out without help from anybody. And then we beat back the ferocious Indians who had denied the Spaniards and Mexicans real settlement of their Texas province for 150 years. At all costs we stood our ground. It’s a rousing story, though in the mythological version significant details get left out. As a birthright, it’s dangerous, and as a code to live by, it’s horseshit. But who would we be without our myths?

I WAS BORN IN THE ABILENE hospital the evening of March 18, 1945. Daddy put a fair-sized crimp in my boyhood while I still looked scalded. At least Mother claimed the name was mostly his idea. There are fads in naming babies like fads in choosing breeds of dogs. Just after the war, great numbers of American couples named their babies Jan. It was my bad luck that about 99 percent of them were daughters. Many people have since assumed my parents were sophisticates who gave me the European name, pronounced “Yahn.” It’s common throughout Scandinavia and Central Europe—there are Czech national heroes named Jan out the kazoo. But nope, Daddy didn’t know beans about Europe. He just thought it was a handsome name. I never really blamed him. It’s not like all those parents of the baby boomers got together and had a mass consultation. Still, I would be a grown man before I could shrug off some lout sneering, “‘Jan!’ That’s a girl’s name!”

My memories of my earliest years are indistinct and few. The images took on sharpness and sequence when Daddy hitched a trailer to his new black Chevrolet and we made the move to Wichita Falls. It was 1949. We first lived in an apartment house downtown. The units opened onto a central hall at the end of which was a single bathroom that all the tenants shared. Mother and Daddy hated that. Daddy was consumed with building us a home. He bought a lot on a new street called Keeler that was just four blocks from his dad’s broad-porched house on Collins.

Though he always voted with labor and the Democrats, my dad was a conservative man. He wanted my sister and me to grow up exactly the way he had. He planned for us to go to grade school at Alamo—built with a brick facade that resembled the iconic Texas fortress—just like he had. Our friends would come from families similar to ours. But Daddy miscalculated: By three blocks, he learned after buying the lot, Keeler was in the district of Ben Franklin, a new school built near the mansions of the Country Club area. I started school with kids whose dads were oil millionaires.

