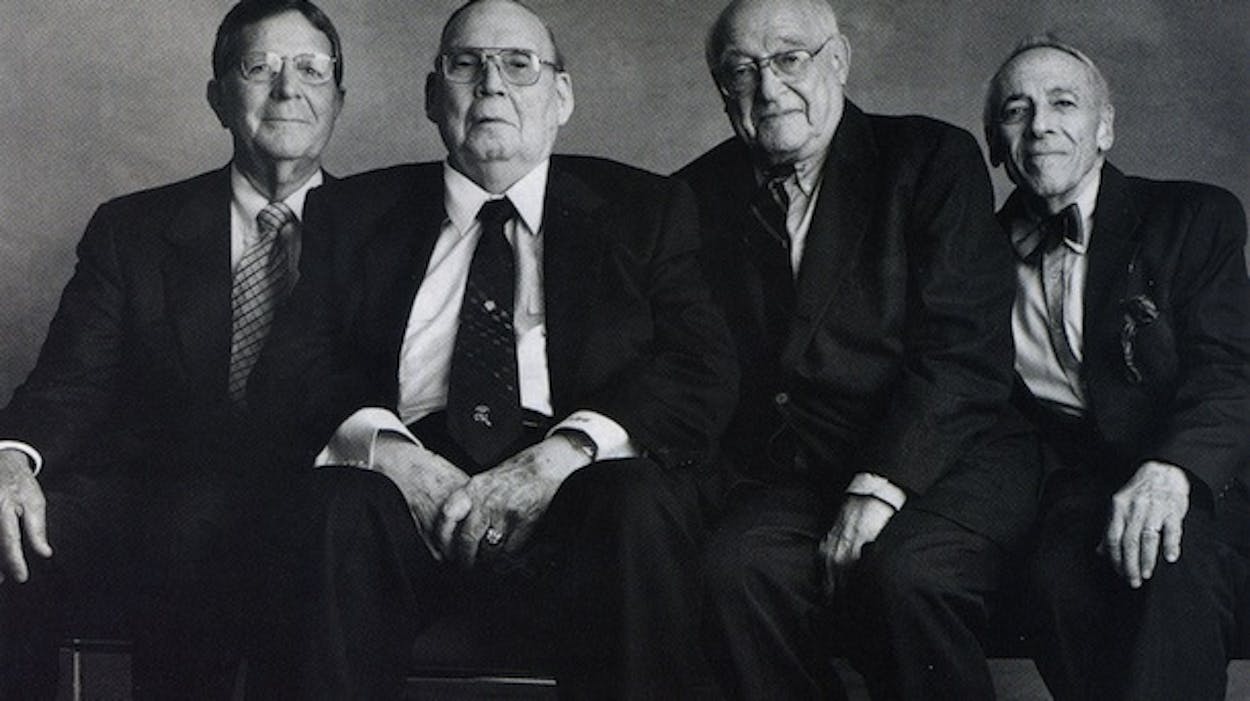

Robert Hardesty, Liz Carpenter, and George Christian were wearing their Sunday morning best on a Friday afternoon, waiting patiently for their picture to be taken. While the photographer coaxed them into position—telling Hardesty to move in a bit closer and Christian to turn slightly to the left—they talked about their favorite subject: politics. “You’re here with three political addicts,” Carpenter said, as the conversation between the former Lyndon Johnson aides veered into the day’s headlines: the execution of Gary Graham, the likely running mates of George W. Bush and Al Gore, and the latest twist in Hillary Rodham Clinton’s run for the Senate. Soon the topic turned to age. Christian, who is 73, said to Hardesty, four years his junior, “Bob, you don’t know how many times I have wished I was sixty-nine again.” “Yes, Bob,” the 79-year-old Carpenter counseled, “enjoy your youth while you still have it.” They had gathered to be photographed as part of a gallery, commissioned by Texas Monthly, that includes thirteen other advisers who were close to Johnson—from special assistant Jack Valenti to the head of the War on Poverty, Sargent Shriver. As the conversation that day revealed, time is a precious commodity for this dwindling group of survivors (“Everyone’s trying to get a speech out of me before I die,” Carpenter said later). Many of the principal players from the Johnson administration have already passed away. They include national security adviser McGeorge Bundy, Secretary of Defense Clark Clifford, Secretary of State Dean Rusk, press secretary George Reedy, and aide Walter Jenkins. Horace Busby, a longtime adviser, died a week and a half after the magazine contacted his office. In fact, it was 36 years ago this month that the Democratic party handed Johnson, then an incumbent president, its official nomination. Three months later he beat Barry Goldwater by winning the largest percentage of the popular vote in the twentieth century. The rest, of course, is history, or so we thought. Johnson passed the country’s most sweeping civil rights and anti-poverty programs while presiding over the greatest foreign policy debacle in American history. The war in Southeast Asia damaged his presidency so greatly that, less than four years after his triumphant election, he announced that he wouldn’t run again. Johnson’s place in history hinged on one word: Vietnam.

