There’s no hall of fame for Texas writers, but to the extent that they’ve got a comparable brass ring to reach for, it’s the Texas Institute of Letters’ Lon Tinkle Award for Lifetime Achievement.

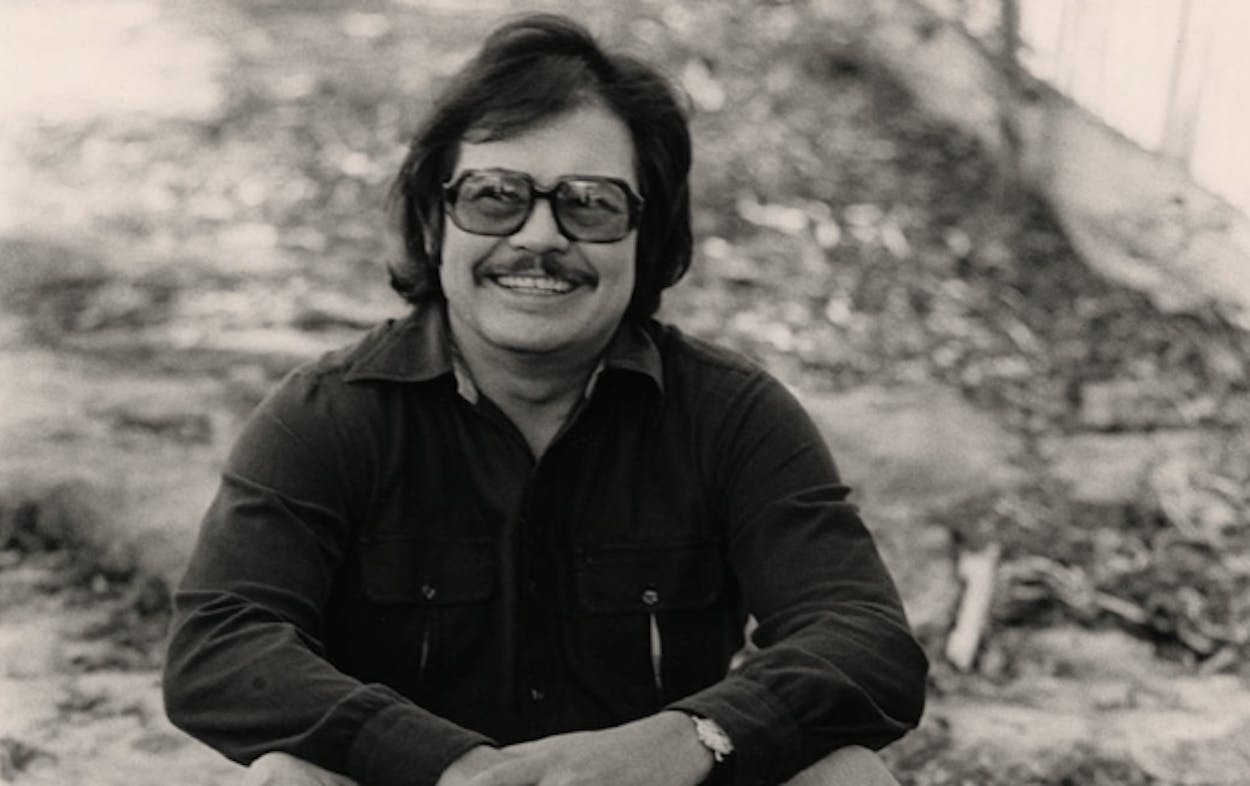

This past weekend in San Antonio, the TIL presented that honor to one of the writers who put Texas Monthly on the map, Gary Cartwright. It could be argued that the bestowal was overdue; Cartwright was 25 years into his career as a journalist-novelist-screenwriter and already a legend when the award was first given in 1981. And when he retired from the magazine in August, 2010, we fashioned our in-house send-off as “Our Tribute to the Best Damn Magazine Writer Who Ever Lived.”

But then the TIL, which was founded in 1936, has had a backlog of lions to recognize, names like Graves, McMurtry, Barthelme, McCarthy, Foote, Shrake, and King. Saturday night, Cartwright took his place among them in his typically humble, ribald, self-revealing style. Below is his acceptance address. Readers who have missed him from the pages of Texas Monthly will recognize his voice in an instant:

People ask me how I got to be a writer and I tell them I can’t remember. That’s not entirely true. The how part is a little foggy but I remember the why, and I believe the how and the why might be connected. In high school, I loved writing wild, disconnected passages in my notebook, pleasuring in the freedom of expression without the burden of too much thinking or the nasty exactitude of passing or failing grades. I did most of my writing in study hall, in the school library, enjoying the solitude and the musty smell of old volumes, secretly pleased at the sense of order and permanence they represented. Writing in my notebook was an effortless pursuit, and I thrilled as the words came flying off my pen like sweat off a wild pony.

