In May of last year, Lance Armstrong was riding in the Pyrenees, preparing for the upcoming Tour de France. He had just completed the seven-and-a-half-mile ride up Hautacam, a treacherous mountain that rises 4,978 feet above the French countryside. It was 36 degrees and raining, and his team’s director, Johan Bruyneel, was waiting with a jacket and a ride back to the training camp. But Lance wasn’t ready to go. “It was one of those moments in my life I’ll never forget,” he told me. “Just the two of us. I said, ‘You know what, I don’t think I got it. I don’t understand it.’ Johan said, ‘What do you mean? Of course you got it. Let’s go.’ I said, ‘No, I’m gonna ride all the way down, and I’m gonna do it again.’ He was speechless. And I did it again.” Lance got it; he understood Hautacam—in a way that would soon become very clear. It’s a story Lance likes to tell, and for good reason. If there’s one thing that sets him apart from the dozens of elite cyclists he has beaten in the past two Tours de France, it’s that he trains the hardest of all, especially in the spring, when he and the team he leads, US Postal Service Pro Cycling, ride up and down the Alps and the Pyrenees. He calls these rides a trade secret, something that no other team does; they’re a major part of a rigorous training program. Lance quite possibly wants to win more than anyone else in the world.

In May of last year, Lance Armstrong was riding in the Pyrenees, preparing for the upcoming Tour de France. He had just completed the seven-and-a-half-mile ride up Hautacam, a treacherous mountain that rises 4,978 feet above the French countryside. It was 36 degrees and raining, and his team’s director, Johan Bruyneel, was waiting with a jacket and a ride back to the training camp. But Lance wasn’t ready to go. “It was one of those moments in my life I’ll never forget,” he told me. “Just the two of us. I said, ‘You know what, I don’t think I got it. I don’t understand it.’ Johan said, ‘What do you mean? Of course you got it. Let’s go.’ I said, ‘No, I’m gonna ride all the way down, and I’m gonna do it again.’ He was speechless. And I did it again.” Lance got it; he understood Hautacam—in a way that would soon become very clear. It’s a story Lance likes to tell, and for good reason. If there’s one thing that sets him apart from the dozens of elite cyclists he has beaten in the past two Tours de France, it’s that he trains the hardest of all, especially in the spring, when he and the team he leads, US Postal Service Pro Cycling, ride up and down the Alps and the Pyrenees. He calls these rides a trade secret, something that no other team does; they’re a major part of a rigorous training program. Lance quite possibly wants to win more than anyone else in the world.

Two months later, in the middle of the 2000 Tour de France, French journalists thought they had found another secret of Lance’s. A camera crew for the France 3 TV network filmed two men from Lance’s team leaving their hotel room with several bags of garbage and putting them into a car. The crew followed the car for the next few days and eventually filmed the occupants throwing the bags into a roadside trash bin sixty miles from the hotel. After the car left, the crew opened the bags. What they found—bloody compresses and empty medicine packaging—looked suspiciously like evidence of doping. To the French media, though, everything Lance had done in the past year had looked suspiciously like doping.

The video wasn’t broadcast until November, after the French police got hold of it and a full-scale judicial investigation of Lance was under way. What got the prosecutor’s attention was evidence of Actovegin, a legal substance considered by some to have the same performance-enhancing capabilities as an illegal one, erythropoietin, or EPO, the drug that has turned cycling upside down over the past decade. Some athletes use Actovegin in conjunction with EPO. A French court would eventually order urine and blood samples taken from Lance during the Tour to be analyzed. The ensuing attention would get so ugly that Lance would consider not racing in the 2001 Tour. “We are absolutely innocent,” he said not long after the story broke. “It’s just weird. When you take into consideration that we’re not even talking about a banned substance, and the fact that the inquiry is so late, something’s not right.” It turned out that the camera crew from state-run France 3 had been shadowing the US Postal doctor for days. To the head of USA Cycling, the whole prolonged mess was clearly a witch-hunt. To French fans and sportswriters, things weren’t so obvious. “Why throw your garbage away on the highway?” they asked. “What are you trying to hide?”

Lance has fought the French before, and won. Indeed, the 29-year-old just plain likes to fight—it’s why he’s alive today. Lance beat cancer; he beat death. Then he went out and won the Tour, the hardest race in the world, inspiring anyone who ever dreamed of transcending physical despair. He became an icon, a corporate brand, known by his first name, an American hero whose whole life has become a parable, personifying everything we like to see in ourselves—courage, perseverance, triumphing over adversity, winning through sheer grit and grace. Who isn’t moved by the images of Lance riding up a mountain with a look of absolute determination on his face, standing stoically with other cancer survivors, raising his baby son aloft in exultation, or parading victoriously through the streets of Paris? Lance seems chosen.