Twenty-seven years after his death, however, Lyndon Johnson has new life. Much of the resurgence has to do with Harry Middleton, the director of the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum, whose release of embargoed presidential tapes touched off a wave of revisionist history. Johnson’s image has been burnished by his old friends and colleagues as well. The surviving members of his administration believe that the country has only recently begun to recognize fully his leadership on civil rights, health care, education, the environment, and a number of other programs. “From most people, I used to get—even up until a year or two ago—a rueful appreciation of Johnson, saying how many great things he did for the country and that it was just too bad about Vietnam,” says Harry McPherson, a special assistant and counsel in the Johnson White House. “Now I don’t get the latter. I just hear, ‘Your boss was a great president who had vision.'” Joseph Califano, a top domestic affairs aide to LBJ, agrees: “Very bluntly put, the Vietnam War is over, but the Great Society programs go on. The issue between Bush and Gore is not whether to have Medicare or not, it’s how to save it. The whole dialogue has changed, and those programs are standing the test of time.”

Still, the greatest supporters Johnson has are his family, four generations of which also appear in this portfolio. Lady Bird’s place as one of the most respected women in Texas history is assured. She spent much of her time in the years following Johnson’s death watching over his business empire and the LBJ Foundation, which supports the LBJ Library and the LBJ School of Public Affairs. More recently, she has been devoting her time to the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, which she founded in 1982. “Her family comes first,” says 56-year-old Lynda Johnson Robb, “but the Wildflower Center is the center of her attention.” Lynda, who is Lady Bird’s eldest daughter, has been married for 33 years to Virginia senator Charles Robb, who is running a tight race for reelection this year. “My husband is a fiscal conservative, a social moderate, and he’s fighting for prescription-drug coverage for the elderly,” Robb says. “My father would approve.” Her eldest child, Lucinda, 31, is the director of recruiting for the Teaching Company, a company that sells educational materials. She lives in Arlington, Virginia, with Lynda’s youngest daughter, Jennifer, 22, a high school math teacher and field hockey coach. Catherine, 30, the middle child, is a lawyer in Austin. Lynda says that all of her girls love to travel, a passion that inspired Lucinda to backpack through Southeast Asia—including Vietnam—by herself. She loved the country so much that after she returned home, she persuaded her sisters to join her on another trip there.

Lady Bird’s youngest daughter, Luci, 53, returned to Austin from Toronto after the economic bust of the eighties to run the LBJ Holding Company, which her parents had been building since the forties. In 1993 she became the chairman of the board. Her husband, Ian Turpin, serves as its president. The company has interests in broadcasting, private equity investments, and real estate and has been particularly involved in the revitalization of downtown Austin. “All of us who lived through the eighties have an appreciation for diversity,” she says. She transformed the historic Brown Building, which once held the offices of her mother’s first radio station, into residential lofts. Her newest project is 220 West Seventh Street, a twelve-story $24 million luxury condo that will open in 2002. Her son, Lyndon, 33, is building his career as a lawyer in San Antonio, and her daughter Nicole, 30, is a full-time mother and volunteer (Luci’s daughters Rebekah, 26, and Claudia, 24, were unable to appear in the family photo; neither was her newest granddaughter, ten-month-old Eloise). Luci, like the rest of her family, is also a tireless community activist (Lynda once gave her a shirt that read “Stop Me From Volunteering”). Now that Luci has brought stability to the family business—which was estimated by Texas Monthly two years ago to be worth $150 million—would she ever run for office herself? “I learned a long time ago that if you ever say never, you will live to regret it,” she says. “I don’t envision it, and I’m not planning for it, but maybe someday I will serve in elected public office. I sure do want to serve my community, though.” No doubt her father would approve of that too.

Nicholas Katzenbach Age: 78

Attorney General, 1965-1966; Undersecretary of State, 1966-1969

Now: lawyer; Princeton, New Jersey

“I went to Martha’s Vineyard one weekend with my family, and I invited Bob McNamara and his wife to come with us. The phone rang, and the president said, ‘I think you had better come back to Washington.’ The Watts riots had broken out, but I told him I could handle the situation in Los Angeles from there. He got angry at me and hung up, and the phone rang a minute later. It was the White House operator wanting Bob McNamara. He [told Johnson], ‘I agree with what Nick had to say.’ The president said, ‘Well, I think you had both better come back to Washington.’ I later found out that Johnson was also trying to contact [speechwriter] Richard Goodwin, who was sailing off the coast of Martha’s Vineyard. Johnson later said, ‘I wish they’d just blow up that goddam island.'”

