This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Ed Bass, billionaire bachelor, urban developer, and self-styled ecopreneur, describes the brave new world he is building, pests and all. “Termites break down range grass and cycle it back into the soil of tropical savannahs,” he says in a soft yet assertive voice, explaining why the insects will be enclosed in Biosphere II, a two-and-a-half-acre version of Earth under construction in the Arizona desert. Of course, as befits a man intent on building a better, if not bigger, world, Bass’s termites will be less destructive than their lumber-loving counterparts. “We had to find a species that doesn’t like to eat silicone caulking,” he notes, mindful of the seal that will protect his world from the real one. “So we ran an experiment we called the termite taste test, tempting the critters with sealant sandwiches.”

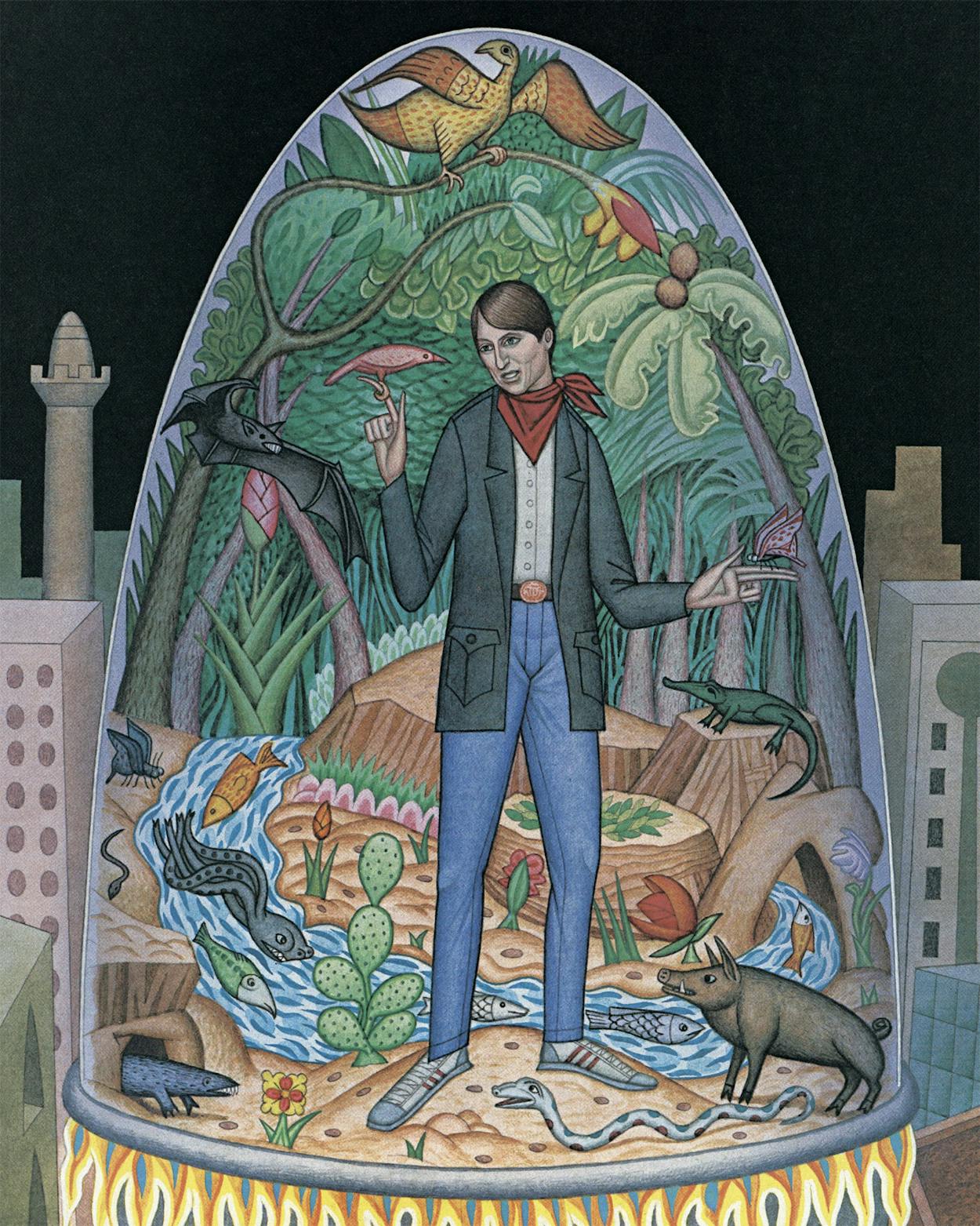

On New Year’s Eve in downtown Fort Worth, Ed Bass stands at the bar of the Caravan of Dreams jazz club in the avant-garde performing arts center that is another one of his creations. He is ever gracious to a steady stream of well-wishers, oblivious to the mellow bleats of saxophonist Kirk Whalum performing in the background. But his gaze goes rapt—punctuated by rapid blinking—when he talks about Biosphere II—the giant vivarium that he is financing at SunSpace Ranch in Arizona’s Canyon del Oro—a phantasmagoric latticelike structure that, if successful, will sustain the lives of eight humans, or “biospherians,” who will be hermetically sealed inside the sphere for two years in the fall of 1990. Along with the eight people and the termites, Biosphere II will contain some 250 other species of insects, as well as boojum trees, banana plants, hummingbirds, African goats, a family of Vietnamese pigs, and a colony of mosquitoes. “Luckily, we’ve found a certain type of mosquito that bites frogs, not people,” Bass says, a grin revealing dimples below his round, rosy cheeks.

Other men dream of creating the perfect world. Edward Perry Bass, 43, has the vision—and the cash—to make it happen. In the not-too-distant past he was labeled the eccentric Bass brother, the oddball who performed in experimental theater and hiked in Nepal while his brothers—Sid, Robert, and Lee—stormed Wall Street as they busily converted the family’s millions to billions.

