This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Five working men and a union officer huddle around a conference table in a room at the Ramada Inn near Houston’s Hobby Airport, playing nickel-ante stud. Down the hall three company executives, who long ago cast off their coats and loosened their ties, are calculating the costs of meeting the union’s demands. In the hallway two federal mediators stand ready to carry messages between the two caucus rooms. Today is the tenth day of contract negotiations between Olin Corporation and Local 367 of the OCAW (Oil, Chemical, and Atomic Workers International Union), which represents hourly workers at the Olin plant in nearby Pasadena. Though the current contract expires at midnight, progress is stalled as time runs out. Nobody expects anything different. “We have to negotiate right down to the wire,” an OCAW official says, “because otherwise, no matter what we come out with, the men will say we could have got more if we’d stayed in longer.” Twenty minutes before midnight the mediators recommend that the clock be stopped until the night’s talks are finished. The union men wearily agree.

Roy Barnes, the head of Local 367’s bargaining team, already knows about how far the company will go in the Ramada talks, because he has studied the outcome of recent Olin negotiations with other locals. He also knows that Olin’s Pasadena workers are in no position to force an exceptional settlement. The company’s fertilizer plant is too small to put a dent in multinational profits. During the past nine months Olin has laid off 50 workers at Pasadena, and only 330 are left on the payroll—a number small enough to make recruiting strikebreakers merely an inconvenience. Barnes knows that eventually his men will have to accept far less than the $1.25-an-hour increase they sought when the talks began; already they have reduced their stated goal to $1 an hour, and privately Barnes would settle for 85 cents. His men have no leverage; even though they make a full $1 an hour less than hourly workers at the nearby Shell refinery, they haven’t struck since 1949.

By midnight the union men are tensionless and bored, waiting for the company to respond. The answer comes at 3:30 a.m.: Olin insists on holding increases to 60 cents an hour. But Barnes knows this is not the final offer; Olin granted more to Louisiana workers last February. The men return to their card game.

At 10:30 a.m. the two sides reach an agreement. Olin offers an increase of 75 cents, a dime less than the union men swore they would accept, but they take it. At the union hall that night, Barnes tells the workers, “Men, this isn’t the best contract the OCAW has, and you all know that. But it’s the best we could get by talking. We either take it or we hit the bricks.” Only a dozen hands go up in opposition; the new contract is accepted. Roy Barnes shakes his head and sighs. He doesn’t like losing; he doesn’t like bargaining from weakness. He remembers that the big one comes up in January, when the Shell contract expires. It will be different then. Maybe.

At night from afar the mammoth Shell petrochemical complex on the Houston Ship Channel looks like a fairyland. Up close it seems like . . . Hades. Flames leap thirty feet out of hissing flares into the smoky orange sky, and on the ground, shadowy figures drag about with their shoulders hunched, as though Satan already had them in his chains. Pipelines and tubing spread across the ground and entwine in steel lattices overhead, forming a metallic jungle where workers often seem to lose their way. Smoldering distillation towers spit out wet steam, creating a foggy atmosphere that hovers over the complex. Pockets of the plant reek of sulfides and ammonia, and the roar of giant compressors sets off vibrations everywhere.

When the sun rises, the managers gather in the soundproof, vibration-free administration building, the only brick structure of any size inside the plant gates. They run the largest refinery in the Shell system, the plant that produces a third of Shell’s national output—a responsibility they share, however grudgingly, with Local 367 of the OCAW.

Petrochemical plants are ideal recruiting grounds for labor unions. Their surroundings are somber and overwhelmingly impersonal; the work is at times dangerous, at times tedious. The OCAW is a strong union, and Local 367 is strong at Shell. That strength is due for a severe test, however, in the months ahead, for most Shell contracts with the OCAW expire on January 9, 1979. If the rhythm of past OCAW walkouts means anything, 1979 should be a strike year. The last walkout was in 1973, and only once has the union gone more than six years without striking Shell. The likelihood of a walkout is enhanced by the belief of OCAW leaders like Roy Barnes that strikeless unions atrophy.