Across the pond, people see things quite differently. It takes more than pluck and guts to win the Tour de France, they say. It takes performance-enhancing drugs, and Lance is no different from anybody else. He’s a doper, a drug cheat. “If he isn’t a doper,” says British writer Andrew Jennings, the author of The Great Olympic Swindle, an account of corruption and drug abuse at the Games, “he must stand almost alone in his sport.” Accusers—from an award-winning Irish journalist to a muckraking Frenchman and an American doctor—have no proof but plenty of circumstantial evidence. They say cycling has lost its soul to doping; Lance is their Antichrist, a man whose significance they resent and whose protestations of innocence they mock. The French complain the loudest (the France 3 allegations are still unresolved). Twice now the brash American has won their national prize, and in all likelihood, this month he’ll do it again. “An American looks at my story,” Lance told me, “and says, ‘Hell, yeah, of course he did it. He’s motivated, he’s crazy, he’s passionate.’ A French guy, he says, ‘C’est pas possible’—it’s not possible. The stigma there around cancer is what we had probably thirty years ago.” In Lance’s distinctly American way, anything is possible if you want it bad enough. That, say his accusers, is the problem.

Riding With Lance

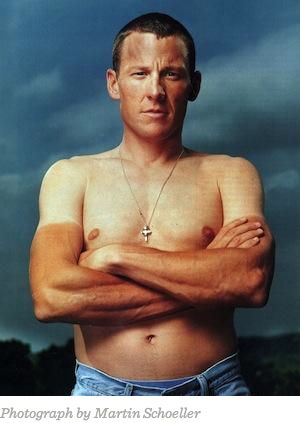

Like most of my countrymen, I’ve never taken cycling seriously. The sport is so European, and damned if we’re going to like it just because we’re supposed to. Guys in silly outfits riding bikes in places like France—how tough could that be? I asked Lance if I could ride along with him to see for myself. I ride my bike to work every day, I told him, and I’m in decent shape. Warily, he agreed. It was early April, and he was in training for the 2001 Tour de France. He showed up at the rendezvous in Austin precisely at ten on a yellow bike and in his thin, blue US Postal jersey, black shorts, helmet, and cleated racing shoes. He looked like a giant bug. He’s about five foot ten, with sinewy arms and legs, which are shaved so it’s easier to pull gravel out of his skin after a crash. His calves swell with the soft curves of hard muscle.

We headed east on a busy crosstown street, cruising side by side at a brisk pace, or so it seemed to me. Indeed, I was soon at the limit of my 21 gears, pumping and breathing hard. We turned and hit our first long, slow climb and I began puffing harder. Lance, of course, breathed normally. He began playfully asking me questions about a weekly Austin newspaper; I answered in gasps, cursing him under my heaving breath. “How fast are we going?” I sputtered. “Not fast enough,” he said with a laugh. It was pretty damn fast—about 18 miles per hour. Lance said that if this were a regular training ride, we’d be going much faster.

We talked mechanics and equipment; well, he talked, I puffed. He showed me the small computer monitor on his handlebars that displays wattage, revolutions per minute, speed, gear, time, distance, pedal cadence, and heart rate. When he gets home, he’ll download it all into another computer. Lance is an information addict. His gears, he showed me, are in his brakes, at his fingertips. With a bottle of water on the frame, he had everything he needed and knew everything he needed to know.

We hit another long incline, and I could feel my stomach begin to churn as my legs pumped as hard as they could. It felt like a melon was bursting inside me. I asked him about the latest issue of some cycling magazine that wrote about one of his rivals, Jan Ullrich. “Who’s on the cover?” he asked. I wasn’t positive, I huffed, but I thought it was a Spaniard. “He’s an American or he’s a Spaniard?” Spaniard, I blurted. He reached out his hand and, smiling, said, “Michael, I’ll push you,” and put his hand on my back. I felt like I was being pulled up the hill by a rope. The panic in my belly disappeared. “What do you mean he’s a Spaniard?”

At this point I decided he looked less like a giant insect and more like a superhero. In truth Lance has spent the better part of the past decade turning his body into a machine and himself into a robo-rider. His body was already an amazing instrument. In high school, testing revealed he had an extremely high VO2 max level—his body processed more oxygen than most people’s—and further testing done by Ed Coyle of the Human Performance Laboratory at the University of Texas at Austin showed that his body produces little lactic acid, the stuff that makes your muscles burn, tire, and give out. His cardiovascular system also sends more oxygen to his muscles than that of most athletes, although, Coyle says, “I don’t find him to be such a unique specimen among elite cyclists. I think he works very hard and knows how to focus and peak.” Lance focuses relentlessly on the peculiar details of the science of winning. He has a strict diet and weighs his food before eating—his pasta at night and the next morning his muesli, soy milk, even the banana. He tries to avoid beer when training. Lance is a slave to calculation, whether he’s figuring the stroke of his legs, the slope of his shoulders, or the shape of his helmet and whether he’s doing it in a wind tunnel or on a stationary bike wearing electrodes. All to get that extra second or minute. Or six.

Lance talked about teams, how, although riding a bike is a solo activity, cycling itself is a team sport. His eight US Postal teammates work for him, literally (the French call the support riders domestiques). “Normally I’ve got a couple of guys who just stay with me,” he said. His teammates are there to protect him—from enemy cyclists (who will try to isolate him and wear him down) and, usually, the wind. Lance showed me this on a last unholy hill, riding to the front and the side, blocking the gusts, which were blowing at 15 miles per hour. “That’s just me in front of you,” he said. “Imagine seven guys. It makes a big difference.” What about the sprinting, when you break away from everyone and leave them in your dust? “That’s only the last five or ten miles of the stage or race. I’m not doing anything until that point. The team leader should never be out front in the wind. If he is, that means the race is at a really critical moment, and it’s down to one on one.” Which is the part he likes best.