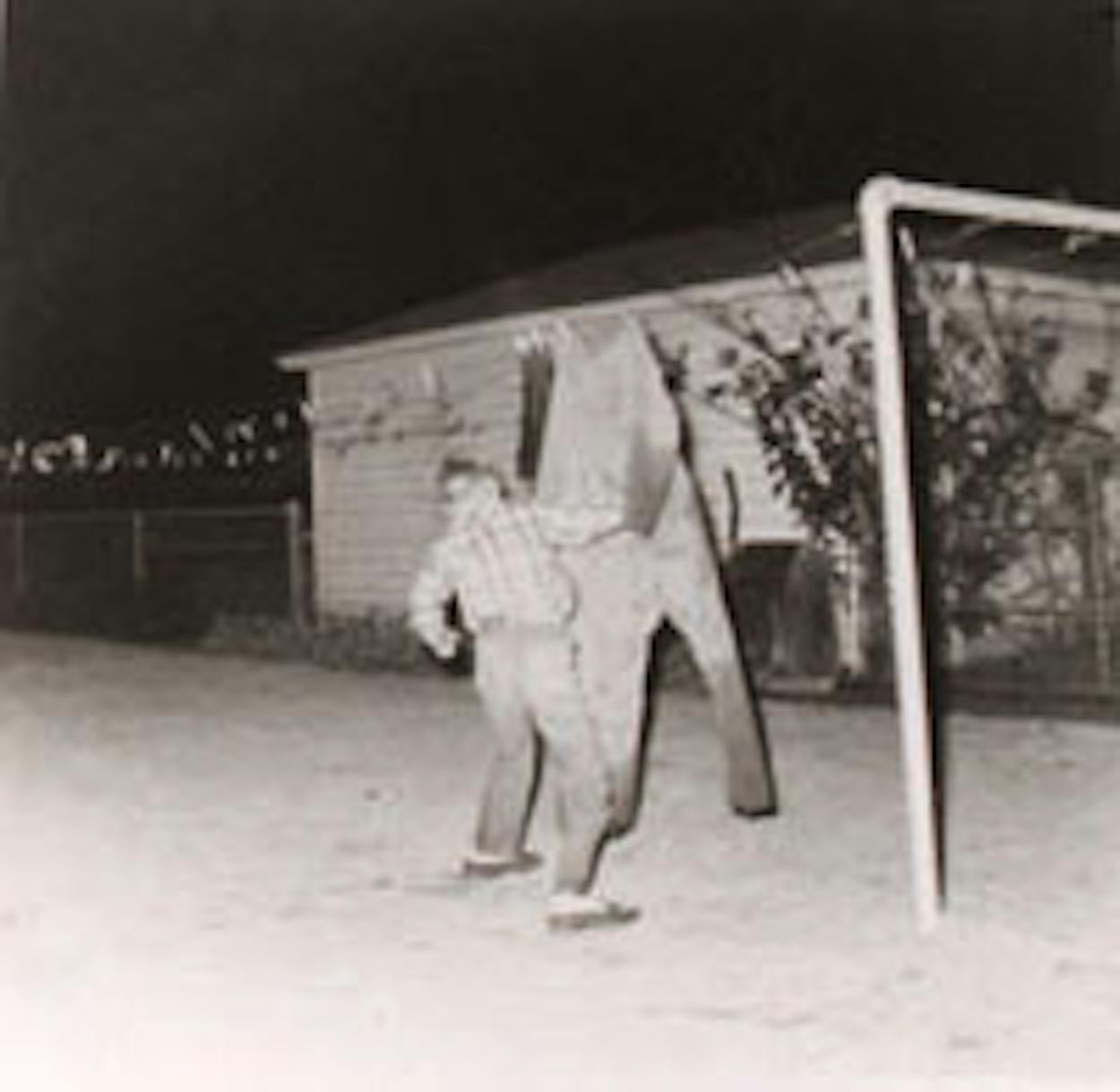

My name wasn’t the only problem. I was skinny and had buckteeth. Other kids at school mumbled through a mouthful of braces; I looked in the mirror and saw Bugs Bunny. I was unsteady of emotion and thought I was ugly. We were blue-collar middle class, but I thought we were poor. Once I was proud of my dad’s ’48 Chevy; now it embarrassed me. Every morning in front of the school there was a line of Cadillacs. I was uneasy when my mother took a job in a laundry. Why was our own wash hung out on clotheslines in the back yard? Why didn’t we have a washer and dryer like everybody else? At the refinery Daddy wore thick one-piece cotton garments called coveralls. Drying on the lines, they hung in beheaded mannish forms, twisting their arms in the constant breeze. At night I would square off with the coveralls and pound them with my fists. My mother and sister thought it was funny, and they took snapshots of me doing it. I wasn’t pretending to get back at Daddy for some wrong. I think it was more like my first boxing gym. I was trying to work out the anger and fear in my head and turn them into bravery and skill. For sure as sundown, I was going to have to fight.

The fights took place after school in vacant lots and were great fun unless you were one of the fighters. For me they fell into a pattern. I would back up while my opponent walked forward with his fists raised and his friends jeered me. Finally I’d run forward spewing shrill jabber and throwing windmill punches. I lost more fights than I won, but a couple of times my outbursts were so furious that bullies decided to leave me alone. I got in trouble, I eventually noticed, when I started the fights. One foe, Danny Mulligan, was a dark-haired pretty boy who must have been born with a smirk, and he ran with the real toughs. I could be pushed around by that bunch, but I was not afraid of Danny. His scorn of me pissed me off, and I called him out one day right beside the Ben Franklin flagpole. We fought until I staggered around blindly, feeling the blows whang off my head but just not believing the outcome. Finally Danny dropped his hands and said, “Boy, do you want me to make soup out of you?”

IN A TOWN WHERE ATHLETICS WAS everything I was a nobody. I came into my teens when Wichita Falls was enjoying its run as the state’s kingpin of high school football. Our Coyotes reached the state finals four years in a row and won the title twice. I couldn’t play football worth a flip, but I wasn’t smart enough to walk away from it. I hung on, riding the bench in the games and getting run over by bigger and tougher boys in practice, until a broken collarbone relieved me from a second tour with the B-team. I alienated an assistant coach who managed the baseball team in the spring, so I didn’t get the chance to show off my real love and modest talent, playing the outfield. Another coach’s invitation to join the track team ended badly; I hadn’t the wind or the discipline to run the mile. I quit in a particularly self-demeaning way—pretending to get tripped up by a competing runner, taking a fall in the hard, sharp cinders, just to put an end to it. I heard the coaches’ unsympathetic murmurs, about how I used to fake being hurt in football. Daddy tried to pass on his love of golf, but it bored me. All right, bone up for the college entrance exam. Do something constructive. Learn to play the harmonica. But the winter before graduation two friends dared me to join them in a dramatic alternative: boxing.

