If you climb the concrete stairs to the top of Mustang Stadium, one of the highest points in Andrews, Texas, and look in nearly any direction, past the parking lot and asphalt loop surrounding the town, mesquite-choked fields sprawl to the limits of sight. It’s not an unusual vista in West Texas. Neither are the innumerable pumpjacks that dot the desert’s horizon. Some stand still, giant silhouettes of metal. Others dip their bulky heads to the earth like horses bending to water. At dusk, you can make out the gas flares blazing yellow and orange alongside the pumpjacks and tanks, and as night blankets the prairie, the bright lights of drilling rigs shine against the dark.

This is the Permian Basin oilfield. And my home. The pumpjack is as natural a sighting to me as tumbleweeds and sand storms. I grew up in Andrews, a small town about forty miles northeast of the crook of the state border where New Mexico juts into Texas. The town felt small, and when I was a kid, people were more likely to leave than to move in. The few out-of-town visitors that did come wrinkled their noses at the sour stench of gas. But the smell rarely offended my nose. I grew accustomed to it, and when there was a particularly strong whiff of it on the wind, I’d mimic the elders and take an exaggerated sniff. “Smells like money.”

And I grew used to those oilfields. They were my personal playgrounds. In those fields my friends and I shot Coke bottles, dug elaborate trenches between the mesquites, and lobbed dirt clods at rattlesnakes and each other. We rode bikes for hours down dusty lease roads, and ate pre-packed sandwiches next to stock ponds or in the shade of a fiberglass oil tank. We learned how to drive our trucks through the mud after a rare heavy rain (and how to dig out a stuck pick-up when someone got cocky with their mudding skills). City kids had house parties; we had pumpjack parties. “Meet me after the game at The Bush Machine,” someone might say on a Friday night, and everyone knew which pumpjack that was. A buddy sprained his wrist “riding” the Bush Machine once, but most nights passed without incident. Just a few bored teenagers drinking beer stolen from ice chests left in the beds of oilfield trucks, listening to George Strait or Tom Petty, smoking Marlboro 27s, and talking about what we were going to do when we left this place.

Some of us did leave. I received a scholarship to attend Texas State University, and left brown, sandy Andrews on a warm August morning for the green hills and cool river of San Marcos. My sights had long been set on a career as a writer, so after I graduated I applied to a Master’s program in Ireland, about as far away from the Permian Basin one can get.

Nearly two years later, I had an MA in writing and several thousand dollars of debt. Even though Ireland had welcomed me like I was one of her own, it just wasn’t home. I missed the two-finger waves, the languid drawls of old-timers announcing Friday night games, the smell of chicken-fry and coffee in a diner full of ranchers and cowboys. I wanted vastness and emptiness and long stretches of lonely highway. I wanted stars and, most of all, I wanted honest-to-god Mexican food. I wanted West Texas.

Even across the Atlantic, it was clear that there was a serious boom underway back home. I was ready to leave the classroom behind for something grittier, something that would allow me to put my hands to use on anything other than a keyboard. Oilfield work seemed a perfect opportunity to spend some time with my family—who I hadn’t seen since I boarded the plane in Houston—while whittling down my student debt and learning a new trade. I sent an email to a childhood buddy, who had become a rig supervisor in Andrews. I told him I was moving back and would be looking for a job. He said he could find one for me.

I started working for him in January 2013. It was cold and the sky was colored charcoal with freezing rain. The rig supervisor took me seven miles north of town where one of their workover rigs (also called a pulling unit) was operating. At the time I knew nothing about oil production or rigs. The rig looked like a massive, hulking beast stubbornly planted in the desert, the top of the derrick standing one-hundred-and-four feet in the air like a grimy nail jutting toward the sky. The blocks, a chunk of metal weighing several thousand pounds used to lift and lower equipment, traveled swiftly from the rig floor to the crown of the derrick. Watching the metal move between the two floorhands and the tiny figure in the derrick, I felt a seed of panic sprout in my stomach. That was going to be me on the rig floor?

“Only if you’re up for it,” my buddy told me. I took another look at the rig. The operator revved the rig’s diesel engine, black smoke coughed from the exhaust pipes, and the blocks went skyward, pulling the string of oil-slicked metal pipe with it. “Yeah,” I told him. “I’ll do it.”

