This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

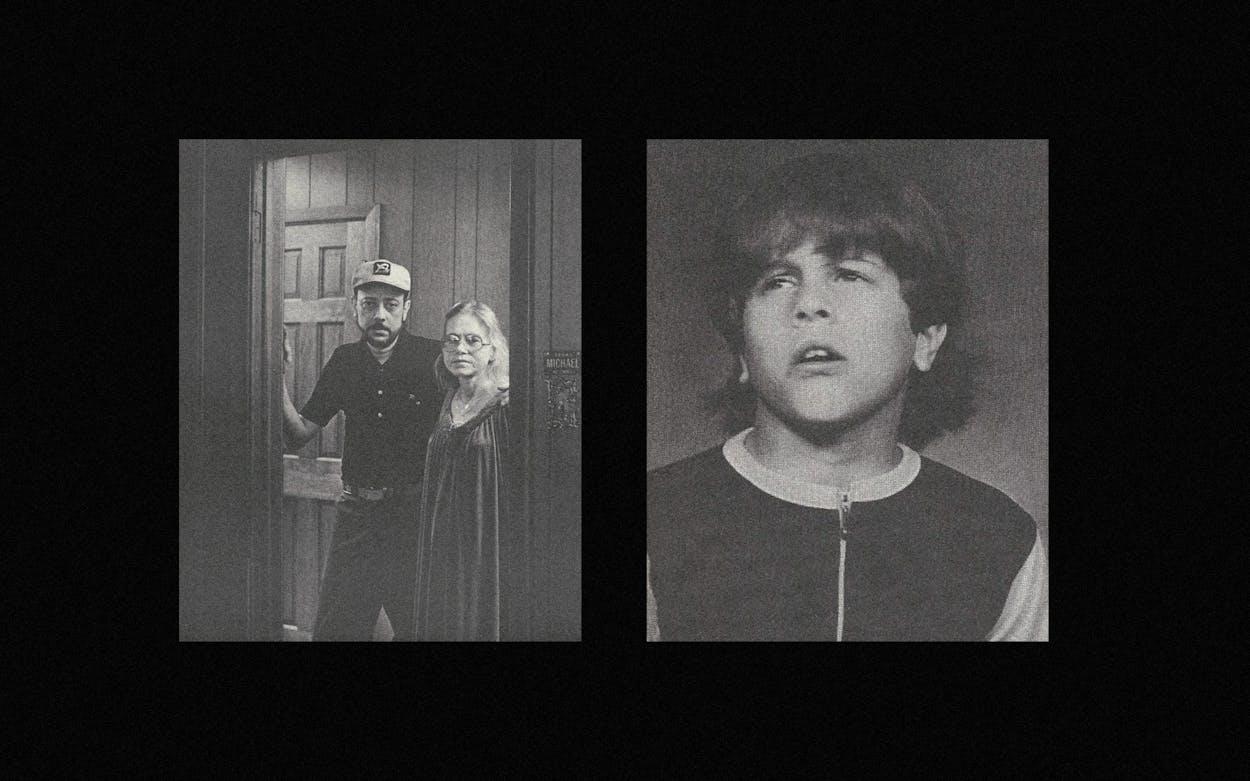

Forty-nine people died at the Austin State Hospital last year. Michael Shipley was one of them, but he should not have been. Michael, a slight, appealing autistic boy who had just turned sixteen, choked to death on his own vomit. He choked because his cough reflex had been weakened by huge doses of Thorazine, a tranquilizer he was given over his parents’ vehement protests. The doctors gave Michael more Thorazine than is considered safe for an adult, yet failed to insure that he was closely watched for the drug’s well-known side effects. Once the medical staff knew he was in danger, they did not monitor his condition closely enough. Even after the boy began to choke, he might have been saved by suctioning his lungs, but no one noticed in time. Minute by minute, the acid gastric juices in his vomit ate away Michael’s lung tissue. As his lungs grew less efficient, oxygen starvation set in and his heart began to work overtime in a vain attempt to compensate. Finally his heart failed and he died. The doctor who was present did try to reactivate Michael’s heart by manual massage, but the irreversible damage had been done.

Michael’s tragedy began long before his death. Part of that tragedy, of course, was autism itself: for any child to suffer the isolation, the fear, and the frustration of an autistic child is terribly sad. But the flaws in Texas’ mental health care system exacerbated rather than assuaged Michael’s tragedy. He did not belong in a state hospital—mental institutions are ill suited to treat people like Michael. He was sent there only because the state could offer no better alternative. This year we will spend more than $400 million to care for our retarded and our mentally ill. The Texas Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation (MHMR) operates an elaborate network of psychiatric hospitals, state schools for the retarded, human development centers, and community mental health clinics. And for what?

Six months after their son’s death, Sue and Robert Shipley wandered like ghosts through the ruins of their life. Their son had died a pitiful, senseless death; their health had crumbled; their life savings had been devoured by medical bills. Worst of all, they were tortured by macabre visions of Michael’s last days—of the agony and abandonment he must have suffered.

Unable to work, heavily sedated by his doctors, Robert Shipley padded in his slippers down the darkened halls of their home. Reminders of Michael met him everywhere: the unbreakable Lexan light fixtures, one still splotched with a bit of food Michael had thrown at it; the boy’s room, both windows boarded over to shield them from Michael’s attacks. Chain-smoking, worrying over his unkempt hair and beard, Shipley struggled through his son’s story. Every word cost him—the tranquilizers and the pain had hobbled his tongue—but slowly, agonizingly, the tale came out.

“When Michael was first sent to the state hospital, I thought, ‘This is the greatest—maybe they’ll find a cure for my boy,’ ” he murmured. “If only I had known, if only I had been told how it really was, I could have gotten him out. But I was just a few hours too late.”

In retrospect, Michael Shipley’s life resolves itself into a pathetic litany of If only . . . If only. . . . The first and biggest if only, of course, is if only he hadn’t been autistic. . . .