Joe Haid was the poorest of my friends. His father had died when he was little, and his sweet-natured mother provided for them by working in a grocery store. But Joe was always first at something—reading Kerouac’s On the Road, getting up at five in the morning to throw newspapers near the country club so he could buy a Cushman Eagle motor scooter that he painted metallic chartreuse, moving on to a pink ’57 Chevy that we drag-raced on Kell Boulevard to the limits of its 283 horses and four-barrel carb. Joe found a black man on the east side who would buy us bottles of Southern Comfort and cherry sloe gin. The parents of Joe’s girlfriends always hated him. Joe and his mother scraped together enough money for him to spend his seventeenth summer at the Culver Military Academy in northern Indiana, and he returned to us a boxer. He was sort of an effete boxer at first—the footwork they taught him resembled that of fencing—but he was fast with his hands and eager. Wayne Hudgens was a tall, strong rawboned kid who was game for anything. I was the nervous and glum one in the back seat.

I remember clearly my first awareness of boxing. It was 1953 and I was eight years old. I was playing on the floor of my Shelton grandparents’ farmhouse, and their console radio brought on the heavyweight title bout of Rocky Marciano and Jersey Joe Walcott. The exotic names gripped me. Then in the static the bell rang, soon the announcer started shrieking, and in seconds it was over, a first-round knockout. Wow! Rocky Marciano. Radio was the perfect medium for boxing; imagining most fights was far more exciting than seeing them. Six years later I jumped around my bedroom and whooped and danced out in the back yard throwing punches when Ingemar Johansson bombed the senses out of Floyd Patterson. Mother came to the kitchen window and stared, wondering what had come over me. Movie theaters showed films of the big fights along with cartoons and newsreels then, and to learn the magic of Ingo’s right—his “‘toonder’ and lightning,” his “hammer of Thor”—I watched a Kim Novak picture repeatedly so I could study every move of the fight on the big screen. An usher finally shooed me out.

Johansson had little else, but he made the straight right hand look simple. With a dip of the right knee, his shoulder, arm, and glove shot out in a perfectly straight line—down the pipe, in the jargon of the game. With a look of near boredom, he knocked the heavyweight champ down seven times in one round, and like a robot Patterson kept getting up. But I had just a year of hero worship for the dimpled Swede. In their second fight Patterson knocked him so cold that for a dangerously long time the only part of Ingo moving was a quivering foot. There is no rational defense of boxing. It regularly maims and kills its contestants, and the professional business of it is a rotten mess. But I couldn’t help myself. From the start I loved it.

Doing it, though, was another matter. In someone’s yard we occasionally laced up gloves and sparred. I found that my only reliable defense was to keep sticking my left hand in the face of the other guy. The jab came to me naturally. But throwing a straight right was not as easy as it looked, and hooks and uppercuts required pivots and timing that were beyond me. To box you had to be in tremendous shape. The real mountain climb, though, was overcoming your fear. Golden Gloves tournaments were well attended in Wichita Falls. The newspaper gave them good sports-page coverage, and sometimes there were radio broadcasts. Amateur fighters didn’t wear headgear then, at least not in Texas. You climbed through those ropes almost naked: More than injury, it was a fear of public humiliation. Worse than any of that was the torture of the “chairs.” To get ready for a boxing match you needed to be up moving, breaking a sweat, and maybe banging your own jaws a few times to get the adrenaline flowing. But even at the state tournament in Fort Worth, fighters had to sit quietly in folding chairs beside their opponents. Every time a fight ended, they stood up together and then sat down in the next folding chairs. Did someone decide that that instilled sportsmanship? What could you possibly say? Then some man led the other fighter away, and you climbed through the ropes in the red or blue corner, looking at a boy who all at once was an enemy, and the light was as intense as that of an August sun. And if you weren’t ready to go when the bell rang, the noise would fade until the only sound you could hear was the thump of gloved fists on your bare head.

Joe Haid researched the teams and declared that we should box for the Pan American Recreation Center. The gym was fashioned from the players’ clubhouse of an abandoned minor league stadium called Spudder Park. It had speed bags, a heavy bag, jumping ropes, and not much else. The coach was a laconic man who listened as Joe explained how the Culver instructors had taught him to slide his right foot forward as he was throwing his right; that way he was poised to follow with the sweeping left hook. “Sailor told you that, huh,” the coach grunted. “Get you knocked on your can, that’s what. You’ve gotta set your feet beneath you.”