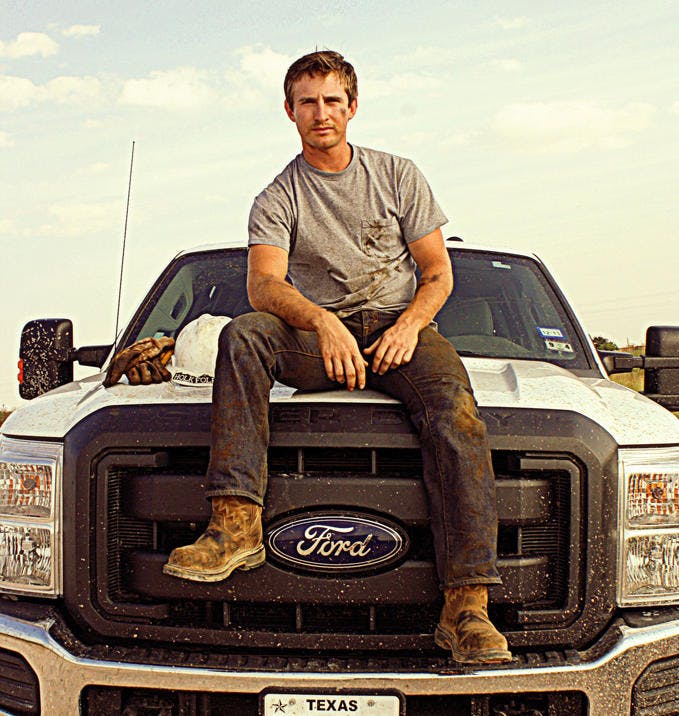

For the next year I worked as a roughneck. I jumped from rig to rig, filling in where a man was needed. If a floorhand was injured or sick, I took his place running the tongs. If the derrickman didn’t show or quit or was let go, I filled in on the floor while someone took his place. If all the rigs were running with four men, a full crew for a pulling-unit, I served as a hot-shotter, a glorified gopher, delivering parts and equipment to rigs anywhere along a two-hundred-mile stretch spanning from Sterling City, Texas, to Hagerman, New Mexico. Under the cover of hardhat and with coveralls and skin stained black with oil, my perspective of those flat plains with their endless flares and tank batteries and droning pumpjacks changed. My boyhood playground was now the office.

***

My mornings as a roughneck typically began at five a.m. The rumble of diesel engines all over town served as the crow’s call, the signal to wake up before the operator came to pick me up from my house. Once the entire crew was collected, the previous day’s rig ticket—which details the job performed the day before, the materials used, and the crew’s hours—is dropped off at the company yard and any parts or tools needed are collected from the tool pusher. The pusher oversees the rigs and is usually the main point of contact between the crew and the company man (the person subcontracting the rig).

The next stop is a local gas station: Stripes, Allsups, Valero, wherever has the cheapest diesel and shortest lines. A boomtown gas station in the early hours of the morning is a sight to behold. Roughnecks, roustabouts, pumpers, truck drivers, swampers, tool pushers, mudders, and company men descend upon these convenience stores for ice, coffee, and fuel for the trucks and the rigs. If you don’t have a wife or girlfriend packing you a lunch at home, you buy your lunch here: foil-wrapped burritos, fried chicken, steamed burgers. There are lines at every register, and every register is open. Like grannies at a small-town beauty parlor, the guys gossip about work, other crews, and each other’s families, using language a tad saltier than what you might hear at the salon.

Some men show up to the stations looking for work. “I just came in from Houston. Y’all need a hand?” someone might ask at the pump. It’s not uncommon to see a pusher pick one of these guys up. If a pusher is really in a bind, he’ll stalk a station looking to steal a whole crew. He’ll try to coax them into coming to work for him with promises of a nicer rig, newer tools, steady work, and most importantly better pay. Roughnecks are known to turncoat for a nickel more an hour.

The last of the morning ritual took place when we arrived on location, which almost always happened just as the sun was rising, no matter how far the rig was from town. The crew would shuffle into the doghouse, a small enclosed trailer, hauled from location to location by roughnecks. Here we would doff our street clothes, hang them in our lockers in the doghouse, slip into coveralls, and snatch a fresh pair of cotton gloves and our hard hats. The rig fired up. This was the last time we’d be clean for twelve hours.