Roy Barnes is one of the most powerful men in Texas, though it is unlikely that many Texans who work more than two miles from the Houston Ship Channel have ever heard of him. He is the secretary-treasurer of Local 367 and its sole salaried official. Eight petrochemical firms in the area have contracts with the Local, and the men Barnes represents are responsible for 10 per cent of the state’s petrochemical output—and Texas produces more than a quarter of the nation’s petrochemical goods. In addition, Barnes is chairman of the OCAW’s Shell policy committee, which determines the union’s nationwide strategy against the company, including, of course, strikes. If Roy Barnes leads his men off the job, the whole nation will feel it.

Although past performance points toward a strike, a lot has changed since Local 367 last walked out on Shell. Previous strikes against the company occurred before the Arab embargo, which makes them ancient history in the petroleum industry. Many of the hourly workers who struck with the OCAW in 1962–63, 1969, and 1973 have retired. Most of the 2300 hourly workers on Shell’s Deer Park payroll today are under thirty, and, as unionists put it, have never “hit the bricks.” In terms of race and sex they are a far more diverse lot than their predecessors, and, though they have joined the union and have no fondness for company management, they also have a more relaxed and affluent lifestyle that may not bend to the discipline of a strike. No one can predict how the new generation will respond in a prolonged strike, not even veteran OCAW leaders like Barnes. If the OCAW walks out in 1979, the union could be plunged into turmoil, with the older membership struggling to maintain control. Or the strike could weld the union together in a way that meetings and exhortations cannot.

A crisis between generations is common to many unions today, but nowhere is it more evident than in the petrochemical industry. From 1941 to the end of the Korean War, demand for petrochemical products surged with the incentives of war and an expanding economy. By the mid-fifties, however, the market leveled off, and at the same time automation began to take its toll. Shell started laying off workers in 1958; the labor force at the complex, which in two decades had increased fivefold to 3000, was cut to 1500 by 1963. Because the union protected workers with seniority, most of those who got the ax were younger employees. Even after the layoffs, management felt the industry was still oversupplied with labor, and a bitter eleven-month strike starting in 1962 failed to persuade them otherwise. By 1970 more than half the refinery hands in the U.S. were between the ages of 50 and 55—Roy Barnes’ bracket—and the statistic held true at Deer Park. Then the embargo changed everything.

In 1974 Shell began a $1 billion expansion project at the Deer Park complex, which will diversify production and considerably increase plant capacity when construction is completed later this year. Some new units are already into operation and payrolls are fat again. Since 1974 Shell has created 600 new jobs for hourly workers; meanwhile, 200 hourly workers have retired and another 350 have been promoted to salaried ranks. More than half the plant’s hourly workers were not on the payroll four years ago; three-fourths were not at Shell in 1970. Yet their plant supervisors and union leaders are all nearing sixty.

Age is only part of the difference. Before 1968, blacks at Shell worked in one segregated department. Shell employed very few Mexican Americans at Deer Park between 1938, when Mexico nationalized Shell’s holdings south of the border, and 1965, when the company put equal opportunity guidelines into effect. Today, however, 18 per cent of the plant’s hourly employees are black, 8 per cent are Mexican American, and nearly 6 per cent are female.