I never dreamed anyone would actually read the gibberish in those notebooks, but to my great surprise the study hall teacher, Miss Emma Ousley, who also taught English and journalism at Arlington High School, not only read what I’d done but was impressed. She called me aside one day and said: “You know what, you have a talent for writing.” I was momentarily thunderstruck. Nobody had ever connected me to that word before—“talent”. Journalism and English, of course, became my favorite classes.

While I was still in college, I got a job covering the night police beat at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, working from six at night until two in the morning, then grabbing a few hours sleep before rushing to my eight o’clock at TCU. What a rush that was, the police beat–or cop shop as we called it–wearing a hat and trench coat like detectives in the movies and wading knee deep in rivers of crime, violence and sudden death. After a couple of years, I moved naturally into sports, first at the Fort Worth Press, then the Dallas Times Herald, then the Dallas Morning News, and for a blessedly short time, the Philadelphia Inquirer. Lot of stuff I never planned happened—newspaper gigs, magazines, books, screenplays, new friends who were writers or filmmakers or other literary types.

And so, many years later, I find myself standing here tonight accepting this glorious award–also known among some of my younger colleagues as the “I Thought That Old Fart Died Years Ago” citation—and at this moment I’m in mortal fear that I’m about to be exposed for the fraud that I know myself to be.

Writers hit walls almost daily, just part of the trade, but the hardest wall is the demand to explain what it is we do exactly. The How of it. So let me try again. Okay, say some thought or notion or wild dance of words pops into your head. If the moment makes you smile or in any way causes blood to rush to your brain, stop what you’re doing, take a shot of whisky, and write it down. Never mind that the odds of it being anything important are so staggeringly lopsided that only a crazy person would bother recording it. Having written it down, you will not be able to resist tinkering with the words, moving them about, standing them on their heads, turning them inside out until the combination seems satisfactory and maybe even pregnant with possibilities. At this point you will begin to wonder if it’s too early to make hotel and airline reservations to the National Book Awards. But first there is the problem of a second sentence. So you focus again on the task at hand and think of another batch of words. After a while, the process takes hold.

Over many years I’ve discovered that the process of writing is an agonizingly slower, far more painful adventure than jotting random thoughts into a school notebook. By that time, of course, I was addicted to the process–the work, the loneliness, the panic attacks, the super highs, the soul-searing lows, even the crushing failures which educate the writer to be intolerant of shortcuts. It’s the life I cut out for myself, and I was stuck with it. Small comfort in discovering that I was right all along–only a crazy person would attempt it. Anyway, it worked for me. Just like breathing in and breathing out, only with a red hot poker stuck up your ass. The trick, if there is one, is this: Don’t lose your nerve. Don’t let the bastards know that you’re not in control.

The turning point in my career was the fall of 1971 when I got a phone call from Billy Wittliff, telling me that I had won the Paisano Fellowship, a grant supervised by the University of Texas and the Texas Institute of Letters. Back then, Paisano fellows received a modest stipend of $500 a month and got to live and work for six months at J. Frank Dobie’s legendary Paisano Ranch, a magical 400-acre Hill Country spread on Barton Creek south of Austin. I was in Durango, Mexico, when I got Wittliff’s phone call, with my friend Bud Shrake, watching the filming of Bud’s original screenplay “Dime Box” and working on my own screenplay with Bud’s producer, Marvin Schwartz. Thanks in large part to Bud’s mentoring and encouragement, I’d had some successes. I’d written a number of pretty good magazine stories and published a novel and co-written with Bud a screenplay, only to watching helplessly as a certain dirt bag Hollywood actor snatched it away and tried to pass it off as his own work. In other words, I was learning the trade, that it was dirty and hard and without mercy–and while the process was in no way compulsory, it was an addiction very hard to resist. I’ve never been more in need of a break than I was the day I got that phone call from Wittliff. The Paisano fellowship was more than just a six-month sabbatical, it was permission to call myself a writer.

So, thank you, Billy Wittliff. Thank you, Bud Shrake, up there among the eternal stars in God’s good green heaven. Thank you, Texas Institute of Letters. Thank you, Texas Monthly. Thank you for believing what even now is suspect and may yet prove to be an illusion–that someone of such limited ability can come so far and be rewarded so handsomely.

In conclusion, I want to offer a piece of advice to beginning writers out there. The creative urge is like an itch in a place you’ll never reach. But that shouldn’t stop you from trying. If you improvise enough–rub against a cedar post, maybe, or get under a hot shower–it goes away, or at least stops itching for a while. But there is a reasonable alternative. If you can live with the uncertainties and awful fear of staring each day at stacks of blank pages, it ain’t a bad life, not bad at all. Success, I’ve observed, should be measured not in the number of pieces published or even their quality, but in the accumulation of days and weeks and years you’ve been able to pull off your scam. Therefore, my advice to all wanna-be writers is this: Forget About It.

But I know you won’t. In which case, I urge that you do your best and try to not take yourself too seriously.

Need more Gary Cartwright? Read his investigation of a handless private detective named J.J. Armes, his profile on the infamous Candy Barr, and a touching tribute to his wife Phyllis.

- More About:

- Gary Cartwright