Today Ed Bass is a strikingly handsome, self-assured gentleman with the knobby Bass nose, his prematurely graying hair curling stylishly over the collar of his blue Western-cut jacket. Trained as an actor, Bass has mastered a number of roles. As a scholar, he heads a think tank that studies the interaction between the world’s ecology and man’s technology. His pressed jeans and red bandanna give him the look of a rancher, which he also happens to be six months a year, tending to a half-million-acre cattle station in the Australian outback. When he dons a navy-blue suit and makes a pitch for tax breaks so that he can build the first inner-city housing in Fort Worth in decades, he is the visionary investor. The fact that much of Bass’s assistance and inspiration comes from a group of artists and technicians he befriended in New Mexico almost twenty years ago makes him one of the few practitioners of a managerial style best described as tribal capitalism. And as a hometown boy, he participates in the Fort Worth rodeo parade, yee-hawing to the crowd from atop a horse leading the Caravan of Dreams float. “One thing my travels have given me is an understanding of culture and an appreciation of culture,” Bass says without irony.

Although his path to glory has been less conventional than his brothers’, Ed Bass may ultimately be no less successful. Ten years of wandering in the desert—sometimes literally—have finally led him to reclaim the legacy that once lay so uneasily on his shoulders and to embark on projects that may be both more dramatic and more lucrative than any venture so far associated with the Bass name. Through it all, Ed has remained true to his ideals. As one Bass brothers associate puts it, looking back over tougher times, “Ed was just ahead of everyone else, that’s all.”

The Legacy

“My father is such a remarkable man, it took the four of us to emulate all his diverse qualities and interests,” Ed Bass says. But as inspiring as patriarch Perry Bass may have been, the man who served as the role model for Ed Bass was Perry’s uncle, Sid Williams Richardson. The brother of Ed’s grandmother, Annie Cecilia Richardson, Sid was the second of four children whose father was a farmer and orchard manager near Athens. Early on, Annie demonstrated the family gift for spotting shrewd investments: She lent Sid $40 in walking-around money when he told her he wanted to go look for oil in West Texas. “Everybody’s looking for oil in East Texas” was his explanation—and the kind of thinking that turned him into Fort Worth’s first billionaire.