***

A workover rig is, in the simplest terms, a smaller, mobile version of a drilling rig. Whereas a drilling rig’s objective is to “make hole” for a new well, a workover rig is used when an older well has gone offline and must be “worked over.” The pages of petroleum engineering textbooks are filled with reasons a well may quit producing, but more often than not the well must be “pulled,” meaning the tubing (metal pipe which functions as a sort of straw) and the rods (used to manually pump the fluid up through the tubing) must be pulled from the hole in order to fix the problem. Pulling a well takes up the majority of a workover rig’s time. The task isn’t particularly complex—most of the required motions becomes muscle memory after a short while—but every well seems to harbor one or two special quirks ensuring no one gets too bored or too comfortable.

One truth that transcends the differences between drilling rigs and pulling-units is that all new recruits are “worms.” A worm is easily spotted by his green hard hat and usually by his sluggishness compared to the other hands. Most worms like myself start on the rig floor. A floorhand is responsible for working the tongs, which is more or less a jumbo, hydraulic-powered wrench used to break connections on the rods and tubing. There are normally two floorhands working in tandem, and those two are usually the dirtiest on the crew—anything that comes up wet from downhole gets on these guys. The hand working high above the others on the tubing board is the derrickman. His primary task is to unclamp the rods and tubing, so the blocks can travel down for another haul. The added risk of falling to his death earns the derrickhand a little extra pay and is a sought-after position for young, cash-hungry worms. The operator is the captain of the ship. Not only does he control the rig’s every move, he’s responsible for corralling his crew, for constantly checking pressures and weight, and dealing with shit from the company men. Every time the rig groans to life, millions of dollars of equipment and the lives of three men are literally in his hands.

***

From what I understand, some things have changed since the heady booms of the eighties and decades before. More specifically, safety has become an issue. These days, everyone who steps foot on location is required to wear the proper “personal protective equipment,” or PPE. People who imagine men working in dirty tank tops or shirtless and splattered in crude are drawing from antiquated notions of what a roughneck looks like. Today everyone in the field is required to wear thick fire-retardant (FR) shirts and jeans or coveralls. (Ironically, the clothes that are supposed to protect a man from burning in a flash fire are made from materials that roast him in the Texas heat.)

The fashion may have changed, but the work is as filthy today as it was decades ago. Getting soaked with oil or blasted with mud is inevitable. There’s grease on everything, including us (there’s a reason we call the FR clothes “greasers”). Pipe dope, a thick, grey goop used to lubricate and seal threaded connections on pipes and flanges, gets everywhere. You are constantly sweating, no matter the temperature. Some companies provide laundry services, but many don’t. A regular washing machine will be ruined after a few loads, so once every couple weeks you find yourself at the laundromat looking for a washer designated “GREASERS ONLY.”

The OSHA-enforced dress code also requires steel-toed boots, a hard hat, protective eyewear, an H2S monitor (to detect toxic hydrogen sulfide gas, which smells like rotten eggs except in high concentrations when it kills the sense of smell), and gloves. If someone is missing any of these articles of PPE, the company’s safety man is going to chew him out (using some of that salty language I mentioned earlier). Enough write-ups and a man will lose his job.

When it comes to actual application of safety in the field, OSHA has a whole book on that, too, although no roughneck I know has read the damn thing. This is a job learned by doing, either by watching the men around you or by heeding their stream of swear-laced instruction. The first safety lesson I learned on the rig was profoundly simple: “Never stick your hand where you wouldn’t stick your dick.”

Safety protocols also dictate fashion, such as it is in these parts. By that I mean that mustaches are the only facial hair men are allowed to grow; beards and goatees prevent self-contained breathing apparatuses (SCBAs) from sealing to the wearer’s face. I’m convinced there is no higher concentration of mustaches in the world than the oilfields of West Texas. A baby-smooth face in the field is like a bull rider wearing a tiara—it’s just not right.

***

I grew a mustache, a grooming decision that earned me the nickname Cantinflas. The coloring of my facial hair—blonde in the middle, darker along the ends—reminded some of the guys of the Mexican comedian’s famously strange mustache. Other crews knew me as Sparky, the rig term for electrician, and quite a few of the Hispanic guys called me Gringo. Not original, but most monikers aren’t. One dude addressed me as Justin on the first day and though I corrected him, he never called me anything else.