No one is more concerned about the implications of these changes than Roy Barnes. Barnes resembles Ernest Borgnine and, like the actor, seems too big to fit comfortably indoors. Barnes came to the Houston Ship Channel from Oklahoma in 1948, working first as a construction hand, then for fifteen years as an hourly worker for Shell. In 1970 he passed up a pension from Shell to run for the job he currently holds. Even company men acknowledge that he is well suited to leadership. Barnes speaks softly and with studied consideration, like a priest. Nothing about him hints at Teamster sleaziness. He doesn’t have a police record, nor does he tote a gun. He says he has never pummeled a strikebreaker, and veteran union members say that he has always rejected any recourse to sabotage suggested by striking workers. Yet no one speaks of Barnes as the kind of insipid leader often found in the labor movement these days—the aptly named “business agent” of building-trades locals, who beams when he reports that he has never gone on strike and boasts that his children have graduated to medicine or engineering. Roy Barnes trudged a picket line for eleven months in the 1962 strike, and his son gave up an engineering job for a higher paying hourly slot at Shell. In union financial affairs, so often the source of corruption, Barnes has a reputation for openness and honesty. When I asked him how much he earns, he had to look up the figure: just under $28,000, which is roughly what he would be drawing at Shell had he not left. In the process, he let me see the books, not exactly the behavior one anticipates from a union boss.

Like a career soldier who believes the Army needs a war every so often to keep in shape, Barnes thinks strikes are necessary to keep a union alive. “A man needs to be in at least one strike to get a good education in unionism,” he says. But most of Local 367’s younger generation have not yet walked a picket line and many have little desire to. They rarely vote in political elections, either, and most do not see why they should. “A man has to be about forty before he can really participate in his union, his church, or his community,” Barnes told me. But he knows that the OCAW can’t wait fifteen years for the new workers to reach maturity. The deadline comes in January.

Petrochemical work is a lot like guarding a prison. Most jobs at Shell are sedentary. The workers keep watch on pressurized, highly volatile products. The prison guards’ main worries are that their charges will escape or revolt; petrochemical workers’ primary concerns are seepage and explosion. While moving crude oil or distillates from one compound to another, refinery workers open and shut valves, just like guards handling cellblock gates. They routinely inventory the contents of tanks and look for cracks in the walls, but between tasks they simply sit, sometimes reading or playing cards on the sly. They can be reprimanded for idleness or gaming, or ordered to perform make-work jobs. Foremen with bully mentalities often take advantage of the intermittent nature of the workers’ duties, if only because ordering men around relieves their own boredom. It is not surprising that the chief complaints of petrochemical workers are that there is too much harassment from the higher ranks and that job assignments are made on the basis of favoritism.

To these complaints add the issues of job safety and workman’s compensation and it becomes apparent why workers join unions. Indeed, the union got its start at Shell in 1933 after negotiations broke down over demands for, among other things, a new ambulance, gas masks, and compensation for widows of men killed on the job. By 1935 union organizers had signed up 80 per cent of the plant’s six hundred hourly employees. Despite forty years of union activity, federal regulations, and a 1973 strike over working conditions, on-the-job accidents are still common enough to warrant both company and OCAW safety crusades. Two Shell pipe fitters were killed in a 1976 explosion, and two other workers were severely burned in a flare-up last spring.

Wages, of course, remain an issue, but earnings at Deer Park are attractive: a base rate of $9.23 an hour for an operator, which adds up to $19,240 a year. Unskilled laborers like janitors make $7.50. Most workers can count on overtime or night pay to push their take over $20,000, and the union will be after more in January. As one younger worker put it, “The company is making more profits these days, so we’ve got to make sure we get better wages. Getting our share of the pie is what the union is for.”

There are more subtle reasons why people join the union. The union gives workers today what lodges gave their grandfathers fifty years ago. It has a hall where they can meet, shoot pool, and call each other by titles like “committeeman” and “chaplain”; it also gives them lapel pins, pencil clips, and matchbooks with insignia, just as the Elks and Odd Fellows do. In short, it provides a feeling of solidarity and a sense of identity. The union, like the lodge, also imposes its own code of ethics. One Shell veteran told me about a co-worker who broke the picket line during the 1962 strike; no one would speak to him after the settlement, and fifteen years later the strikebreaker is still ostracized.

Whatever their motives for joining, 95 per cent of the eligible hourly workers at Shell are members of the OCAW—a noteworthy statistic in a right-to-work state, where Texas law prohibits making union membership a condition of employment. Dues aren’t cheap: $18.50 a month, or a little more than 1 per cent of base pay.