We stopped at an intersection somewhere way out east, and it was obvious that my learning experience was over. His training ride, a light one that day, was maybe a quarter done. Later, over beers at a popular bar on Lake Austin called the Hula Hut, I asked him about the latest drug allegations and his war with the doubters. “It’s a war I will never win,” he said. “Even if they found a foolproof test for everything, which I would love, these guys are always gonna come up with something. If it’s not EPO, then it’s ABC, XYZ, or MNO. I think if I pass all those tests, they’re still gonna say, ‘It’s something—the seaweed, the chemotherapy.’” The truth is, if Lance hadn’t so cavalierly dominated the Tour for the past two years, those allegations would never have been made. The French have been in a slump: A local hasn’t won since 1985, and their most popular rider is the drug-scandal-plagued Richard Virenque.

But the French also don’t like Lance’s attitude, especially about their language: He refuses to speak it. When Tour director Jean-Marie Leblanc suggested last year that he try as a way of breaking the ice with French media and fans, Lance, who seems to get a kick out of pushing their buttons, responded, “The Tour is a bike race, not a popularity contest.” He told me that last year when he did try, they took advantage of him, putting words into his mouth and asking hard questions. Perhaps what really rubs Frenchmen raw is that, unlike them, Lance didn’t grow up obsessed with the Tour de France, yet he owns it. This would be like little Pierre deciding, at fifteen, to learn to play basketball and then twelve years later schooling Michael Jordan in the NBA Finals. Again and again.

“Everyone Dopes Himself”

Cycling is brutal. To be great you need a killer instinct, like a boxer. You need to go one on one with another rider, a guy you know intimately, and after hours of riding your heart out, pounce on any weakness he shows and ruthlessly put him away. You need a certain meanness. “It’s a hard sport,” Lance told me. “It isn’t basketball, it’s not football, it’s not baseball. It’s five, six hours in the hills and mountains. And you know what? You gotta love it.

”Forty million French people watch the Tour de France on TV; ten million line the roads. It is cycling’s Kentucky Derby, and for an American team like US Postal, it’s the only race that matters. The Tour also happens to be the most beastly sporting event in the history of the world, at least when you’re talking about sports in which contestants are not intentionally killed—although riders have died since the race began, in 1903. Some two hundred riders form the “peloton,” or pack, that races about 2,300 miles over three weeks in July, with two days off. The race is, literally, a tour of France, with 20 or 21 stages of varying distances, though every year the route changes. There is plenty of status in winning a stage, but the real prize during the Tour is to wear the maillot jaune, or “yellow jersey,” which indicates the overall time leader. Riders power up 8,700-foot mountains and then roar down at 70 miles per hour, sometimes in rain and snow. They crash into cars, hurl their bikes in frustration, talk trash, and attack each other in anger. Their bodies undergo almost unimaginable strain; it’s no wonder they turn to chemicals for help. As five-time winner Jacques Anquetil famously said, “You can’t ride the Tour de France on mineral water.”

Few do. To even begin to understand the drug allegations against Lance, you have to grasp one undeniable truth: Doping is as important to professional cycling as the air in the tires. “Cycling,” says UT-Austin professor John Hoberman, who has written about sports and doping for more than a decade, “is the single most drug-drenched sport in history.” For the first fifty or sixty years, riders used strychnine, alcohol, cocaine, morphine, amphetamines, anything to give them—or that seemed to give them—an edge over the competition. “I dope myself,” Anquetil said in 1967, referring to his use of speed. “Everyone dopes himself. Those who claim they don’t are liars.”

Then came steroids and, in the eighties, human growth hormone and EPO, the superdrug. EPO is a reproduced version of a natural hormone that stimulates the production of red blood cells, the ones that deliver oxygen to the muscles and tissues. It is used to help dialysis, AIDS, and cancer patients like Lance, but since the late eighties—it was banned in 1990 by the International Olympic Committee (IOC)—EPO has also been supercharging the blood of endurance athletes, especially cyclists, helping them go longer, faster, and with less fatigue. Cyclists can train twice or even thrice as hard on EPO, stop taking it a week or two before the race, and still feel the positive effects, mostly in their ability to recover from daily one-hundred-mile rides. Says Mark Heintz, a former pro cyclist who returned to the peloton in 1999 to do a study on ethics and cycling: “You have a bottle of water and a plate of pasta and you’re ready to go again.” EPO, shot up like heroin, can boost an athlete’s oxygen supply 10 percent; it can help him go 3 miles per hour faster, which is like a basketball player adding four inches to his vertical leap—every player would want it.

And most riders wanted EPO. Jean-Michel Rouet and Phillippe Bouvet, cycling writer-editors for L’Equipe, a French sports daily, allege that a minimum of 90 percent of the professional peloton was using EPO between 1994 and 1998. Others, like former Festina team trainer Antoine Vayer, say it was more like 100 percent. Vayer says that in the mid-nineties, in hotel rooms at night, the Tour looked like a hospital, with all the injections and IV drips. It didn’t matter that EPO was eclipsing the skills and strategy of cycling. It worked. A handful of refuseniks opted out for religious or health reasons. EPO is not without its dangers—it thickens the blood and is thought to have caused some four dozen heart attacks and strokes in cyclists. It can literally stop your heart, especially at night, but that doesn’t stop riders who, according to Heintz, wear alarms that monitor their pulse as they sleep. Team managers regularly wake them in the middle of the night and walk them around to get their circulation going.