Some crews spent months working together and didn’t know each other’s real names. In the field, knowing one another’s life story is not a priority. You’re given a nickname and that’s that. Some get named based on origin: Pampa from Pampa, Pecos from Pecos, Quirky from Albuquerque. A lot of guys are known by the female versions of their names: Antoinette, Stephanie, Roberta. At one point I was working with three “Lupes” at once. Certain names we used for one another I would not repeat in front of my mother. And, of course, no collection of nicknames would be complete without at least one based in irony. Shorty was a six-foot-eight colossus who worked as a spooler for Baker Hughes. He dipped Copenhagen, about half a can per pinch. Shorty lumbered around the rig floor like an adult trying to navigate a kiddie playground. He was, as the saying goes, a gentle giant. One time, during a particularly messy job, he stopped the rig for a hug break. Both of us covered in oil and dripping in decades-old drilling mud, he wrapped his arms around me in a smelly, sloppy embrace. No one—especially a fella who reminds his co-workers of a scrawny comedian with a funny mustache—refuses a hug from Shorty.

***

The penchant for nicknames reminded me of another organized institution that binds many roughnecks together: prison. It seemed like every other man I met had served time for DWI or aggravated assault or possession or robbery or something.

And prison teaches a man more than how to bestow a proper nickname. After a crew member once returned from a trip to Arizona, he told me, “Man, that hotel in El Paso was dirty, esé. Never going back. Not without my flip-flops.”

“You bring flip flops when you travel?” I asked him.

“Hell yeah, man.”

“That’s very hygienic of you,” I said.

“Oh yeah, esé, learned that in the can.”

I had never realized jail afforded such valuable personal sanitation lessons.

***

Guys rarely talked about serving time, but they would happily show off the tattoos they got while behind bars. Tattoos may be second only to mustaches in ubiquity amongst oilfield workers. I saw depictions of señoritas with single tears; artful renditions of eagles with bloodied talons carrying tattered flags; homages to former lovers or lost sons. And a lot of gang-related tats. Above the gut of a fat derrickman, two pistols aimed straight at whoever stood in front of him. “Brown Power” stretched across his chest in Old English font. A greying crew member mentioned he had covered up some ink linking him to a gang. I asked him why. “The Zetas said they’d cut it off me if I didn’t,” he said.

***

As tempting as it is to paint roughnecks with a broad brush, not all of them can recall an antagonistic encounter with law enforcement; many have records as clean as hospital sheets. I met honest, god-fearing men: a Baptist preacher, a number of team ropers, construction workers, police officers, school teachers, hard-working men who left their nine-to-fives for the pay. For good reason, too. A man in the fields can pull in between $50,000 and $75,000 a year these days—and some positions rake in even more. Pretty damn fine for a job that requires little previous experience and no degree.

But that money spends fast. Much like the cowboys of the Old West riding into town after weeks driving cattle with pockets full of freshly-made cash, a roughneck can net over $2,000 on pay day and return to the rig on Monday a broke man. Child support, court fees, truck payments, mortgages, and alcohol purchases suck a man’s pockets dry.

For some, the romantic notion of the job is more alluring than the cash. There is a certain amount of peace to be found in the relative isolation of a roughneck’s life. Miles away from town on location, a man can retreat into himself while performing long hours of steady manual labor with no one but the empty sky and mesquite to witness.

A floorhand I met left his law firm on the East Coast to find solace in the heat and hurt of the rigs after his life had crumbled at home. The lawyer had been on a pulling-unit for over a year when he lost a couple fingertips while tripping pipe. He’d never be able to play the guitar again, at least not like he could before. He returned to the rig after recovering, but something in his psyche shifted. Just wasn’t the same, they’d say. He eventually left the rigs to work in the yard, and quit a month or so later.

***

It is undeniable that life as a roughneck is dangerous. When I told my parents that I would be working as a floorhand on a pulling-unit, a notoriously treacherous job, my mom cried. Several family friends have been killed in the field. Injuries or deaths of workers are reported nightly on local channels. I promised my parents I would keep myself safe.