Richardson fit right in with the boomtown that was Fort Worth in 1925. A rough cob with a nose like the trunk of a gnarled oak, he set up shop at the Westbrook Hotel, doing business from a pay phone and renting a cot in the lobby for $5 a night. He knew the risks of his line of work; he had already made and lost a couple of fortunes with his hometown friend Clint Murchison. But Richardson quit worrying about his next meal when he drilled 385 wells in the unexplored Keystone Field near Odessa and struck oil in all but 17 holes. Oil reserves made him rich beyond comprehension; in 1957 he was the richest man in America, according to Fortune magazine. With his best friend and poker-playing pal, Amon Carter, Richardson became a power broker in Fort Worth and the nation. He was even instrumental in persuading Dwight Eisenhower to run for president.

In 1935 Richardson, a bachelor, rewarded his sister’s investment by entering into a partnership with his nephew and only male heir, Perry Bass. The son of Annie and a Wichita Falls doctor, Perry had the benefit of an education at Yale. He had intended to go to law school at the University of Texas; instead he stuck with his uncle and learned the oil business from the ground up. When he wasn’t traveling to prospective drilling sites, he shared Richardson’s three-room apartment at the Fort Worth Club.

Perry moved out when his bride, Nancy Lee Muse, gave birth to their first son, Sid, in 1942. The couple’s four children grew up behind the imposing gates of the family mansion in Old Westover Hills, an exclusive west-side neighborhood in Fort Worth that harbors more millionaires per acre than any enclave in Texas. It was a sheltered upbringing (when Ed wanted to go horseback riding at one of the family ranches, there was always someone present to saddle the horse and help the boy mount), but Perry and Nancy Lee’s boys attended public elementary and junior high schools just like everyone else.

In keeping with Perry and Nancy Lee’s desire to expose their sons to the wider world, they sent Sid, Ed, and Robert to prep school in the East. (Lee, the youngest, went to Country Day School, a private school in Fort Worth that Perry was instrumental in founding). A month before Sid Richardson died in the fall of 1959, Ed enrolled at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts. If Ed’s fortune had made him feel like an outsider in Fort Worth, he remained one at Andover, but for a different reason. Although Ed was studying alongside his social and economic peers, he found it a challenge to adjust to the school’s rigid academic standards and its even more constraining semi-military regimen. His best grades were in biology and mathematics, and his passion was jazz (“We used to play a lot of Ornette Coleman,” Ed, a co-founder of the Andover jazz club, says, “because he was the farthest-out thing we could find”). But his most exciting discovery was art. His mentor was Boston-area photographer Gordon “Diz” Bensley, whose studio art class introduced students to the basic concepts of composition and design. Bensley’s students were directed to hit the streets of Andover, 35-millimeter cameras in hand. “We had assignments to shoot things like a sensuous surface and a syncopated series,” Bass remembers fondly. “Diz Bensley really was the one who got me interested in architecture.” Recalling Ed Bass’s idealism, a family friend says, “Instead of wanting to build a beaux-arts mansion or a modern skyscraper, Ed was interested in building the perfect public-housing project.”

After finishing his undergraduate studies at Yale, Ed served a stint in the Coast Guard, then returned to Yale’s graduate school of architecture, teaching at Andover for two months one summer. His education was cut short, however, when he traveled to New Mexico with a group of friends during spring break in 1970.

In the tradition of D. H. Lawrence, Georgia O’Keeffe, Robert Oppenheimer, and countless other artists, intellectuals, and cultural misfits, Ed fell in love with the state’s rugged landscape and its people’s tolerant attitudes. He settled in Cedar Crest, in the mountains northeast of Albuquerque, where he designed and built adobe structures, dabbled in pottery, and sold Indian jewelry and handicrafts through his Spirit Line Trading Company. In 1974 he relocated to Santa Fe, a mecca for both the jet set and the spiritually inclined.