In other unions, a man of Roy Barnes’ rank might call all the shots, but power in the OCAW is more diffuse. Barnes is the dominant figure during contract talks and on all large policy issues. He is an authority on everything from carcinogenic chemicals to the fine details of every OCAW contract in the industry. But the daily union work at Shell—usually grievances against foremen and complaints about safety—is handled inside the plant gates. At the base of the union structure are 112 shop stewards, 9 of them women, who handle minor grievances and recruit for the union. Above them and far more potent is the workmen’s committee, which formulates contract demands, bargains with management, and calls the Local out on strike.

Ten unionists, five from the chemical plant and five from the refinery, sit on the workmen’s committee, which meets every Thursday at the Local’s office on South Tartar in Pasadena. The committee processes grievances that cannot be settled by stewards at the shop-floor level, and committee members meet monthly with management teams. The presence of a committee member is also required under the current contract whenever Shell calls a worker on the carpet.

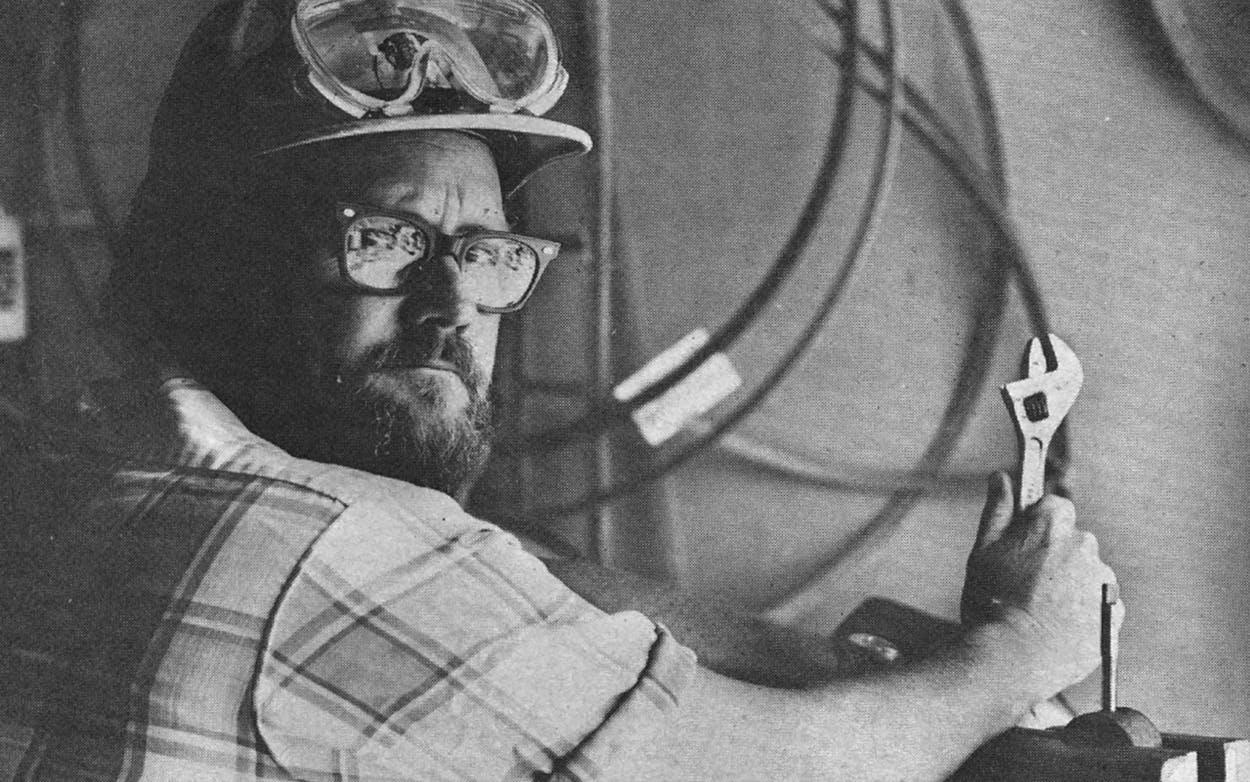

Everyone on the committee has been a member of the Local for at least eight years, which means all are strike veterans. Six are in their late thirties or forties and consequently provide a link between the men of Roy Barnes’ generation and the unseasoned work force hired since 1974. One of these men in the middle is John Patterson, 37, whose slender build, red face, curly hair, and full beard make him resemble a lanky Falstaff. Patterson is said to have ambitions for higher union office, and his personal tastes suggest a fondness for compromise. Like the older generation, he often wears pointed-toe cowboy boots; like the younger men, he is partial to pastel T-shirts. The older crowd is notorious for its affinity to pickups. Patterson drives a Malibu, but, like his older peers, he is a devout Bible reader. His musical preferences run more to rock than to country and Western, and he reads contemporary fiction in addition to the Scriptures.

Patterson grew up in nearby Galena Park but now lives in Pasadena. His father was a nonunion construction worker who was killed in an on-the-job accident. A few days after Patterson was hired by Shell in 1968, Local 367 walked out. Though he had not yet joined the union, Patterson honored the picket lines.