Getting Better

Michael was born June 28, 1963, into Houston’s Shipley doughnut family. Sue Shipley had had a hard pregnancy and a prolonged delivery, but the baby seemed healthy enough at birth. He proved sickly, though, and had to be hospitalized repeatedly during his first eighteen months. Michael’s father suspected very early that his son was “not quite right.” His fears were confirmed when Michael, then sixteen months old, began to rock incessantly and bang his head against his crib. The baby, who had not yet begun to talk, seemed happiest when left to sit in the dark. The Shipleys took Michael to their family doctor, who told them their child suffered from early infantile autism, a mysterious disorder often linked to mental retardation and marked by extreme withdrawal.

“Mental institutions are not the place for autistic people. They are sent there only because the state can offer no better alternative. We will spend over $400 million this year to care for our mentally handicapped. And for what?”

By his sixth birthday, Michael knew only a few words, and those he seldom used. He could walk and was toilet trained. Lights fascinated him: one minute he would take great pleasure in a light source; the next he would try to destroy it. He made a game of splattering lights with food or his own feces. Mechanical objects also intrigued him, and he could dismantle any household appliance without destroying it. He had an infallible visual memory; it was impossible to move anything in the house without his noticing.

As he got older, Michael’s obsessions grew less tolerable. Mealtimes upset him so badly that he regularly hurled his plate to the floor. People frightened him, and he often pushed them away sharply, occasionally inflicting bloody noses and other minor injuries. As he got bigger and stronger, his outbursts became increasingly hard to overlook.

Like many parents of autistic children, the Shipleys spent years switching from school to school and clinic to clinic, encountering only what Shipley calls “buck passing and quizzical attitudes.” For three years Michael went to classes at Houston’s Center for the Retarded. Then followed two years in the special education program of the Houston Independent School District. That ended when Michael suddenly refused to go to school. Rather than endure his tantrums, the Shipleys kept Michael, then eleven, at home for the next eighteen months. He had grown large enough to pose a real threat to himself and his surroundings, so they confined him to three rooms outfitted with special unbreakable lights. Shipley put paneling over the windows in Michael’s bedroom but still worried that the boy would injure his eyes by breaking a television set or window.

More and more, the Shipleys’ lives revolved around trying to reach their autistic son. They rarely left the house. They worked with him every day, trying to discipline his violent outbreaks by using techniques they found in books and newsletters, but Michael became simply too much for them. He was literally killing them: their health deteriorated until they were constantly in and out of hospitals for tests and surgery.

In September 1976 the Shipleys took Michael to the state school for the retarded in Richmond. After only two weeks they had to bring him home—he had refused to eat and had lost seven and a half pounds. At home they coaxed him into eating again and were soon able to return him to the school. But Michael was becoming increasingly hyperactive and self-abusive, and Richmond couldn’t cope with him. So in November the school referred him to the Children’s Psychiatric Unit (CPU) of the Austin State Hospital. The move saddened the Shipleys—their son would now be 150 miles from home rather than only 30. But they had no choice; they knew of no one else in Houston to turn to. And everyone assured them that the CPU would help Michael if any place could.

The Children’s Psychiatric Unit stands across the street from the state hospital grounds, both of them islands in the bustling center of Austin. As many as sixty children can live at the CPU, a small but modern and pleasant brick building flanked by its own day school. Michael arrived there anxious and impulsive, still dominated by lights. He had virtually no understanding of the world around him and no way to communicate his feelings and needs. The psychiatric evaluation conducted at the time describes Michael in stark terms: “Intellectual Functioning: severely retarded. . . . Judgment and Insight: nonexistent. . . . Diagnosis: nonpsychotic organic brain syndrome, mental retardation severe.”

For the next two and a half years the CPU staff would work to bring this sad child out of his isolated world. It was to be a long and bumpy road—at one time or another Michael bloodied the nose of just about everyone who worked with him. But they did make progress. In the beginning, John Douglas, Michael’s primary therapist, spent 32 hours a week coaxing his frightened charge to emerge from the unit’s back hallways. Gradually Michael’s self-abuse, which at the time consisted mainly of picking at insect bites, abated. Douglas believed that Michael struck out because he had no other way to communicate, so he concentrated on teaching the boy sign language. Michael picked up signs easily and even made up his own.

“Autistic children may not see or hear as normal people do; the complex barrage of sensations that our brains sort into everyday reality becomes a terrifying jumble.”

“He got really excited about being able to communicate,” Douglas recalls. “He was a real joy to work with because all his emotions were right on the surface. Most children are much harder to read. He was one of a kind.”

Douglas worked with Michael’s teacher, Jo Webber, to increase the boy’s self-control. Slowly, they won small victories. Michael continued to hit strangers who came too close, but he learned to sit on his hands or ask his friends to hold them so he could not lash out. Douglas would sit beside Michael as he ate, always ready to restrain him if he tried to shove his tray off the table, structuring the situation to make Michael feel secure. The strategy worked. Michael gained weight steadily until he weighed over a hundred pounds. During most of his tenure at the CPU, Michael was also receiving moderate doses of psychotropic drugs—first Thorazine and then, when he reacted poorly to that, Navane. No matter how much progress he made, though, Michael’s bizarre fixation with lights persisted. It worried his therapist more than any other symptom, because it meant that he was too unpredictable to be discharged from the unit.

Decline and Death

Hospital regulations decreed that Michael could remain at the CPU only until his sixteenth birthday, June 28, 1979. He then had to transfer to the Adolescent Unit (AU). The two units are across the street from one another, but they might as well have stood a continent apart. While nominally they functioned as two components of a single treatment system, in reality they scarcely communicated with each other. Each had a strong-willed director and a treatment philosophy all its own. The children’s unit had 40 per cent more direct-care workers per patient, better facilities, and a more prestigious reputation, none of which endeared it to the AU. Left by the hospital administration to chart their own courses, the two units quietly but determinedly went their separate ways.

The Shipleys knew none of this at the time, but still they worried over the impending transfer. All autistic children resist change, so his parents knew the move would upset Michael badly. But hospital rules said he must go, so preparations for the transfer began that spring. The Shipleys repeatedly sought assurances that Douglas and other CPU staff members would be able to visit Michael at the Adolescent Unit to ease his transition. They interpreted the AU staff’s vague rejoinders as assent. In fact, nothing could have been further from the truth.