Robert S. McNamara Age: 84

Secretary of Defense, 1961-1968

Now: active in the non-proliferation movement and anti-poverty programs; Washington, D.C.

“I always believed that Johnson was an extraordinarily strong, effective political leader. I believed that before he became president and after he became president. Johnson kept Kennedy’s advisers—his Secretaries of State and Defense, his national security adviser—and the administration got deeper into the war in Vietnam. The question is, Would Kennedy have done the same? I can’t be certain. For one thing, South Vietnam’s president was killed in November 1963 and the government fractured. But I don’t think Kennedy would have gotten directly involved the way we did in the [war]. I think he would have recognized that even if the dominoes were likely to fall if we did not increase our military participation, we could not prevent it. There was simply no military solution to the problem.”

Larry Temple Age: 64

Special counsel to the president, 1967-1969

Now: lawyer; Austin

“One of my last conversations with Johnson was right before he died. I had a pair of shoes that were patent leather. The president told me, ‘Well, you rich lawyers have all those nice things. If I were rich, I’d like to have a pair of shoes like that.’ The next day, I sent him a pair with a note that said, ‘I know you can’t afford them’—he could have bought and sold me about a million times over—’but I want you to have these.’ He would wear them around the hospital and referred to them as ‘My Larry Temple shoes.'”

A. W. Moursund Age: 81

Longtime business partner

Now: lawyer, rancher, and businessman; Round Mountain

“The president needed a friend. I liked him, and he liked me. It’s just not true that we had a falling out before he died. But reporters were always telling lies about our business dealings. Smaller people think that tearing down someone builds them up. Back in the fifties, I was particularly mad at one story, and he just laughed and said, ‘A.W., don’t you know that if a chicken wants to get his head above the weeds, he’s going to get rocks thrown at him?’ I didn’t get much sympathy from him.”

Walt W. Rostow Age: 83

Chairman of the Policy Planning Council for the State Department, 1961-1966; national security adviser, 1966-1969

Now: professor emeritus, University of Texas; Austin

“People forget that Johnson was an important figure in foreign policy in the fifties. The last time he saw Eisenhower, they exchanged courtesies, and Eisenhower’s temples began to throb. He said, ‘If it weren’t for you and Sam Rayburn, I never could have conducted a civilized foreign policy.’ Whenever trouble would arise, Johnson knew all about the background to those problems.”

E. Ernest Goldstein Age: 81

Special assistant to the president, 1967-1969

Now: legal adviser to the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center; Austin

“I was in Paris practicing law, and I got a message that the president wanted to see me. I flew to the White House, and he asked, ‘Ernie, how soon can you go to work?’ And I said, ‘Well, Mr. President’—I was acting like a horse’s ass—’I’m doing some work for a Marlon Brando film, and I don’t know how long it will take.’ He put his arm around me and said, ‘I’ve got news for you. I’ve got bigger problems than Marlon Brando. You get over here in a week.'”

Joseph Califano Age: 69

White House aide in charge of domestic affairs, 1965-1969

Now: president and chairman of the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University; New York

“Johnson offered me my job from the shallow end of his pool. He shouted across the water, ‘Are you ready to come help your president?’ Another time, we were swimming, and we stopped near the deep end. He was poking me in the shoulder for emphasis as he talked. ‘I want to straighten out the transportation mess in this country,’ he said. ‘Next, I want to rebuild American cities. Third, I want a fair-housing bill.’ He asked me if I would help him do these things. Breathless from treading water, I told him I would. I didn’t find out until later that Johnson had brought me to a spot where he could stand but I had to tread water.”

Ramsey Clark Age: 72

Assistant attorney general, 1961-1965; deputy attorney general, 1965-1967; acting attorney general, 1966-1967; and attorney general, 1967-1969

Now: lawyer; New York

“It had never been a federal crime to assassinate the president—we had depended upon the states to prosecute those murders—so Congress decided to protect a number of federal officials, including the president. I testified for the legislation but opposed a provision for the death penalty on behalf of the Department of Justice. Johnson called me up after that in good humor and said, ‘Well, I see you were against the death penalty for the assassination of the president. What are you trying to do, get me killed?'”