When he set out in search of some handmade furniture for a house he was building, he met a group of artisans who not only sold him tables and chairs but also persuaded him to join them in designing a new civilization.

The Art of the Possible

The furniture-makers Ed Bass found lived among an eclectic group of writers, actors, engineers, and counterculture brainiacs at Synergia Ranch, fifteen miles south of Santa Fe. The ranch was named in honor of Buckminster Fuller’s concept of synergy, wherein the behavior of a whole cannot be predicted by the behavior of its parts. Besides making furniture, the various parts of this whole made pots, studied ecology, worked construction jobs, performed theatrical pieces under a geodesic dome covered with yellow canvas, and occasionally toured the country in a refurbished school bus, billing themselves as the Theater of All Possibilities.

Compared with the other communes around Santa Fe, like Morning Star and New Buffalo, the Synergia Ranch was downright corporate. The emphasis was on self-reliance. Everyone worked to pay his own way. Drugs were forbidden, new recruits were discouraged, and half the 25 or so residents were Ivy Leaguers. The person who attracted them was a charismatic poet, scholar, and metallurgist named John Polk Allen, whose third wife, Marie, owned the ranch. Allen encouraged activities ranging from experiments in “biodynamic gardening” to recitations of Sufi stories to perfecting the techniques of candle-selling as a means of self-sufficiency—all of which tied into the premise that unless they found some way to reconcile Earth’s ecology with man’s technical innovations, the planet was in trouble.

The ranch hands called their study ecotechnics. Every evening after chores, they met in a dining commons, where one wall was adorned with “e=mc2” and another with an inscrutable mantra, “The Inexhaustibility of Phenomena.” Completing the scene was Allen, who presented his cosmic theories.

A barrel-chested, rubber-faced combination of Walt Whitman, Wernher von Braun, Knute Rockne, and Shemp Howard, Allen recounted his experiences as an Oklahoma farm boy, a labor organizer, and a student at Stanford, the Colorado School of Mines, and Harvard Business School, as well as his work as a metallurgist and executive for David Lilienthal, the first chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission. His discourses meandered from the teachings of the Buddhist canon to his travels with the remnants of the beat generation in Tangier and his meditation on the sight of copulating monkeys in the shadow of the Taj Mahal. He reflected on the second law of thermodynamics and Buckminster Fuller’s “spaceship Earth.” Allen also discussed an array of ideas that included building a ship and sailing it to Australia, constructing a biosphere on Earth, and ultimately colonizing Mars.

Such eclecticism was a siren’s call to Ed Bass. He became a regular visitor to the Synergia Ranch and participated in drama workshops. In keeping with the theatrical nature of the place he, like everyone else, took a nickname—“Sharkey.” Allen called himself Johnny Dolphin. Marie Allen was known as Flash; Kathelin Hoffman, a cofounder of the Theater of All Possibilities, was known alternately as Salty or Honey. Others went by Houlihan, Holerat, and Horseshit.

Bass became further involved when he hired a construction company called Synergetic Operations Corporation (SYNOPCO), run by several ranch residents, to build Llano Compound, thirty semi-detached adobe condominiums on a four-and-a-half-acre lot on Palace Avenue, nine blocks from the Plaza in Santa Fe. The four-year project introduced Bass to a unique approach to management, a system based on the notion of “willing incompetence,” i.e., if you have the drive, you can learn. SYNOPCO hired unskilled hippie laborers and ostensibly turned them into specialists; local craftsmen were brought in to provide on-the-job training. Workers were rotated from job to job, plastering adobe one day, raising frames or pouring foundations the next. A four-hour-a-day, four-day workweek was observed, with five-minute breaks each hour. Women constituted half the work force.