From its inception, the children’s unit had been a sore spot with Dr. George Tipton, director of the AU, the man who would most profoundly affect Michael’s life in his new home. Perhaps Tipton resented the children’s unit because it was better funded and better staffed; in any case, his animosity was no secret at either unit. And even more than he disliked the CPU in general, Tipton disliked John Douglas. According to the official report on Michael’s death, an intern being trained by Douglas had seen an AU worker verbally abuse a patient several months before Michael’s transfer. The intern told Douglas, who mentioned it to a hospital administrator. Tipton felt his authority had been usurped and closed his unit to Douglas and all the interns working with him.

Although Michael’s transfer was scheduled for July 2, in mid-June he suddenly began striking a three-year-old child who had just been admitted to the CPU. Arrangements for the move were only partially complete, but the staff decided that Michael’s attacks on the younger child were serious enough to warrant moving him immediately. Late on the afternoon of June 18—two weeks ahead of schedule—Michael’s CPU caseworker called the Shipleys to say that Michael had been transferred to the adolescent ward. John Douglas was vacationing and did not learn of the move for two weeks.

On June 21, Michael’s mother traveled to Austin to see him. He had been put in an isolation room soon after the transfer because he was so upset, but he seemed happy to see her. She treated him to cookies and candy, sat with him for a time, and left. When she returned that afternoon and again the following morning, she was informed that it would be best for Michael not to see her, since he would only act up when she left. From that day until his death, the Shipleys were to have only one telephone conversation with their son. Whenever they called to talk to him they were told that he was resting. They were also told, they say, that he was doing just fine.

The record shows, however, that from the day after he arrived at the Adolescent Unit Michael received increasingly massive doses of Thorazine, a powerful tranquilizer. The staff of the children’s unit had found that Michael responded better to Navane than to Thorazine and that his aggressiveness seemed to increase with anything above a modest dose. But Tipton immediately ordered 1000 milligrams of Thorazine a day—two and a half times more than Michael had ever received at the CPU. When that failed to make him tractable, Tipton increased the dosage, first to 1400 milligrams and then to 1600. On several days Michael was also given supplementary 50-milligram doses when he became unmanageable. John Douglas did visit Michael one time early in July. He found the boy again in an isolation room, frightened and disoriented. Food lay on the floor where Michael had thrown it, and he looked to Douglas as if he had lost a lot of weight, perhaps twenty pounds.

Around July 16, Michael began to bang his head against the wall. The next day Tipton upped the Thorazine to 2000 milligrams. In discussing adult dosages, the Physician’s Desk Reference states: “500 mgs. a day is generally sufficient. While gradual increases to 2000 mgs. a day or more may be necessary, there is usually little therapeutic value to be achieved by exceeding 1000 mgs. a day. . . .” For a week Michael banged his head, until his face was covered with bruises and cuts, his eyes swollen shut, and his head “beaten to a pulp,” according to one staff member. His medical record does not indicate what—except ordering supplemental doses of Thorazine—was done to prevent his self-destruction. On Wednesday, July 25, Dr. Robert Sanders, acting in Tipton’s absence, increased the dosage of Thorazine to 2400 milligrams, had Michael put in a football helmet and protective mittens, and directed the nurses to check Michael’s vital signs twice a day. His vital signs were checked, but only once a day. When Tipton returned on July 27, he approved Sanders’s orders.

On July 26, Michael’s social worker had called the Shipleys to tell them that their son had hurt himself and been put in protective headgear. His eyes were a little blackened, the worker said, and his face a little puffy. The Shipleys said they would hurry to Austin the next day. Soon, however, the caseworker called back to say that since the doctors planned to x-ray Michael, it would be better not to excite him by suddenly appearing. Shipley had been arguing periodically with the caseworker that Michael should not receive Thorazine; now he pleaded with him to change medications and to have John Douglas visit Michael. Douglas was not called.

X-rays taken Friday morning showed that Michael had not done himself permanent damage. The caseworker called to reassure the Shipleys, and he and Shipley argued again over Michael’s medication and whether John Douglas should be consulted. The caseworker persuaded the Shipleys that they should delay their visit until the following week. Over the weekend Michael seemed quieter. On Sunday night a nurse mentioned to Shipley in a telephone conversation that she had bathed Michael’s swollen eyes and he was once again able to see. Aghast at the revelation that his son had ever not been able to see, Shipley determined to visit the unit unannounced the next day.

Early Monday morning a nurse found Michael wheezing, bluish, and drooling vomit. He was lying in his own excrement, which was also all over his hands. Fearful that he had swallowed feces, thrown up, and then inhaled vomit, the nurse tried to suction material out of his lungs, but with little success. She called the doctor on duty and was told to transfer Michael to the Medical/Surgical Unit for chest x-rays. A doctor viewed the x-rays at 6:30 a.m. and agreed with the nurse’s earlier diagnosis. The record does not indicate whether Michael was observed during the next three and a half hours. At ten o’clock the director of the unit found Michael sitting up, yelling, and striking out. However, he had apparently vomited again and inhaled his vomit while unattended. When the director returned at eleven he was quiet, seemingly asleep. Then, as the director listened through a stethoscope, Michael took five or six quick breaths and his heart and breathing stopped. The doctor tried to revive the boy with mouth-to-mouth respiration and manual heart massage, and ordered a shot of adrenalin, but to no avail. Just before noon, as Shipley prepared to leave for Austin, his phone rang. When he answered it, he was informed that his son was dead.

What’s Autism?

Autism is a hot topic in research circles these days; still, the nature and causes of the disorder elude discovery. Even the definition of autism—which symptoms are essential to the syndrome and which are secondary—is not clear. Most doctors agree on four characteristics of true autism: children are stricken within the first three years of life, they do not develop normal language, their social relationships are stunted, and they violently resist change. Autistic infants do not like to be picked up and cuddled, and they do not respond to their parents or even seem to notice them. Some autistic babies scream all the time; others demand next to nothing, not even crying to be fed. An autistic child does not respond when spoken to. He prefers to be alone and can amuse himself for hours by spinning a coin or a plate, twirling a string, or simply rocking back and forth. Although he seems totally oblivious to his environment, he becomes passionately attached to certain objects and routines and may throw a screaming fit if a piece of household furniture is moved, or if one pebble out of a boxful is missing.