The risk, generally, is worth it. Cycling is big business and cyclists earn big money (Lance won about $335,000 for last year’s Tour), and if you don’t use EPO, you are almost certainly behind everybody else. “It’s not a game anybody wants to play,” a former pro rider told me, “but you have to if you really want to succeed. Each individual is responsible for his own decision.“ EPO abuse was, until recently, undetectable, and the only gauge to possible use was a person’s hematocrit level, the percentage of red blood cells in the blood. Usually that level is about 43 or 44 percent; if it went over 50, the cyclist was booted from the Tour. But the riders have always been a step ahead of the testers. Heintz wrote of cyclists hooking themselves up to IV drips containing a saline solution to dilute, in twenty minutes, the hematocrit level. He also wrote of riders injecting themselves in the testicles with masking agents to hide the presence of other drugs.

EPO abuse almost shut down the 1998 Tour de France, when Willy Voet, a Festina team trainer-masseur, was caught red-handed with 234 doses of it as well as other drugs. The Festina team was kicked out, and six other teams left in protest. Voet later talked about his involvement and wrote a book about the scandal, revealing a system in which the riders had no choice but to take EPO—only dopes didn’t use dope, and he alleged that between 60 and 90 percent of the riders did. He showed daily logs and schedules and told how doctors tinker with each rider’s chemical needs for that day’s ride. Riders even had their own centrifuges to monitor their hematocrit to keep it below 50 percent, he said. Nobody thought of it as cheating.

And Festina was not a rogue team. “It was not just Festina’s case,” says L’Equipe’s Rouet. “It was cycling’s case. Now you don’t have a rider who can say seriously, ‘I don’t take drugs in ‘96, ‘97, or ‘98.’” And, as former cycling pro Heintz found in 1999, it didn’t stop after the scandal (indeed, the Tour of Italy was temporarily shut down last month after two hundred police officers raided riders’ hotel rooms and confiscated large amounts of banned substances). Heintz wrote that “a systematic approach to doping is being carried out in world cycling,” with riders pooling portions of prize money to buy EPO on the black market. And it wasn’t just EPO but also human growth hormone, pure testosterone, and corticosteroids. Some refer to riders who dope as being “on the program.” Former Festina trainer Vayer says that during a Tour, some riders will take an average of thirteen substances, legal and illegal, with six or seven injections a day.

But they don’t talk about it. Dopers enjoy a solidarity that is maintained by a code of silence. “There’s a great conspiracy in the number of people concealing from the public the extent and influence of doping in sport,” says David Walsh, a sportswriter for the London Sunday Times whose weekly column often attacks doping and occasionally mentions Lance. Riders don’t see themselves as doing anything wrong; they’re doing what has been done for decades—making themselves better cyclists—so they deny doping. “The reason they’re such good liars is that their consciences are clean,” says UT’s Hoberman. “It’s a psychological phenomenon from being forced to lead double lives.”

Should they have to? If everybody dopes, what’s the big deal? Well, for one thing, everybody doesn’t do it. Doping isn’t fair. Also, it’s dangerous. And it turns cycling into a contest of one rider’s doctor versus another’s. Ultimately, doping is wrong. As French philosopher Roland Barthes wrote in an essay on the Tour de France, “to dope the racer is as criminal, as sacrilegious as trying to imitate God; it is stealing from God the privilege of the spark.”

Learning To Suffer

Lance loves winning, but the payoff is more than just being the first to cross the finish line. He wants to crush his enemies, real and imagined, like the dogs they are. In the spring of 1999, as he trained for the Tour de France, he did an interview with procycling magazine in which he talked about how various sponsors and teams had abandoned him when he tried to come back following his fight with cancer. “I remember what they did and I remember what the sport did,” he said. “And I just keep a list, a mental list. And if I ever get the opportunity, which I may or may not, I’m gonna pull out that list.” He soon got his chance, shocking everyone by winning the first stage of the 1999 Tour. Then, as he passed by members of the team sponsored by French credit company Cofidis—who dropped him in 1997, when he was recovering—he said, “That was for you.” By the end of the Tour and his smashing victory, he would find sweet vindication, rubbing the noses of all nonbelievers into the pavement. But many riders had not raced in the 1999 Tour in the wake of the Festina scandal, so they, as well as the media, questioned the legitimacy of Lance’s win, and he had something to drive him in 2000. It did.

“I’ve always been better when I’ve had things stacked against me,” Lance told me. This goes back to his childhood. He was born September 18, 1971, in Dallas and grew up mostly in Plano with a single mother, Linda Mooneyham. Lance refers to his father (last name Gunderson) as a non-factor. He called his stepfather, Terry Armstrong, “an angry testosterone geek” in his autobiography, It’s Not About the Bike. His mother would become his closest friend, staunchest ally, and inspiration, working her way up from selling fast food to selling real estate and supplying her son with such affirming truths as, “Make a negative a positive.” Lance took her advice, converting his resentments and insecurities into fuel (“I was a kid with about four chips on his shoulder,” he wrote). Eventually he was proving himself in long-distance running and swimming events. “If it was a suffer-fest, I was good at it,” he wrote, and soon he was doing triathlons and making money at it. By the time he was sixteen he was starting to concentrate on cycling, in which he was coolly defeating men in their twenties. When most kids were scraping for movie money, Lance was making $20,000 a year—paying for his car and food but still living with his mother.