“By then I had enough experience with companies to know what unions are for,” he said. “And I’d been at Shell long enough to know that without a union I wouldn’t want to stay there.” Three years ago he was elected to the workmen’s committee, and since then union work has taken up most of his spare time.

Patterson is a good example of the transformation occurring in today’s union membership. He is a step removed from the men of Roy Barnes’ generation. I talked to a recent Shell retiree named R. C. Blair who came to the Ship Channel in 1948. He’d been a barber in Throckmorton, northwest of Abilene, before World War II, but when his postwar income didn’t measure up to his expectations, he headed for the city in search of industrial work. To his delight, he found not just a job but a niche. “It was just like home,” he recalled. “We were all just ol’ country boys and ex-GIs.”

Today’s Shell worker is more likely to have grown up along the Ship Channel than in West Texas. Many are second-generation industrial workers. Though Pasadena superficially reflects a cowboy image, it is an industrial suburb to its core, a blue-collar town that has more in common with Dearborn, Michigan, than Abilene.

The more union members I met—affluent young whites, women intensely aware of their minority status, radical blacks—the more I was struck by their remoteness from Roy Barnes and the union men of his era. If Patterson is one step removed, they have taken several leaps. That doesn’t mean they are in open rebellion to Barnes’ leadership, but it does mean that they have different values and don’t necessarily share his reverence for union, church, and community. I found myself wondering as I visited in their homes whether such diverse people could hold together under the stress of a long strike.

When Karl Marx said that workers had nothing to lose but their chains, he reckoned without men like Pat Kelly. Every workday morning, 27-year-old Kelly leaves his $23,000 Pasadena home and climbs into a Datsun 280-Z for a twenty-minute drive to Shell. It is true that older unionists have known a degree of prosperity (R. C. Blair could cash in his home and four rent houses for about $150,000, an average net worth for refinery workers his age), but few of them pursue the good life with the fervency of Pat Kelly.

When I visited Kelly, he was reclining on his Herculon couch, dipping Skoal from a round tin and spitting it into an empty milk carton. A dishwater-blond beard hid part of his face, pink-tinted sunglasses shielded his eyes, and his pastel T-shirt displayed the name of rock singer Jackson Browne. Soft rock music was playing on the stereo.