Four or 5 of every 10,000 children are born autistic—making autism about as common as congenital deafness and more common than congenital blindness. By this reckoning, approximately 100 autistic children will be born in Texas this year. Four times more boys than girls are autistic, which suggests some sex-related genetic component in the disorder, but so far this hypothesis remains unconfirmed.

Many autistic children, even those who have little or no speech, possess other highly developed abilities. A child who appears severely retarded in every other way may be able to multiply four- or five-digit numbers in his head almost instantaneously. Others teach themselves to play advanced instrumental music or even compose their own pieces while still very young. These inexplicable flashes of brilliance, sometimes called splinter skills, both encourage and frustrate parents by holding out the hope that somewhere deep within this troublesome, enigmatic little stranger lurks a bright, affectionate, normal boy or girl. Intriguingly, if a child’s autistic behaviors are eradicated, his splinter skills disappear as well.

Diagnosing autism is immensely complicated, because many other disorders—deafness, mental retardation, schizophrenia—produce behaviors that look markedly autistic. And most autistics are at least mildly retarded. Too, children whose autism goes untreated for more than a few years often develop severe emotional problems as a consequence. Those who end up in mental institutions—as the majority do—eventually degenerate until they behave like chronic schizophrenics.

In 1943, when Professor Leo Kanner first identified the group of symptoms he christened early infantile autism, he focused on his observation that autistic children seemed isolated within themselves—hence the term “autism,” from the Greek word autos, “self.” Kanner saw autism as an affective disorder, one rooted in the emotional processes. This theory led him to examine the emotional environment of the autistic children he encountered and to conclude that virtually all of them had parents who were exceptionally intelligent but cold, mechanical, and unloving. Although Kanner later retracted this view—which was based on casual observation rather than controlled experiments—it was popularized by psychologist Bruno Bettelheim. Today both parents and professionals accuse Bettelheim of having caused untold needless suffering for parents of autistic children.

Once scientific studies had disproved the “refrigerator parent” theory of autism, researchers began to concentrate on possible biochemical and neurological causes of the syndrome. Because autistic children often act as though they were blind or deaf or both, many investigators attribute autism to a sensory malfunction. They believe that autistic children do not hear or see as normal people do, that either the sensory organs or the parts of the brain responsible for processing sensory information do not work properly. If this is the case, the complex barrage of sensations that our brains miraculously sort into everyday reality must be a terrifying jumble to the autistic child. In order to escape the fright and frustration caused by this avalanche of senseless stimuli, the child learns to shut out the world in ways that seem bizarre to us. For example, one autistic child suddenly passed out for no apparent reason. He was rushed to a hospital, where the doctors found that his appendix had burst, causing peritonitis. But the child had never so much as whimpered—he seemed to feel no pain at all.

As a consequence of such blocking, the autistic child risks severe sensory deprivation, which can cause disorientation, hallucinations, and even death. Just as inexorably as it requires food, the human body requires sensory input—without it the central nervous system goes berserk or perishes. So the autistic child develops highly specific, repetitive, somehow tolerable means of self-stimulation, or “stims.” These stims, which tend to be remarkably similar from child to child, include most of the behaviors that make the autistic child look so strange: rocking, spinning, hand-flapping, head-banging.

The autistic child also has severe problems with language. Very few autistics begin to talk at a normal age, and those who do often stop talking later. Many can accurately mimic phrases they have heard but must struggle for years to learn simple words to communicate their own wants and needs. They may learn to “read” at a very early age, memorizing the sounds that go with the printed words but not comprehending what they are reading at all. Even those who do learn to talk can seldom converse naturally; their conversation sounds stilted and mechanical.

To say that autism stems from a hitch in the sensory and language processes does little to explain its basic mechanism. A staggering number of complex steps are involved in each of these processes, and researchers have barely begun to sort through the hundreds of chemical reactions and millions of interconnecting nerve cells that might be at fault. Do certain viruses trigger autism? Is it a product of undetected food allergies? Is it caused by a vitamin deficiency? Perhaps an error in the series of chemical reactions in the nervous system? Or an injury to some part of the brain? Evidence exists to support each hypothesis, but so far none is compelling and certainly none promises a cure.

The confusion over autism’s characteristics—let alone its causes—means that most parents of autistic children spend months or years being shunted from one specialist to the next, getting only inconclusive or contradictory diagnoses and a string of referrals. By the time they have either found a workable school program for their child or given up and put him in an institution, they, like the Shipleys, have become wary, battle-scarred veterans of the social service system.

What Went Wrong?

His son was dead. As the news sank in, Shipley’s mind began to seethe with anger and confusion. How could this have happened when Michael was supposedly doing so well? The longer he thought about it, the madder he got—he had been outwitted and it had cost Michael his life. But the anguished father didn’t know what to do, so he contacted Michael Twombly, executive director of the Texas Society for Autistic Citizens (TSAC), an Austin-based advocacy group that has its finger in every conceivable political and educational pie. Twombly began asking questions of MHMR. He also called in Mack Kidd, one of the state’s best personal-injury lawyers, and Dayle Bebee, director of Advocacy, Inc., a federally funded legal service that protects the rights of the handicapped. The Austin State Hospital pathologist had concluded that Michael died of “natural causes”—either a heart defect or choking on his own vomit or both. But in September the Austin American-Statesman published an article citing preliminary evidence that the boy had been neglected or abused at the Adolescent Unit. The story also quoted the Shipleys and John Douglas at length.

Shock waves began to reverberate through MHMR. The AU staff reacted with bitterness and summoned John Douglas to explain why he had spoken to reporters. In late September the MHMR board created a task force to study the needs of autistic Texans. The department’s investigative team completed its report on Michael’s death in October, but MHMR withheld it from the Shipleys because the information in it might be grounds for a lawsuit. The report was leaked to the American-Statesman in mid-December; days later the Shipleys filed suit to force the department to release it.