It may have sounded empty when I made it, but that promise saved my life. One scorching June day, our rig was swabbing a well. The process is simple enough, considered one of the most mundane tasks a workover rig can perform: ridged rubber cups are sent downhole to pull up sand or other unwanted junk out of the tubing so the well can flow more efficiently. I was the only fluent English-speaker on the crew at that time, which made me the point of contact with the company man. He had just called to get a progress report and gave the order to shut down for the day.

I climbed the steps to the rig floor to pass the word onto the operator. There was a popping noise. The sound of metal striking metal in the derrick. I thought the entire rig might be coming down. There was no time to look. I clambered over the side-rail and jumped about eight feet to the ground. I was running away from the rig as soon as my feet hit dirt. I reached the edge of location, forty yards away, before turning to see what had happened.

The operator was slumped over the brake handle on the catwalk. The other floorhand was laying on the rig floor, about three feet from where I had jumped. The sand line, a wire cable over half an inch thick meant to hold an extraordinary amount of weight, had snapped. Spinning violently back around the winch drum, the cable had unraveled into strands of flailing wire. The operator was struck in the back, his shirt ripped between his shoulder blades where two fine gashes appeared. The floorhand was hit in the leg. He had to pull some wire out of his calf.

By the time I drove the floorhand to the hospital, his boot was filled with blood. No one was seriously injured that day, but a buddy who works in safety told me it could have been much worse. “Normally when a sandline breaks, you don’t take a man to the hospital—you pick pieces of him out from around the drum.”

The next day there was tension in the doghouse. Any time a man is taken to the hospital, there’s a chance someone is going to get “run off.” The operator, a longtime veteran of the field, spit a thick stream of black chew out the open door then launched into an angry tirade, the majority of his wrath directed toward me. Most of it was in Spanish, which I don’t speak or understand well, so a good chunk of his barbed words went over my head. I did understand enough to know that he was calling me a coward, among other things.

“What was I supposed to do?” I asked. “You were on the brake. I thought the whole damn derrick was coming down.”

“Never leave the floor. Nunca,” he spit.

There was a part of me that did feel yellow, like I had done a disservice to the crew. But staring down at my ten fingers and wriggling all ten toes, I didn’t let myself feel too bad. “No, man, there was nothing you could have done,” my supervisor reassured me. “I’d have been hauling ass, too.”

***

The road can be just as dangerous as the rig. Once we were driving to location somewhere south of Artesia, New Mexico, and the only way to get there was a rural highway with no shoulder. I was in my own truck, so I could peel off from the caravan to deliver parts to another rig. The crew was following but never made it to location. Dispatch called—an 18-wheeler had hit their truck. The company truck was totaled. I took the crew to a hospital in Hobbs, but, on the order of the foreman, stopped at a clinic first to get each man tested for drugs.

These days, a rolled ankle could require a drug test. This is a far cry from the oilfield I grew up hearing about where rig hands regularly used cocaine or crank to keep themselves alert for days. Most guys today rely on energy drinks for a boost, guzzling several liters throughout the day. Not that this is much better than the drug alternative. Workers collapse regularly due to dehydration and other complications brought on by drinking too much of these caffeine cocktails. This wasn’t like drinking a few cups of coffee at a computer while powering through for a deadline; when we powered up with 5 Hour Energys or Monsters, it was a do-or-die attempt at willing our depleted muscles to keep moving in intense cold or oppressive heat. Because the work rarely stops.

***

Almost nothing halts operations on a rig—wind and ice among the exceptions. There were plenty of times a dust devil would blow in from a nearby cotton patch. Like a mini sand tornado, red dirt would come tearing across the caliche pad, leaving everyone in its path with grit in their eyes and teeth. While these were a nuisance, sustained high winds can cause real problems for the derrickman. Even though the substructure holding the derrick is rated to withstand gusts up to eighty miles per hour when the guide-lines are properly secured to the anchors (extra-long screws sunk into the four corners of the pad), a nasty West Texas wind can make even an experienced derrickhand squeamish. No foreman wants to lose time getting a well back online, but no good supervisor wants to risk the derrickman’s safety while handling pipe in strong winds, either.