Pat Kelly grew up in Pasadena. His father was a union worker at Shell until the 1962 strike, when he quit to take a job overseas. After high school, Kelly enrolled at local San Jacinto Junior College, even though he never cared much for academics. When he drew a high number in the 1969 draft lottery, he decided to turn in his books and go to work. Shell hired him as an operator, a job that requires shift work. Each 24-hour day is divided into a daytime, evening, and late-night or graveyard shift, and workers spend about a week on each, with two days off between shifts. At the end of this cycle, they get four days off. Roy Barnes told me the men enjoy shift work because of the mini-vacation; this may be true of family men, but younger unmarried workers dislike it because they are on the job many weekends and nights. Because of the company’s seniority system, Kelly spent four years on shift duty. As soon as he could, he applied for a pipe fitter’s job, involving days only. The change probably pleased Shell as much as it did Kelly, because his attendance record quickly improved. “I didn’t think twice about calling off if I had plans for the weekend,” Kelly said. “Shift work tears up your single life.” Shift workers get a pay premium for evening and graveyard shifts; consequently they average $100 a month more than their colleagues who work only straight days and no overtime. Kelly, however, didn’t mind the pay cut. He earns about $20,000 a year, and after his house payment there is still plenty left over for his all-important social life. He spends his leisure playing poker, hunting, fishing, and carousing with other plant workers who, like him, are unmarried and prosperous.

Kelly did not attend the union meeting at which workers voted to strike in 1973, but he did not complain when walkout orders came. “I had enough money saved up that I didn’t mind it a bit,” he shrugged. “It gave me a vacation. I partied for four and a half months and that’s about it.” But the strike wasn’t just a lark for Kelly. He says that he first thought about unionism while walking the picket line. “I never gave it much consideration before. Belonging to the union was just something I did because the older men wanted me to. But when you’re out there on the picket line and those scabs go through the gates like nothing is going on and don’t even look up—it gets to you. They’re going in there, getting your job, and getting your money. That’s enough to make anybody burn.”

Six months ago, Kelly volunteered for an opening as a union steward in the pipe-fitting shop. Even in his new capacity, Pat Kelly is not all that Roy Barnes would have hoped for in a union member. He rarely attends steward’s meetings or other union functions and he despises politicians and does not vote; he does, however, contribute to the OCAW’s political war chest and, as steward, he sells the lottery tickets that fund it. But he adamantly ignores OCAW’s continual exhortations to go to the polls: “Two years ago, I did volunteer work in a local election and got all of politics I need. I don’t like anything about politics. It’s just like the plant without a union. Who gets elected is whoever has the most money or the most pull or does the most brown-nosing. Politicians are just like foremen.”

In lifestyle and political cynicism, Kelly is firmly in the ranks of the new generation, but in his feelings toward the company, he is a thoroughgoing union man. If anything, he disdains foremen more than politicians. They are salaried workers, the lowest rung on the management ladder, and though many are former unionists, the promotion sets them apart. “I’ve seen too many guys ruined by it,” Kelly says. “You make them foremen, and suddenly they think they’re different. I wouldn’t be a foreman for any amount of money. I can be myself the way I am now.”

Last spring Mary Anderson, 27, another Shell hourly worker, made plans to attend a “safety dinner” to celebrate a year’s work without a lost-time accident in her department. Shell policy allows employees to bring dates to such activities, and Mary did not want to miss the party. When Pat Kelly transferred into her unit, she decided to ask him out. Since then the two unionists have been dating.

Mary, whose father worked for Sinclair, is a second-generation refinery hand like Pat. Before she came to Shell, she worked at the usual women’s jobs—typist, Dairy Queen attendant, Fotomat clerk. She doubled her income when she came to Shell two years ago. Reasons beyond money brought her to the job. “I went there to lose weight. I wanted to do something energetic, and I have. When I started, I weighed 165. Now I’m down to 135. I’ll probably stay at Shell the rest of my life.”

Mary does not take easily to unionism. “I have a hard time seeing what it’s good for,” she says. But she is not as outspoken as Vickie Schmelzle, a tank-farm worker. “I joined the union, but against my will. If you’re not in the union and you get in trouble, you won’t get any help from the other workers. They won’t look out for you unless you’re in the union.” Like Pat and Mary, Vickie has never voted; unlike them, she has also declined union appeals for political contributions. She even ignores meeting notices. “I don’t even know where the union hall is,” she told me. Vickie Schmelzle was the only Shell worker I spoke to who didn’t know who Roy Barnes was.