Working with these self-starters validated Bass’s worldview. In much the same way his brother Sid was imposing his particular vision on the American economy, Ed began applying a portion of his share of the family fortune to further his unconventional beliefs.

By the time Llano Compound was finished in 1978, Bass had become a director of something called the Institute of Ecotechnics, which Allen, Hoffman, and other Synergia veterans had founded in 1972. Bass also became the chief financial officer of Decisions Team Ltd., or DTL, a Hong Kong–chartered vehicle for developing and managing far-flung projects, several of which were inspired by the institute. He also created Fine Line, Inc., to fund a variety of ventures.

For tired trekkers Bass built the Hotel Vajra in Kathmandu, Nepal. He acquired Les Marronniers, an eighteenth-century estate near Aix-en-Provence in France that became a conference center and experimental agricultural facility. Through another corporate entity, Bass became a principal investor in a Puerto Rican rain forest, now preserved for study. An art gallery and cultural events center opened in London. In the remote Kimberley region of Australia, Bass set up an experimental grass-seed farm called Birdwood Downs and a cattle ranch, Quanbun Downs, to study grazing in the tropical savannah. There among the jackeroos and wallabies, 30 miles from the nearest pub and 1,200 miles from Perth, the nearest city of consequence, Ed was content. “Distance,” he says, “is a remarkable filter.”

Back at the Fort

Even as he dug postholes in the outback along the banks of the Fitzroy River, Ed kept up with the maneuverings of his brother Sid. As impressed as he was with Sid’s considerable business acumen—his cunning investment in Marathon Oil, his convertible arbitrage deals, his purchase of 5 to 36 percent of the stock of seventeen companies in just two years—what most captured Ed’s imagination was Sid’s leadership in the revitalization of downtown Fort Worth. Charles Tandy, the leather-goods merchant turned Radio Shack tycoon, had erected twin office towers and an inner-city shopping mall before he died suddenly of a heart attack in 1978. Sid finished Tandy’s 12-story hotel, now known as the Worthington. Then he presided over a beautification project for Main Street and embarked on his own agenda, complementing the hotel with the 32-story City Center I and 38-story City Center II office towers—the tallest buildings in Fort Worth—and with Sundance Square, a collection of boutiques, bars, and restaurants that then covered two and a half blocks of restored turn-of-the-century storefronts. They were the kinds of projects that spoke to Ed’s better-world ambitions.

In 1979 Ed moved back to Fort Worth, taking up residence at the Blackstone Hotel, where Sid Richardson had once lived. Three years later Ed decided to add his own stamp to the Bass brothers’ revitalization efforts. He bought a row of three adjacent storefronts on Houston Street and remodeled them into several apartments and an all-purpose arts center that included a nightclub and restaurant and a theater to serve as home base for the Theater of All Possibilities. Topping the building was a 32-foot-high neon-decorated geodesic dome housing cacti and succulents from four desert regions. The complex was named the Caravan of Dreams, and to Bass it symbolized the rekindling of life in a desolate urban environment, which pretty much summarized the state of downtown Fort Worth at the time.

Kathelin Hoffman and other performers set out to meet their local art counterparts. Maybe it was Fort Worth’s long-standing self-consciousness colliding with Allen’s you-are-what-you-want-to-be philosophy—for whatever reason, the two sides did not hit it off. A dance critic was unnerved when a Caravan public relations officer, Jane Pointer, a.k.a. Harlequin or Boogie, displayed a limited knowledge of the dance world. Similarly, a Fort Worth commercial filmmaker was not convinced that Marie “Flash” Allen was a cinema expert. Some local architects looked skeptically at Margret Augustine, the architect of the Caravan of Dreams, whose only architectural degree was from the Institute of Ecotechnics.