Bobby Baker Age: 71

Secretary to the majority, U.S. Senate, 1955-1963

Now: real estate developer; St. Augustine, Florida

“After John Kennedy picked his brother Bobby to be attorney general, Johnson called me and said, ‘This will be the most humiliating thing that could ever happen to me if the Senate doesn’t confirm him.’ At his request, I contacted Senator Richard Russell, who was a great friend of mine, and I poured more whiskey in him than I should have. I said, ‘I know you have the votes to defeat Bobby’—because all the Republicans were going to vote against him and the other Southern Democrats would have voted with Russell. He agreed to go with Johnson, and that’s how Lyndon got Bobby confirmed.”

Liz Carpenter Age: 79

Executive assistant to Lyndon Johnson, 1961-1963; press secretary for Lady Bird Johnson, 1963-1969

Now: author and lecturer; Austin

“When Johnson left Parkland hospital on the day of the assassination, he saw me in a police car and motioned for me to follow him. We sped across Dallas to Air Force One, and once onboard, I became aware that there were no writers with us. I pulled out a card and scribbled some words—’…We have suffered a loss that cannot be weighed…’— for Johnson to use to make a statement. I’ve written thousands of words in my lifetime, but those fifty-eight were by far the most important.”

Robert Hardesty Age: 69

Speechwriter and assistant to the president, 1965-1972

Now: president emeritus, Southwest Texas State University; Austin

“I worked with Johnson on his memoirs after he left the White House. I had had a coronary and spent three months at home. We were eager to get back to work, so when I was getting ready to go out to the ranch, I realized that I hadn’t had a haircut. My kids told me, ‘Ah, Dad, that’s the style now.’ But the first thing LBJ asked me was, ‘Robert, your hair’s getting a little bit long, isn’t it?’ I told him it was to distinguish myself from those short-haired bastards in the White House, Haldeman and such. From then on his hair began to creep down to his shoulders.”

George Christian Age: 73

Press secretary, 1966-1969

Now: public affairs consultant; Austin

“We got into an argument about some matter, and I quit going over to his bedroom in the morning. LBJ asked why I wasn’t coming anymore, and when he found out I was mad at him, he arranged for me to go to Camp David with my family. Really, he exiled me to Camp David. So I spent some time there. I enjoy skeet shooting and had done that, but in the August heat with little to do, I called him and told him I was ready to come back. We made up, but do you know that when I returned, I got an itemized bill from the Navy for everything I had done, right down to every shell I had fired?”

Bill Moyers Age: 66

Special assistant to the president, 1963-1967; press secretary, 1965-1967

Now: broadcast journalist; New York

“The president called me just after the Daisy ad [which suggested that Goldwater couldn’t be trusted with nuclear arms] ran and said he’d been swamped with calls. He was having dinner with some people and was putting on this act, saying, ‘What in the hell do you mean running that ad? The Goldwater people are calling it a low blow.’ He told me to come over, and there were about eight or nine people with him when I arrived. I assured him that the ad was running only once and turned to leave. He followed me and whispered, with his back to the group, ‘Bill, you sure we ought to run it just once?'”

Sargent Shriver Age: 84

Director of the Peace Corps, 1961-1966; special assistant to the president for the War on Poverty, 1964-1968

Now: chairman and president of the Special Olympics; Washington, D.C.

“One Saturday morning he called me and said that he wanted to announce that I was the head of the new War on Poverty. I told him that I hadn’t talked to my wife or the people in my office. He said, ‘The truth is, we’ve just got to get on with the war against poverty. Talk to Eunice now, and I’ll call you back.’ So he called back about twenty minutes later and said in a low voice, ‘Now, listen, I’m going to announce you, and I can’t speak about it loud because I’ve got the whole Cabinet here, but you just have to understand that this is your president speaking.’ I turned to my wife and said, ‘It looks as if I’m going to be the head of the War on Poverty.'”

Harry Mcpherson Age: 70

Special assistant and counsel to the president, 1965-1969

Now: lawyer; Washington, D.C.

“I wrote both versions of the speech that Johnson was to give on March 31, 1968. I had done about a dozen drafts that proposed that the American people hang in there on Vietnam, but Clark Clifford made a passionate argument in which he said that the country wanted to change course. I wrote another speech that conveyed the desire for peace and sent them to the president with a note that said I hoped he selected the second one. He called me and started talking about changes he wanted in the second draft. That was all I needed to know; he was changing our Vietnam policy. I later told him that I had shortened the ending, and he told me that he might have a little ending of his own. The ending was that he wouldn’t run in 1968.”

- More About:

- Texas History

- Politics & Policy

- LBJ