One day he passed out medical release forms for our parents to sign. It amazes me now that he was going to let me fight the next weekend. I didn’t even know how to wrap my hands. All I had done was thump the bags a couple of afternoons and run some laps around the old baseball park. I guess he was of the school that you learn by being thrown in the fire and that referees know when to jump in and stop a mismatch. Or maybe he was trying to run me off. The challenge thrilled me. This wasn’t really sport; it was a fistfight, and if ever there was a way to stand my ground and prove myself, this was it. But as the tournament approached I lay awake at night certain that my fear and the ritual of the chairs would freeze me. When the bell rang I would just stand there, skinny, pale, and rigid, broken out with acne, as some boy ran across the ring to knock me out. Yet I wasn’t about to tell my friends I couldn’t go through with it. Then one day my dad stopped me in the hall when I came in from school. He had the release form in his hand. “Your mother,” he said gruffly, having lost the argument, “she doesn’t want you boxing. Find something else to do.”

Saved! But secretly I was ashamed; I thought I was still hiding behind her skirts. Joe and Wayne ragged me about it, but they knew my mother—when she said no she meant it. Mother later said she put up with the unpopularity in the household because she’d cringed for years every time a fastball sailed near my skull; she’d gone to get me out of a hospital when I’d suffered a broken bone playing football, and boxing was just too much. But I always thought her veto of boxing was more than the simple fear that I might get hurt. It was a moral issue. She knew that violence stirred in that guise easily spills into the street.

THUGGERY IS APT TO FIND its way out, no matter how it’s stirred. I was engaged by history and English classes in my first year at the hometown college, now called Midwestern State, but my parents didn’t have the money to send me away to school, and I resented that. Living at home, I felt like I was missing the college experience. Impressed by the uniform and the tan of a friend who had come home on leave, I enlisted on a whim in the Marine Corps reserve. The recruiter was a tall, thin gunnery sergeant. His calculated indifference was effective. “It’ll make a man out of you,” he told me with a shrug.

Six months later I was back in Wichita Falls with thirty more pounds and a hair-trigger temper I’d never possessed before. Half a year of being harassed and brutalized will do that. Of course, the Marines were in the stated business of tearing us down and making us into certain kind of men—men who would kill and risk getting killed if ordered to. Military life fit me not at all, but ironically, my impulsive bolt into its ranks proved to be my way out of Vietnam. The Gulf of Tonkin episode happened while I was in boot camp, and as the ensuing conflict raged, the warmakers decided it would cost them less political capital to fill the divisions with draftees than to call up the reserves. For six years all I had to do was show up at weekend drills and two-week summer camps. And that’s all I did—show up.

The oil had played out around Wichita Falls, so the refineries shut down. Daddy looked for another job and couldn’t find one, so he took a company transfer to Mount Pleasant, a small town on the edge of the East Texas pines, and my parents made their home there for thirty years. Living in the house where I had grown up, I attended the college, worked at a seed-and-feed store, and slouched through the Marines’ requirements of my time. I doused too many nights with booze, and sometimes I went looking for trouble.

One Saturday night I found it in Denton, where I was visiting my boxing pal Wayne Hudgens. Outside his apartment I slung my leg over a motorcycle. I was just sitting on it. But from a balcony a collegian yelled, “Hey, you! Get off that bike!”

I glanced over my shoulder and fit my hands around the handlebar grips. “Sorry, Pazz,” I mocked him, whatever his name was. “I was just admiring it.”

“Get your ass off.”

“Oh, now, Pazz.”

“I mean it. Get off. It’s mine!”

“Sure thing, Pazz. Fine bike you’ve got. Roomba.”

There was a thunder of footsteps on the walkway and stairs above. I wandered into Wayne’s kitchen and grew aware of loud male voices at the door. “No, no,” someone said. “We want ‘Pazz.'”

On the kitchen counter was a steel utensil that the brewing industry’s pop-top aluminum cans have made obsolete. Liquor stores used to give the beer openers away; we called them church keys. Gripped inside a fist, the hook made a nasty weapon. The uproar out there wasn’t Wayne’s problem. I swept up the church key and lurched outside to deal with these yahoos.

I wouldn’t have taken half the beating if I’d gone out there empty-handed. As the punishment continued, I said some dreadfully stupid things.

“I’d like to do this again with the gloves on.”

“Are you a Kappa Sig?”

I guess I wanted to slip him the grip.

Some boys never get over the horseshit years. They’re rednecks in fact and toughs in their minds the rest of their lives. But if you’re lucky, you become someone else.

The morning after that fight in Denton, with a wretched hangover I gazed in a mirror and took long stock of myself. Under one eye was a perfectly formed shiner. I wasn’t just embarrassed that I would have to go to class and my job looking like that. I was horrified, disgusted. With that church key I could have put that boy’s eye out—disgraced my family and gone to prison for maiming him.

Man, grow up, I told myself. And in that regard I did. I didn’t throw another punch at a man in anger for 32 years.