Before starting at Shell eighteen months ago, Vickie was a vocational nurse. Her new job gives her certain luxuries nursing did not afford: she goes camping on long weekends and has taken up photography. She keeps her nursing certification active “in case of a strike” and also because she is hesitant about making a career of refinery work. “For one thing, I have chronic bronchial inflammation from breathing fumes. For another, I am finding that plant work is not so different from nursing. One of the reasons I quit nursing was that there was so much backstabbing and gossip among the women. I never knew men were the same way until I started at Shell.”

The attitude of Shell women toward the union seems to depend on how well they’ve been accepted on their jobs. The harder they’ve had to fight for acceptance, the more likely they are to support the union. Mary Anderson earned approval without turning to the union. “Sometimes there’s a lot of teasing and butt grabbing,” she said. “You’ve got to learn to put a stop to it.” Mary’s job required driving a forklift, loading 460-pound resin drums onto pallets. It tested her five-seven frame, but she refused offers of help. “What is most important to the guys on the job is that everybody do his own part. A woman at Shell can get guys to do her job, but that’s not good for”—she stumbled over a phrase that did not come easily for her—“well, I guess you might call it women’s liberation.”

But sometimes doing a job right is just not enough. Dolores Miller says the union saved her job: “I had one foreman who made it very clear he didn’t think a woman belonged out there. He wanted to take me to the gate [union slang for getting someone fired]. The union got me removed from his unit. Women are stronger members than men, because we know we’re out there by the grace of somebody besides the company.” A staunch union partisan, she is a steward and a telephone volunteer at election time. Her resentment of male workers, who, she says, “have to be taught to behave,” has touched off two moves to recall her as steward. Both failed.

Sexual discrimination is undoubtedly a touchy subject, and could get touchier, but race is the issue that could tear the union apart. It has once before: in the eleventh month of the 1962 strike, a rumor circulated among black workers that Shell would concede to the union’s economic demands if the union would agree to promote blacks into skilled jobs. The blacks, who were then confined to unskilled work, decided that the union was prolonging the strike not to win economic demands but to maintain segregation. Thirty black workers crossed the picket lines to demonstrate their lack of faith in the union leadership. Fifteen years later, the barriers against blacks in skilled jobs have been eliminated, but lack of faith among black workers is as strong as ever.

In two years as an OCAW machinist, Oran McMichael, 27, has raised the ire of union leaders on numerous occasions. As he refinished a floor in his newly bought South Houston home, he told me why: “I haven’t been afraid to say what I think of the union’s policies. The union has not really tried to include blacks. They’ll take a grievance on anything but discrimination. If they get one, they may take it, yeah, but call it something else.”

His differences, McMichael claims, are not with white co-workers, but with the union leaders. “Race relations are really at a new point. Whites invite blacks over to their homes after work and vice versa. It’s usually pretty stiff and formal, and the friendships usually break down after a few visits, but at least the effort is being made. A few blacks have moved into Pasadena, and they haven’t met the hostility that we expected. Things are getting better.”

Last year McMichael led a dozen blacks and Mexican Americans to a union meeting with a demand that the Local censure Shell for slowness in promoting minority workers. Roy Barnes opposed the measure, which also called for a program aimed at improving race relations within the union. The proposal failed, but ten of eighty white workers present voted with McMichael.

McMichael also assails Roy Barnes and the OCAW for routinely endorsing Democrats. “Younger folks are seeing the swindles and scandals that have come out since Watergate, and that’s one reason why they’re turned off politically. The other big reason is inflation. The union is misleading folks by saying the Democratic party is all we have. Union leaders won’t call for the formation of a party that is really in the interest of working people.”