It was no surprise, then, that the grand opening of the Caravan of Dreams in September 1983 was a classic study of cultures clashing. The elaborately costumed Caravan collection of actors, gypsies, and ecotechnicians (Ed wore a neon bowtie) puzzled the tuxedoed crowd that included Bass family members, socialites, and business leaders. Equally baffling were the Caravan associate who rode a horse all the way from Santa Fe and the contributions of featured artist Ornette Coleman, who came home to perform a quirky, free-form composition called “Skies of America” with the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra and a piece for string quartet and percussion titled “Prime Design,” which he dedicated to Buckminster Fuller. At the end of the weekend’s festivities, John Allen ushered Coleman and Ed to the podium and raised their hands like victorious prizefighters. The two men exemplified what he and his associates hoped to accomplish in Fort Worth, Allen said; they would “bring together the city’s disparate racial, cultural, and creative elements.” His accolades were premature.

Suspicions about the goings-on at the Caravan of Dreams grew. “Every time they would leave the building, people on the street would turn their heads and stare,” remarked one Fort Worth resident who frequented the Caravan. Not only were they strange, but they didn’t seem businesslike, a bad sign to downtown boosters. Allen, for instance, chanted Tibetan mantras in the Caravan’s restaurant. The first nightclub manager paid more attention to martial arts instruction than to the facility. Some serious theatergoers felt insulted by original dramas like Kabuki Blues, a parable about a group of actors and dancers forced to abandon New York by the evil money-makers of Western civilization. They flee to Australia, where they make a deal with supertechs who provide them with a spaceship. Then they travel to Mars, where they peer through a telescope and watch a nuclear holocaust consume Earth. “It stumbles on a simple rule of theater: entertainment,” a reviewer for the Dallas Morning News wrote. “It’s the play—not the audience—that has missed the mark.”

If the public was puzzled by the plays, it was absolutely flummoxed when Bass, Allen, and other officials of the Institute of Ecotechnics introduced their next project late in 1984. It is Allen’s not-so-unusual belief that the world will inevitably perish, but he does not feel that we are pressed for time. He believes that the human race has 300 million to 5 billion years left and that the only way for mankind to “achieve cosmic immortality” is for humans to create biospheres as “space seeds” and to colonize planets like Mars.

Hence the creation of Space Biospheres Ventures, a corporation formed with the goal of colonizing the red planet. The first step would be the construction of Biosphere II (Earth being Biosphere I), a habitat dreamed up by two visionary architects, Margret “Firefly” Augustine and Phillip “T.C.” Hawes. Biosphere II would be a portable Earth, a suitable habitation for colonizing another planet. But before anyone could set his sights on Mars, there was a public relations crisis on Earth to contend with.

Space Cadets Invade Cowtown

“Edward Bass Funds ‘Intellectual Cult,’ Ex-Members Say,” the front page of the Dallas Morning News screamed on March 30, 1985. Articles in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram and the Washington Post followed, all essentially instigated by Carol Line, the Caravan’s assistant to the artistic director. Line had been charged in December 1984 with stealing from $750 to $20,000 from her employers; she had signed a confession and, later, a promissory note agreeing to repay more than $23,000. In January Line, who had a background in journalism, started collecting information after T-Bone Burnett, a Fort Worth musician and record producer, told her that he worked with a group called the Spiritual Counterfeiters League and that in his opinion the Caravan was controlled by a cult. With Burnett’s help, Line went to Sid Bass and Bass family security chief Joel Glenn, who she said had planned to separate Ed from John Allen with the help of a deprogrammer by the end of May.

Carol Line started talking to reporters in March. The result was a string of stories that branded the group at the Caravan of Dreams as elitist and that claimed the group practiced mental torture. The Dallas Morning News story portrayed Ed Bass on his hands and knees, denouncing his brothers—and presumably himself—as capitalists. Quoting Line, the Fort Worth Star-Telegram reported that Allen verbally and physically abused Bass in acting class: “ ‘It was screaming, punctuated with kicks and slaps,’ she said.” The Washington Post reported that “Allen said the alleged beating incident was a fabrication by Line. He added that he had never struck Bass and had yelled at him only ‘when he was acting like a snotty Yale millionaire.’ ”

Ed and his family vigorously denied the charges. Despite their distaste for publicity, Sid and Robert issued statements of support for their brother. Ed telephoned reporters from Australia to dismiss the accusations as balderdash, while in a prepared statement he stuck to his guns, stating, “I am certain that time will demonstrate the value and validity of . . . combining sound traditional principles with an innovative capitalist approach.”