The report denies that Michael lost twenty pounds or more in his seven weeks at the AU (contrary to standard procedure, no body weight was recorded at the autopsy). It also concludes that he was not attacked by other patients on the unit, who the report says were afraid of his unpredictable behavior. Other questions it skirts entirely, particularly whether or not the Shipleys were misled about Michael’s condition even after his head-banging began. But it relates in great detail the events immediately preceding Michael’s death, from the escalating doses of Thorazine to the lack of nursing care. “In summary, there does seem to have been an inadequacy of documentation in regard to Michael’s treatment after he was transferred to the Medical/Surgical Unit,” the report laconically concludes.

Once the report was written, the attorney general’s office began negotiating with Mack Kidd for a settlement. Tipton, who had announced his resignation weeks before Michael died, left the Adolescent Unit in a shambles. The AU limped along with only one psychiatrist (Sanders) and no permanent director. AU staff members worried that the hospital was laying itself open to charges of negligence. For over six months hospital superintendent Luis Laosa vacillated about the choice of Tipton’s successor. In January, Sanders resigned. The following week Laosa appointed a new director.

Michael’s death notwithstanding, the Adolescent Unit is not Bedlam. The visitor encounters no overt cruelty there, no squalor, no filth. The rooms look reasonably clean—as clean, say, as a typical college dorm. The cinder-block walls are painted in pastel colors and glossy white, enlivened by bright murals depicting fantasy landscapes. The professional staff and the teachers supplied by the Austin schools appear competent and sincere. The most noticeable thing about the kids themselves is how uncommonly quiet they are—the effect of sedation.

Things get considerably grimmer inside the “annex,” where problem boys like Michael are housed. No murals relieve its institutional drabness; instead one wall sports a bare Sheetrock patch where a previous resident punched a hole. Sulky-looking teenagers sent by the juvenile courts for psychiatric evaluations wander listlessly about or gaze dully at the television that provides their only diversion. The unit’s two isolation rooms open off the annex’s dayroom. Each isolation room measures about eight feet square. A vinyl-covered mattress and a blanket lie on the floor; otherwise the room is bare save for the convex mirror positioned so that every corner of the room is visible from a narrow window in its door.

The AU doesn’t look like an evil place. It isn’t an evil place. But neither is it a place for autistic children. The unit’s treatment program is designed to help teenage psychotics, who have already developed relatively normal language and social skills. After a few weeks of therapy, augmented by psychotropic drugs, most of them can function well enough to return home. Like most chronically understaffed mental hospitals, the AU relies heavily on medication to keep its inmates in line—it’s a matter of survival. “It’s drug city over there,” one mother complained. “They think they can solve all their problems with drugs.”

Medication does seem to help many psychotics, but with autistics it may do as much harm as good. Dr. Bernard Rimland, a leading researcher on autism, surveyed the parents of two thousand autistic children and found that only 25 per cent thought drugs helped their child. Twenty-nine per cent felt medication made the child worse, and 46 per cent saw little change.

A Better Way

If drugs don’t work, what does? Many experts believe that behavior modification is the answer. Texas’ most intensive behavior modification program is housed in quarters borrowed from a Richardson Presbyterian church. It’s called the Lynne Developmental Center, and its director is Clay Hill. At 31, Hill, a big, shaggy-haired man, looks more like a middle linebacker than a teacher of little children. As he talks about autism, he slowly closes in on his listener, driving home his message subtly but persistently with sheer physical presence. When parents talk about him, improbable words like “miracle” and “saint” keep popping up.

Like others who use “B-mod” (also called operant conditioning) with autistic children, Hill is following in the footsteps of Dr. Ivor Lovaas of UCLA. Lovaas has revolutionized the treatment of autism since the early sixties, building on the psychological theories that originated with Pavlov’s famous experiments on his dog. Practitioners of operant conditioning have little patience with delicate psychoanalytical probing. Forget the inner workings of the mind, they say; just concentrate on changing behavior. In other words: treat the symptom, treat the disease.

To eradicate autistic behaviors, Lovaas subjects the child to an intense, extremely structured set of demands, starting with basics like sitting still and making eye contact. For each appropriate behavior the child receives a “reinforcer,” such as a morsel of food or a hug. Inappropriate behaviors are either ignored—on the theory that to notice them is to reinforce them—or punished with an “aversive,” such as a thunderous shout of “No!” Lovaas and his students see that the child works from morning until night, month after month, until his stims and self-abuse are controlled and he has learned to communicate, either by speech or by sign language. It’s an exhausting process, but with young children it works: half of the preschoolers whom Lovaas treated in a recent study were able to attend a regular kindergarten.

The Lynne Developmental Center plainly evinced the success of Lovaas’s methods. In one room six children sat quietly around a table working their arithmetic as Clay Hill recounted each one’s history in a whisper. “When she came to us a couple of months ago, she didn’t talk. . . . That one used to scream all the time. . . . He’s a real anxious kid, but he’s real bright. . . .” A casual observer could have easily mistaken these children for a group of normal second graders, but Hill put little stock in their academic accomplishments.

“Behavior and language are much more important,” he stressed. “Some of the parents get hung up on academics—the kid can’t tie his shoes, but if he can do long division, it makes the parents feel better. We find some kids who can multiply in their heads but who might not be able to hand you five building blocks if you asked them to.”

“Compliance” class lays the foundations of normal behavior on which all future progress will rest. Here, each exacting, pertinacious teacher drilled two small students on basic commands.

“Ruben? Look at me,” one teacher demanded. “Good looking!” Ruben, an alert, flirtatious three-year-old with the face of an angel, eagerly cocked his head and opened his mouth like a fledgling sparrow for a shot of Coke from a squirt bottle.

“Sterling? Stand up. Good! Sit down. Very good!

“Ruben? Ruben! Okay now, Ruben, pay attention. Where’s your nose? . . . No, not ear, nose. Yes, that’s right. Good boy!

“Sterling? Oh, that’s good looking, Sterling. Yes, I like that. I like it very much!” the teacher cooed, rewarding Sterling with a hug and a quick tickle.

“Ruben! Stop that stim!” she suddenly bellowed, glaring with exaggerated displeasure at the child until his hands ceased twitching. “Stop being silly. It’s time to work. I don’t like that stim. Okay, stand up. . . .”