He didn’t like Plano, which he has described as a “soul-deadened” place with no good cycling routes. After graduating from high school in 1989, he moved to Austin, a hilly city with great rides and more to do. Lance became hell on wheels. He was the U.S. National Amateur Champion in 1991, and he turned pro the next year, riding for Motorola and winning the 1993 World Championships. In his early years as a pro, Lance’s “Texan exuberance” (as one British commentator put it) rubbed a lot of Europeans the wrong way. He was young, brash, and reckless and didn’t know or care to know the history or traditions of the sport he was so blithely beginning to dominate: a handsome Ugly American. “I would bite somebody’s head off to win a race,” he wrote. He talked trash and brazenly pumped his fists at the finish, which was just not done. “He thought he was invincible,” his old cycling buddy John Korioth told me. The truth was, Lance was a scared and insecure kid who didn’t know any better, who feared more than anything being laughed at and not being liked by others. He didn’t know strategy and often suffered for it, riding too hard too soon and then losing energy and falling far behind.

His coaches, Jim Ochowicz and Chris Carmichael, would tell him to be patient. They knew Lance had the killer instinct. Carmichael once told him how cycling is personal, like a stabbing is personal, and Lance knew exactly what he was talking about. As long as the races were short, one-day affairs, he had a chance. Lance won a stage of the 1992 Tour de France, becoming the youngest ever to do so, but dropped out soon after, humiliated by the Alps. In 1996 he was the number one ranked cyclist in the world. He bought a Porsche and built a million-dollar home on Lake Austin, but he also spent a good part of the year in Europe. He was dating coeds and models. In September 1996 he signed a $2.5 million contract with Cofidis.

A few days after his twenty-fifth birthday party, Lance began coughing up blood in the sink. His right testicle swelled up like an orange. He went to the doctor, who had horrible news: Lance had advanced testicular cancer, which had spread to his lungs and brain. They gave him a less than 40 percent chance of living. His testicle was removed, lesions were taken off his brain, and he underwent four rounds of chemotherapy, during which his red blood cell count fell so low that he was given the miracle drug EPO. It was, he wrote, “the only thing keeping me alive.”

Lance survived, and cancer changed him in every way. He had always been an outcast, but now he found a community of others like him—scared almost to death but waking to a second life. Cancer dimmed his arrogance and gave him a new understanding of human frailty. It changed the way he dealt with pain. “I was shown a new level of misery and suffering,” Lance told me. “A hard training ride, bad weather conditions—stuff just doesn’t faze me anymore.” He changed his diet, and he lost weight. At 175 pounds Lance had always been too heavy to climb mountains well. Now, as he recovered and began riding again, he was a trim 158. He changed the way he pedaled and trained. His style became more mature and patient. “He always had this gift,” says Carmichael, “but after the cancer, he realized he couldn’t rely on it. To be a grand champion he was going to have to develop it.”

But he was damaged goods. Convinced he would never return to form, Cofidis terminated its contract with Lance in 1997. Other teams passed on him too. Only US Postal, a new team, made an offer, at a low salary. Lance accepted, but he would never forget those humiliating days. After a bout with self-doubt and semi-retirement, during which he lollygagged in Austin, playing golf and the stock market, Lance married Kristin Richard in 1998 (they would have a son, Luke, seventeen months later) and returned to racing. He won the 4-day Tour of Luxembourg, then placed fourth in both the Tour of Holland and the 23-day Tour of Spain. He had never done well in long races before. But that was then, this was now. And he was better.

J’ Accuse!

“I came back from the illness,” Lance told me, “and everybody said, ‘You’re not gonna do anything, you’re not gonna win anything, you’re not gonna finish anything.’ So I said, ‘Screw you. Why don’t I just focus on the biggest, baddest race there is?’ So I did.” In July 1999, 33 months after he was given a death sentence, Lance made history. He gave notice right away that he was not the same rider, winning the prologue and wearing the maillot jaune for the first time in his life. Ten days later, wired to Bruyneel, who gave orders and heart rates over the two-way radio, Lance was 2:20 ahead of his closest challenger when, on the eighteen miles of mountain leading up to the town of Sestrière, he made his most controversial climb. He was in a group of five, 32 seconds behind the two stage leaders and five miles from the top when he attacked, scooting around the others and taking off, a determined look on his face. “Armstrong is flying away,” said a TV announcer. He overtook all six and never looked back. One mile later he was 30 seconds ahead of the stage; by the time he hit the top, he was 6 minutes ahead of everyone. The Tour was, for all practical purposes, over. “That climb was so amazing,” L’Equipe writer Rouet says today. “It was so quick.”

Too quick for some journalists, including, at the time, Rouet. Walsh of the Sunday Times was in the pressroom when Lance made his climb. “There was a gasp of disbelief,” he told me, “audible skepticism. If it were valid, it was the most extraordinary thing we’d ever seen.” But he and the rest of the European press didn’t think it was valid. Festina was still heavy on their minds, as was the fact that the three previous Tour winners had all been shadowed by allegations, and now here was a walking dead man, an American, who was riding the fastest Tour in history. The next day the whispers became innuendo in the French press. “There is no evidence against him,” said Rouet at the time, “so he is innocent, but he is a strange case. . . . He is on another planet.” Reporters started asking questions, and Lance got into a heated exchange with some Le Monde writers, demanding, “Are you calling me a doper or a liar?”