By mid-May Line, quoting the old song “You Always Hurt the One You Love,” had issued public statements apologizing for her earlier remarks and recanting her accusations, which prompted some reporters to print retractions. Line repaid $5,000 of the money she owed her employer and in the summer of 1985 went back to work at the Caravan. The charges against Line were dropped in September 1986, and the Caravan terminated her employment in January 1987. Line, who now manages a rock group in Austin, stands by her original story. Ed Bass remains stoically silent about the incident.

The brouhaha did have the positive effect of persuading many of those involved with the Caravan to get their act together. Gregg “Chutney” Dugan, a former Synergia Ranch resident, was brought in as the general manager of the Caravan. “The place needed a hierarchy,” says Dugan, who had faced down Yemeni patrol boats in the Red Sea in his previous role as the captain of the R/V Heraclitus, a ferro-cement Chinese junk operated by DTL. Thanks to Dugan’s organizational skills, the Caravan of Dreams nightclub ranks as one of the premier jazz venues in the United States. Kathelin Hoffman started a record label bearing the Caravan name; it sports an impressive roster, including beat author William Burroughs, Ornette Coleman, and Dallas trumpet prodigy Roy Hargrove—even poet Johnny Dolphin. The Theater of All Possibilities, now the Caravan of Dreams theater company, has earned its spurs too, attracting a core group of theatergoers to ambitious productions including Oresteia and Japanese No plays.

Even Allen has rejoined the mainstream. When he makes a presentation before Fort Worth’s establishment, he wears a double-breasted jacket and a conservative red tie. His topic, however, has not changed. “Here is how things will look when you come in from the surface of Mars,” Allen says, showing slides that detail the profit potential of Biosphere II.

But Allen isn’t making a sales pitch. With Ed Bass backing the project to the tune of $30 million, additional funding is not required. Many patents are already pending, and the involvement of Carl Hodges, the head of the University of Arizona’s Environmental Research Laboratory and the designer of the Land Pavilion at Walt Disney World’s Epcot Center, has added credibility to the project.

Space Biospheres Ventures is poised to exploit the tourism angle too. Allen Boorstein, the marketing whiz behind Snoopy, Roy Rogers, and Cabbage Patch dolls, has been hired to peddle the Biosphere II image. And all this is in addition to the income anticipated by the construction of Biospheres III, IV, and so on, for installation on Mars and elsewhere. “Small biospheres would make good health clubs on top of buildings in New York too,” Allen says.

The actual site of Biosphere II, thirty miles from Tucson, can make visitors feel as if they had wandered into the Garden of Eden. In a greenhouse where plants are being cultivated, big clumps of ripening tomatoes flourish as carplike Tilapia fish swim between tender green shoots of rice in three-foot-tall rectangular fish ponds. Little white signs mark yard-square “fields” of wheat, rye, and alfalfa.

Framed by heavy machinery and a battalion of construction workers, the site with its sunlit, vaulted spaces held together with lattice tubing could easily be mistaken for a future Hyatt Regency or a massive Christo environmental-art project. But instead of swimming pools, hotel rooms, or art for art’s sake, there will be seven biomes, each one representing an ecological province: a savannah, a marsh, a 25-foot-deep ocean, a desert, a tropical rain forest complete with an 80-foot mountain, a farm, and a city—the living quarters for the eight biospherians who will be locked inside.