In the sign language class upstairs, the pace was slightly less frantic. Brian, a well-behaved, dreamy lad, identified objects in sign language at his teacher’s request, smiling slightly as she stroked his face for a job well done. Brian had come to Lynne several months earlier after he nearly killed himself by swallowing inedible objects. Clay Hill’s judicious use of behavior modification soon broke him of the habit. Once Brian’s mother was physically afraid of her son. Today she glows as she speaks of him, tripping over her words in her eagerness to brag about his progress.

Down the hall five or six teenagers were laboriously sorting nuts and bolts in the “prevocational” class. Most of these older kids will never be able to work on their own, but the more competent ones do chores for the local parks department under the supervision of their teacher.

The school day at Lynne begins at nine and ends at four, but for most of the kids that’s only the beginning. Twenty-three of the center’s thirty children also live in one of its teaching homes, where they are taught basic household and grooming skills. From the moment the children walk in the door until they go to bed, they are learning. They get more language training, and they learn to wash their hands, brush their teeth, make their beds, sort and fold the laundry, and set the table. Nothing is left to chance: every task has been broken down into its minutest components (washing hands involves eleven steps). Just as at school, each child’s progress on every step of every twenty-minute lesson is recorded. Hill considers the teaching homes the backbone of his program: the teaching parents earn more than his classroom staff, who are paid on a par with public school teachers.

As Hill conducted a tour of one of the homes, he encountered Ruben, the blond angel of the morning’s compliance class. At home, though, Ruben was no angel—at least not when Hill selected him to demonstrate his accomplishments. Ruben wanted his dinner; he wasn’t used to working at this exact time of day, and he didn’t like it one bit. The child who had been alert, eager, and giggling that morning was transformed in a matter of seconds into a screaming, red-faced bundle of fury. At school, the teacher would have scotched his outburst with a quick shout, but the Department of Human Resources, which licenses the teaching homes, has forbidden the use of aversives in them. So Ruben continued to scream and Hill continued to calmly insist that he sit, stand, look, and gesture as asked. For several minutes the battle of wills raged, the tiny boy and the large man evenly matched in their stubborn determination. Then, just once, Hill raised his voice slightly—nowhere near the levels used in class, but perceptibly. Ruben paused, considering Hill intently. From that point his yells quickly subsided until he was calm enough to perform the simple tasks required of him. With a hug and a ruffling of the child’s blond locks, Hill sent him back to the kitchen. When he peeked in a few minutes later, Ruben was digging into his dinner, but the child managed to pry his attention away long enough to wave a cheerful good-bye.

“A lot of people oppose the use of aversives,” Hill acknowledged, “but the parents know better. You can pretend that everything is peachy-creamy and that you should never punish a kid, but the child won’t benefit.”

Hill feels just as strongly about other parts of his program. For one thing, he uses no psychotropic drugs at Lynne. And like Lovaas, he eases his children into a regular nursery school as soon as possible, to expose them to normal children. His employees also act as consultants to school districts statewide, trying to help the public schools cope with autistic students. And Hill insists that parents participate in their child’s training. Those who live nearby spend one afternoon each week at the center, learning techniques and sharing ideas with the staff. Those who live in other cities are asked to visit for several days before each vacation for a crash course.

Hill’s startling success can create problems, however: parents often want to take their child home too soon. “We made the decision to keep each kid one year longer than seems strictly necessary,” Hill explained, “because once you’ve gotten the behavior under control, you have to pull back gradually. We overteach and we create a totally structured environment, but that’s not a realistic situation. In the end we have to remove some of that structure. Our goal is for the kid to handle everything on his own. Unless we can teach him to internalize the control, all our work goes down the drain.”

Although he’s hailed as a savior by parents and teachers, Hill adamantly denies that he has a cure for autism. “We’re not faith healers,” he insisted. “We only control the symptoms. And we’re still in the pioneering stages. We make mistakes, but we’re learning all the time.”

Frontiers of Care

What Clay Hill is to Dallas, Jim Clark is to Houston. The Bayou City has nothing directly comparable to the Lynne Developmental Center, but many of the same services are provided through a public school program Clark founded and through his current project, Avondale House. Set in a graceful red-brick house on a shady street in the Montrose area, Avondale conducts no formal classes but offers after-school, residential, and weekend care for severely handicapped children, including autistics. Avondale calls itself a family cooperative, and Clark says his program is based on the premise that “the solution lies in the family unit.” Like Clay Hill’s teaching homes, Avondale concentrates on controlling autistic behavior and teaching basic skills.

The program Clark began for HISD in 1972 is considered a model for public schools. Spread throughout the district are four elementary and one secondary “appraisal and treatment” centers for severely rebellious, psychotic, or autistic children. Visiting the elementary programs, one is struck less by classroom techniques—which resemble those at Lynne, minus some of the intensity and the aversives—than by the enthusiasm of the staffs. A kind of can-do attitude prevails: the conviction is that with a structured environment and lots of attention, these children can be helped.

The real showplace of the HISD program is the secondary-level appraisal and treatment center, housed in brand-new Welch Junior High. The center’s three classrooms are built around an office with windows made of one-way glass so that visitors can observe each classroom without entering it. The eight or so teenagers in the “withdrawn” class work puzzles, perform simple counting exercises, and engage in other activities one associates with children less than half their age. For every task successfully completed, the child receives a token redeemable for a favorite food or other treat—a familiar behavior modification technique.

In fact, the center’s familiarity and its high-tech quarters are almost too reassuring. They make it too easy to forget that many of these children will spend the most fruitful years of their lives here. Few employers are anxious to use the vocational skills these kids are struggling to learn. Their autism was caught too late; most of them will end up in institutions, where they are sure to regress.

What the Welch appraisal and treatment center cannot correct, Dr. Kay Lewis of the Texas Research Institute for Mental Sciences (TRIMS) hopes to prevent. In studying the early lives of adult schizophrenics whom she suspected of having been autistic children, Lewis found that many of them had been sickly babies—as Michael Shipley was. Lewis theorized that infants who spend a lot of time in a hospital, in a constantly lighted, noisy room where doctors and nurses are forever sticking them with needles, conclude that human beings bring pain and that the world is not such a great place. So TRIMS got together with the pediatrics department of the University of Texas Medical School at Houston to start an infant stimulation program, letting parents touch and reassure their baby right in the intensive care nursery.