Could the chemo have actually helped him? Perhaps the Americans had a new superdrug. “I can only assert my innocence,” Lance said. “I’ve never tested positive; I’ve never been caught with anything.” He passed all his drug tests except one, which found a corticosteroid in his urine. It turned out to have come from a cream for saddle sores. He was, however, failing the PR tests, coming on as hostile to the media, calling the accusations “vulture journalism.” He stopped talking to the press for a couple of days. He felt they were gunning for him, and of course, they were. Lance may be paranoid, but that doesn’t mean the French aren’t out to get him. Leery of sabotage, the team’s mechanic slept with Lance’s bike in his room.

Lance steamrolled into Paris to win the Tour in record time. Kristin and his mother were waiting. Back in the U.S., he was finally a star, hitting the talk shows that Tiger Woods appeared on. From near death to near myth: It was, many agreed, the greatest comeback in the history of sports.

It all happened again in 2000; this time the momentous climb took place on Hautacam, the Pyrenees mountain he had trained on so assiduously, and this time he was far behind the leaders when he rose from his saddle and attacked, pounding the pedals while other riders, exhausted from the day’s six-hour ride, labored up the side of the mountain. Again he blew by his rivals, including Marco Pantani and Jan Ullrich, two of the finest climbers in the world. Again fans along the side of the road pointed at Lance in disbelief as he sped past. Again it became obvious he was going to win the Tour. “Where he found the strength,” said an announcer, “I don’t know.” Again Lance donned the yellow jersey in front of a demoralized peloton. He had gone from six minutes down to four minutes up in eight and a half miles. Le Figaro headlined a story “Armstrong—Horseman of the Apocalypse.” And again came the doubters. The head of Mapei, one of cycling’s biggest teams, said, “Without doping, it’s impossible to be anywhere in the top five.” It was obvious who he was talking about. When Bruyneel heard this, he pulled out a photo of Lance training in the rain; he said it was taken on Hautacam two months before. And he said, “This is the secret of Armstrong.”

Lance, who passed all his drug tests, won by six minutes and was again, at least for a few days, the most popular American this side of Tiger. In France it was a different matter. Soon after the race, the France 3 video controversy erupted and the government began its investigation. “He’s a victim of a smear campaign,” Jeremy Whittle, the editor of Procycling magazine, told me in December, “because he never warmed to the French and they never warmed to him.” US Postal cooperated fully, claiming that the Actovegin was being used for abrasions and a staff member’s diabetes. Lance told me before he left for France, “At the end of the day, those guys are going to have to accept the results. We’re clean.” A few days later the court confirmed that the urine samples had tested negative; the blood samples are still being examined and the investigation is still open.

One clue to the longevity of the investigation is that Actovegin, which is extracted from calves’ blood, is not as innocent as its origin implies. Actovegin is used for everything from abrasions and ulcers to blood circulation problems. Though it is not banned, it affects the blood’s oxygen-carrying capabilities in ways similar to certain banned substances. Indeed, Festina trainer Voet had talked about using Actovegin to enhance the effect of EPO, taking EPO before the race and Actovegin during. “Actovegin is a blood product and is a type of blood doping,” says Prentice Steffen, the doctor for the American team Mercury- Viatel. “It works in conjunction with EPO, though it works just as well without EPO.” In December the IOC weighed in, saying Actovegin would, in fact, seem to be banned under current rules because of its oxygen-enhancing abilities. The IOC tried to ban it, but later changed its mind, saying more study was needed.

The whole situation would have been avoided if US Postal team members hadn’t driven their garbage sixty miles down the highway and, obviously, if the camera crew hadn’t been stalking them. Why, Lance was asked by Bicycling magazine, the secrecy? “Because as soon as we leave the hotel to drive to the race, journalists there look in our trash,” he answered. “And if they don’t look, then the maids look.” The investigation was truly exasperating, he told me. “It has caused me to question whether or not I love what I do, because it’s been a pretty exhausting winter. It has caused me to say, ‘This is crazy. How much of this can I put up with—do I want to put up with?’ The answer is: a lot.”

The Icon

“The thing about Armstrong,” says UT’s Hoberman, “is the mystery of his personality. Either he is being picked on because of his success or he is one hell of a brazen person. And the truth is, if he weren’t tough in certain ways, he wouldn’t be where he is.”

Professional athletes are different from you and me. In Lance’s book, he wrote how they cultivate the “aura of invincibility . . . neither are they especially kind, considerate, merciful, benign, lenient, or forgiving, to themselves or anyone around them.” Lance was especially so early in his career. He was, like many young athletes, arrogant with success, a casual ladies’ man (nicknamed by his teammates FedEx because of the slogan, “When you absolutely, positively have to have it—overnight”), a chest-thumping, angry testosterone geek. Lance, like other great athletes—Michael Jordan, Ted Williams—has a mean streak, a predatory nature that has to be channeled. “The guy can be a real hard-ass,” says old friend Korioth. “He can be real egotistical. But he has to be. He has to wake up every morning and go out, rain or shine, and pound it out. He has to believe he’s the best.” He is a blunt, intense person, a loner who will always have an outsider’s hardness. He is analytical, right-brained, and good with math—a high school graduate who is very smart. He suffers from allergies and, like everybody else in Austin, gets some small satisfaction in complaining about it. He loves chips and salsa, a major vice. He drinks Miller Lite. And he tries to live a life off the bike, away from the autograph seekers, photo sessions, and interviews. “It’s hard,” he told me, “to balance the whole thing of sport, fanfare, foundation, family, sponsors, and money.”