The new world is here, just as Ed Bass dreamed it. Trained in emergency dental techniques by U.S. Navy instructors and in interpersonal dynamics by Kathelin Hoffman, the biospherians will spend their days gardening, swimming, and performing dozens of experiments to monitor the interaction between plants and animals. Their only link to the outside world will be telephone, computer, and video communication. Although Bass decided not to be a candidate for enclosure, he envies those who will be chosen. “They will be able to lead a much richer life than most people,” he says.

Citizen Ed

On an April morning, Ed Bass calls a press conference at the Caravan of Dreams. Standing comfortably at the podium, he unveils plans for Sundance West, a $25 million, twelve-story high rise with apartments, movie theaters, and shops, the first downtown housing to be built in more than two decades. The press conference dovetails neatly with the following day’s international symposium, “The Art of Future Cities,” at the Caravan, that will kick off the Main Street Fort Worth Arts Festival. The mayor, the chamber of commerce, and representatives of Downtown Fort Worth, Inc., are on hand, along with a battery of reporters, photographers, and television cameras. Ed Bass is the center of attention.

The aviator glasses, spiked haircut, and ascots he once favored are gone. His costume for the press conference is instead a conservative gray Savile Row suit, a blue-and-red power tie, and the same Ivy League haircut as his brothers have. But Bass has added a shiny belt buckle with the Sundance West logo, a depiction of the Charles Russell painting Smoking Up, which his father happens to own.

The conference affirms the arrival of Citizen Ed, the Bass brother who sits on the boards of everything from the Australian Pastoralist and Graziers Association to the New York Botanical Garden and the Fort Worth Chamber of Commerce. He is the proud founder of the Philecology Trust, which underwrites nonprofit ecological ventures.

Over the next two days, as he describes an improved downtown landscape that will include Sundance West, Ed Bass reveals his passions and priorities anew. He offers a critical analysis of brother Sid’s projects, citing, among other faults, the skyway linking the two City Center office towers—it keeps people inside their buildings instead of turning them loose on the street. He comes very close to boasting about the risk involved in building Sundance West (“I don’t think you’ll find Trammell Crow rushing into downtown Fort Worth residential,” he jokes). And for all his fine breeding, he slides into a Texas drawl when he pronounces “Woolworth’s” as “Woolsworth’s” during an informal tour of the Sundance West site. Walking toward the old Edison building, which will be cleared for underground and street-level parking, Bass even admits dismay about that element of downtown revitalization. “A city full of parking lots,” he says, “is like an old mouth with missing teeth. It can’t chew very well for all the empty spaces.”

After a chance meeting with conference guest, sociologist, and urban planner William Whyte at the corner of Second and Main, Ed Bass heads back to his office. His stride is not the usual captain-of-industry strut common among other men going in and out of the building. Instead, Ed Bass walks with an exuberant bounce, taking in the street scene around him.

Sid Richardson punched holes in the alkaline soil of West Texas while everyone else rooted around for oil in East Texas. Ed searches for financial opportunity and a better life by reviving devastated urban landscapes on Earth while creating closed environments for outer space. Like Richardson, Ed has made his own way. Like his brothers, he hedges his bets, crap-shooting no more than 10 percent of his capital and keeping the balance in conservative, conventional investments. Yet Biosphere II is such a fantastic long shot that even if he is half-right, Bass stands to gain through patents and technological breakthroughs far more riches than any of his brothers, his father, or Sid Richardson. And as Bass figures it, “Regardless of what we find in this initial major two-year experiment, there will be tremendous accomplishments. We’ll learn how these systems work, how to build them, and how to operate them.”

Before he reaches the escalator entrance to City Center I, Ed Bass pauses one last time, his feet planted firmly on the pavement of the city he loves, his head tilted skyward, gazing beyond the towering buildings toward the heavens, maybe even toward Mars. After twenty years Ed Bass is finally on center stage, in the role he was born to play.

Bill Crawford is a radio producer living in Austin.

- More About:

- Business

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Fort Worth