Bringing parents into the nursery accomplishes two things. First, the child begins to form attachments and embark on a normal developmental road. Second, it helps parents overcome the sense of helplessness that might otherwise cause them to withdraw just when their child needs them most.

Although most of the TRIMS budget goes to patient care, the institute also serves as the primary research and training arm of the MHMR system. In practice this means that Lewis ends up giving a lot of support to school districts around the state. A harsh reality confronts every program for autistics, large or small, public or private: there just are not enough trained teachers to go around. And those few burn out at an appalling rate. It takes a very special kind of person to work day after day and week after week with virtually no sign of progress, so good teachers are in tremendous demand. It’s not unknown for one school district to hire away another district’s entire classroom staff. And this situation isn’t likely to improve any time soon—Texas’ universities offer virtually no teacher training in autism.

Why the System Fails

The treatment of autism is moving ahead by leaps and bounds. So why did Michael Shipley die? Why couldn’t the state, with its vast resources, accomplish what the Lynne Developmental Center, HISD, or Avondale House can? Three factors stand out: state institutions are pathetically understaffed; they are caught in a morass of interagency buck passing; and they are by their nature too restrictive for many patients.

MHMR’s facilities can’t keep good direct-care workers—the staff members who work most closely with the patients are severely undertrained and even more severely underpaid. Institutions have become a place of last resort for those who work in them as well as for those who live in them. After a four-day orientation, a direct-care worker at the Austin State Hospital is put to work on a ward with thirty psychotic patients—sometimes all by himself. He is paid $580 a month, which nets him little more than $400. The hospital does require each worker to complete a series of training “modules” during his first six months on the job, but with over 100 per cent annual turnover among workers at this level, the units can hardly build a well-trained direct-care staff. And autistic patients, who so desperately need consistency, must face a constant parade of new faces. Since Michael’s death, two of the AU’s most experienced direct-care workers have taken more lucrative jobs on a Motorola assembly line.

When Michael died, John Douglas was helping train college interns as child-care workers at the CPU. The team that investigated Michael’s death specifically cited the need for better-trained workers at the AU, but Tipton had barred Douglas and his interns from the unit. Funding for the training program dried up entirely at the beginning of this year, and Douglas quit his job with the Austin State Hospital in February.

Staffing is a fairly clear-cut issue, but to understand the politics of autism, one must first hack a path through a thorny tangle of acronyms, legalisms, and jargon: MHMR, TEA (Texas Education Agency), DD (Texas Planning Council for Developmental Disabilities), IEP (the individual education plan prepared for each handicapped student), 94-142 (the federal Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975), and a host of others. The terminology is merely pesky; the reality behind it is catastrophic. What all the letters and numbers, agency acronyms, and legal citations boil down to is this: no single agency is in charge of helping autistic or other handicapped people in Texas. “The problem with the system is that there is no system,” says one seasoned observer. “Each agency does its job, but its job has boundaries, and that’s where the problems arise.”

The lack of interagency coordination has become especially critical since 1975, when a federal law was passed guaranteeing handicapped children the right to a “free appropriate education,” thus greatly increasing the responsibility of the Texas Education Agency. Just what constitutes an “appropriate” education, has yet to be established, and until the issue is clarified by the courts, parents who think their school district is not meeting its obligation must haggle with a TEA bureaucracy that habitually avoids action until its back is against the wall. For example, TEA has nominal responsibility for seeing that MHMR provides children in its facilities with an education equal in scope, if not in kind, to the education children receive in regular public schools. In fact, though, MHMR, which is its own school district (although it has no taxing authority), spends only half as much per pupil as the average public district. Nevertheless, TEA has not confronted MHMR on the issue, and the very children who need more intensive education receive less. “The lack of coordination and cooperation is absolutely appalling,” says Dayle Bebee. “It’s as if there were a moat around each agency, and never the twain shall meet.”

For the past decade, the national trend in mental health care has been toward community-based services and away from institutions. Texas, however, still institutionalizes 84 per cent of the people who receive mental health services. That puts us well below the national average, and even farther from leaders like Montana (only 43 per cent institutionalized). Despite MHMR’s theoretical commitment to “normalization” and treating people in the “least restrictive setting,” as the law requires, for 1980 the Legislature appropriated only $46 million for community services versus $160 million for state schools and $124 million for state hospitals. The community programs that do exist cater to the mildly handicapped, so most autistic adults—thousands of them—live in institutions where they are classified as retarded or psychotic.

The institutions continue to prosper for the simple reason that they have strong support within both the department and the Legislature. MHMR’s board, caught between the administrators, who control the flow of information, and the lawmakers, who control the flow of cash, has been hard pressed to effect even the basic changes mandated by its own policies and by law. Most observers give MHMR fairly high marks for trying to do its job and reserve special praise for Commissioner James Kavanagh, whom they credit with making sincere efforts at reform in the face of considerable odds.

Still, the scandals persist. For years liberal reformers have railed against overcrowding, inadequate care, and multifarious abuses in both the state hospitals and the state schools. The past decade alone spawned a plethora of investigations, including internal MHMR reports, legislative hearings, governor’s task forces, and independent studies. Charges of abuse and neglect, some involving deaths, have racked the Rusk, Terrell, and Austin state hospitals, as well as the Austin, Denton, Fort Worth, Mexia, and Richmond state schools. Every few years some grisly report comes to light, and the department promulgates new regulations and prays that no other incidents will surface. But one always does. For example, at the very time Michael’s parents wanted to place him in the Richmond State School, a report was being prepared concerning abuse and neglect of several residents there, two of whom died. One woman was bitten repeatedly by other residents, and a child lost the sight in his one good eye.

Despite horror stories like these, many parents cling to the institutions. MHMR personnel have preyed upon parents’ fears by insinuating that if community-care advocates have their way, all the institutions will be shut down overnight and a bus will deliver the inmates to their families’ doorsteps. And lurking in the back of every parent’s mind is the question of who will provide for his child after he is gone. One mother, who had removed her son from an institution because she felt he was being neglected, vowed that he would go back only “over my dead body,” then added plaintively, “I only hope he dies before I do.”