Lance may be private, but he is a public figure. As a courageous, gifted, and fair-skinned champion, he’s a Madison Avenue dream. It helps that, although Lance is no people person, he has a rock star’s charisma and a cheerleader’s smile. Last year Lance made $5 million in endorsements. This year he’ll make twice that from companies like Coke, Nike, and Bristol-Myers. As he has won, says his friend, lawyer, and agent, Bill Stapleton, the Lance Armstrong brand has evolved. “In the beginning we had this brand of brash Texan, interesting European sport, a phenomenon. Then you layered in cancer survivor, which broadened and deepened the brand. But even in 1998 there was very little corporate interest in Lance. And then he won the Tour de France in 1999 and the brand was complete. You layered in family man, hero, comeback of the century, all these things. And then everybody wanted him.” Nike was so enamored of Lance that the company signed him before it even had a cycling shoe, then made the famous TV ad that capitalized on all the drug rumors, showing him giving blood to suspicious doctors and riding his bike in the rain. “Everybody wants to know what I’m on,” Lance’s voice said. “I’m on my bike, busting my ass six hours a day. What are you on?” All the endorsements nicely supplement Lance’s US Postal salary, which just got bumped from $2 million to $8 million a year, making him the highest paid cyclist ever.

And then there are the speeches. “Lance charges twice what President Clinton charges,” says Stapleton. “Why is it worth $200,000? He sits on a stool, and he tells stories about himself. He tells the story of Hautacam—the reason he did so well was that in a training camp two months before that, he didn’t go up Hautacam once, he went up twice, because he didn’t think he had it, in the freezing cold rain. And so, what they take away from that is dedication, discipline, perseverance, commitment. That’s what people take away from a Lance speech, and that’s why he is, I think, the highest paid speaker in the country right now.”

The day after we talked, Lance spoke gratis to a crowd of 1,250 at the Austin Convention Center. It was the yearly Ride for the Roses gala, part of an entire weekend of cancer fundraising and races sponsored by the Lance Armstrong Foundation that would raise some $2 million, most of which goes to medical research grants. The gala was a smash: Avid cyclist Robin Williams gabbed and Shawn Colvin sang. At one point emcee Harry Smith, the CBS correspondent, said, “Lance does something to those of us who know him and those of us who admire him.” The room was packed with people who look on Lance as a savior, a guy who gives credibility to the idea that they are survivors and not victims, when often they feel the other way around. Three women received Carpe Diem awards for being, like Lance, living symbols of living with cancer. Perhaps the most compelling was Cara Dunne-Yates, a blind Paralympic medal winner in tandem bicycling with a mesmerizing message of hope, even as she prepared for another round of chemo. Lance followed her to say good-night and appeared genuinely moved: “Stories like this are what get me on the bike every day and get us out there.” Someone in the audience whooped and another shouted, “Tear it up, Lance!”

Does He or Doesn’t He?

It’s impossible to say. I talked with four people—two French, one American, one Irish; a doctor, a trainer, and two journalists—who say, unequivocally, yes. They have no proof—no needles, no photos, no witnesses, no positive drug tests—but think he’s the most visible of all the doped riders who are ruining cycling today. Their assumptions—Lance is only human, and humans just can’t ride like that. Everybody does it, therefore Lance does it—are based on what one of them calls “an intimate knowledge of the sport” as well as a sense of Lance himself as a guy who would do anything to win. I also talked with many more people—doctors, journalists, mostly Americans but also an Italian, an Englishmen, and a Spaniard—who say, unequivocally, no. They say he doesn’t need drugs and that he is saving cycling.

Lance has, of course, always denied using drugs. In his book he wrote, “Doping is an unfortunate fact of life in cycling . . . some teams and riders feel . . . they have to do it to stay competitive within the peloton. I never felt that way.” In truth, though, he has sometimes been evasive about the subject. In December, during the early days of the France 3 investigation, he wrote on his Web site, “Activ-o-something is new to me. Before this ordeal I had never heard of it, nor had my teammates.” Yet Actovegin was part of the doctor’s medical bag all through the Tour and an acknowledged use was riders’ skin abrasions. Could Lance really never have heard of it? “This doesn’t make sense,” I e-mailed him in early June when he was in Spain racing. “You’re a guy who knows everything that goes on around him.” He e-mailed back, “I cannot know everything that might be in our doctor’s medicine kit.”

He has also always downplayed the extent of doping in cycling. He told me, for example, that he found even Voet’s lower estimate, that 60 percent were doping, “hard to believe.” Nor has he been supportive of whistle-blowers like Christophe Bassons, a rider in the 1999 Tour who broke the riders’ code of silence when he repeatedly said that many were still doping after the Festina scandal. When he heard Bassons’ comments, Lance said, “What he’s said is not good for him or his team, his sponsor, and cycling. . . . he can’t speak like that, because sponsors will walk away from the sport.” Bassons soon quit the Tour, hounded out by fellow riders.