McMichael is a member of the Trade Union Educational League, which he describes carefully as “an organization that stands for the interests of all working people.” It could more accurately be described as a socialist labor group. Organized labor in this country, despite a leftish public image, is in many ways quite conservative, not at all like European unions that band together to form socialist political parties. The OCAW constitution forbids membership to communists—an undefined term that at other times in American history has been broad enough to encompass whatever and whoever its detractors wanted. In the years just after World War II, Local 367’s leaders secretly cooperated with an FBI informer whose job was rooting out radicals at the Shell plant, and since that time there have been no open communists or socialists in the union. One steward warned me that McMichael was convinced the OCAW hated blacks and that he was “probably a communist,” a term he seemed to use as a convenient synonym for “radical troublemaker.”

In other times and other unions, Roy Barnes and his cronies might have moved to expel McMichael. Instead, they have decided to tolerate him in the interest of avoiding racial strife. McMichael recently won election as a shop steward on his unit, with the support of white co-workers, and the Local issued certification papers under Barnes’ signature without delay or protest. “Now that Mr. McMichael is a steward,” Barnes says, “we are hoping that he’ll take a different attitude.”

McMichael has also had second thoughts about his approach to Barnes. “I don’t think we’ll ever agree about a lot of things, like union democracy and politics. But it’s in the union’s interests to keep all its members united, and Barnes knows that.”

And McMichael is right. It is political attitudes that most sharply divide the old and new memberships. Despite the differences in sex, race, and lifestyle, there is little question that the younger members are pro-union and that they support the notion of striking.

Roy Barnes believes that the union has two weapons at its disposal: politics and striking. An autographed portrait of Ralph Yarborough hangs in his office. But the younger members of Local 367 wouldn’t vote for a Ralph Yarborough or anybody else. They have lost the faith of their fathers in the political process. Striking is the only weapon they have confidence in; if anything, they are more strike-happy than their elders.

Nonetheless, Shell executives are not particularly frightened by strike talk. They see a 1979 strike as an opportunity to test the OCAW in new circumstances and, possibly, to weaken it. Most of them would like to believe that union power in the petrochemical industry has crested and will now decline.

“In the past few years, the OCAW has won larger wage gains than many of us in management thought were justified,” says Deer Park employee relations chief Dave McClintic. Shell would like to halt that trend in 1979 and it has other objectives as well. “This Local bargains hard on a variety of issues besides wages. So we are now looking at the current union contract to see what restrictions in it we might want removed,” says McClintic. Talk of “removing restrictions” does not sit well with Roy Barnes. “I wouldn’t put it past Shell to provoke a strike if it wanted. An untimely strike could hurt the union,” he says.

A short strike would probably be good for Local 367. It would give the green recruits a picket-line education and would pull members into union meetings. Even if they won only minimal concessions, the strike would affirm the faith expressed in the old union song: “The boss won’t listen when one guy squawks, but he’s got to listen when the union walks.” It would establish the new generation at Shell as a work force not to be tempted.

But Local 367 can’t determine how long a nationwide strike will last. If all OCAW locals with Shell contracts walk out together, workers at Deer Park cannot return to their jobs until national demands are met locally. Further, if the OCAW walks out, it gives Shell the option of forcing the strike into extra innings. Strike funds are limited. Roy Barnes estimates that the OCAW nationally and Local 367 could provide only about $20 per week for no longer than five months. Economic hardship might force some workers to cross picket lines or seek other employment.

But most would not. Local 367’s younger generation, despite its inexperience and material comfort, should not be regarded as soft. The union’s newer members may spurn politicians and second-guess their union leaders, but only a few give credence to Shell. Their fathers sought and found prosperity in the refineries, but they take affluence as a starting point for their economic lives. They do not compare their standard of living with Depression-era poverty; they look not to what was but to what could be. They know petrochemical firms are doing well and they want a share of Shell’s good fortune. The attitude typical of the younger worker at Deer Park is described in Ecclesiastes: “The sleep of a labouring man is sweet, whether he eat little or much: but the abundance of the rich will not suffer him to sleep.” Shell’s second-generation workers are restless, not because they are poor, but because others are rich.

- More About:

- Energy

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Houston