In view of the current dearth of established, high-quality community programs, parents’ fears are well grounded. The shining ideal of deinstitutionalization often hides an ugly reality of harassment and exploitation. Retarded and mentally ill patients have been discharged into the community with pitifully little money, no job prospects, few friends, and wholly inadequate survival skills. MHMR follow-up workers assigned to help these people tell sobering tales about their clients, who receive only $208.20 a month in Social Security income. Many end up in filthy, broken-down boardinghouses where they are abused by the proprietors or other residents; they wander the streets all day; they cannot manage even the most basic aspects of their lives, like taking their medication or handling money. Private nursing homes licensed to care for the retarded often exclude severe cases because of their problem behaviors. Besides, a nursing home is worse than an institution in one respect: it provides even less education. Faced with poverty, exploitation, loneliness, and indifference, many former inmates simply give up and return to the institution.

Sadly, many of them could function in the community if they could live in supervised group homes and work in sheltered workshops. “Many of these people could walk out of here tomorrow if only the services existed,” says Dr. Melodie Clemons, creator of a new Multiple Disabilities Unit at the Austin State Hospital. Clemons started the unit to care for people like Michael Shipley, who might well have been transferred there had he lived. The unit will be better funded and better staffed than other adult units, but Clemons acknowledges that it cannot offer the kind of care given by small teaching homes like Clay Hill’s, which she sees as the best solution.

One of the strongest arguments marshaled by community-care advocates is that autistics and other mentally handicapped people can be cared for more cost-effectively in their own neighborhoods than in large colonies far from home. It costs about $80 a day to house a person at the Adolescent Unit compared to $25 a day for a residential student at the Lynne Developmental Center. In contrast, the direct-care staff—the people who spend the most time with the children—are paid about twice as much at Lynne as at the state hospital.

In the final analysis, however, we cannot blame the institutional staffs, the agency bureaucracies, or even their boards. To agitate for overnight change would be naive: it is not in the nature of bureaucracies to gladly allow themselves to be dismantled—no matter what they may believe is the best way to care for people. And it is not in the nature of agencies to look with favor on private contractors who come to them with their hands out asking for the agency’s money. And why should they? The taxpayers of Texas built the institutions in the first place, conveying the tacit message that these mentally handicapped people are different from the rest of us, that it’s okay to treat them differently. The real problem, says Dave Sloane of Advocacy, Inc., is that “the agencies haven’t shown enough anger and resentment. They’ve not been aggressive enough in laying the responsibility where it belongs—with the public and its elected officials.”

Fighting for Change

These days MHMR finds itself besieged on all sides. Even the governor has taken a hand, telling all state agencies to cut their staffs by 5 per cent. Faced with his mandate, the MHMR board replied that it had no intention of cutting staff if the cuts would jeopardize the accreditation that allows its programs to dip into the lucrative federal cookie jar. Under pressure from Clements, the ranks are being pruned, however, arousing widespread apprehension that the quality of care in MHMR facilities will suffer.

The department is currently under attack in the courts as well. Armed with an abundance of new federal and state laws guaranteeing the rights of the handicapped, some advocates have sallied forth on ambitious class-action lawsuits on behalf of residents in state institutions. The suits have bogged down in the courts, though, stymied by MHMR’s delaying tactics. Pitted against the considerable legal resources of the state, Dallas Legal Services, the firm handling the suits, can barely keep up with the evidence—which now fills ten filing cabinets—much less press the cases to trial. When and if the cases are settled they could bring widespread reforms, but that day seems a long way off.

Meanwhile, the MHMR task force on autism and the Texas Society for Autistic Citizens are gearing up for the next session of the Legislature, working to get appropriations for autism included in MHMR’s budget. Insiders at the agency and the Capitol give the advocates at least a fighting chance, but their ultimate success will depend largely on the good faith of the MHMR bureaucracy. In addition to wrangling with the agency and the Legislative Budget Board, TSAC is casting its lot with the Texas Committee of Organizations for the Handicapped (TCOH), a broad-based coalition that operates on the theory that what one organization can’t accomplish on its own, many together may. TCOH is mapping strategies for the session, including a plan to review and evaluate each piece of legislation relating to the handicapped.

TSAC’s Twombly, for one, is also pushing for the formation of political action committees to drum up campaign contributions and for grass-roots organizing. Some 982,000 Texans suffer from handicaps, and Twombly dreams of melding them into a potent political force. He admits, however, that at present that prospect looks dim.

So, for now, TSAC is working hand in glove with the autism task force, hoping by force of argument and the specter of Michael Shipley to make the MHMR board and the lawmakers see things their way. “The traditional method is to make your mistakes the first time around and go back a second time armed with what you’ve learned,” Twombly acknowledges. “But this time we’re going for broke.”

Late in February the Shipleys made their peace with MHMR, accepting $75,000 and releasing the state from all further liability. At one point the lawyers had contemplated tying strings to the settlement to force MHMR to make various procedural changes. In the end, though, the family needed the money too badly to wait.

Commissioner Kavanagh has promised that he will continue to work with TSAC and Advocacy, Inc., to correct the problems that led to Michael’s death. He says he will soon unveil a more stringent drug policy designed to safeguard against overmedication. He has not placed the AU and the CPU under one director as the investigating committee urged, but the AU’s new director once interned at the CPU, so relations between the two units are expected to be cordial. Kavanagh also has told the Adolescent Unit to hire more direct-care staff. These days the department and the advocates are singing each other’s praises, riding a wave of outward goodwill and cautious optimism in high hopes of sweeping the public and the Legislature along with them.

However, in January, just six months after Michael died, Advocacy, Inc., got a call from a woman whose daughter lived at the Adolescent Unit. The woman had never heard of Michael Shipley, but she was concerned for her daughter. Her reasons? The doctor refused to answer her calls or to discuss medication or other treatment plans with her; the staff reacted hostilely to her questions; they granted her access to the unit, then suddenly revoked it and would not tell her why; they seemed to expect her severely disabled child to function at a much higher level than the girl was capable of. Much to the woman’s dismay, the new director proved to be no more responsive to her questions than other AU employees. The child has since been discharged, but Dayle Bebee brought the complaint to Kavanagh’s attention, and another investigation is under way.

- More About:

- Health

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Richardson

- Houston

- Austin