“I’m skeptical about all these guys,” says the Sunday Times’ Walsh, who this year won two Sportswriter of the Year awards in Britain. “But Lance is being held up by cycling as a symbol of the sport’s rejuvenation. Maybe he is the best, but you’ve got to wonder if he’s the best of the pack of doped riders.” Lance’s alleged doping is the subject, Walsh says, of a story he has been working on for a long time, as yet unpublished. He has no proof that Lance is a doper but, like many others, bases his theory on wisdom earned from many years covering the sport, including stories he has heard. Another Lance basher is a doctor—he requested anonymity—who works for an American team and who is certain Lance is doing all the major banned substances: “There’s no way he’s not ‘on the program.'” And your proof, I asked? “I have none. No video, no paper trail. It’s impossible to penetrate the system—the code of silence perpetuates itself.”

Pierre Ballester was a cycling writer for L’Equipe for twelve years who says he got so disillusioned with all the doping that he quit in February. “I’m fed up with all the liars, cheaters, and junkies,” he told me. And he had despaired especially about Lance (whom he liked and had interviewed several times, even visiting at his Austin home) and his superhuman performances, which he believed were drug-enhanced. “He’s not a machine,” says Ballester. “He’s not a mutant. I knew him, but I don’t know him anymore.” Ballester has no proof.

At the heart of the accusers’ argument is an oft-repeated mantra, “Nobody can win a big event in cycling without doping.” Ballester said it to me several times. Even Lance, I asked? “I leave the deductions to you,” he replied. That kind of thinking makes coach Chris Carmichael furious. “They had that same mentality back at Salem, Massachusetts,” he says, “and they burned a lot of innocent people. Lance doesn’t use banned substances or illegal drugs. He never has, and he never will.” Two of his former Motorola doctors, Pedro Celaya and Max Testa, also are angry about the allegations. “This is a lie,” says Celaya. “I’m working this job twenty years. I’ve never seen anybody like Lance. His mind, his body—it’s really incredible.” Whittle of procycling says, “I don’t think he’d be shocked at the thought of people using illegal substances. He knows it’s going on. But that doesn’t mean he’s doing it.” Lance’s friend Korioth remembers, “I never saw any record or indication of him wanting to do it. Beyond the health reasons for not doing it, Lance has to say, ‘What does something like that do to my reputation?’ US Postal would drop him. He’d lose his sponsorships. He has everything to lose and nothing to gain.”

Not surprisingly, Lance questions what his accusers have to gain. He saves his harshest words for Walsh—”I’d ask you to read his columns over time and see where he is coming from,” Lance e-mailed me. “You will see that, in my opinion, he plays it fast and loose with the facts and that he has reported things that are absolutely false”— and Ballester—L’Equipe “refused to bring him to the Tour,” he wrote, “because even they questioned his credibility on this issue.” (For the record, Rouet says there was never a problem with Ballester’s credibility.) Lance reiterated his mantra, “I’ve made the most unequivocal statements I can make about all the doping allegations. I’ve also been tested many, many times and my urine has now been tested from the 2000 Tour and it was clean. If that’s not evidence enough, I sincerely do not know what is.”

As Lance knows all too well, it’s impossible to prove a negative, and throughout the France 3 investigation he has claimed to be a clean rider. But did you, I asked him at the Hula Hut, ever do EPO back in the old days? “No,” he said. “I’ve admitted doing it, because I did it when I was sick. I think the raging years, the years it may have been a problem, were the years I was trading stock and sitting in Austin, hanging out at the Hula Hut.” But why, I asked, wouldn’t you use something that is, in your own words, “absolutely undetectable and unbelievably beneficial”? “It’s pretty scary,” he replied. “People have died from that. I’m not lining up for that job.”

“I’ll Be Hard to Beat”

For most of Lance’s life the odds have been stacked against him. Now, heading into the 2001 Tour, they’re 5-2 in his favor. “I guess Lance will win a third Tour de France,” says Ballester, “because he’s on top and he doesn’t have any big rivals. He’s better at mountains, flat stages, and time trials. Apart from an accident, no one will beat him.” Lance, as you might guess, is pretty confident himself. “I don’t know if I’ll win, but I’ll be hard to beat,” he said in April, on the verge of vetting the Alps again. “I’m two months ahead, right now, of where I was last year.” If he wins, he might even get some validation from new urine and blood EPO tests, though both detect drug use only within the previous three days (if Tour officials are to be believed, post-Festina testing and penalties have made a small dent in the abuse problem). Flawed or not, the new tests are a start, says L’Equipe’s Rouet: “You can’t have perfectly clean sports, but I think if Lance wins again with the tests, it will change the feelings of the fans and the press.” Except, of course, those who believe he and everyone else in the peloton have moved on to other, undetectable superdrugs.

Lance is on top of the world; what could possibly motivate him anymore? Well, there’s rubbing the Gallic nose into the pavement again, always a trusty pleasure. And beating his ex-teammate and former close friend Kevin Livingston, who is now racing for archrival Ullrich’s team. Lance would love to win a third Tour in a row, another step in a hinted-at goal of being the only man to ever win six. The truth is, Lance is one of those maniac champions who will always feel he has something to prove. Those who love him think he has shown enough heroism for one lifetime. Those who don’t say that will never be enough.

- More About:

- Sports

- Cycling

- Lance Armstrong