As for ice, I spent several days watching my breath rise in the doghouse waiting for the rig to thaw. The puny flame from a propane tank did little to stymie the cold from working its way into every bone. On those days we sat mostly in silence. Each man journeying alone in his thoughts while smoke from a Marlboro Red curled between us. Outside, wind kicked ice from the derrick. Watching the white fluff fall, it could have almost passed as snow.

But the heat is far more common a problem. With temperatures reaching over 110 degrees on the caliche pad, you feel like an egg sizzling in a skillet. If bare skin touches anything metal, which is nearly everything around you, expect a welt to rise soon after. Picking up any tool or pipe without gloves becomes impossible by mid-day. Not even the biggest, toughest, baddest hombres in the field are impervious to dizziness, dehydration, and heat stroke.

***

Even in the best weather, problems with equipment or complications with a well can set a crew back hours, sometimes days. I might be home every night at six for a week, then one small misstep begets another and another until the pusher calls for a light tower and instructs us to work through Friday night. A derrickhand I worked with missed his son’s last high school football game when circumstances forced us to stay on a well until midnight. He never said a word about staying late. He just grit his teeth and climbed back up the derrick.

When the field is booming and the machine shops and supply stores are swamped with orders, it can take hours for a part to be delivered to location from town. Waiting around for a pump or special part is what we called a “hurry up and wait” situation. I always welcomed these breaks in the action as a chance to look for sun-bleached bones in the fields surrounding the rig or catch up on some reading. I wasn’t the only crew member with a predilection for reading, if the crumpled, mud-caked Playboy always lying around the doghouse was any indicator. But even during these down times, there is usually some work to be done: scrubbing tools with diesel, shoveling the pad clean of oil stains, or maintenance on the rig (there’s always some part that needs to be replaced or hobbled back together with bailing wire).

One of the few truly relaxing moments of oilfield work, at least to me, were the long drives from town to some far-flung corner of the field. While there are many who would claim West Texas is flat and ugly (and they wouldn’t be absolutely wrong), there is plenty of beauty when you know where to look. Over the Monahans sand dunes, I marveled at brilliant swatches of red, pink, and gold coloring the sky at dawn. I learned to search the horizon at sunset for speckled barn owls fluttering from their roost. Once when I was leading the rig down Highway 385 just as daylight started to spread over the prairie, a Vivaldi violin concerto came crackling over the FM radio. I rolled down the windows, turned up the stereo, and let the music float out over the mesquite. The rig behind me in the rearview, I had to laugh at the surreal poetry of the moment. In a place like this, you take it when you get it.

***

Long drives mean long hours on top of an already long work day. The workload may present difficulties for lovers or parents and their children. Fathers often come home too tired to play with their kids, and it’s commonplace to see men live out lyrics to country songs of promiscuous lonely wives. Then again, many crews in the oilfield are made up of families. I worked with a father and his son-in-law, as well as several sets of cousins. Sometimes an entire crew is comprised of family. This doesn’t mean those crews always get along. In fact, one foreman I know was summoned to location to stop a physical altercation between an all-family crew. When he arrived, the four men were brawling in the dirt.

Every rig crew is, in its own way, a weird little family. And our home is the doghouse. It is the locker-room, the water cooler, cafe, equipment room, office, smoke spot, and sanctuary of rig hands. It’s where we deliver a message or drop off tools. It’s here that roughnecks and operators catch their breath, stash their street clothes, huddle inside for warmth, or retreat for shade. It’s where company men and crew members gather for shared meals. It’s where a good cook, a treasured member of any crew, would set up his disca, a tractor-disc-turned-makeshift-wok, and sear fajita meat or fry picadillo.

Even though we spent many hours together in the doghouse, most of the guys in my crew didn’t know much about me—and I doubt they cared to, which was fine by me. When I left the oilfield the following January, I was realistic about my role out there. I was a tourist in a sense, just passing through. Not many people can hack the job for any prolonged period of time. It is a temporary means to an end, a payday loan one makes with his body. I’m proud to be able to say that I did it, that I was a roughneck—a member of that motley crew of rascals and ruffians. I carry a new appreciation for those fields of my youth and the men who work them. Covered in the guts of the earth, the rig roaring beneath me, I finally understood a truth that few know: Texas is rich with oil, but it’s the blood and sweat of the roughneck that keeps it pumping.